Authors

Content

Foreword

Rt Hon Lord Campbell of Pittenweem CH CBE KC, former Leader of the Liberal Democrats

Rt Hon Sir Michael Fallon KCB, former Secretary of State for Defence

Alicia Kearns MP, Chair of the Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee

General Lord Richards of Herstmonceux GCB, CBE, DSO, DL, former Chief of Defence Staff

Rt Hon Lord Robertson of Port Ellen KT, GCMG, former Nato Secretary-General and former Secretary of State for Defence

Lord Sedwill GCMG, former National Security Adviser and Cabinet Secretary

In an era of growing polarisation, it is fascinating to witness a multi party consensus on Iran policy. Iran’s increasingly appalling human rights record, accelerating nuclear programme, sponsorship of proxies throughout the Middle East, extensive assistance to Russia in its brutal war on Ukraine, and sponsorship of terrorism and kidnapping makes it an obvious threat to international stability.

Iran poses a threat to British citizens on British soil. MI5 Director Ken McCallum identified no fewer than ten credible Iranian plots on British soil in 2022, while Met counterterrorism policing lead Matt Jukes identified another five plots in early 2023. Undoubtedly, Iran is becoming more brazen in its prosecution of international disruption.

In such a critical geopolitical environment, we are proud to endorse this paper on British strategy towards Iran. It is truly the first of its kind: no British think-tank has written such a comprehensive analysis of the Iran threat, and provided detailed recommendations that cut across policy areas with such specificity and nuance.

The policy the paper articulates will make the UK a critical power in an increasingly fractious Eurasian political environment. Russia’s acute military threat is the most obvious current challenge to British interests and values. Meanwhile, the UK is executing its Indo-Pacific Tilt to engage in and stabilise a region central to global prosperity and security, a policy reinforced in the Integrated Review Refresh.

The UK’s unique combination of cultural, economic, diplomatic, and military-intelligence tools allow it to play a major regional role absent significant additional financial cost, while also undergirding the other elements of its foreign policy. Executing the Tilt entails an emphasis on the Middle East. The region is the vital commercial hub connecting Europe and Asia, an energy powerhouse, and home to hundreds of thousands of British citizens. The Middle East is therefore central to Eurasian competition. This is in-line with the government’s overall vision, as articulated in the Integrated Review Refresh: Middle Eastern security and prosperity is a vital British interest, to be achieved through the careful application of British diplomatic, strategic, and economic capabilities. Sustaining the Tilt, and shepherding into existence the Atlantic-Pacific partnerships the UK seeks to spearhead, requires a coherent Middle East policy.

Iran is the Middle East’s largest, most aggressive power, with an obvious commitment to revising the global order, and with a growing alliance with Russia. Indeed, the paper’s foremost contribution is to widen British Iran policy: focus on the nuclear issue is correct, but it must be contextualised alongside Iran’s proxy network and support for Russia. Consequently, an effective Iran policy must address the threat’s totality, including the nuclear issue as one among many problems.

As Iran accelerates its nuclear enrichment, the risk increases that Russia assists Iran in nuclear breakout, facilitate advanced military technological transfers, and support Iranian intelligence activities in the UK and the EU. An Iran-Russia axis is as much a European problem, therefore, as a Middle Eastern one.

Now more than ever, as we witness the growing alignment between Iran and Russia, it is imperative for the Government to seriously consider the insights and recommendations put forth in this paper. It is our sincere hope that the insights and proposals put forth in this paper will inform and guide the United Kingdom’s policy decisions toward Iran, enabling us to confront the complex challenges ahead and secure a safer and more prosperous future for our nation and the Middle East as a whole.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

The Middle East matters to British interests. In addition to being the commercial nexus point between Europe and Asia, and the world’s preeminent energy hub, the Middle East is important in terms of European geopolitics, the British economy, national security and migration flows. The region is also home to hundreds of thousands of British citizens.

The UK must see the Middle East in context. The military threat of Russia and the long-term systemic challenge of China require Britain, if it is serious about being a global actor, shaping rather than accepting its strategic environment, to take a Eurasian approach to the Middle East, situating it within a broader context of systemic competition for influence and resources. The Middle East is the backstop of the Indo-Pacific region, giving it long-term importance during any great power rivalry.

The UK’s diplomatic and military toolkit allow it to make a difference in the Middle East. For historic and strategic regions, the UK has deep and longstanding relationships with almost every country in the Middle East. This fact, alongside its UN Security Council membership and military capacity, give it the ability to have an outsized influence on the course of Middle East affairs.

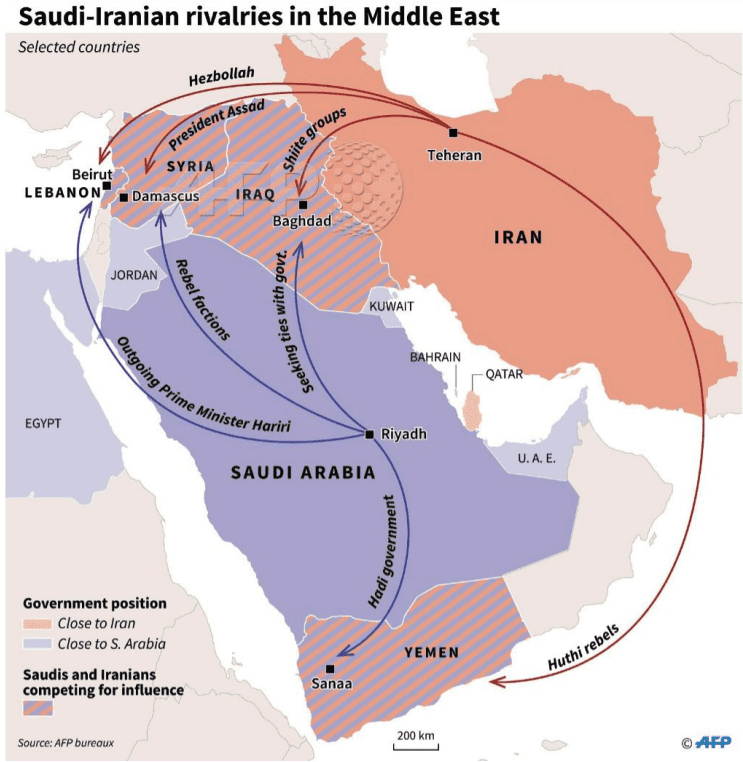

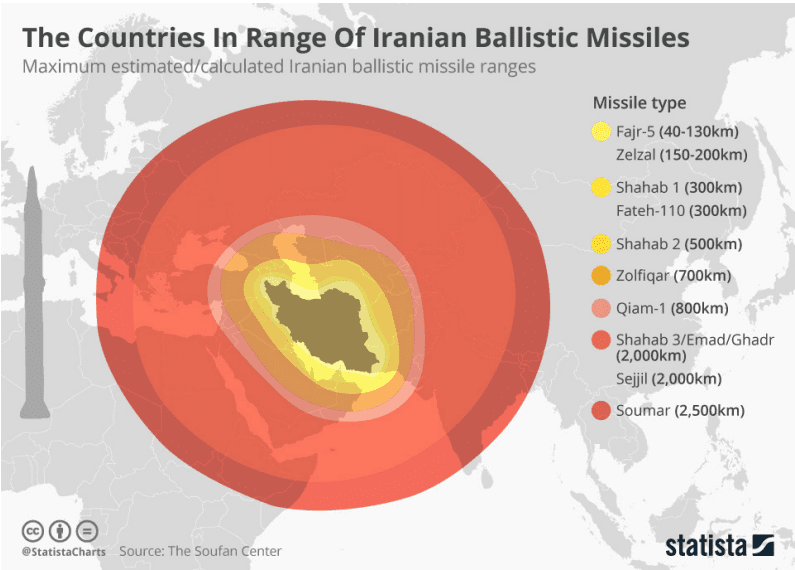

Any Middle East policy requires an Iran policy. Iran is the region’s largest and most geographically secure power, with a revanchist commitment to reshaping the regional and ultimately global order in its own interests. It is a geopolitical hinge between the Middle East, the Trans-Caucasus, and Central and South Asia. It exerts significant influence over Muslim and specifically Shia communities globally. Supported by a wide range of militarised proxies and sympathetic regimes from the Levant through West Africa to South and Central America, its reach is unparalleled by that of any country in the region. It is constructing a land bridge connecting Iran to the Mediterranean (for the first time since late antiquity), and has footholds in Yemen and the Palestinian Territories, giving it leverage over the Middle East’s main naval chokepoints and Britain’s key partners and friends. Every regional actor views the western response to Iran as the defining feature of each country’s Middle East policy.

Iran’s ultimate ambitions extend beyond the Middle East, and beyond the immediate future. Iran is fundamentally committed to creating a new Middle Eastern status quo where it is the region’s dominant power. From this position, it can defend and export the Islamic Revolution, expand effective control of territory, maximise revenues through legitimate and illegitimate channels and deal – regionally at least – with Turkey, Russia and China as equals in a long-term contest for Eurasian mastery.

In the 2010s, Iran shifted from a defensive strategic posture to an expansionist one. Its ambitions grew from solidifying its position in neighbouring states to building a corridor through the Levant to the Eastern Mediterranean, along with a flanking manoeuvre around the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen into the Red Sea. This expansion gave Iran access to, and the potential to control, the Suez-Indian Ocean maritime chokepoint (in addition to the Straits of Hormuz), generating a long-term threat to regional stability, global energy markets and trade between Europe and Asia.

The Iran threat is not simply the nuclear issue, but a combination of Iranian military capabilities, proxy groups, intelligence and influence tools in the UK and elsewhere, and the nuclear programme. The most obvious failure of Western policy, and particularly British and European policy, has been to compartmentalise the nuclear issue diplomatically and then treat this as the central policy issue in relations with Iran. Nuclear developments, while an important part of the package, must be situated within a more comprehensive understanding of the wider threat posed by Iran. Iran policy, meanwhile, must begin with the strategic threat that Iran poses, not the single, symptomatic element that is its nuclear programme.

Iranian expansion across the Middle East will continue unless there is a Western – and indeed a regional Arab – policy change. Iran has links with proxies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen, as well as enduring if sometime oscillating relationships with Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) and Hamas. The longer Iranian regional expansion is left unchecked, the more Iran will cement its hegemony over significant parts of the Levant, Iraq and the southern Arabian Peninsula, intensify its efforts to undermine and eventually destroy Israel and expand its presence beyond the Middle East.

