Authors

Content

Executive Summary

Thirty years ago, the British and Irish governments issued the Downing Street Declaration, which asserted that the UK has no “selfish strategic” interest in Northern Ireland. The Declaration was one of the key building blocks in the Northern Ireland peace process, leading to the ceasefire in 1994 with the IRA and, ultimately, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. As part of the peace process, the UK drew down its remaining active military presence in Northern Ireland, concluding Operation Banner in 2007.

No ‘selfish strategic’ interest does not, however, mean no ‘strategic’ interest. The political unity of the Union dictates that, by definition, Northern Irish and British strategic interests are one and the same. The UK therefore cannot have selfish interests in Northern Ireland, but its strategic interests are inviolable.

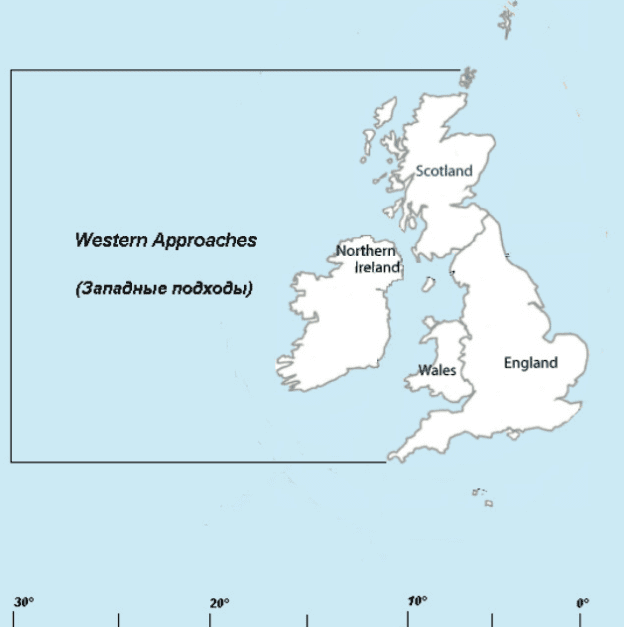

Although reducing the Army presence was central to the peace process, it was the closure of RAF and Royal Navy bases – a gradual process initiated after 1945 – which significantly weakened the UK’s strategic position in Northern Ireland. Without a naval and air forward presence to the left of the Irish Sea, the UK’s capacity to police the Western Approaches, and deploy further towards the Greenland- Iceland-UK (GIUK), is limited. This poses direct challenges to the whole British defensive system.

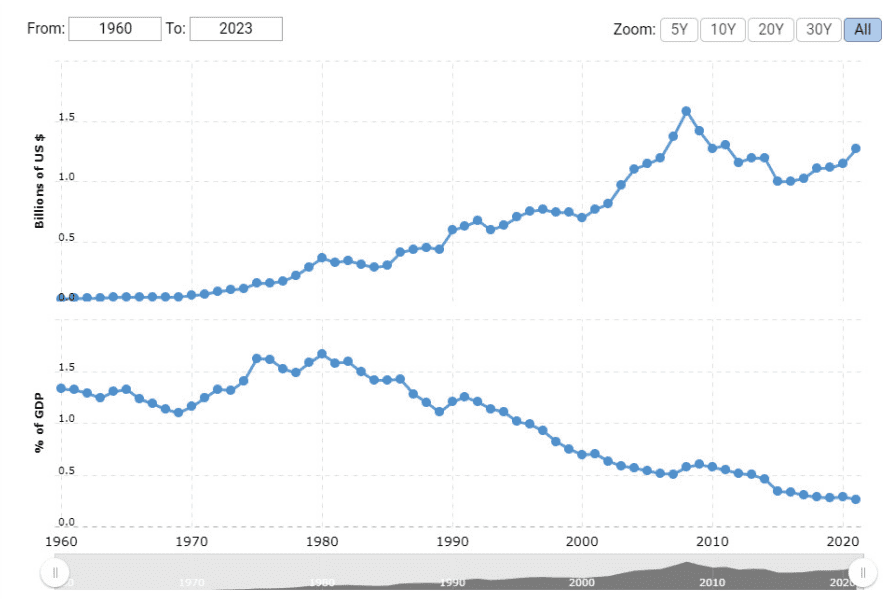

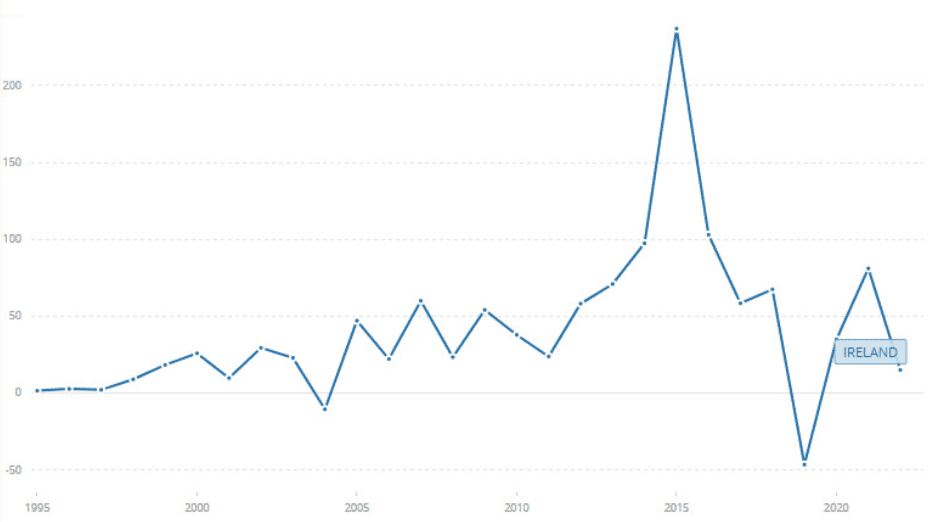

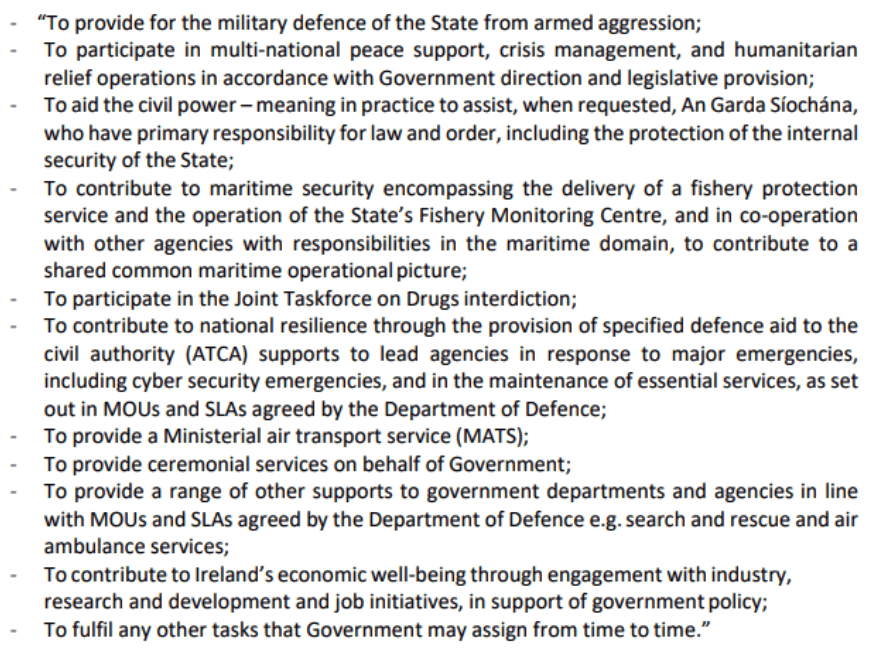

The Republic of Ireland’s (ROI) avowed neutrality, chronically insufficient Defence Forces, and porous security state render it an unreliable strategic ally. The UK’s northwestern exposure is compounded by the lack of assistance from the ROI. For decades, Irish defence spending has fallen well below 1% of GDP, producing a Defence Forces which is under-equipped, under-sized and under-staffed. In any case, commitment to its policy of neutrality precludes the ROI from engaging seriously with the UK on security issues, either bilaterally or as part of NATO.

In an age of growing geopolitical threats, this gap in the UK’s northwestern defences now directly endangers its national security. Negotiated amidst intractable political violence in Ireland, and in the post-Cold War period of relative peace, the full implications of the military draw-down in Northern Ireland were concealed. The return of an aggressive Russia, actively waging war in Europe, has placed renewed strategic importance on the UK’s north and northwestern flanks.

As Russia’s maritime doctrine shifted in 2022 to prioritise the Arctic and Atlantic, it is incumbent upon the UK to fortify its northwestern naval and air patrol presence. Major transatlantic undersea fibre-optic cables run through the Western Approaches, upon which the digital security of the UK and its partners – including the ROI – depend. Meanwhile, Russia has advanced its sub-surface capabilities and – as the recent uptick in reported sightings illustrates – is exploring ways to target western critical undersea infrastructure around the UK, and further north. To coordinate our collective response with our partners, we must respond in turn with a greater Royal Navy and RAF presence in the region.

As well as proving a menace in the maritime domain, Russia – alongside China and Iran – seeks to degrade the UK and its allies through unconventional means. Cyber warfare, institutional espionage, and educational and economic infiltration are all subthreshold methods employed by these authoritarian regimes to destabilise the West.