Iran will soon expand its support to Russia’s war in Ukraine. Having already transferred drones to Russia, Iran is likely soon to begin transfers of advanced ballistic missiles to the Kremlin. In October, under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), sanctions on Iran’s ballistic missile exports will lapse, making such transfers legal under international law. Iran has also accelerated its programme of nuclear enrichment, reaching the cusp of weapons-grade uranium and developing centrifuge and other related technologies at existing and new sites. Iranian nuclear advancement and military assistance to Russia – like Iran an increasingly hostile revanchist power with shared interests in Syria – increase the odds that President Putin, with the right incentives, will see advantage in assisting Iran with nuclear breakout, transferring advanced military technology, and supporting Iranian intelligence activity in Europe and the UK.

The Iran-China Relationship, demonstrated by the recent Chinese-brokered normalisation deal with Saudi Arabia, is also set to transform the Middle East and undermine British and wider western interests. The normalisation agreement is only the most recent step in a broader Chinese Middle East policy to which Iran is central, and through which China hopes to secure long-term access to regional energy resources, captive markets for its products and significant control over both land-based and maritime trade routes, naval bases. In doing so, Beijing doubtless hopes to reduce the dependence of the UK’s traditional regional partners on western security and other guarantees. Iranian-Chinese trade has skyrocketed since the Ukraine War began, as China takes advantage of illicit Iranian and transshipped Russian oil. China has also expanded its economic footprint in Iran and its strategic footprint in East Africa. The UK’s Indo-Pacific Tilt, as described in the Integrated Review, was a sound strategic framework: an Iran policy is a necessary complement to this.

Iran has thorough sub-threshold capabilities, including operatives within the UK and links to transnational organised crime. Iran simultaneously claims the legal rights of a traditional polity and contravenes international law, allowing it to act in concert with organised criminal entities, conduct assassinations and kidnappings abroad, and participate in the international drug trade. In the last 15 months, MI5 Director Ken McCallum and Counterterrorism Policing lead Matt Jukes have identified 12 to 15 cases of Iranian plots within the UK against British citizens or Iranian dissidents. These statements are in line with those of the Director of the FBI, Christopher Wray, pointing to more intense Iranian intelligence activity in the past two years.

Iran is a theocracy ruled by a clerical elite that lays claim to the leadership of the Islamic world, and is theologically opposed to the West. Iran’s 1979 constitution claims a mandate over the entire Islamic world and demands an interventionist foreign policy on behalf of the “world’s oppressed”. Its founding was premised on a narrative of British and American duplicitousness. A systematically anti-British, anti-American and anti-western foreign policy is the logical corollary.

The short-term chances for political reform inside of Iran are minimal. Iran’s “deep state,” comprising the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps and hardline clerics, is now in complete control of Iran’s domestic and foreign policy. Since 2019, Iran’s ‘reform movement’ has been neutered.

Iranian domestic instability increases the likelihood of conflict. The looming death of Iran’s 83-year-old Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei will likely lead to a succession directed by the most aggressive elements of the Iranian state. This incentivises both Iranian nuclear breakout and makes an Israeli strike on Iran more likely.

Now is the time for a new Iran policy. In addition to Iran’s highly-publicized human rights violations, Iran’s alignment with Russia and deepening economic alignment with China are part of a larger project to reshape the present regional and international orders. Iran’s nuclear program is more advanced than ever, raising the likelihood of an escalation that threatens British interests—and citizens— in coming years. Iran’s domestic politics incentivise a more aggressive foreign policy. Moreover, whatever the outcome of the Ukraine War, the Russian military will require at least two to three years, and perhaps as long as a decade, to reconstitute itself. Combined with Eastern European NATO’s major defence expansion, this decreases the immediate threat that the UK will face from Russia in Europe, freeing up resources for a more concerted strategic focus on the Middle East.

Absent decisive action, the UK risks accepting both a nuclearised Middle East and persistent Iranian strategic expansion. An Iranian nuclear arsenal will trigger regional proliferation and increase sub-threshold rivalry in the Middle East that raises the likelihood of direct confrontation. Iran thrives off ungoverned spaces generated by major military conflicts. As we have repeatedly seen, its Arab neighbours do not have the military capacity to resist or roll back Iranian gains. This means Iranian expansion is likely to continue unabated unless there is a collective and systematic western response to it. Moreover, without an Iran policy, the UK risks facing a major regional conflict, that will put at risk the British economy and hundreds of thousands of British citizens, without the capacity for a serious and effective response.

British strategy must go beyond preserving the status quo. Indeed this no longer exists. Two decades of Iranian expansion and regional turmoil (including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) have produced a new and evolving balance of power that currently favours Iran. British policy objectives should include maintaining freedom of access to and movement through the Middle East’s maritime chokepoints, in coordination with allies the defence of British partners and friends including Israel and the Gulf States, and the limitation of Iranian strategic disruption beyond the Middle East. Establishing a favourable balance of forces requires diplomatic, economic, intelligence, ideological, and military steps to undermine Iranian expansion, pressure the Iranian regime, and credibly threaten an overwhelming response to Iranian escalation and reprisals against Iranian attacks in the UK.

Listed Recommendations

Diplomatic steps to isolate Iran and support a stable Middle Eastern coalition:

- In consultation with the US, the EU, France, and Germany, trigger the JCPOA’s Snap-Back Process to isolate Iran, ensure international support for an anti-Iranian coalition, and force the issue over Iran amongst the JCPOA’s signatories;

- Pursue security and intelligence partnerships with the key powers surrounding Iran. This should include Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, and Israel.

- Work with Turkey and Azerbaijan in the Caucasus alongside the UK’s European partners to undermine the developing Russia-Iran Caspian Sea trade corridor – absent a greatly expanded regional footprint, the corridor will develop unimpeded;

- Conclude a GCC-wide FTA and expedite arms sales to push back against Iranian pressure against the Arabian Peninsula;

- Expand the 2021 UK-Israel Strategic Partnership through an innovation-focused Free-Trade Agreement to solidify the UK-Israel relationship for a period of long-term competition with Iran and ensure participation in major regional military exercises alongside the U.S. and Israel.

Soft Power, Social Cohesion, Intelligence, and Human Rights: to disrupt Iranian networks in the UK, leverage British cultural assets, and expose Iranian criminal acts and domestic brutality;

- Stand up a hybrid public diplomacy and intelligence capacity, either as an interagency group or a small separate team, to integrate intelligence analysis and an understanding of Iranian messaging with British public diplomacy strategies to identify and counter Iranian subversive messaging in a more timely and effective way;

- Revive soft power tools, particularly BBC Persian’s Radio Service, through proper financing and staffing to connect directly with the Iranian people; reorient other relevant regional services like BBC Azeri, Arabic, Pashto; and stand up a BBC Balochi Radio Service;

- Create language scholarship programmes through FCDO that prioritise critical Middle Eastern languages, including Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Azeri, Balochi, Pashto, and Dari to revive British linguistic talent so critical for the security services, intelligence, and public diplomacy;

- Use intelligence assets within Iran to identify human rights violations and amplify those violations globally to win the narrative battle against Iran by reporting Iranian human rights violations to major news outlets and opposition media.

- Expel Iranian diplomats in the UK suspect of having intelligence links, and greatly increase the stringency of diplomatic visas issued to Iranian consular personnel to undermine Iranian intelligence in the UK by depriving Iran of official cover agents.

Financial Intelligence to enhance sanctions prosecution and ensure better UK enforcement:

- Stand up an executive sanctions enforcement capacity to ensure the UK actually regulates potentially illicit cash within its financial system, patterned off the United States Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

- Break down bureaucratic barriers for Financial Intelligence by empowering the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI), expanding its staff to around 200 from 70 employees, and reorganising the NCA’s Financial Intelligence (FININT) capabilities to provide this newly-empowered OFSI with an actually responsible analytical capability.

Counterterrorism steps to integrate intelligence, law enforcement, and military capabilities:

- Revive the whole-of-government counterterrorism approach developed originally to counter AQ and IS to ensure proper bureaucratic coordination between different parts of the British government to limit Iranian actions, potentially even empowering and modifying the office of the Head of the Joint Intelligence Organisation (JIO) to make it more adaptable, efficient, and responsive during a period of strategic competition with Iran.

- Increase police and Security Service focus on both open and covert Iranian regime activities to prevent assassinations and kidnappings in the UK, including by tasking the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre and National Crime Agency’s intelligence capabilities, along with MI5 and MI6 to hire more Persian analysts and better fuse MI5, MI6, and NCA capabilities.

Legal and Regulatory Modifications to make the British state more capable of acting in the grey zone:

- Use the National Security Bill as a vehicle to replicate proscription to empower British law enforcement and break the war-peace binary without triggering the potentially adverse effects on British terrorism law that might arise from the designation of Iran as a state terrorist organisation;

- Employ Regulation to limit IRI illicit finance by tasking the FCA and other regulatory bodies with more aggressive enforcement and auditing, particularly against companies and charities with potential ties to Iran.

- Disrupt Iran’s dark tanker fleet by enforcing and if necessary strengthening the requirements for British companies and British-flagged ships to verify oil and gas transactions.