The combination of ROI’s flimsy security and intelligence apparatus, unwillingness to acknowledge these threats, and soft border with Northern Ireland poses a grave back-door security risk to the UK. Adversaries are certain to target the ROI, due to its close integration into transatlantic economic and digital systems, membership of the EU, and self-imposed exclusion from multilateral security frameworks. There is already strong evidence of a subversive and illegal Russian, Chinese and Iranian presence across Irish society and sensitive institutions.

Although the ROI has embarked on a reform of its Defence Forces and security apparatus in recent years, the outcome is destined to fall short of requirements, due to a persistent lack of financial and political commitment. The entire Defence Forces, and security and intelligence apparatus, is being built almost from scratch. With defence spending to increase by only 50% by 2028, and the stubborn shibboleth of neutrality still acting as a brake on ambition, the ROI is not set to become a capable security partner any time soon.

As it stands, Sinn Féin is expected to win the ROI’s next election in 2025, a party which will be no friend to British interests. Sinn Féin’s long history of Anglophobia, and conflict with the British state and security services – as well as its opposition to NATO, Russian sympathies, and general anti-Western sympathies – will obstruct any meaningful recalibration of security arrangements with the UK. If Sinn Féin wins in 2025, the UK is therefore looking at many more years of an uncooperative, and likely hostile, neighbour in the face of growing external threats.

Northern Ireland is therefore the key to addressing the UK’s security concerns. Resurrecting the RAF and Royal Navy presence in Northern Ireland will bolster our forward presence for maritime patrol operations around our coastline, as well as into the GIUK Gap and beyond. In light of Russian aggression, recent government strategic documents have flagged our stretched naval and air capabilities in the north. Northern Ireland can therefore strengthen our strategic options in the region, whilst alleviating the burden on other bases, such as HMNB Clyde and RAF Lossiemouth.

Shifting the paradigm of British-Irish relations – by breaking the longstanding link between a British Northern Ireland military presence, and Ireland’s historically fraught past – will enable the UK to create the environment for an equitable and effective security relationship between the ROI and the UK. The ROI is at severe risk of being compromised from within by hostile actors, perils which were illustrated by the massive Russian cyber-attack on the Irish health service in 2021. Geographical proximity, and the soft border, mean that Irish vulnerabilities are British vulnerabilities. Having signalled its renewed strategic focus on Northern Ireland, the UK can make known its interests – and willingness to assist, in an equitable manner – in the ROI’s security problems.

Next chapterForeword

By Rt Hon Sir Michael Fallon KCB, former UK Secretary of State for Defence, and Rt Hon Lord Robertson of Port Ellen KT, former Secretary General of NATO and former Secretary of State for Defence

Policy Exchange has a record of bringing neglected topics of national importance to the fore. British-Irish security is one such issue.

As Defence Secretaries in different governments at different times, we know that little attention was paid to the security of the island of Ireland in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War.

We therefore welcome this new report from Policy Exchange, which powerfully reasserts the strategic importance of Ireland, and especially Northern Ireland, to the UK’s national security.

Re-setting the importance of the Western Approaches is all the more urgent in the sharpening Euro-Atlantic geopolitical climate. Russia poses an acute maritime menace to both our countries as it targets the undersea fibre-optic cables, pipelines and interconnectors which underpin our critical digital and energy systems.

Russian intelligence ships and warships have been identified off the Irish coast and close to key transatlantic cables. The growing Russian, Iranian and Chinese presence in the Republic poses a backdoor threat to the United Kingdom itself.

European security is also vulnerable. Threequarters of the most critical Atlantic cables pass through or close to Ireland’s borders; the Republic hosts a third of Europe’s data companies. As an EU member and a hub of the international financial and technology sectors Ireland is an attractive target for those who might want to attack our economic and political systems: already we have seen cyber and pipeline attacks in the Baltic and on Europe’s eastern frontier.

Ireland is now finally reviewing its defence posture. Sweden and Finland have already decided that neutrality is no longer sustainable against Russian aggression.

The Republic plays very little part in European defence co-operation; its forces, especially maritime, need rapid strengthening to be capable of defending against today’s threats.

The UK should certainly encourage this, building on the initial UK-Ireland Defence Agreement signed in 2015. But the current threats to our own security are growing and urgent. What the government should do immediately is to rediscover the vital strategic importance of Northern Ireland, and fortify this weak spot in our own security.

Next chapterIntroduction

Thirty years ago, the British and Irish governments issued the Downing Street Declaration. In the Declaration, then Prime Minister John Major asserted that the British government has “no selfish strategic” interest in Northern Ireland,1Irish Department of Foreign Affairs, Joint Declaration 1993 (Downing St. Declaration), 15 December 1993, 1, https://www.dfa.ie/media/dfa/alldfawebsitemedia/ourrolesandpolicies/northernireland/peace-process–joint-declaration-1993.pdf. an excerpt borrowed from a speech made in 1990 by Northern Ireland Secretary, Peter Brooke. Over the ensuing years, the UK acted accordingly, finalising the military withdrawal from Northern Ireland by 2007.2Adam Payne, Northern Ireland: in the balance, Politics Home, 29 June 2021, https://www.politicshome.com/thehouse/article/northern-ireland-in-the-balance#:~:text=The%20army%20officially%20withdrew%20from,in%20more%20than%203%2C500%20deaths. The UK was eventually left with its smallest military force on the island of Ireland in modern history. The Declaration laid the groundwork for the Good Friday Agreement five years later, bringing to an end the bloody 30-year period of the Troubles. Few would argue that this was an unworthy cause.

In many ways, the Declaration was a masterful example of strategic ambiguity, designed so as simultaneously to attenuate nationalist concerns over British imperialistic motivations in Northern Ireland, and to enshrine the political unity of the UK.

However, the British military draw-down which ensued was in fact based on a fundamental misinterpretation of the Declaration. Grammar matters after all, even down to a comma. No selfish strategic interest does not mean no strategic interest. In fact, the UK quite obviously has a strategic interest in Northern Ireland by territorial definition, and per the contours of geopolitical rivalry.

That these interests are unselfish speaks to the essence of the Union – that the interests of the island of Great Britain and the territories of Northern Ireland are indissolubly intertwined. Furthermore, as has been demonstrated throughout the course of history, the security of the British Isles as a whole converges in the face of external threats. Thus – whether through lack of attention to detail, or the desire to bring an end to political unrest despite long term costs – the total withdrawal of our strategic forward presence on the western side of the Irish sea has weakened the Union strategically and politically.

Whilst the peaceful post-Cold War years hid the implications of this decision, the return of major conflict to Europe has unearthed the deteriorating security environment the UK now faces. Two factors interact to generate this environment: a neighbour in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) which is uncooperative from a security perspective towards the Union and its partners; and the lack of British forward presence in Northern Ireland, which would otherwise go some ways towards compensating for Irish intransigence. Today, Russia’s war on Ukraine, China’s determination to challenge the US-led world order, and subversive Iranian activity across Europe all combine to form the most serious threat landscape that the UK has faced since 1991 at least. In this context, the island of Ireland constitutes the weak spot of British national security. This paper argues that only a paradigm shift in security arrangements on the island of Ireland can remedy this situation.

The ROI has consistently refused to contribute sufficiently to the collective security it shares with its partners. Despite the ROI’s crucial position at the transatlantic gateway to Europe, persistent under-investment in the military and security instruments has left it unable to protect itself at sea, by air, and from cyber and subversive infiltration. Whilst the UK and the ROI both play crucial roles in the flow of goods, capital and digital information which powers western prosperity and security in the 21st century, the contrast in their respective commitment to defending these systems is stark.

Partly as a response to the new geopolitical environment, the ROI has embarked upon a reform of its military and security apparatus. By 2028, the government aims to restructure and bolster the Irish Defence Forces and security apparatus to respond better to the full array of the modern threat landscape. As part of the process, defence spending is on a slow trajectory towards a 50% increase between 2022 and 2028.3Irish Government, Government announces move to transform the Defence Forces and the largest increase in the Defence budget in the history of the State, 13 July 2022, https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/b3c91-government-transform-defence-forces-largest-increase-defence-budget-in-history-of-state/.

However, the task of building a national security system from near-scratch, paired with budgetary constraints and a political culture fundamentally opposed to serious strategic thought, breeds pessimism regarding the prospects of enhanced ROI security any time soon. As a result, it will continue to be a critical weak point across the Atlantic and within Europe. With polls predicting a Sinn Féin victory in the next general election, Irish security engagement with the UK and transatlantic alliance is likely to be jeopardised until the end of the decade. Sinn Féin’s enduring Anglophobia, and ambivalence towards transatlantic and European security, means that an Irish government it leads will be no friend to British strategic interests.

This paper therefore calls upon the UK to rediscover its strategic interests in Northern Ireland, in order to improve the untenable security situation on our northwestern flank. As it stands, the ROI displays sheer ambivalence towards its own security, and that of its partners. The inadequacy of the Irish Naval Service and Air Corps jeopardises the security of the Western Approaches to the British Isles, just when Russia has recalibrated its strategic doctrine and maritime capabilities to target our northern flank. Transatlantic undersea fibre-optic cables and European undersea energy infrastructure – so crucial to our collective prosperity and security – also traverse this maritime region, recreating its critical strategic importance of the 20th century. As long as the ROI cannot contribute to the defence of this zone, the UK must take this responsibility upon itself for its own security. This requires us to resurrect our naval and air forward presence in Northern Ireland.