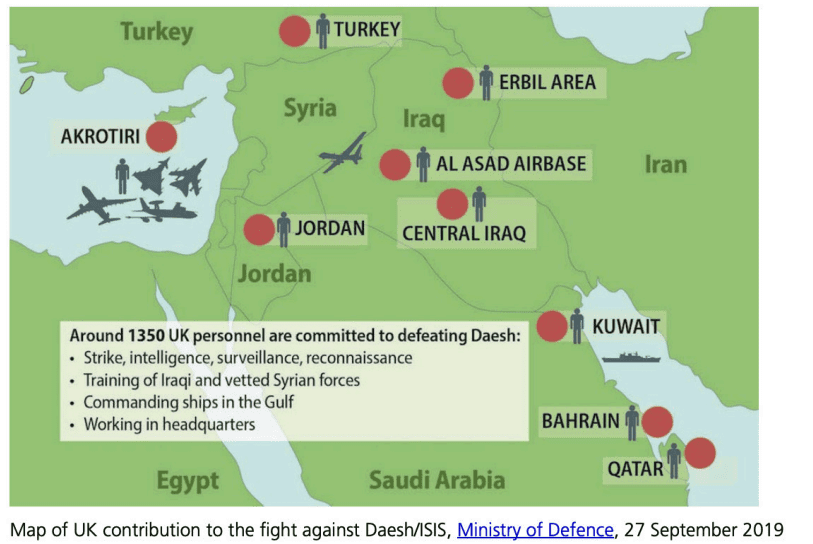

Military and Intelligence activity in the Middle East that appreciably – through strategically sound deployments – influences the regional balance of forces and bolsters deterrence:

- Bolster strategic communications efforts to link the Middle East to other regions, using the Indo-Pacific Tilt as a heuristic, and highlighting the Middle East’s strategic relevance to European and Indo-Pacific security;

- Improve the UK’s ability to attack the Iranian international network by reinforcing the mechanisms the UK created to respond to non-state actors and adapting them to the Iran threat;

- Expand the capabilities necessary for the UK to deploy to the Middle East as a crucial coalition member, including improving British heavy airlift surface combatant units in the long-term, thereby demonstrating British commitment and reinforcing long-term deterrence;

- Conduct limited redeployments towards the Middle East to maximise operational returns and improve short-term deterrence, including by retasking British drones to the region and relying on new autonomous technologies;

- Review evacuation plans for British citizens in light of the Afghanistan and Sudan evacuations, and with the recognition of the sheer scale a Gulf evacuation

Introduction: The Middle East and the UK

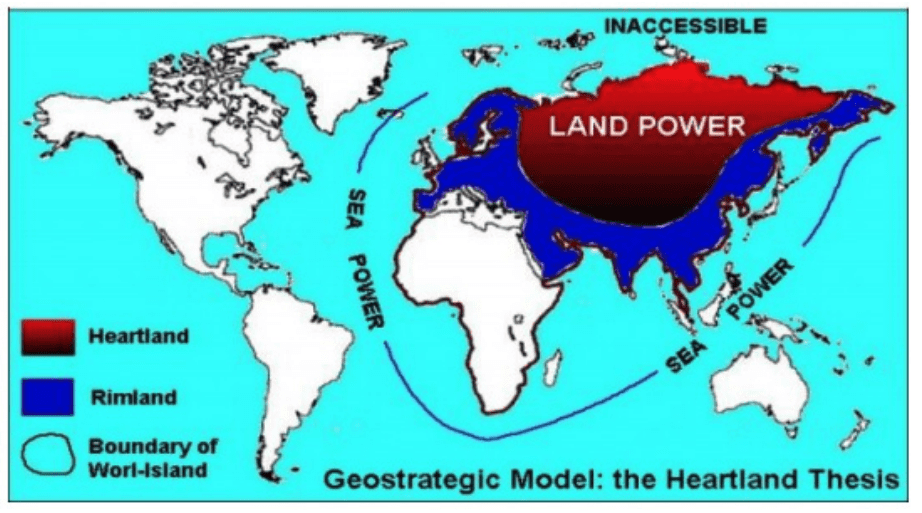

The 2021 Integrated Review recognised the reality of a fragmented international system, “characterised by intensifying competition between states over interests, norms and values”.1Global Britain in a Competitive Age (March 2021), 11. Russia’s 24 February 2022 escalation of its war against Ukraine has demonstrated this trend in real time, as the UK and its allies confront the largest European ground war since 1945.2Edward Stringer, “Ukraine Reinforces the Case for the Integrated Review”, Policy Exchange, 21 March 2022, accessed via: https://policyexchange.org.uk/blogs/ukraine-reinforces-the-case-for-the-integrated-review/. In this context, British strategic debate increasingly points to a binary choice between the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic.3See David Lammy’s Chatham House Speech, 24 January 2023, accessed via: https://labour.org.uk/press/david-lammy-speech-to-chatham-house/. In reality, however, the present competitive age is another contest for Eurasia, the world’s largest geographical region that includes the majority of the world’s population, resources, and GDP.4Eurasia runs from the French Atlantic coastline to the South and East China Seas, from the most remote reaches of Siberia to southern India.

FIGURE 1: MAP OF EURASIA

Figure 1: A Map of the World Under the Strategic Heartland-Rimland thesis, accessed via: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/279/27964799050/html/

Maritime trade facilitates 95% of all British trade.5State of the Maritime Nation 2019 (Maritime UK), 5. It is therefore of crucial importance to ensure that major Eurasian chokepoints remain open, connection regions between these chokepoints unimpeded, and the links from chokepoints to resources farther within Eurasia are uninterrupted. British policy cannot therefore focus on one region. The UK must have a policy for every Eurasian region, or risk being at the mercy of strategic trends over which it has no control.

The Integrated Review articulated an Indo-Pacific approach which balanced the acute military threat of Russia, and a long-term focus on Asia. Its result was the Indo-Pacific Tilt.6Global Britain in a Competitive Age, 66. However, the Integrated Review paid insufficient attention to the crucial link between Europe and Asia, the Middle East. Nine-tenths of global trade are still carried by ship, making the Middle East, with its expansive Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean littorals a far more viable trade route than Central Asia. The Middle East contains three globally significant maritime chokepoints – the Suez Canal, Bab-el-Mandeb, and Strait of Hormuz – which generate the region’s massive commercial hubs like Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah, Oman’s Port Salah, Qatar’s Port Hamad, the UAE’s Port Khalifa, and Israel’s Haifa Port.7“Middle East Container Ports Are the Most Efficient in the World”, World Bank, 25 May 2022, accessed via: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/05/25/middle-east-container-ports-are-the-most-efficient-in-the-world. Threats to Middle Eastern trade drove British Middle East policy until the 1970s.8Magnus PS Persson, “Recent Literature on British Policy in the Middle East, 1945-67”, Contemporary European History, 14:2 (May 2005), 271-276.

FIGURE 2: MAP OF THE MIDDLE EAST

Figure 2: A strategic map of the Middle East, accessed via: https://twitter.com/afp/status/943496223968907267?lang=en-GB

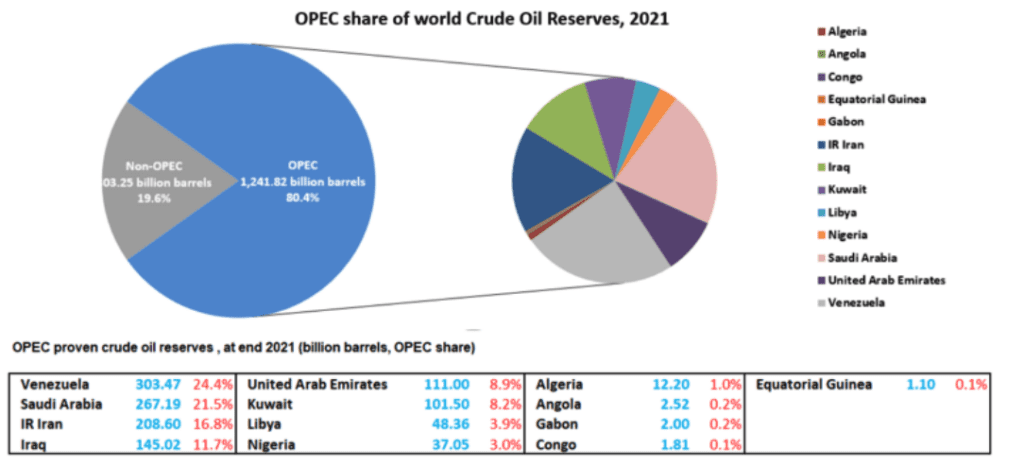

Energy security intensifies the region’s importance. OPEC’s Middle Eastern members control nearly 60% of the world’s proven crude oil reserves.9Data from OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2022, accessed via: https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm. Europe, the UK, and the UK’s Asian allies still rely overwhelmingly on these energy reserves, as do British adversaries.

FIGURE 3: OPEC SHARE OF WORLD CRUDE

Figure 3: OPEC Share of world crude oil reserves, accessed via: https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm

Iranian Ideology-Mythology and the UK

As the diplomatic joke goes, Iran is the last country to still consider the UK a great power.

The UK reduced its Middle Eastern presence in 1971. But ideologically, Iran places the UK, along with the U.S. and Israel, at the heart of its historical mythology. In this scheme, the United States is the ‘Great Satan’ and Israel the ‘Little Satan’ that must be defeated to consummate Iranian power. The UK, in turn, is the ‘Middle Satan’, Iran’s alleged great humiliator. British de facto partitions of Iran in 1907 and 1941 played a significant role in Iranian revolutionary thought. When nationalist Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh nationalised the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) in 1953, the UK played a leading role in deposing him. This historical mythology makes Iranian antagonism towards the UK part of the Islamic Republic’s political DNA.

| 1953 IRAN |

| The Iranian regime’s grievance narrative places the UK at its centre. Under this telling, the UK and U.S. deposed the democratically-elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, to ensure British access to Iranian oil in an act of singular perfidy. The truth is rather different

In 1951, the Persian majlis nationalised the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), legally a British possession, prompting Mohammed Reza Shah to appoint Mossadegh, an aristocratic elder statesman, arch-nationalist, and thorough Anglophobe, as prime minister.10Gregory Brew, “The Collapse Narrative: The United States, Mohammed Mossadegh, and the Coup Decision of 1953”, Texas National Security Review, 2:4 (August 2019), 39-44. See also Ray Takeyh, “The Coup Against Democracy That Wasn’t”, Commentary (December 2021), accessed via: https://www.commentary.org/articles/ray-takeyh/iran-1953-coup-america/. Mossadegh, appointed as prime minister in Iran’s factional, elitist political system, was a long-term fixture of Iranian politics, who had previously retired in 1947. Mossadegh was intransigent throughout US-brokered negotiations, seeking a maximalist arrangement that would provide Iran with all oil revenues from the seized AIOC fields while ensuring Western technical assistance for their operation, and rejecting multiple U.S.-offered compromises. Meanwhile, by 1953, the Iranian economy had collapsed due to an oil embargo and a lack of Western technical assistance. Iranian domestic politics became increasingly unstable, and the country vulnerable to Soviet influence. The Korean War still raged at the time and, just seven years earlier, the Soviets sought to bite off northwestern Iran through two puppet states, indicating the Kremlin’s designs on the region.11. Louise Fawcett, “Revisiting the Iranian Crisis of 1946: How Much More Do We Know?” Iranian Studies, 47:3 (May 2014), 379-399. Mossadegh’s actions throughout 1952-1953 convinced every centre of Iranian power – the bazari merchants, the aristocratic old politicians, the military, and the clergy with their connections to the countryside – that Mossadegh was a long-term threat to Iran’s prosperity. The military and political figures put out feelers to the U.S. and UK embassies throughout Mossadegh’s premiership, but only in March-June 1953 did the U.S. and UK acquiesce to Iranian-led resistance. As economic difficulties intensified and Mossadegh’s popularity amongst the Iranian elite and people decreased, he sought to consolidate power. On 3-10 August, Mossadegh held a referendum on the dissolution of parliament, conducted without secret ballots, and on 16 August dissolved parliament. During a confused four-day period, the Iranian military executed a coup with the UK and US’ backing, but nevertheless as the primary actors in the drama. The simplistic narrative, that American fear of communism and British perfidy drove a democrat from power in 1953, is simply untrue. Cold War geopolitics and energy questions did intersect with Iranian domestic issues to generate the 1953 coup, but it was those domestic factors – and Mossadegh’s fundamental unpopularity – that led to his removal. |