Meanwhile, the ROI’s security porousness – and soft border separating it from British territories – opens the UK up to hostile subversion through the back-door. As long as the ROI has almost no cyber resilience nor robust counterintelligence apparatus to speak of, its systemic importance to the global economic order, and direct link to the UK, will remain an enormous liability. Institutional and societal penetration in the ROI by hostile states is also probable, given its weak security state and close transatlantic and European ties. Whilst the UK cannot solve these chronic internal issues on the ROI’s behalf, the seismic shock caused by shifting Northern Irish policy should impress upon Dublin that the UK will no longer tread with caution around issues affecting its national security. Afterwards, forceful British diplomatic efforts should prompt the ROI to begin contributing its fair share to the preservation of the order which benefits us all.

Chapter I presents the history of the strategic relationship of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, in order to reveal how external aggressors have always attempted to undermine the former through the latter. As Irish nationalism gathered momentum, eventually culminating in independence, Ireland’s global posture has consistently been informed by its desire to distance itself from the UK.

Chapter II analyses the contemporary strategic landscape facing the UK and the ROI. It is demonstrated that the ROI is an open target for attempts by Russia, China and Iran to subvert the transatlantic-European global system. The ROI’s vulnerabilities directly affect British security, as geographical proximity means that hostile intrusion into one’s sea and air space is a mutual danger. Equally, close bilateral economic and political ties ensure that cyber-attacks and espionage on one may compromise the security of the other.

Chapter III portrays the extent of the ROI’s historical and contemporary unreliability as a security partner. A selectively interpreted neutrality policy, woeful military and state security apparatus – the result of decades of under-investment – and the looming spectre of a Sinn Féin government next year all merge to constitute an entirely deficient partner in the face of modern threats.

Finally, Chapter IV proposes a roadmap for resurrecting the UK’s strategic presence in Northern Ireland. The Russian menace demands the restoration of a Northern Irish forward deployment platform near the Western Approaches and oceanic peripheries (west to the Greenland-Iceland-UK [GIUK] Gap, and north towards the High North). The UK’s diplomatic engagement with Ireland must resolutely maintain the position that such actions fall within the boundaries of the Downing Street Declaration, and are necessitated by the ROI’s inaction.

It is high time for the UK to acknowledge that the security arrangement on the island of Ireland runs counter to its interests. The Republic of Ireland is simply not a reliable partner in the current geopolitical environment, which places renewed importance on Northern Ireland’s role in British defence. By breaking the longstanding linkage between a British military presence in Northern Ireland, and fraught historical tensions, the UK would signal to the ROI that it will no longer shy away from the measures necessary to protect its national security. The longer term goal will be to create the environment for formulating a stronger, more equitable British-Irish security relationship, which is based on rational strategic interests, rather than deep-rooted political tensions.

In a clear example of Churchill’s dictum that, “at the summit, true strategy and politics are one”,4Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918, abridged and revised edition (New York: Free Press, 2005), 294. preserving the strategic unity of the Union is an inextricable component of British grand strategy. In doing so, the strategic indivisibility of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – which, despite subsequent interpretations, the Downing Street Declaration did enshrine – must be rediscovered.

Next chapterChapter I: The Historical Basis of a Troubled British-Irish Strategic Relationship

1.1: Introduction

History demonstrates the fundamental importance of a strategic presence on the island of Ireland to British – and Irish – security throughout any period of geopolitical disruption. In fact, the two islands’ security conditions have aligned so closely in the face of external threats that the strategic reality can be characterised as one of British-Irish interconnectedness, despite political friction and contemporary and historical ROI intransigence. As Irish nationalism emerged towards the end of the 18th century, calls for an independent political space, based on a distinct Irish character, began to strain this British-Irish strategic unity. In the end, political imperatives triumphed over strategic ones in 1938, when the UK forfeited its key naval bases on Ireland. This mistake – which could have cost the Allies victory in the Second World War – was only atoned for by the establishment of a strong naval and air presence in Northern Ireland.

Throughout the Cold War, the ROI’s continual desire to distinguish itself politically and strategically from the UK spilled over into its relationship with NATO, creating a gap in the Atlantic Alliance for Soviet exploitation. Again, the UK compensated for the Free Irish State’s strategic intransigence by building up its military presence in Northern Ireland. The underlying contradiction between strategy and politics reached its culmination point with the Troubles, however, which finally led the UK to withdraw its remaining active military presence on Ireland. As the modern geopolitical situation deteriorates, the untenable nature of the UK’s strategic position – lacking a forward presence in Northern Ireland to compensate for an uncooperative and poorly-equipped Ireland – has been laid bare.

1.2: The British-Irish Strategic Relationship – Historical Foundations

| The indivisible histories of the people of Great Britain and Ireland |

| The close cultural, political, economic and social ties between the people of Great Britain and Ireland have extremely deep roots. Indeed, the histories of the two islands are so intertwined as to be inseparable.

Whilst Ireland has been of crucial strategic importance to Britain since the 16th century,5Halford Mackinder, Britain and British Seas (London: Heinemann, 1902), 19-21. mercantile contact between the two islands long predates that. In early history, coastal settlements were by far the most viable locations for major human population centres, since maritime trade was of much greater efficiency than any land-based alternative.6Geoffrey R. Sloan, The Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations in the 20th Century (London: Leicester University Press, 1997), 67-74. This generated extensive cultural, economic, political, and strategic contact – both competitive and violent, and mutually beneficial – from the 11th century onwards. The Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland combined with longstanding economic contact between Great Britain and Ulster, Leinster, and Munster, to link British and Irish political fortunes closely.7FX Martin, “Chapter 3: Allies and an overlord, 1169–1172”. In Art Cosgrove (ed), A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534 (Oxford University Press). Close people-to-people relations ensured that the Irish featured in all of the major developmental phases of British modern history. Ireland contributed Jonathan Swift, Edmund Burke and George Berkeley to the English Enlightenment; Samuel Greg – pioneer of the factory system – to the Industrial Revolution; and over 100,000 Irish men and women served in the British Army during the Second World War.8Geoffrey Roberts, In service to their country: Moving tales of Irishmen who fought in WWII, Irish Examiner, 29 August 2015, https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/arid-20350818.html. The insoluble links between the two islands were always clearly understood. In the 1790s, Irish nationalism emerged with the founding of the Society of United Irishmen, which took inspiration from the tenets of the French Revolution. Irish nationalism was therefore preconditioned on the rise of other nationalist movements in the modern era, rather than any unified identity distinct from Great Britain in historical, cultural, economic or political terms. Instead, much like in Great Britain and feudal Europe, the origins of an Irish polity are found in the shifting alliances between local lords competing for territories and resources. Indeed, although there is no natural geographical demarcation line between different parts of Ireland, the island itself has always been fragmented along distinct cultural and social lines. Maritime contact between the Irish east coast and the British west coast both fostered close cultural and social ties between these opposing sides of the Irish Sea, and reinforced the cultural divisions between southwestern, eastern, and northeastern Ireland.9See M.W. Heslinga, The Irish Border as a Cultural Divide, (London: Van Gorcum, 1979). This complex history partly explains the difference in affinity felt by the Irish towards the Union, a contributing factor to the politically febrile period running from 1790 until the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. |

Throughout the course of modern history, external rivals sought to activate Ireland as a strategic pressure point against England. Ireland presented a potential launchpad for any invasion of Britain, considering the relative ease of access an invasion force has to the British west coast through the Irish Sea, despite its notoriously choppy waters.10Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 78-79. As international trade expanded and the power of the modern state developed, the role of Ireland in the British Isles’ defence system became readily apparent.

During the Wars of the Spanish and Austrian Succession, France sponsored anti-English political coalitions in Ireland, while the Jacobites attempted two more uprisings – in 1715 and 1745 – which received support from Irish Catholic aristocrats.11Ibid., 99-100. France again turned to Ireland as a lever against British power in 1796-1798 during the French Revolutionary Wars. The French Directory executed two invasion attempts, hoping to land a sizeable invasion force in Ireland that would at minimum tie down British resources and divert attention from the Continent, and at best enable an invasion of England.12Donald R. Come, “French Threat to British Shores, 1793-1798”, Military Affairs, 16:4 (Winter 1952), 174-188.

Although both French invasion attempts failed, the shifting European strategic situation necessitated a wholesale re-evaluation of British-Irish political relations. The 1800 Acts of Union, which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as a modern political entity, were meant to formalise Ireland’s political linkages to Great Britain, thereby solidifying the strategic unity of the British Isles against a persistent, expanding Continental threat.13Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 100-109. The result was a state, recognisable today, with a distinctly multinational character. Although the Acts of Union ameliorated potential political disruption, the strategic situation nevertheless necessitated a comprehensive defence network that included Ireland, which the UK built out over the next half-decade, until Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar broke French naval power and reduced the odds of an invasion.

Post-Napoleonic Britain, until the mid-19th century, was in an extraordinarily secure strategic position. The Congress of Vienna had created a reasonably stable balance of power between the major Continental actors, while also providing conservative forces in Europe an incentive to avoid war, and by extension war’s domestic stresses, in light of the growth of liberalism.14Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994) 78-102. The British strategic picture rested upon one core proposition: the identity of European littoral sea control and global sea control.15Aaron Friedberg, The Weary Titan: Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 138-140. There was no power beyond Europe, whether in Eurasia or the Americas, that could legitimately challenge British naval dominance. Moreover, the UK held a number of crucial naval installations in the Mediterranean that, when coupled with British bases in the Channel and on the Irish coast, ensured British control of the European littoral.

The Irish role in the balance of power established by the Concert of Europe is poorly appreciated historically. The Channel prevented the Russian Navy’s from breaking out into the open ocean from its Baltic base, thereby necessitating that Russia maintain cordial relations with the UK, or risk economic collapse and invasion – threat the UK nearly made good on during the Crimean War. However, France’s long Atlantic coastline provided ample trade nodes and naval basing for a French fleet beyond the English Channel. By operating naval forces from the Irish southern and western coasts, the Royal Navy could ensure its ability to blockade all French trade during wartime, thereby reducing the likelihood of Anglo-French enmity through a coherent strategic threat.16Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 114-119.

As French ambitions for European dominance re-emerged, France once again attempted to compromise the UK’s strategic position via Ireland. France sought to instigate a subversion campaign during periods of renewed tension with the UK in the late 1800s. Moreover, the rise of steam propulsion and concurrent advances in naval technology reinforced the need for access to Irish naval bases, since modern steam-powered warships, despite their speed advantage over tall ships, had to remain close to coaling stations during combat operations. The Irish coast provided an ideal set of bases for British naval operations in the north-eastern Atlantic, thereby defending British trade and serving homeland defence.17Ibid., 135-140.

Nevertheless, continued tension between the strategic British-Irish relationship and the political character of Ireland threatened to undermine the British Isles’ defence system – upon which Ireland’s external security rested as much as any other UK constituent nation. The strategic goal of Home Rule, from the viewpoint of homeland defence and geostrategy, was to placate growing Irish desires for a distinct political and cultural character, whilst maintaining the UK’s ability to include Ireland in its strategic posture. However, the long-term political effect of Home Rule was to fuel Irish nationalism. This continued tension would eventually push the strategic relationship between the UK and Ireland to breaking point, with deleterious consequences during the World Wars and Cold War.

1.3: The British-Irish Strategic Relationship – 20th Century Disruptions

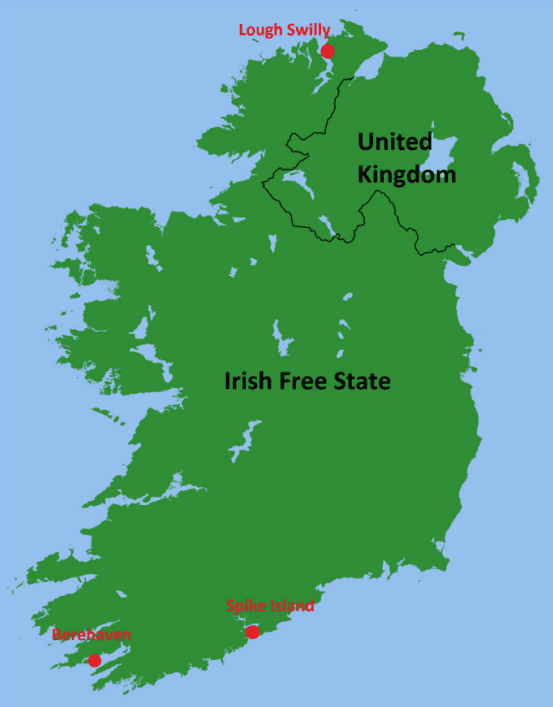

Prior to the First World War, Ireland was central to British defence planning. Ireland had its own Irish Command Scheme, which was plugged into the UK’s Home Defence strategic framework. The Irish component of British Home Defence was founded upon three ports – Spike Island and Berehaven in the south, and Lough Swilly in the north – which were integrated into a UK-wide coastal defence system.

The UK’s three Irish Treaty ports. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_Ports_%28Ireland%29

During the First World War, British strategy was centred upon the blockade of Germany, considering the Kaiserreich’s inability, in light of its geographical position, to access the open ocean and engage in international trade.18Robert Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (London: Vintage Books, 2007), 743, 768-788. Initial British policy rested upon the misguided view that Germany would unravel rapidly due to the commercial and financial disruption of the British blockade, leading to a rapid Allied victory.19See Nicholas Lambert, Planning Armageddon. This viewpoint was far from the mark, but the British blockade remained central to Allied strategy. The ability to defend and deploy from the three Irish ports was central to this strategy.

Although it took longer than anticipated, the British blockade became the most effective weapon against the Central Powers, because it could slowly but surely grind down German war-making capacity by starving it of resources.20Eric W Osborne, Britain’s Economic Blockade of Germany, 1914-1918 (London: Frank Cass, 2004), 153-170. Berlin never overcame this problem. It sought to break British naval power by drawing the Royal Navy into a naval battle on favourable conditions multiple times. But the only time the Grand Fleet and High Seas Fleet engaged in combat, at Jutland in 1916, the Germans took enormous damage – less than the British received, but far more in relative terms for a smaller Navy less capable of repairs.21Robert Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (London: Vintage, 2007), 658-670.

Germany’s ultimate response was the initiation of unrestricted submarine warfare, which ultimately birthed the Anglo-American Special Relationship. British-American cooperation was founded upon the issue of Irish defence, once the US had entered the war in 1917 following German commercial pressure. US destroyers based in Ireland helped police the Western Approaches, serving in a truly integrated command, which along with the convoy system helped master the U-Boat threat by 1918.22Ibid., 203, 232-234. Absent a unified British-Irish strategic space, the U-Boat campaign may well have succeeded in crippling the UK and forcing London out of the war, as it would have left it incapable of defending the Western Approaches. Clearly, the UK’s strategic position in Ireland was a crucial element of its broader defence system.

| The Western Approaches to the British Isles |

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Approaches The Western Approaches refer to the oceanic entry paths from the Eastern Atlantic into the British Isles. Their strategic importance is perennial: they are integral to Britain’s sea lines of communication, transatlantic maritime pathways, and northward deployment into the GIUK Gap and beyond. Today, major undersea cables run along the seabed, carrying digital data across the Atlantic. As an island nation, the sea has always mattered to Britain. Indeed, naval historian and doyen of maritime strategy, Halford Mackinder, understood better than anyone the function that sea power plays in British grand strategy, and consequently, its sustained prosperity.23H. J. Mackinder, Britain and the British States, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902), 12. Through the lens of his geopolitical analysis, the Western Approaches are one of three vital maritime components of the British Isles. The ability to control these regions, he argued, determined the strength of Britain’s strategic position.24Ibid., 11. Indeed, throughout history, the Western Approaches have always been essential to Britain’s ability to assert sea control and sea denial around its shores, and further west into the Atlantic. Viewed in this framework, Ireland’s oceanic exposure – as the first land mass reached from the Atlantic – and proximity to Great Britain, accounts for its strategic inseparability from the whole British Isles. It is via the Irish Sea that the Great British midriff plugs into the Atlantic, north-westerly via the North Channel, and south-westerly via St George’s Channel. As this chapter shows, whenever threatened externally, Britain’s security – and indeed that of Ireland –has always rested on its ability to control and deploy in the waters around Ireland. Thus, in the words of the Royal Navy’s Director of Naval Intelligence in 1932, “Ireland is a vital part of our home defences”.25Memorandum by Director of Naval Intelligence on the Irish Dispute, 6 October 1932, ADM 178/161. With no naval base in Northern Ireland, and a ROI with no serious navy to speak of, the UK’s homeland defence is severely weakened around the Western Approaches today. |

Unsurprisingly, like all of the UK’s Continental adversaries, Germany sought to reactivate the Irish problem for the UK. German intelligence had extensive contacts with the Irish Republican movement, and was a supporter of the Easter Rising.26Geoffrey Sloan, “The British State and the Irish Rebellion of 1916: An Intelligence Failure or a Failure of Response?” Journal of Strategic Security, 6:3 (Fall 2013), 328-357. Although the Rising failed to eject British forces from Ireland or tie down significant numbers of British troops, it nevertheless demonstrated the chronic vulnerability the Irish political situation posed to UK strategy and the defence of the British Isles.

The Interwar Period was defined by an unravelling of British strategy towards Ireland, with dangerous consequences once the Nazi threat matured. After 1919, British defence planning rested upon the Ten-Year Rule, the assumption that no major threat would emerge and cause a great power struggle for the next decade. Nevertheless, the British-Irish War of 1919-1921, combined with the memory of German disruption in Ireland and the U-Boat threat, impressed upon British strategists the need to maintain some strategic coherence in the British homeland defence system, even absent British-Irish political unit.27Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 177-178. Like Irish Home Rule, the Irish Free State was constructed as a compromise measure, acquiescing to Irish nationalistic calls for an independent political identity, while preserving a military presence on the island, which was critical to the security of the UK.28Ibid., 179. Northern Ireland therefore remained an indivisible part of the Union for cultural and economic reasons, but also for strategic motivations, since it provided the UK direct access to some basing in Ireland, despite revised political arrangements. Indeed, it is here that Northern Ireland’s unique strategic importance emerges: absent guaranteed access to all of Ireland, the UK required some unrestricted access to meet basic strategic needs for homeland defence.