The Physical Threat

Hundreds of thousands of British citizens live in the Middle East. In the UAE alone reside over 120,000 British expatriates.12Alice Haine, “British expatriates move to UAE in search of new lifestyle after Covid-19 and Brexit”, The National News, 18 September 2021, accessed via: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/money/2021/09/18/british-expatriates-flock-to-the-uae-for-new-life-away-from-covid-and-brexit/. British business connections in the UAE are robust, with 6,000 British-registered companies located in the UAE. 20,000-plus Brits live in Saudi Arabia, while around 5,000 live in Kuwait.13See “Brits Abroad”, BBC, accessed via: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/in_depth/brits_abroad/html/mid_east.stm; “See also Kubi Kalloo, Understanding and engaging with UK expats in the UAE”, Visit Britain, research conducted March-April 2021, accessed via: https://www.visitbritain.org/sites/default/files/vb-corporate/uk_expats_in_the_uae_research.pdf. Around 500-600 Brits move to Israel each year, while 150,000-plus Brits travel to Israel for various reasons annually.14Jenni Frazer, “See-saw demography: Israelis in the UK vs. British aliyah”, Times of Israel, 24 November 2015, accessed via: https://www.timesofisrael.com/see-saw-demography-israelis-in-the-uk-vs-british-aliyah/. In the event of a serious security contingency in the Middle East, a considerable number of British citizens would be on the front line. Iran frequently employs kidnapping to extract leverage from international targets. In recent years, Iran has arbitrarily detained dozens of British nationals, including the high-profile case of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and more recently, executed British-Iranian dual national Alireza Akbari.15Philip Loft, “Dual nationals imprisoned in Iran”, House of Commons Library (Research Briefing 8147, 17 January 2023), 4. Iran has also kidnapped British nationals in the UAE16“UAE arrests Iranians suspected of kidnapping Briton in Dubai”, Reuters, 9 January 2014, accessed via: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-iran-emirates-idUKBREA080RQ20140109. and has used kidnappings against its geopolitical rivals, attempting to abduct and murder Israeli tourists in Turkey.17“Iranian kidnapping of Israeli tourists said thwarted in Turkey last month”, Times of Israel, 12 June 2022, accessed via: https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-said-to-have-helped-foil-planned-iranian-attack-on-israeli-targets-in-turkey/.

More broadly, a regional conflict would be severely disruptive to the British economy. The Middle East accounts for 5% of British exports and 2% of its imports.18See ONS Data as of 16 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade. Since February 2022, the UK imported more oil individually from Saudi Arabia and the UAE than from Russia, and imported well over double the oil volume from the Middle East than from Russia.19Hannah Donnarumma, “Trends in UK imports and exports of fuels”, ONS, 29 June 2022, accessed via: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/articles/trendsinukimportsandexportsoffuels/2022-06-29. A regional contingency would thus amount to a substantial supply contraction and would cause oil prices to skyrocket. Moreover, 12% of global trade transits the Suez Canal. The UK imports the majority of spices, various oils, meats, and wine from Asia, all of which must transit the Suez Canal. Moreover, the EU, the UK’s largest trading partner, imports around a quarter to a third of its goods from Asia, the majority of which must also transit the Suez Canal.20Jeremy Domballe, “Maritime trade and its risks: EU’s imports from Asia and the Middle East”, S&P Global, 2 July 2020, accessed via: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/maritime-trade-and-risks-eu-imports-from-asia-and-middle-east.html. Any disruption to the Suez-Indian Ocean maritime route, therefore, would cause broader dislocation to Europe, with knock-on effects in the UK.

Given the destabilising potential of a Middle Eastern conflict and the direct threat that conflict poses to British interest, it is incumbent upon British policymakers to articulate a Middle East strategy that deters and manages regional escalation. Iran is the primary, and fundamentally only, instigator of a major potential conflict, meaning that any Middle East policy must begin with Iran.

Iranian Objectives

Iran’s long-term goal is to become the Middle East’s dominant power, thereby preserving the Islamic Revolution indefinitely, exporting it to the rest of the Muslim world, and gaining the leverage to deal directly with other great powers, particularly Russia and China.

Iran’s theocratic political model of Islamic Republicanism is not limited to Iran. Rather, the Islamic Revolution, the Iranian regime’s term for the 1979 overthrow of the Shah, was meant to begin a broader revolution in the Islamic world. Nor is Iranian ambition limited to Shia-majority areas. Iran considers itself the Islamic world’s natural leader, and seeks to export the Islamic Revolution first to areas with major Shia populations like Iraq, Lebanon, and parts of Syria, and then to the Islamic world more broadly.

By uniting the Islamic world under the Iranian banner, Tehran hopes to preserve the Islamic revolutionary regime indefinitely. Insulated by a buffer of friendly Islamic states, and directly or indirectly controlling the majority of the world’s oil reserves, Iran would be immune to long-term economic pressure. This Iran, likely armed with nuclear weapons, could expand conventional and advanced military capabilities to expand its influence in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean.

A united Islamic world under Iranian leadership, meanwhile, would be a bona fide great power, the first Islamic great power since the Ottoman Empire, and the first Middle Eastern actor capable of projecting power beyond the region since the early 19th century. An emboldened, empowered Iran would be able to negotiate with Russia and China, the other Eurasian authoritarians, on reasonably equal terms. It would also be able to extend its influence throughout Eurasia and even gain allies in the Americas, likely first turning to Venezuela and Cuba, and then to other Latin American states hostile to the Anglo-Euro-American international system.

In short, then, Iran’s long-term strategic objective is great-power status.

The COVID-19 Pandemic, Russian invasion of Ukraine, and growing Chinese threat to Indo-Pacific security and stability all indicate a renewed era of systemic great power competition, which the Integrated Review’s first draft and refresh clearly recognise.21Global Britain in a Competitive Age, 17. The emergence of a third authoritarian great power in Eurasia would acutely undermine British economic and strategic security, threaten British allies, and create a balance of forces hostile to British values and the liberal international system those values support.

Moreover, Iran’s concerted campaign to gain great power status has destroyed the Middle Eastern status quo. The Prime Minister has already signalled a departure from status quo thinking in the Indo-Pacific.22“PM speech to the Lord Mayor’s Banquet: 28 November 2022”, 28 November 2022, accessed via: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-to-the-lord-mayors-banquet-28-november-2022. Absent a Middle East status quo, the UK’s objective should be to cultivate a regional balance of forces that preserves Britain’s interests in regional commerce, the respect for national borders, and the defence of its allies.

Every aspect of the Iran threat – its non-violent subversion within the UK, its intelligence activity and assassinations beyond the Middle East, its kidnappings and pressure on dissidents, its illicit cashflow through its links with organised criminal groups, and its nuclear and conventional military expansion – all stem from Iran’s principal objective of great-power status, and are all meant to establish a new balance of forces.

Next chapterThe Structure of the Iran Threat

The Iran threat has crystallised given Tehran’s active support for Russia in Ukraine and repeated violations of human rights during the 2022-2023 Mahsa Amini protests. The threat from Iran itself is not new – it evolved throughout the 2010s as Iranian power and ambition increased. However, Iran’s increasingly robust relationship with Russia, and now China, have made it a particularly acute threat to Middle Eastern peace and, of equal importance, given Iran a legitimately global reach. Indeed, the recent Chinese-brokered normalisation between Iran and Saudi Arabia demonstrates the degree to which the regional balance of forces has shifted in Iran’s favour.

Human Rights, Terrorism and Organised Crime, and Social Cohesion

Iran’s internal repression dovetails with its support for terrorism, intelligence network in the UK, Europe, and Middle East, and active meddling in British society and politics. British Iran policy must therefore consider Iran’s human rights violations and connect them to its support for terrorism and organised crime, and its intelligence activity. For Iran, there is no distinction between the domestic and the international, meaning Iranian activity abroad is a coherent aspect of Iranian strategy more generally.

The killing of Mahsa Amini has sparked a protest wave in Iran reminiscent of the 2009-2010 Iranian Green Movement.23Nicole Winchester, “Protests in Iran: Death of Mahsa Amini”, House of Lords Library (21 October 2022), accessed via: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/protests-in-iran-death-of-mahsa-amini/. The regime turned to its security services to crack down upon the protestors. Since the protests began on 16 September 2022, several hundred Iranians, including British-Iranian dual nationals, have been executed, and an estimated 20,000 Iranians have been imprisoned.24Iran Protests 2022 -Detailed Report of 82 Days of Nationwide Protests in Iran (Human Rights Activists News Agency, December 2022), 57ff. The U.S. Department of State’s 2022 Iran Human Rights Report identified 500 Iranians killed by the regime’s security services, including 69 children.25Iran 2022 Human Rights Report (U.S. Department of State, 20 March 2023), 40. The Iranian security services actively target suspected resistance organisations including teachers’ associations and other groups, impinging upon freedom of association and disrupting civil society.26Ibid., 40-43. Iran frequently employed torture, deprivation, and sexual violence to force confessions from jailed dissidents.27Ibid., 9. Moreover, the Iranian state is noticeably more violent against ethnic minority dissidents than others.28Ibid., 59.

Below is an excerpt from the 2021 report describing the torture of two Balochi-Iranians, Hassan Dehvari and Elias Qalandarzehi, arrested on spurious political charges:

In the (Ministry of) Intelligence (detention center), we were subjected to physical and psychological torture including being threatened with rape, tying us to the “miracle bed” (a bed used for flogging prisoners), all types of instruments, like whips, cable wires, a metal helmet that would be wired with electric shocks to our heads, attempting to pull out hand and toe nails, turning on an electric drill and threatening to drill our arms and legs, bringing my wife and a video camera and [telling] me that either I accept the charge or they would rape her and film it in front of me.29Ibid.

Both Dehvari and Qalandarzehi were tortured for months before their executions in early 2021.

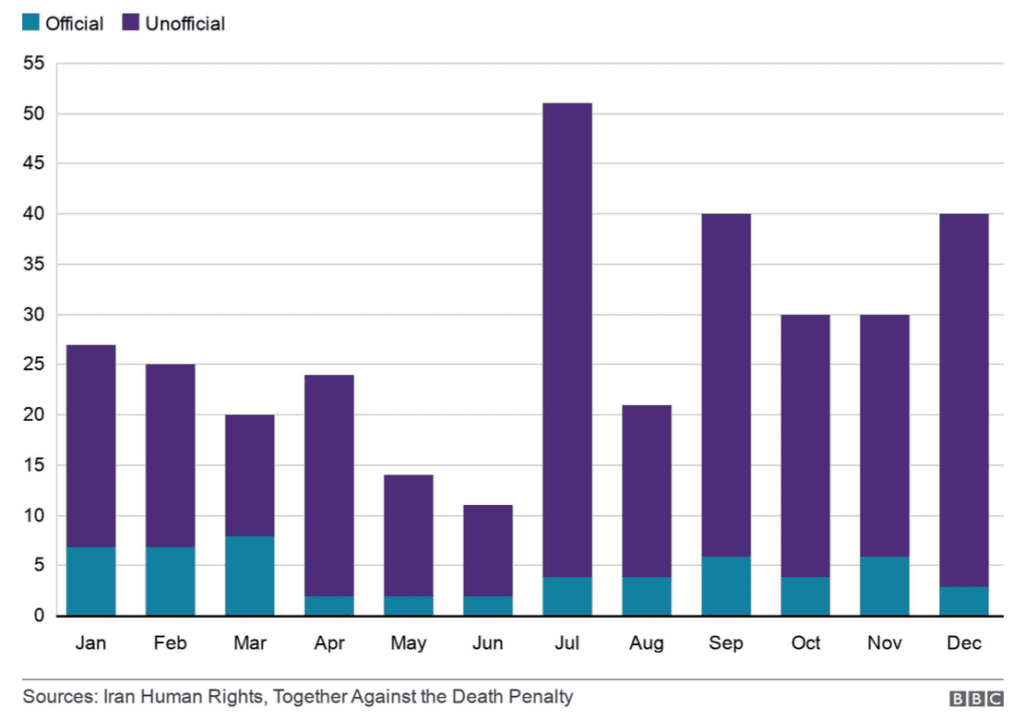

FIGURE 6: EXECUTIONS IN IRAN

Figure 6: Iranian execution data in 2021, accessed via: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-61256213

Iran’s 1979 Constitution and legal code permit punishments including stoning, executions, and amputations, limits free expression and political participation, and explicitly enshrines a second-class role for women.30See the Preamble to Iran’s 1979 Constitution, accessed via: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iran_1989.pdf; See also the translations of Books 1 and 2 of the Iranian Penal Code, accessed via: https://iranhrdc.org/english-translation-of-books-i-ii-of-the-new-islamic-penal-code/. Iran further has one of the highest execution rates in the world – since 2010, it has been second only to China in its application of the death penalty.31Amnesty International Global Report: Death Sentences and Executions 2021 (Amnesty International, 2022), 10. These violations are possible only because of its robust security apparatus. At its heart is the IRGC, a hybrid internal security, external action, and warfighting service that prosecutes Iran’s foreign interventions. IRGC officers receives the bulk of preferential state positions, while the organisation receives priority for funding and general influence over the Iranian state.32Saeid Golkar, “Iran’s Coercive Apparatus: Capacity and Desire”, Washington Institute, 5 January 2018, accessed via: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/irans-coercive-apparatus-capacity-and-desire.

The IRGC includes several regional commands, each of which trains and equips IRGC divisions and brigades.33Marie Donovan, Nicholas Carl, and Frederick W. Kagan, Iran’s Reserve of Last Resort: Uncovering the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Ground Forces Order Of Battle (AEI Critical Threats Project, January 2020), 5-7. Below this is the Provincial Guard, a province-level devolvement of the IRGC that operates in 32 independent cells, corresponding to Iran’s first-order organisational system.34Saeid Golkar, “Taking Back the Neighborhood: The IRGC Provincial Guard’s Mission to Re-Islamize Iran”, Washington Institute (June 2020), 6. The Provincial Guard is responsible for the Basij paramilitaries, a five million strong force of reservists that provide invaluable additional public security manpower. The Basij system also cross-pollenates with the police – since 2007, the majority of new Iranian police recruits are also Basij members, increasing the IRGC’s control of the security system.35Golkar, “Iran’s Coercive Apparatus”.

Table 1: Iranian Assassination Attempts

| Year | Location | Target | Reason |

| 197936“Shahriar Shafiq”, Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, accessed via: https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/-7088/shahriar-shafiq. | Paris, France | Shahriar Shafiq | Shah’s Nephew |

| 198037Felicity Barringer and Donald P. Baker, “Anti-Khomenini Iranian Slain at Bethesda Home”, Washington Post, 23 July 1980, accessed via: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/07/23/anti-khomenini-iranian-slain-at-bethesda-home/980dc4ea-9af1-4b54-9594-099059657748/. | Bethesda, Maryland | Ali Akbar Tabatabaei | Iranian dissident |

| 198438John Vinocur, “Exiled Iranian General Is Killed With Brother By Gunmen In Paris”, The New York Times, 8 February 1984, accessed via: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/02/08/world/exiled-iranian-general-is-killed-with-brother-by-gunmen-in-paris.html. | Paris, France | Gholam Ali Oveisi | High-ranking Imperial military officer |

| 198739“Hamid Reza Chitgar”, Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, accessed via: https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/-4371/hamid-reza-chitgar. | Vienna, Austria | Hamid Reza Chitgar | Iranian Communist |

| 198940“Abdol Rahman Qasemlu Ghassemlou”, Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, accessed via: https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/30421/abdol-rahman-qasemlu-ghassemlou. | Vienna, Austria | Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou | Iranian Kurdish Political Figure |

| 198941“3 Iranian Kurdish Nationalists Killed”, Deseret News, 15 July 1989, accessed via: https://www.deseret.com/1989/7/15/18815470/3-iranian-kurdish-nationalists-killed. | Vienna, Austria | Abdullah Ghaderi Azar | Iranian Kurdish Political Figure |

| 199042“No Safe Haven: Iran’s Global Assassination Campaign”, Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, 3 February 2011, accessed via: https://iranhrdc.org/no-safe-haven-irans-global-assassination-campaign/. | Nynäshamn, Sweden | Karim Mohammedzadeh | Kurdish Dissident |

| 199043“Assassination of Professor Kazem Rajavi on political grounds”, UN. Subcommission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities (42nd sess. : 1990 : Geneva), accessed via: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/102253?ln=en. | Coppet, Switzerland | Kazem Rajavi | NCRI Representative, former Iranian UN Ambassador |

| 199044Muhammad Sahimi, “The Chain Murders: Killing Dissidents and Intellectuals, 1988-1998”, PBS Frontline, 5 January 2011, accessed via: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2011/01/the-chain-murders-killing-dissidents-and-intellectuals-1988-1998.html. | Konya, Turkey | Elî Kaşifpûr | KDPI Figure |

| 199045Faramarz Davar, “Diplomat Assassins: Who Does Iran Kill Abroad and Why?” Iran Wire, 18 November 2021, accessed via: https://iranwire.com/en/features/67508/. | Västerås, Sweden | Efat Ghazi | KDPI Figure |

| 199146https://www.independent.co.uk/news/lifeinfocus/shapour-bakhtiar-exiled-assassinated-prime-minister-iran-pahlavi-era-a8474656.html | Suresnes, France | Shapour Bakhtiar | Former Iranian Prime Minister |

| 199247Homa Katouzian, “A Life in Focus: Shapour Bakhtiar, the last prime minister of Iran’s Pahlavi era”, The Independent, 11 August 2018, accessed via: https://www.rferl.org/a/farrokhzad-murder-persons-of-interest/31566368.html. | Bonn, Germany | Fereydoun Farrokhzad | Iranian Dissident |

| 199248“Dr Sharafkandi”, PDKI, accessed via: https://pdki.org/english/dr-sharafkandi/. | Berlin, Germany | Sadegh Sharafkandi | KDPI Leader |

| 199249“Fattah Abdoli”, Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, accessed via: https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/33127/fattah-abdoli. | Berlin, Germany | Fattah Abdoli | KDPI Figure |

| 199250“Homayun Ardalan”, Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, accessed via: https://www.iranrights.org/memorial/story/33126/homayun-ardalan. | Berlin, Germany | Homayoun Ardalan | KDPI Figure |

| 199251Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Germany/Iran: Details of the assassination of four Kurdish politicians in 1992 at the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin, 16 November 1999, ZZZ33188.E, accessed via: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6ad824c.html. | Berlin, Germany | Nouri Dehkordi | KDPI Figure |

| 199652“Report on the Islamic Republic’s Terrorism abroad”, accessed via: https://princessashrafpahlavi.org/en/8-artciles/27-report-on-the-islamic-republic-s-terrorism-abroad. | Stockholm, Sweden | Kamran Hedayati | Kurdish Dissident |

| 201553Daniel Boffey and Martin Chulov, “Death of an electrician: how luck run out for dissident who fled Iran in 1981”, The Guardian, 14 January 2019, accessed via: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/14/a-dutch-electricians-raises-issues-of-trust-in-iran. | Almere, Netherlands | Mohammad-Reza Kolahi Samadi | MEK Member |

| 201754“Gem TV: Iranian CEO Saeed Karimian shot dead in Istanbul”, BBC, 30 April 2017, accessed via: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-39761451. | Istanbul, Turkey | Saeed Karimian | Television Executive |

| 201755Anthony Deutsch and Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “Ahmad Mola Nissi: Arab nationalist from Iran shot dead in Netherlands”, The Independent, 9 November 2017, accessed via: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/ahmad-mola-nissi-dead-shot-netherlands-iran-arab-nationalist-a8046646.html. | The Hague, Netherlands | Ahmad Mola Nissi | Dissident |