The most critical element of the independence negotiations was the Treaty Ports system, under which the UK retained control over its three Irish deep-water ports: Berehaven, Spike Island and Lough Swilly. British negotiators insisted upon the Treaty Ports for strategic reasons throughout the negotiations, despite periods of Irish intransigence.29Ibid., 183-185. The Treaty Ports were as relevant to the Irish Free State as to the UK; absent integration into the British defence system, the newly-independent Irish Free State would be unable to defend itself against any predatory European power.

However, British strategic myopia and continual political tensions with the Irish Free State eventually led to the unravelling of this arrangement by 1938. After the First World War, British defence planning fragmented, as each military service pursued an independent strategic policy. The result of this inter-service competition for funding was ultimately a diminished naval presence on Ireland.30See John Robert Ferris, Men Money and Diplomacy.

Moreover, in the early-1930s, Irish politics took a distinctly Anglophobic turn with the accession of Eamon de Valera to the Irish premiership. De Valera rapidly revised the British-Irish relationship, abrogating or violating multiple clauses in the 1921 British-Irish Treaty. He then initiated an enormously self-damaging trade war against the UK, hoping to industrialise Ireland.31Kevin O’Rourke, “Burn everything British but their coal: the British-Irish economic war of the 1930s.” Journal of Economic History, 51:2 (1991), 357–366. However, during negotiations to end the trade war in 1938, diplomatic pressure led the UK to consent to surrendering the Treaty Ports in order to settle the economic dispute. Given the lopsided damage Ireland incurred through the trade war, sacrificing the ports amounted to an enormous strategic miscalculation by the British. For the first time in modern history, the UK had abdicated its ability to maintain security in the Western Approaches.

The implications of this decision became clear only two years later, when the UK found itself alone against a Europe under near-total German domination. With the Fall of France, German U-Boats gained direct access to the Atlantic, and thereby could pressure the Western Approaches, jeopardising British supplies. During the First Happy Time, in the second half of 1940, German U-Boats sank nearly 1.5 million tons of supplies carried by 282 merchant ships.32See “WWII Ship Losses By Month”, accessed via: https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/losses_year.html; See also Marc Milner, “The Battle That Had to Be Won”, Naval History Magazine, 22:3 (June 2008), accessed via: https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2008/june/battle-had-be-won. Combined with the German air assault on the UK, and obvious preparations for cross-channel invasion, the British strategic situation seemed increasingly dire.

Had the UK retained access to the Treaty Ports, it could have deployed Royal Navy destroyers to Ireland. These would have been able to screen convoys in the Western Approaches, particularly if the UK had also built out airfields in each Treaty Port. In the event, the UK struggled to implement a coherent system of trade protection, even with the reinstitution of convoys. London repeatedly petitioned Dublin to abandon neutrality and, at the least, accept British redeployment to the Treaty Ports. De Valera refused, privately stating that he was convinced of German ascendance.33Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 205. In the event, the UK had to expend enormous resources building out air and naval bases in Northern Ireland, while rerouting convoys away from the Western Approaches farther north. Had the UK not preserved Northern Ireland’s place in the Union, there would have been no practicable mechanism for the protection of the Western Approaches.

As with the First World War, American assistance in fortifying naval bases on Ireland came to the UK’s rescue. In a move which would prove decisive in the Battle of the Atlantic, the US clandestinely deployed several hundred “advisors” to HMS Ferret, the British shore establishment at its new naval base at Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The UK ultimately survived the U-Boat threat with an empowered Coastal Command, and enormous expenditure into developing maritime patrol and convoy escorting capabilities at and around Londonderry, enabling its forces eventually to cover the “Mid-Atlantic Gap”.34John Hedley-Whyte and Debra R. Milamed, Battle of the Atlantic: Military and Medical Role of Northern Ireland (After Pearl Harbour), Ulster Medical Journal, 2015, 84)3), 183-186. It was only due to American resources and British-American ingenuity that American supplies, and later, American ground forces, reached the UK for the Liberation of France. Indeed, the Anglo-American Special Relationship was again founded upon cooperation in Northern Ireland, necessitated by Dublin’s political hostility to London.

Throughout the war, German intelligence assessments indicate that Berlin was well aware of the stresses Irish neutrality caused to the Allies. Even once the U-Boat threat was mastered, the Irish coastal “dead zone”, as German analysts termed it, restricted Allied strategic options.35Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 227. Allied intelligence officers, meanwhile, were extraordinarily nervous that well-established German intelligence activity in Ireland would tip off the Wehrmacht as to Operation OVERLORD’s objective of landing at the Normandy beaches. Indeed, this was far from paranoia, for the Irish handed critical intelligence to Germany before the Allied assault on Arnhem, allowing the Germans to pre-empt, and ultimately withstand, the attack.36J.P. Duggan, Neutral Ireland and the Third Reich, (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1989), 237.

The above demonstrates just how critical sustaining a military presence on Ireland, and particularly in Northern Ireland, is for the UK’s security in the face of external threats. Major-power conflict is always a close-run thing. Had the UK not been quite as adaptable, and had the US not been capable of applying its full industrial capabilities against the German threat, the vulnerability of the Western Approaches may well have knocked the UK out of the war. Military presence near the Western Approaches was therefore the understated lynchpin of Allied strategy in the Second World War – just as in the First – without which Germany might well have won.

1.4: The Strategic Problem from the Cold War Until Today

The British-Irish strategic relationship, which after 1937 became the UK-ROI strategic relationship, evolved following the end of the Second World War, but its baseline characteristics, and the strategic difficulties which defined it, remained largely identical. This further attenuated the strategic element of Unionism, despite its burial in the historical record.

Throughout the Cold War, the ROI occupied a curious position. The UK and US both immediately invited the ROI to join NATO upon its founding in 1949. This was spurred as the Western Approaches question remained extremely live in the aftermath of the Second World War for two reasons. Firstly, any NATO defence strategy would involve an enormous amount of follow-on forces transiting to Europe to counter a Soviet offensive, passing through the Western Approaches for a combat power build in the UK and, if possible, France. Secondly, the proliferation of strategic bombers and nuclear weapons raised the risk of a Soviet attack following that same route.

However, due to its policy of neutrality – codified in the 1937 Constitution –37See Chapter III for more discussion of Irish neutrality. the ROI neither joined NATO nor permitted a major NATO presence, despite its ideal positioning as the backstop to a broader European defence system. Throughout the Cold War, Ireland consented to NATO accession only if Northern Ireland joined the Republic.38For example, in a Dáil session on 23 February 1949, Minister for External Affairs Seán MacBride explicitly links Ireland’s refusal to join NATO to the presence of British forces in Northern Ireland “against the will of the overwhelming majority of the Irish people”. Seán MacBride, Dáil session, 23 February 1949, quoted in Dennis Driscoll, Is Ireland Really ‘Neutral’?, Irish Studies in International Affairs, 1982, 1(3), 55. The issue was, Ireland would provide no prior guarantees of either NATO membership or NATO access before this point. Hence the UK, and by extension the US, had no incentive to encourage serious talks on Irish unification, and thereby surrender NATO’s last remaining potential basing locations in Ireland, at the cost of breaking the Union. Moreover, even if the ROI joined NATO, there was almost no likelihood that it would abide by its 2% of GDP defence spending threshold, which would therefore necessitate even more Allied assets to secure its air and maritime space.

From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, the UK therefore met its strategic requirements in Ireland by maintain its air and naval bases, and developing an early warning build-up in Northern Ireland. Londonderry remained the primary naval and air deployment base for Allied defence in the Greenland-Iceland-UK Gap (GIUK Gap). RAF Bishopscourt, established in 1943, became the base for the transatlantic military radar system, critical to UK and allied nuclear early warning on its northwestern flank. The British government therefore attempted to maintain its military presence in Northern Ireland – so critical to transatlantic air and maritime defence – in a manner which did not exacerbate political tensions with the ROI.

However, with the emergence of Irish paramilitary violence against British police and military personnel in Northern Ireland, this compromise strategic relationship became untenable. With the start of the Troubles in 1969, the political relationship between the ROI and the UK deteriorated rapidly. In response, the British Armed Forces launched Operation Banner in Northern Ireland. Operating from 1969 until 2007, with over 300,000 soldiers seeing service, Operation Banner holds the record for the UK’s longest continuous deployment.39Andrew Sanders, Times of Trouble: Britain’s War in Northern Ireland, (Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 109.

Thus, just as the UK entered a prolonged period of economic malaise, and was reducing its defence commitments around the world, the Army became embroiled in counterinsurgency in Northern Ireland. As Operation Banner was getting underway, the UK finally drew down all deployments East of Suez, fully handing over Middle Eastern strategic responsibilities to the US in 1971.40See W. Taylor Fain. American Ascendance and British Retreat in the Persian Gulf Region, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). It also greatly curtailed its military presence in the Mediterranean, restricting itself to a ground-centric mission in central Europe.