Iran’s intelligence services and the IRGC Quds Force have a global presence. Iran’s intelligence activity connects Iran with terrorist groups and organised criminal syndicates. Iranian intelligence has two objectives. First, Iran intimidates, kidnaps, and assassinates Iranian dissidents.56“Timeline: Iran’s assassinations and plots to kill dissidents living abroad”, Al-Arabiya English, 16 July 2021, accessed via: https://english.alarabiya.net/features/2021/07/16/Timeline-Iran-s-assassinations-and-plots-to-kill-dissidents-living-abroad. The IRGC has conducted operations on British and American soil, within the EU, and throughout the Middle East. MI5 Director-General Ken McCallum, in his 2022 threat assessment, notably identified Iran as behind at least ten plots against British citizens and UK-based dissidents.57Ken McCallum, “Annual Threat Update”, MI5, 16 November 2022, accessed via: https://www.mi5.gov.uk/news/director-general-ken-mccallum-gives-annual-threat-update. In 2011, the U.S. FBI foiled an Iranian plot to assassinate the Saudi Ambassador and attack the Saudi and Israeli embassies.58“Two Men Charged in Alleged Plot to Assassinate Saudi Arabian Ambassador to the United States”, U.S. Department of Justice, 11 October 2011, accessed via: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-men-charged-alleged-plot-assassinate-saudi-arabian-ambassador-united-states. Iranian intelligence also has an extensive European presence. According to Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service, the BND, 160 active Iranian agents have been with German connections, primarily engaged in operations against Jewish groups.59Frederik Schindler, “Iran betreibt „umfangreiche Ausspähungsaktivitäten“ in Deutschland”, Welt am Sonntag, 11 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article243710081/Iran-betreibt-umfangreiche-Ausspaehungsaktivitaeten-in-Deutschland.html. Iranian agents are also active in the Netherlands. AIVD, the Netherlands’ intelligence agency, identified Iranian participation in two assassinations of regime dissidents in the 2010s.60“Iran likely involved in assassinations in the Netherlands”, AVID, 8 January 2019, accessed via: https://english.aivd.nl/latest/news/2019/01/08/iran-likely-involved-in-assassinations-in-the-netherlands.

In 2022, the IRGC likely organised the Salman Rushdie Assassination Attempt, during which Hadi Matar, with known sympathies towards the IRGC and Hezbollah.61James Phillips, “Was Iran Behind Attempt to Kill Salman Rushdie in America?” Heritage, 18 August 2022, accessed via: https://www.heritage.org/terrorism/commentary/was-iran-behind-attempt-kill-salman-rushdie-america. The world-renowned British-American novelist has had a price on his head since Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for his execution in 1989.62“Part 1: Khomeini’s Fatwa on Rushdie”, The Wilson Center, 16 August 2022, accessed via: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/part-1-khomeinis-fatwa-rushdie. Iranian intelligence is extraordinarily persistent. This January, FBI Director Christopher Wray announced that U.S. law enforcement had stopped a second plot against an Iranian dissident journalist in the New York City area.63Christopher Wray, “Director Christopher Wray’s Remarks at Press Conference Announcing Charges and New Arrest in Connection with Assassination Plot Directed from Iran” FBI, 27 January 2023, accessed via: https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/director-christopher-wrays-remarks-at-press-conference-announcing-charges-and-new-arrest-in-connection-with-assassination-plot-directed-from-iran. Although the target’s name is unconfirmed, it is almost certainly Mahsa Alinejad, an Iranian-born journalist whose high-profile criticisms of the regime have drawn the Iranian state’s ire, and who Iranian intelligence previously sought to assassinate in 2021.64“Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Kidnapping Conspiracy Charges Against An Iranian Intelligence Officer And Members Of An Iranian Intelligence Network”, Department of Justice, 13 July 2021, accessed via: https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-announces-kidnapping-conspiracy-charges-against-iranian.

Iranian intelligence also targets dissident Iranian media outlets. Iran International, founded in 2017, has become the premier opposition news network in the Persian speaking world.65Reformist-inclined Iranian media even engage with Iran International, which now may be the most viewed media outlet in Iran. See https://www.sharghdaily.com/%D8%A8%D8%AE%D8%B4-%DA%AF%D9%88%DB%8C%D8%B4-231/852640-%D8%B1%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%87-%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%82%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%A8%DB%8C-%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%87-%D9%BE%DB%8C%D8%B4-%D8%B1%D9%88. In February 2023, Iran International announced that it will transfer operations from London to Washington, DC given pervasive IRGC security threats against its staff.66George Wright, “Iran International: Channel leaves UK after regime threats”, BBC, 18 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-64690387. Iranian intelligence, then, not only targets dissidents in general, but also is tasked with breaking up dissident information networks that can threaten the Iranian regime.

Beyond its intimidation of and attacks on dissidents and regime opponents, Iran uses its international intelligence presence to facilitate its links to the global black market.67Under the Shadow: Illicit Economies in Iran (The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, October 2020), 3-8. The IRGC and bonyad system – which is in turn IRGC controlled – interfaces between the Afghan drug trade and international markets. Iranian agents, either directly or through Hezbollah, then work with Latin American drug cartels and Euro-American gangs.68Aurora Ortega, “Hezbollah in Colombia: Past and Present Modus Operandi and the Need for Greater Scrutiny”, Washington Institute, 28 March 2022, accessed via: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/hezbollah-colombia-past-and-present-modus-operandi-and-need-greater-scrutiny. See also Ali Hajizade, “How the Iranian regime allows drug trafficking for foreign currency liquidity”, Al-Arabiya English, last updated 20 May 2020, accessed via: https://english.alarabiya.net/features/2018/08/16/How-the-Iranian-regime-allows-drug-trafficking-for-foreign-currency-liquidity-. Venezuela is Iran’s primary conduit to Latin America. Hugo Chavez and his successor Nicolas Maduro progressively turned to the drug trade to ensure state finances.69Roger F. Noriega, Kirsten D. Madison, et. al., Kingpins and Corruption: Targeting Transnational Organized Crime in the Americas (American Enterprise Institute, July 2017), 18-31. Iran, through a variety of shell companies, works through Venezuela to ensure Latin American drug access.70“Advisory on the Iranian Regime’s Illicit and Malign Activities and Attempts to Exploit the Financial System”, U.S. Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network Advisory (FIN-2018-A006, 11 OCTOBER 2018). It also has connections with Mexican cartels, most notably Los Zetas.71Jo Tuckman, “Iran’s alleged Mexican hitman was US drugs informant”, The Guardian, 12 October 2011, accessed via: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/12/iran-mexico-drug-informant-hitman. Iranian groups also have European links, most notably to Anglo-Irish organised crime through the Kinahan Gang, which has laundered money for Hezbollah, and the New IRA, whose relationship with Hezbollah was facilitated by the Iranian embassy in Ireland.72John Mooney, “New IRA forges links with Hezbollah”, 13 September 2020, accessed via: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/new-ira-forges-links-with-hezbollah-gq68x8w5w.

Iran employs its illicit financial connections and links to criminal organisations to evade sanctions and export illegal oil.73Srinivas Mazumdaru and Nik Martin, “How Iran is boosting oil exports despite US sanctions”, DW, 1 February 2023: https://www.dw.com/en/how-iran-is-boosting-oil-exports-despite-us-sanctions/a-64562167. Iran has perfected its Dark Tanker methods over the past decade, using incorrectly-registered ships with their transponders turned off and shipping oil through Kuwait to evade detection.74Michael Lipin, “Tanker Trackers: After Iraqi Oil Blending Scheme, Iran Found Better way to Evade US Sanctions”, Voice of America, 18 August 2022, accessed via: https://www.voanews.com/a/tanker-trackers-iran-ditched-iraqi-oil-blending-scheme-for-better-way-to-evade-us-sanctions/6707265.html; “Treasury Sanctions Oil Shipping Network Supporting IRGC-QF and Hizballah”, U.S. Department of the Treasury, 3 November 2022, accessed via: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1076. Iranian oil exports probably grew by 35% in 2022 despite Western sanctions.75Michael Lipin, “Q&A: Iran Likely Grew Oil Exports by 35% in 2022, Data Company Says”, Voice of America, 18 January 2023, accessed via: https://www.voanews.com/a/q-a-iran-likely-grew-oil-exports-by-35-in-2022-data-company-says-/6924648.html.

Finally, Iran poses a direct threat to British social cohesion. Iran has a network of active agents and friendly plants within the UK that it has used, and will employ in the future, to infiltrate British society. Iranian influence networks overlap with, but are distinct from, its intelligence activities in the UK. Iran works through religious and social organisations. Iranian influence operations seldom target Shia causes, given that only five percent of British Muslims are Shia.76“Estimated Percentage Range of Shia By Country”, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life: Mapping the Global Muslim Population, accessed via: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2009/10/Shiarange.pdf. At most, 15% of British Muslims are Shia. Mosque data is even more heavily skewed towards Sunnism: there are far fewer Shia Islamic centres and Mosques than Sunni locations. Instead, Iran creates pan-Islamic organisations for its own ends, like the Maida Vale Islamic Centre of England, which has Iran’s Supreme Leader serve as one of its trustees.77Camilla Turner, “Home Office accused of failing to close Iran’s ‘London office’,” The Telegraph, 11 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2023/02/11/home-office-accused-failing-close-irans-london-stronghold/.

British Sunni Muslim organisations generally ignore Iranian domestic brutality and its viciousness in Syria and Iraq, instead focusing on anti-Western and anti-Israel causes. This affords Iran significant operational space, as it can generate support for its causes without marking itself as Shia in a British context. Iranian networks have staged rallies in support of Iran’s Iraqi proxies, including Kataib Hezbollah, which has killed British soldiers in the Middle East during the Iraq War.78See “London Rally in Support of the Militant Group Hashd al-Sha’bi”, Policy Exchange, 28 November 2020, accessed via: https://policyexchange.org.uk/blogs/london-rally-in-support-of-the-militant-group-hashd-al-shabi/.