Driven by these economic factors, and the mounting pressure against its military presence in Northern Ireland, the UK began to close bases deemed unessential to maintaining stability. It was thus mostly naval and air bases which were shut down: Londonderry in 1970, RAF Ballykelly in 1971, and Bishopscourt by 1992. With the closure of these facilities, this was the first time since the 17th century that the UK was left without a military presence on its Irish maritime flank. As the Troubles escalated, Northern Ireland became a mission exclusively for the Army, while an understanding of Ireland’s role in British and Allied strategic defence receded from view.41Sloan, Geopolitics of British-Irish Relations, 259-260. Thus, even though it was the Army’s presence which would be treated officially in the Good Friday Agreement, the RAF and Royal Navy’s presence in Northern Ireland – which long predated the Troubles – was a secondary casualty.42UK Government, The Belfast Agreement: An Agreement Reached at the Multi-Party Talks on Northern Ireland, 21.

The official reasons given for this naval and air draw-down appear intentionally muddied. The UK and NATO justified the closure of Bishopscourt on the grounds that new, longer-range radar technology removed the need for a station in Northern Ireland.43Royal Air Force News Release, 15.90, 25 July 1990. However, other diplomatic and military officials at the time explained the closures as an olive branch to Sinn Féin in order to quell unrest. An unnamed official from the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs argued that the closure of Bishopscourt “was important to reassure Sinn Féin who had always assumed that this was the reason why Britain was still in Ireland”,44An interview with an unnamed official of the Department of Foreign Affairs, quoted in Sloan, The Geopolitics of Anglo-Irish Relations, 266. demonstrating again Sinn Fein’s fundamental misunderstanding of British strategic interests. Meanwhile, the last captain of Sea Eagle at Londonderry, Admiral Sir Antony Morton, stated that the start of the Troubles “created a pressure that made it impossible to sustain an international allied training centre… in Londonderry”.45Interview with Admiral Sir Antony Morton, 30 August 1995, in Sloan, The Geopolitics of Anglo-Irish Relations, 259.

The Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, and subsequent period of the Cold War Peace Dividend, concealed the strategic implications of the UK’s military draw-down in Northern Ireland. As a result, the strategic imperative to British and transatlantic security of maintaining an Irish presence played second fiddle to desires to end the violence in Northern Ireland. Central to the ultimate resolution of the Troubles through the Good Friday Agreement, the Downing Street Declaration of 1993 stated that the UK has “no selfish strategic” interest in Irish affairs.46Ibid. As has been demonstrated, construing this as a rejection of any British interests in Northern Ireland pays no regard to the vital role played by Irish military bases throughout British modern history – nor to the indivisible unity of the Union.

The upshot of the troubled strategic relationship between the UK and ROI is that any security alignment has been disavowed. Neither has the means to satisfactorily police the Western Approaches and Eastern Atlantic – the UK due to its lack of military presence, the ROI due to the chronic deficiencies of its Defence Forces, and political comfort with depending on the security umbrella provided by others. With the return of Russia as a direct threat to European and transatlantic security, there is a real prospect that the dormant risks, engendered by the strategic myopia exhibited by the UK from the 1970s onwards, will finally emerge to endanger our national security.

Next chapterIreland Chapter II: The Current Threat Landscape

2.1: Introduction

As shown, the ability to deploy and surveil the Western Approaches and Eastern Atlantic has been fundamental to the UK’s enduring security. Although the period of relative geopolitical peace between 1991 and 2021 obfuscated the implications of surrendering the Northern Irish bases, a resurgent Russian threat to Europe and the transatlantic alliance leaves the UK exposed to the fruits of its strategic negligence. In an era when technological advance provides hostile actors sophisticated means of waging unconventional warfare, the threat landscape has deteriorated significantly since the Cold War. Russia now possesses the means and intent to launch physical and cyber-attacks on the critical undersea infrastructure which connects our digital and energy systems to our surrounding partners. This places renewed importance on the UK’s ability to police its territorial waters, and to work with its allies towards wider defence around the North and Baltic Sea, the GIUK Gap and, increasingly, the High North.

Meanwhile, alongside Russia, China and Iran are also engaging in cyber and espionage tactics with the strategic objective of disrupting the informational, digital and financial systems upon which Europe and the transatlantic alliance rely. Whilst all countries struggle to build the necessary resilience into their cyberspace and intelligence networks, the ROI’s chronic deficiencies in these domains (Chapter III) single it out as the weak link in transatlantic-European systems.

In light of these multi-fronted assaults on Western security and prosperity, the UK must rediscover the fundamental role that Northern Ireland plays in its grand strategy. This chapter presents the threat landscape facing the UK, assesses the strategic ambitions and operational methodology of the three authoritarian aggressors, and exposes the extent to which the ROI’s chronic blindness towards its own security, and continuous hostility towards its only rational security allies, endangers that of its partners.

2.2: The British Isles within Eurasian Competition

The outbreak of the Ukraine War, and rising systemic hostilities with China, illustrate that the enduring security of the incumbent global system, so amenable to interests of the UK and the ROI, is being threatened across multiple theatres. Competition with Russia in the Euro-Atlantic, and China in the Indo-Pacific, are not isolated challenges, but are heavily interlinked in an ongoing battle across Eurasia to preserve the US-led world order against revisionist authoritarian states.47Sir John Jenkins et al., The Iran Question and British Strategy, Policy Exchange, 17 July 2023, https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/the-iran-question-and-british-strategy/. This geopolitical landscape is characterised by a complex array of threats: from the conventional warfare seen in Ukraine; to physical, yet below threshold, damage to critical infrastructure; to subversive tactics, such as cyber-attacks and the cognitive warfare of disinformation campaigns. Whilst the specific nature of these threats differs across the two Eurasian theatres, they are nonetheless linked by their broad tactical and operational similarities, the defensive responses they demand, and the mutual strategic ambition to challenge the US-led order.

The critical importance of approaching British national security through this broad geographical lens was successfully identified by the UK government’s Integrated Review Refresh in 2023. Whilst correctly asserting the Euro-Atlantic as the priority region for protecting our security and prosperity, the Refresh confirmed the concomitant exigencies of engaging – and, where necessary, competing – with China in the Indo-Pacific.48The Integrated Review Refresh, HMG, March 2023, 3; 19; 20-24. In doing so, the government correctly diagnosed the Eurasian threat environment, in which attention and resources must be prioritised – but nonetheless, shared – to uphold the US-led world order on two fronts.

From the perspective of strategic prioritisation, a British grand strategy has therefore been formulated on the basis of an eastwards shift, whereby we engage closely with Continental European allies and partners in the face of the Russian threat, whilst tilting overall strategic gravity to the Indo-Pacific to support the US in its contestation with China. This rationale has informed the UK’s latest flurry of diplomatic and military initiatives, from last year’s UK-France Summit, to the bilateral strategic partnership with Norway, to the Hiroshima Accord signed with Japan, and the AUKUS pact with Australia and the US. The ambition is to construct a constellation of alliances and partnerships in the face of Russian and Chinese threats, in which national resources are allocated so as to combine with those of our allies, to achieve our strategic objectives across Eurasia.

This is the landscape in which both the UK and the ROI are positioned. Acting as the geographical and strategic ‘gateway to Europe’,49Robert McCabe and Brendan Flynn, Under the radar: Ireland, maritime security capacity, and the governance of subsea infrastructure, European Security, 26 August 2023, 3. the UK and Ireland constitute the main highway for transatlantic goods, ships and digital communications. As demonstrated in the previous chapter, the decisive importance of maintaining free maritime and air access around British-Irish coastlines and oceanic approaches has been exhibited throughout history. Although the region did not exhibit its strategically vital nature overtly during Europe’s period of relative peace between the end of the Cold War and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this does not mean that it dissipated. In fact, peacetime developments have brought further strategic importance to waters surrounding the UK and the ROI, through the exponential build-up of critical maritime infrastructure, which carries energy and digital data across the Atlantic and Europe.

Following the end of the Cold War, Western European states sought to maintain Continental security by establishing a mutually beneficial, integrated economic system, insured by the NATO security umbrella. From 1993, the newly-formed EU welcomed post-Soviet central and eastern European states rapidly, forming a formidable economic bloc. The EU swiftly became the most interconnected economic unit on the globe, as intra-regional trade has consistently accounted for two-thirds of the bloc’s total trade.50Shannon K. O’Neil, The Globalisation Myth: Why Regions Matter, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022, 41. Whilst the EU promoted political union and some measures to achieve collective defence and foreign policy, its fundamental principle remained that encouraging buy-in to mutual economic security would sustain the continent’s stability.51EU Commission, An EU approach to enhance economic security, 20 June 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_3358. This was similarly reflected in its post-Cold War approach to the Russian Federation, which established strong energy ties with the former adversary to create symbiotic interest in peaceful relations. A two-tiered, interconnected, transatlantic-European security system therefore characterised the period 1991-2021, whereby the continent’s stability was to be guaranteed by its economic integration, with the NATO security framework acting as insurance of the last accord.

With interconnection comes interdependence, as each state has come to rely on the critical infrastructure which undergirds their social, economic, political and military systems. Returning to the global threat landscape, targeting these infrastructural sites presents a strategically invaluable opportunity to cause system-wide disruption, whose consequences will reverberate across borders. This systemic potential is obviously attractive to the ambitions of our adversaries: whether China – which seeks wholesale revision of the US-led world order, Russia – which wishes to subvert the incumbent European framework, and displace the US as the primordial power within it – or the Islamic Republic of Iran – whose survival strategy entails imposing destabilising costs on western nations to weaken their resolve in sustaining economic and diplomatic pressure on the regime.52Sir John Jenkins et al., The Iran Question and British Strategy.

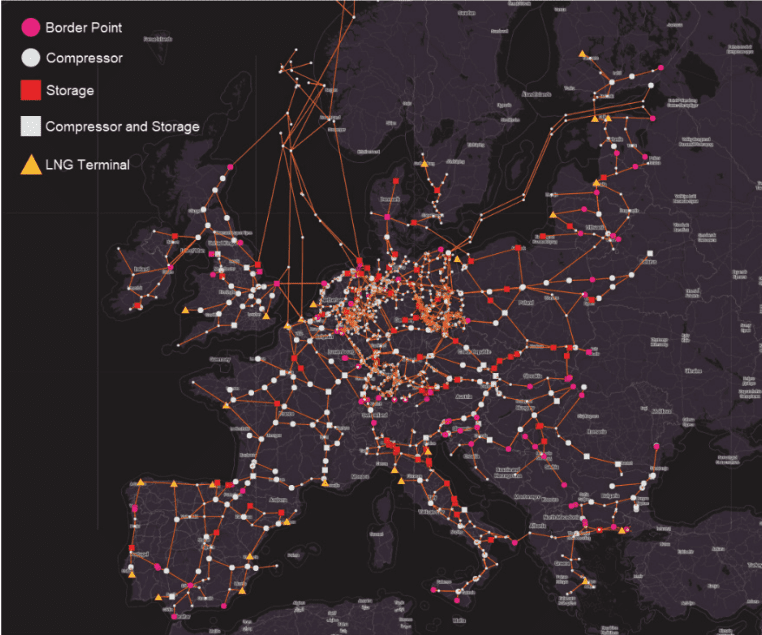

Thus, whether it is an undersea fibre-optic cable connecting the US and the UK, or a gas pipeline running from Norway to Germany, each component of these intercontinental systems represents a target through which to damage all constituents. The overarching security landscape, and all national security within it, has thus transitioned away from the protection of critical national infrastructure to that of critical infrastructure of international relevance. The UK and ROI’s position at the epicentre of transatlantic movement and communications makes them both vital to the overall stability of the entire system.

The two states of the British Isles therefore comprise primary targets for adversaries seeking to undermine the transatlantic-European alliance by compromising its vital energy and communication systems. As island nations, the UK and ROI both rely upon undersea pipelines for their energy supplies. Furthermore, both are net energy importers. The UK imports 50% of its gas, with 77% crossing the North Sea from Norway.53ONS, Trends in UK imports and exports of fuels, 29 June 2022, https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/articles/trendsinukimportsandexportsoffuels/2022-06-29. Ireland is even more dependent on the international energy market, importing 100% of its oil and 71% of gas.54International Trade Administration, Ireland Energy Security Supply, 27 September 2022, https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/ireland-energy-security-supply. The closely aligned strategic interest that the UK and ROI have in the security of these channels is underscored by the fact that 75% of the ROI’s gas currently flows from the UK via two pipelines.55McCabe and Flynn, 4. This figure was as high as 95% before 2016, in which year the ROI’s Corrib gas field began to supply the nation.56Ireland 2050, Where does our gas supply come from?, https://irelandenergy2050.ie/questions/where-does-our-gas-supply-come-from/. The Corrib field is relatively small, and is set to go out of operation in 2030, at which point the ROI will become entirely dependent on the UK again, barring further developments.57Privacy Shield Framework, Ireland – Energy – Oil & Gas, https://www.privacyshield.gov/ps/article?id=Ireland-Energy-Oil-Gas#:~:text=Ireland%20currently%20has%20two%20main,due%20to%20cease%20by%202021). Thus, for the foreseeable future, UK-ROI energy security is dependent on the security of undersea maritime infrastructure crossing the North Sea.

EU natural gas pipeline network, 2022. Source: https://memgraph.com/blog/gas-pipelines-in-europe

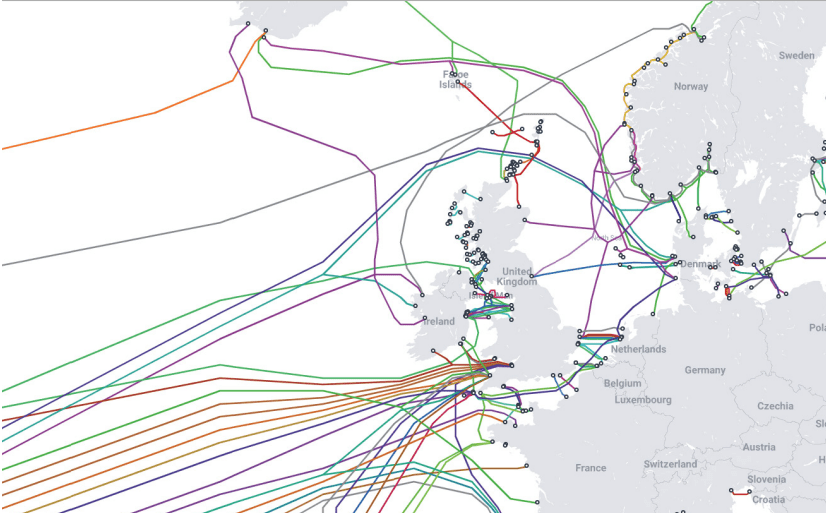

Even more important to wider transatlantic-Europe security is the UK-ROI function as a major node of the northern hemisphere’s undersea fibre-optic cable network. Three-quarters of all northern hemisphere undersea cables run through the ROI’s territorial waters alone.58Ibid.

Source: https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

This undersea network constitutes the digital connective tissue upon which the social, economic, political, and military systems of the transatlantic community depend. Its fundamental importance to the security of all states, therefore, cannot be overstated and, as a result, nor can that of the UK-ROI node within the wider system. This affords adversaries the opportunity to infiltrate, or outright damage, the digital channels which service the entirety of the transatlantic-European economic and security systems. Furthermore, the porous international legal framework governing undersea activities, provided by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), places responsibility firmly on countries themselves to deter hostile acts. However, policing and protecting these cables rigorously requires highly sophisticated technological and operational capabilities. This renders cables exceedingly vulnerable both above and below the conflict threshold.

Crucially to the Eurasian competition landscape, whilst geography dictates that Russia alone can access this infrastructure in the Euro-Atlantic for physical explorative and exploitative purposes, cyber sabotage can originate from anywhere. It is therefore a genuine and plausible target in the entirety of the Eurasian battleground, whether by state actors (China and Iran), or non-state groups.

2.3: The UK’s Exposure on its Northwestern Flank

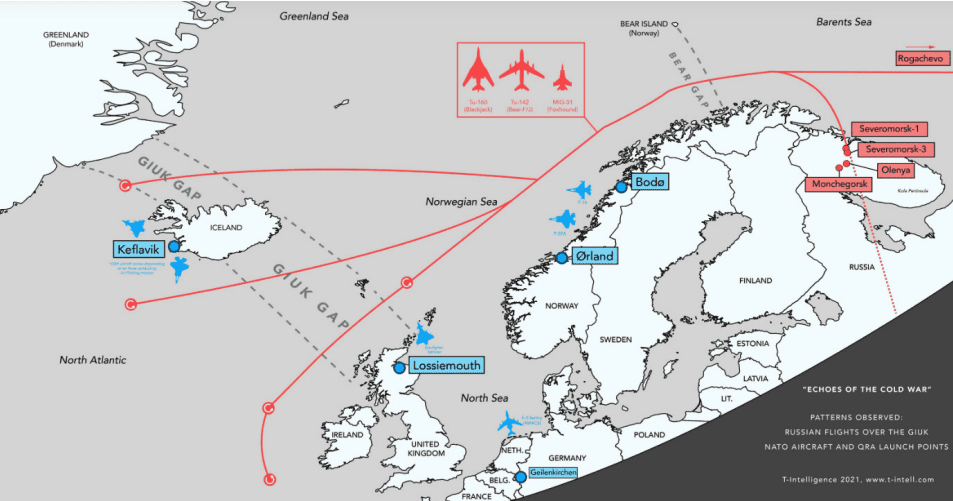

Chapter I provided the historical context for the UK’s current lack of military presence in Northern Ireland. This limits its deployment capacity through the Western Approaches towards the GIUK Gap and North Atlantic. As Russia has returned as a threat to European and transatlantic security, and climate change promises to increase accessibility to and from the High North, the full strategic implications of the Royal Navy and RAF draw-down from the 1970s is becoming clear.

Source: https://t-intell.com/2021/03/30/echoes-of-the-cold-war-why-bears-like-the-g-i-u-k-gap/

The UK’s nearest deployment platforms to the North Atlantic and High North are currently HM Naval Base Clyde, and RAF Lossiemouth.59UK House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee, Defence in Scotland: the North Atlantic and the High North, 10 July 2023, 26-27, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/40994/documents/199642/default/. With four Typhoon Squadrons, nine P-8A maritime patrol aircraft, and the new fleet of E-7 Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning aircraft all hosted at Lossiemouth, the UK’s northern Quick Reaction Alert is well established.60Ibid., 27. This enables the UK to patrol the area up to the High North, which it does alongside regional allies in order to deter Russian airborne aggression.61UK MoD, The UK’s Defence Contribution in the High North, UK Gov, 29 March 2022, 13, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6241cd63d3bf7f32b2e52515/The_UK_s_Defence_Contribution_in_the_High_North.pdf. Meanwhile, the UK Air Surveillance and Control System is fully integrated into NATO’s Control and Reporting Centres. Through the node of RAF Boulmer in North Yorkshire, this gives the UK high level radar coverage spanning from the Western Atlantic to 3,000 miles across Eastern Europe.62Armed Forces, UK Air Surveillance and Control System (ASACS), http://www.armedforces.co.uk/raf/listings/l0016.html.