Iran’s Islamic organisations in the UK have also influenced British electoral politics, most recently courting former Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon in 2019.79Struan Stevenson, “How Nicola Sturgeon narrowly avoided handing propadanda coup to brutal Iran”, The Scotsman, 21 November 2019, accessed via: https://www.scotsman.com/news/opinion/columnists/how-nicola-sturgeon-narrowly-avoided-handing-propadanda-coup-brutal-iran-struan-stevenson-1401756. Indeed, Iranian influence on the SNP runs deep. In 2015, former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond led a formal trade delegation to Iran.80Jamie Brotherston, “SNP delegation to Iran highlights Scotland’s potential to create foreign policy initiatives”, The Herald, 23 December 2015, accessed via: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/14168707.snp-delegation-iran-highlights-scotlands-potentialcreate-foreign-policy-initiatives/. A number of SNP officials are linked to Iranian agents, including East Kilbride Councillor Ali Salamati – moreover, the Iranian-linked charity Ahl al-Bayt has received significant donations from the Scottish government.81Jake Wallice Simons, “Sturgeon’s link to anti-gay Iran cleric“, The Jewish Chronicle, 10 March 2021, accessed via: https://www.thejc.com/news/uk/sturgeon-s-link-to-anti-gay-iran-cleric-1.512738. Iranian social media and cyber capabilities amplify Iranian manipulation. Iran has sought to use astroturfed social media accounts in the past to support Scottish separatism, doing so during the previous Scottish Independence Referendum and during other Scottish elections.82Jack Aitchison, “Scottish independence debate targeted by Iran-based fake social media accounts”, The Herald Scotland, 22 January 2022, accessed via: https://www.heraldscotland.com/politics/19867365.scottish-independence-debate-targeted-iran-based-fake-social-media-accounts/. If the SNP execute a Catalan-style illegal referendum, their effort will receive Iranian support. Nicola Sturgeon’s exit as SNP Leader and Scottish First Minister may increase the possibility of pro-Iranian penetration. As of this writing, Humza Yousaf, currently second in polling for SNP Leader, has historical connections to Islamist-sympathetic groups.83Alongside his cousin Osama Saeed, Yousaf ran the Scottish islamic Foundation in the 2000s. The SIF was subsequently identified as a potential Islamist affiliate, and Saeed was ultimately dropped as an SNP candidate. See Angus Macleod, “SNP urged to drop ‘sectarian and divisive’ Muslim candidate”, The Times, 23 April 2009, accessed via: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/snp-urged-to-drop-sectarian-and-divisive-muslim-candidate-gq8f6z62xjf. Although he has no direct connections to Iran, a Yousaf win would ease the task of Iranian social media operatives seeking to encourage broader Muslim support for Scottish separatism.

The Evolving Threat: Iranian Strategic Expansion in the 2010s

In the 2010s, Iran shifted from a defensive strategic posture to an expansionist one. Its ambitions grew from solidifying its position in neighbouring states to building a corridor through the Levant and to the Eastern Mediterranean, along with a flanking manoeuvre around the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen. This expansion gave Iran access to, and the potential control, the Suez-Indian ocean maritime chokepoint, generating a long-term threat to regional stability. Notably, U.S. intelligence assessed that, to quote former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper: “Iran’s Supreme Leader continues to view the United States as a major threat. We assess that his views will not change despite the implementation of the JCPOA deal”.84James R Clapper, “Senate Armed Services Committee Hearing – IC’s Worldwide Threat Assessment: Opening Statement”, Dirkson Senate Office Building, Washington DC (9 February 2016), 5. The Iran deal, therefore, made little difference to Tehran’s strategic calculations.

Iran intervened in Syria as the anti-Assad protests transitioned to a full-blown civil war. The Syrian Arab Army suffered from poor training and morale, alongside a spate of defections.85Will Fulton, Joseph Holliday, and Sam Wyer, Iranian Strategy in Syria (AEI Critical Threats Project & the Institute for the Study of War, May 2013), 9-10. Assad quickly lost ground to the FSA and other rebel groups. Iran’s intervention in Syria was alone insufficient to deliver victory to Assad – it took Russia’s subsequent, open intervention to tip the scales in 2015-2018. However, Lebanese Hezbollah became a crucial ground force for the Assad regime, giving the SAA time to reconsolidate. IRGC Quds Force officers, including Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, also directed multiple offensives that broke rebel momentum, staving off Assad’s collapse in 2012-2013. Moreover, while Russia provided aircraft, ammunition, and other materiel to the SAA, Iranian intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance sustained Syrian combat capacity.

Russia’s 2015 intervention, the tide turned decisively in Assad’s favour. Concurrently, Iran signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reducing sanctions pressure and opening up Iranian cashflow.86Lindsey Graham and Morgan D Ortagus, “Biden’s $90 Billion Bailout to Tehran”, Foreign Policy, 28 April 2021, accessed via: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/28/iran-deal-biden-bailout/. See also Emma Borden, “The United States, Iran, and $1.7 billion: Sorting out the details”, Brookings, 3 October 2016, accessed via: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/10/03/the-united-states-iran-and-1-7-billion-sorting-out-the-details/. Moreover, the Iraqi military’s near-collapse in 2014 against IS’ initial offensives, while placing additional strain upon the IRGC, did ultimately allow Iranian-backed Shia militias in Iraq to gain a far greater political position in the Iraqi security services.87Hamdi Maliki, “The Future of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 21 September 2017, accessed via: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/73186. New cashflow enabled another proxy intervention, in Yemen, in support of the Houthi Movement.88Seth G. Jones, Jared Thompson, Danielle Ngo, Brian McSorley, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “The Iranian and Houthi War against Saudi Arabia”, CSIS Briefs (December 2021), 4-7. This has provided Iran with a foothold at the Suez-Indian Ocean route’s southern exit.

Compared to 20 years ago, the erosion of Western power in the Middle East has created a regional strategic situation strongly favours Iran. Iran has a continuous supply route to Lebanon through Iraq and Syria, along with political leverage, if not political control, over both states. Iran thus brackets the Suez-Indian Ocean route, through which a third of global container shipping volumes transit, and is within striking distance of Gulf State oil refineries.89Joe Myers, “The Suez Canal in numbers”, WEF, 25 March 2021, accessed via: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/03/the-suez-canal-in-numbers/. Moreover, it has settled its ideological dispute with the Palestinian terrorist movement, becoming Hamas’ primary benefactor, and sustaining Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Iran thereby brackets Israel and Jordan.90“Treasury Targets Facilitators Moving Millions to HAMAS in Gaza”, U.S. Department of the Treasury, 29 August 2019, accessed via: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm761. Iran Military Power Report (Defense Intelligence Agency, 2019),62-63.

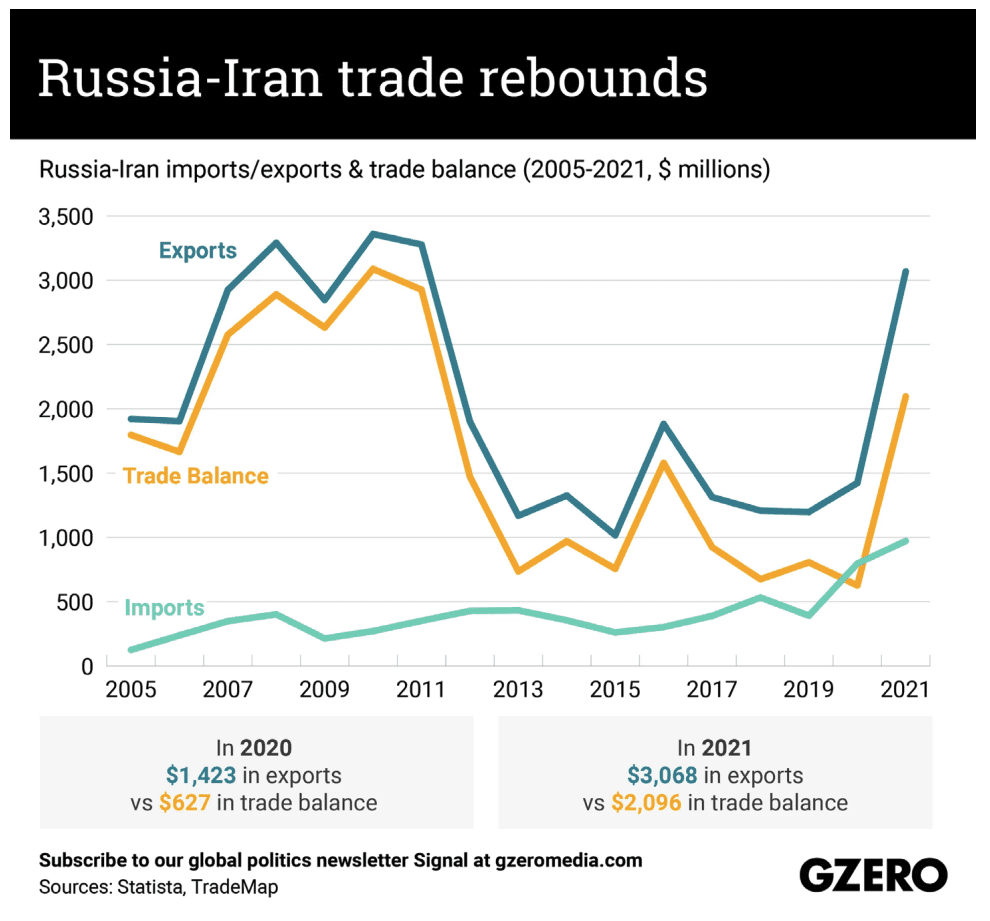

Iran and Russia

Iranian regional expansion intensified its relationship with Russia, the acute military threat the UK faces. Iran’s partnership with Russia stems from the 1990s – despite Russian pledges to the contrary, the Kremlin assisted Iran with its nascent ballistic missile programme from 1995 onwards.91Fred Wehling, “Russian Nuclear and Missile Exports to Iran”, The Nonproliferation Review, 6:2 (Winter 1999), 134-136. However, this partnership intensified in the 2010s during the Arab Spring. Russia sold Iran advanced military material, notably the S-300 air defence system,92April Brady, “Russia Completes S-300 Delivery to Iran”, Arms Control Today, December 2016, accessed via: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2016-11/news-briefs/russia-completes-s-300-delivery-iran. and Iran offered Russia basing rights.93Dmitry Trenin, “Russia and Iran: Historic Mistrust and Contemporary Partnership”, Carnegie Moscow, 18 August 2016, accessed via: https://carnegiemoscow.org/2016/08/18/russia-and-iran-historic-mistrust-and-contemporary-partnership-pub-64365. Iran’s Caspian maritime link with Russia increases avenues for Russo-Iranian trade, and Iran is a long-time Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) aspirant.94The CSTO is Russia’s de facto answer to NATO, meant to provide Russia with strategic control in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

FIGURE 4: RUSSIA-IRAN TRADE

Figure 4: Russia-Iran Trade since 2005, accessed via: https://www.gzeromedia.com/the-graphic-truth-russia-iran-trade-rebounds

Iran has capitalised upon the Ukraine War to gain strategic leverage over Russia and undermine the latitude the Kremlin has in the Middle East. As it stands, Iran is Russia’s most public ally in Ukraine – compared to Belarus, which since 2020 has been increasingly drawn into Russia’s orbit, Iran’s choice to support Russia openly with military equipment is far more consequential.95Claire Mills, “Belarus: One year on from the disputed Presidential election”, House of Commons Library (Report Number 9344, 5 October 2021), 14-18; see also Nigel Walker and Tim Robinson, “Belarus: 2020 presidential election”, House of Commons Library (Briefing Paper CBP 8979, 8 September 2020), 8. Iran has provided Russia with both economic and military support. Economically, Iran has the world’s most robust sanctions-evasion networks, cultivated over decades. Of particular interest is Iran’s ability to export petrochemicals through its dark tanker fleet and various shell organisations. This ability sustained Russian revenues, and there is considerable evidence of Iranian assistance.96Matthew Karnitschnig, “Iran teaches Russia its tricks on beating oil sanctions”, Politico, 9 November 2022, accessed via: https://www.politico.eu/article/iran-russia-cooperation-dodging-oil-sanctions/. Iran and Russia have signalled their intention to expand the trans-Caspian route, formalising their new trade relationship. Russia will finance a major extension that improves the link between Bandar Anzali, Iran’s major Caspian Sea port, to Rasht, which is linked directly to the North-South Transport Corridor that runs from Moscow to Mumbai.97Nikos Papatolios, “Russia to develop transport hub in Iran, rail investments on the agenda”, RailFreight, 11 October 2022. accessed via: https://www.railfreight.com/corridors/2022/10/11/russia-to-develop-transport-hub-in-iran-rail-investments-on-the-agenda/. Russia has also invested in its major Caspian ports and expanded the navigable canals between the Azov Sea and the Volga, increasing trade potential.98Chris Devonshire-Ellis, “BREAKING: Putin’s Speech To The Russian General Assembly – The 2023 Trade & Commerce Content”, Russia Briefing, 21 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.russia-briefing.com/news/breaking-putin-s-speech-to-the-russian-general-assembly-the-2023-trade-commerce-content.html/; see also “Russia Invests in Volga-Don Canal as Trade With Iran Booms”, The Maritime Executive, 21 December 2022, accessed via: https://maritime-executive.com/article/russia-invests-in-volga-don-canal-as-trade-with-iran-booms. Moreover, Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, Iran’s state-owned shipping company under U.S. sanctions and formerly under EU and UN sanctions, increased its Caspian Sea activity in 2022.99See the following from the Financial Tribune, an Iranian-domiciled paper, “IRISL Cargo Shipment Hit Record High of 27m Tons in Fiscal 2021-22”, 8 July 2022, accessed via: https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/irisl-cargo-shipment-hit-record-high-of-27m-tons-in-fiscal-2021-22/; see also “Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL)”, Iran Watch, last updated 26 June 2020, accessed via: https://www.iranwatch.org/iranian-entities/islamic-republic-iran-shipping-lines-irisl. All this points to a greatly increased Iran-Russia economic relationship.

Militarily, Iran’s diverse drone and loitering munition fleet has become integral to Russian strategy. Russia uses Iranian loitering munitions to bombard Ukrainian infrastructure and civilians, while Iran’s small and medium size UAS are crucial for Russian battlespace awareness.100“Iranian UAVs in Ukraine: A Visual Comparison”, U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, 14 February 2023, accessed via: https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23613688/dia_iranian_uavs_in_ukraine-a_visual_comparison.pdf. Iran has deployed technical advisors, likely from the IRGC Quds Force, to train Russian operators in Crimea.101Julian Borger, “Iranian advisers killed aiding Russians in Crimea, says Kyiv”, The Guardian, 24 November 2022, accessed via: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/24/iranian-military-advisers-killed-aiding-moscow-in-crimea-kyiv. Iran has also provided Russia with 300,000 artillery shells and one million ammunition rounds since November 2022, ferrying supplies directly to Russia over the Caspian.102Dion Nissenbaum and Benoit Faucon, “Iran Ships Ammunition to Russia by Caspian Sea to Aid Invasion of Ukraine”, Wall Street Journal, 24 April 2023, accessed via: https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-ships-ammunition-to-russia-by-caspian-sea-to-aid-invasion-of-ukraine-e74e8585.

Absent Iranian military and economic support, Russia’s war effort in Ukraine may have collapsed. Russia burned through its precision-guided munitions stockpiles by mid-2022, and faced a missile shortage even as it began its strategic strike campaign.103John Hardee, “Estimating Russia’s Kh-101 Production Capacity”, Long War Journal, 16 December 2022, accessed via: https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2022/12/estimating-russias-kh-101-production-capacity.php. After its major strike waves in December 2022, Russia struggled to sustain its bombardment of Ukrainian infrastructure. Iran’s loitering munitions have relatively small warheads.104Uzi Rubin, “Russia’s Iranian-Made UAVs: A Technical Profile”, RUSI, 13 January 2023, accessed via: https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-iranian-made-uavs-technical-profile/. But they are cheap, easy to construct, and can be launched from a modified civilian trailer bed.105Ibid. Even absent ballistic missile transfers to Russia, then, Iran has played a crucial role in the Russian war effort, as critical as Belarus.106Pavel Slunkin, “Putin’s last ally: Why the Belarusian army cannot help Russia in Ukraine”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 27 October 2022, accessed via: https://ecfr.eu/article/putins-last-ally-why-the-belarusian-army-cannot-help-russia-in-ukraine/.

Iran’s support for Russia in Ukraine demonstrates the degree to which its hostility towards the West is fundamental and difficult to reverse. Iran’s support for Russia does provide benefits. But Iran could well have allowed Russia to persist without transferring it significant quantities of military equipment, and instead providing it with only economic and commercial support. The fact that Iran has engaged actively in the Ukraine War indicates the degree to which Tehran has bet on a systemic transformation throughout Eurasia, including in Europe. An impulse so deeply ingrained in Iranian strategy will not be dislodged by a negotiated agreement over Iran’s nuclear programme.

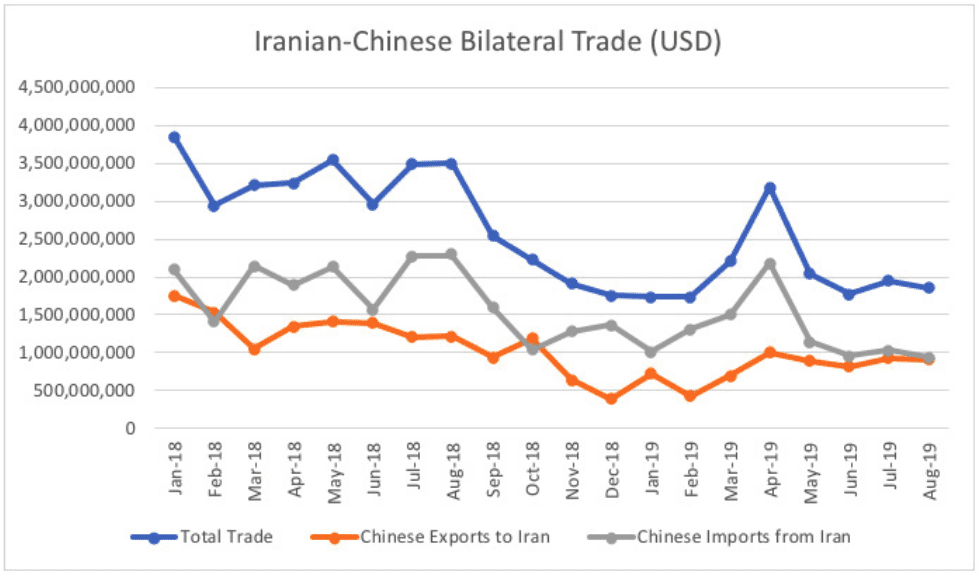

Iran and China

Iran’s relationship with China is less public but equally relevant. Sino-Iranian relations have been vital for Tehran. Chinese consumer electronics, automobiles, and other manufactured goods have reduced Western sanctions pressure.107“China-Iran Profile”, OEC, last updated December 2022, accessed via: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/irn. Iran is also a long-standing petrochemical exporter to China, not as critical as the Gulf States, but still relevant for Chinese energy security. As Sino-American tensions increase, Iran can spoil the theorised American “far blockade” that cuts off Chinese oil and gas imports from U.S. positions in the Middle East, strangling the Chinese economy during an Indo-Pacific War. There is no guarantee that Iran would be a co-belligerent; but Iran’s strategic importance to China is only likely to increase as friction with the U.S. grows.108Kathrin Hille and Najmeh Bozorgmehr, “Xi Jinping vows to boost Iran trade and help revive nuclear deal”, Financial Times, 14 February 2023, accessed via: https://www.ft.com/content/568edcd3-f189-4c62-8b2a-c5878c524ada. The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA made the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Sino-Russian political organisation, a lifeline for the Iranian economy.109Umud Shokri, “Iran and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 16 November 2022, accessed via: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/88427. Tehran obviously views the SCO as a safety valve against Western sanctions – in June 2022, Iran proposed a single SCO currency, which would allow a Russia-China-Iran grouping to evade Western sanctions.110“Deputy FM: Iran proposes single SCO currency”, Islamic Republic News Agency, 2 June 2022, accessed via: https://en.irna.ir/news/84775351/Deputy-FM-Iran-proposes-single-SCO-currency.

FIGURE 5: CHINA-IRAN TRADE

Figure 5: China-Iran Bilateral Trade, accessed via: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/despite-sanctions-china-is-still-doing-some-business-with-iran/