Whilst the gap created by the RAF draw-down in Northern Ireland has therefore been mostly mitigated, British naval capacities on the left of the Western Approaches remain limited. Maritime patrol of these waters, and by extension the Eastern Atlantic, depend on rapid naval deployment to interdict hostile intrusion. As shown, major transatlantic undersea cables pass through this region en route to the UK and the European Continent. The Derry naval base was perfectly located for maritime policing deployment, which has become a renewed imperative due to the array of threats Russia poses in the maritime domain.

In 2022, Russia shifted the Arctic to its top priority region with its new Maritime Doctrine.63Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation, 31 July 2022, (http://pravo.gov.ru/), translated by Anna Davis and Ryan Vest, US Russia Maritime Studies Institute, 24-25. As the Baltic and Atlantic place in second and third, this shows the threat trajectory which the UK faces to the north and west. Whilst the next section details the specific Russian activities in this domain, the general implications for our northwestern defence system were articulated by the International Relations and Defence Committee’s recent report on British strategy in the Arctic.64House of Lords International Relations and Defence Committee, Our friends in the North: UK strategy towards the Arctic, 29 November 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/42335/documents/210453/default/. As the UK and its allies respond to Russia’s strategic shift, the strain on attention and resources is set to intensify. Minister of State for the Armed Forces James Heappey acknowledged that existing maritime patrol capabilities in the region may no longer suffice, as our current fleet of P-8 aircraft was structured to meet Russia’s aims before its strategic recalibration.65James Heappey MP, oral evidence given to the House of Lords International Relations and Defence Committee, 5 June 2023 (Session 2022-23), 37, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/42335/documents/210453/default/. Also last year, the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee released a report titled Defence in Scotland, which expressed the repeated concerns of experts that bases in Scotland are likely to be over-stretched by growing capability demands.66House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee, Defence in Scotland: the North Atlantic and the High North, 21 July 2023, 32-33.

This trend is only set to increase, as Russia’s freedom to manoeuvre from the north towards Atlantic and GIUK Gap will improve as warming temperatures continue to melt the Arctic ice. The report notes that the central Arctic Ocean will be mostly free of ice in the summer by 2040-2045,67Ibid., 4. a development which is already turning the previously uncontested region into a new frontier of geopolitical competition. Thus, this combination of political and environmental forces is set to – indeed, already has – alter the baseline defensive needs of the UK on its northern and western flanks. With an uncooperative and unequipped Ireland (Chapter III), there is a renewed compulsion for the UK to refocus on Northern Ireland as a central element of its homeland and regional defence system.

Within this strategic context, the following sections outline the specific nature of the threats posed to British-Irish security – and as a corollary, to European and transatlantic – primarily from Russia, but also China and Iran.

2.4: The Russian Threat

The grand strategy informing Russia’s global activities under President Vladimir Putin is its desire to re-wire the post-Cold War European security system, in order to displace the US as the region’s great power. This ambition has ideological and political-economic rationales.

The former stems from Putin’s guiding faith that his nation’s geopolitical, economic, and cultural DNA grants it unalterable, enduring great power status, a belief he has articulated many times over the decades.68Vladimir Putin speech, Russia at the turn of the millennium, 30 December 1999, https://pages.uoregon.edu/kimball/Putin.htm. Ever since the initiation of Peter the Great’s nation-building quest 300 years ago, and Catherine the Great’s great southwards expansion, the centre of gravity of Russia’s great power credentials has always been Europe. It is in this continental theatre that Russia has lost and regained its relative power repeatedly in the intervening years, until – in the eyes of its current President – the West brought about its last national humiliation in 1991. He is now hellbent on restoring Russia’s former status, which guides his competition and contestation with the West across the globe. The kernel of this revisionist doctrine is, of course, Europe, attested to by Russia’s persistent, and ultimately futile, efforts to sever the Baltic states from the transatlantic alliance, and its invasion of Ukraine.

To serve this overall ambition, Putin has structured the post-1991 political-economy of the Russian Federation, to enable his authoritarian control over national resources to channel them in their entirety towards his geopolitical aims. Having assumed power in 2000, the President dismembered the Russian oligarchy, stripped them of their assets, and awarded them to a parallel new elite.69The phenomenon was noticeable by the late 2000s. See Daniel Treisman, “Putin’s Silovarchs”, Orbis, 51:1 (Winter 2007), 141-153. This has engendered centralised control over all production and resources, but also an absence of free market dynamics which is anathema to the economic model established by the EU. Whilst acquiescing to the energy ties established by Russian gas exports to Europe, the Russian Federation’s wider economy remains insulated from the global economic system, maintaining Putin’s capacity to channel national resources towards great power competition.70See Sam Greene and Graeme Robertson, Putin vs the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia (London: Yale University Press, 2019). The implementation of western sanctions against Russia following the 2014 invasion of Crimea, and ongoing Ukraine War, further calcified the political-economic divergence between Russia and the West, a situation determined by the President’s revisionist ambitions.

As this grand strategy has intentionally – and resultantly, through reactive measures – created deepening systemic bifurcation between Russia and the West, this in turn gives Moscow tactical options within the subthreshold context, aimed at degrading the transatlantic-European economic and security networks. Before assessing these, it is crucial to emphasise the ROI’s particular susceptibility to these threats as a vulnerable entry point to these systems. Firstly, its geographical isolation from Europe, and vast oceanic exposure to the north and west, gives ready access and manoeuvrability to adversaries approaching by sea and land. Secondly, the ROI’s paradoxical position as a non-NATO member, yet one which is structurally integral to transatlantic sea and air movement and digital communications, affords Russia the opportunity to target these systems within the ROI’s territory, safe from triggering NATO’s collective security mechanism. This particular strategic vulnerability has been heightened by Finland and Sweden’s (imminent) accession. This has turned the ROI into the northwestern outlier in NATO’s European territories, increasing the probability of the Kremlin targeting it as a means of destabilising the alliance through the back-door.71McCade and Flynn, 17.

The Russian threat to the ROI falls into two categories: conventional conflict and unconventional pressure. Whilst the former is at least hypothetically possible, due to Russia’s possession of aircraft and naval forces capable of reaching Irish territory, it is parenthetical in the isolated context of the ROI; Russian territorial expansionism is part of a much broader set of issues that the NATO bloc as a whole must confront. In any case, Russia’s military is locked into the brutal Ukraine War, and so there is no conceivable strategic objective for invading Ireland at present, which would justify the necessary transportation of naval equipment, forces and materiel to the Federation’s Northern Fleet bases, from which to embark upon the long-winded route through the High North and Eastern Atlantic. Therefore, the Commission on the Irish Defence Forces (see Chapter III) assessment for the year 2030 and beyond – that the risk of conventional military attack is low – is correct.72The Commission, 5.

Instead, Russia poses a range of unconventional threats which would involve infiltration, and physical and cyber-attacks, on the ROI’s critical infrastructure, national IT systems, institutions, and intelligence-based national security agencies. All of these, considering the UK’s geography, are equally relevant to British interests. Hostile activity may all occur – and per the below, evidence suggests that the ROI has already experienced them – below the conflict threshold, owing to difficulties in attributing blame, and porous legal governance of these domains. Through utilising such tactical variety, Moscow seeks to spread the attention and resources of security apparatus thin, so as to impose greater costs and increase the chance of success in any one area. It bears repeating that such measures would endanger both national security, and that of the European and transatlantic systems in which Ireland resides.

2.4.1: Critical maritime infrastructure

The most acute vulnerability the ROI has in the Russian context is to the critical maritime infrastructure located in its territorial waters. There are two factors behind the primordial status of this threat: the ROI’s sheer vulnerability, and Moscow’s significant capabilities and intent in this domain.

Firstly, as mentioned, three-quarters of northern hemisphere undersea cables travel through the ROI’s waters. Four transatlantic cables land on the ROI’s shores, and 12 connect the ROI to the UK, in most cases before extending onwards to the European continent.73Submarine Cable Map. Aside from the general importance of cables to a state’s social, political, economic and military systems, the ROI’s finance and tech-dominated economy renders its economic model even more dependent on these undersea networks. Indeed, the government’s strategy for economic growth is predicated entirely on digital data transfers along undersea cables, folded into the ambition to make Ireland the central digital hub in the East-West corridor.74International Connectivity for Telecommunications Consultation – Key Findings 2021, Irish Dept of the Environment, Climate and Communications, 2021, 15. Technology allows adversaries to sabotage these cables – both with rudimentary physical damage, and cyber-attacks – and to tap them with listening devices, enabling data to be collected and decoded. Due to the interconnected nature of the global financial system and tech sector, disruption to Irish infrastructure would have massive knock-on effects for other states integrated in the international free market and US-led order.