Authors

Content

Foreword

Lord Pickles

Former Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government

For decades, litter has been at the forefront of public concerns about people’s local areas. This should come as no surprise when 2 million pieces of litter are dropped every day across the country, equating to 23 pieces of litter per second.

There are enormous costs to the growing scourge of litter – to the taxpayer, to the environment and to the beauty of our countryside and neighbourhoods. It costs the taxpayer over £1 billion a year – money that could be spent on other vital public services. The RSPCA have also stated that they receive an average of 14 calls a day regarding wildlife harmed by litter. And, of course, there is the depressing fact that the more litter there already is in an area, the more likely people are to make the problem worse.

It is for these reasons that, as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, I endeavoured to offer practical solutions to address the scourge of litter. In 2015, I was proud to launch the first ever Community Clear Up Day, which saw communities across the country coming together to clean-up litter. Additionally, in order to discourage fly tipping and littering I oversaw the Weekly Collection Support Scheme, which allocated £250 million to support councils in their delivery of a weekly bin collection.

Of course, most communities take pride in their public spaces: high streets should aspire to be hubs of economic activity, with thriving streets reflecting the character of the local area. If we are serious about levelling-up and restoring pride of place, a popular, logical step would be to reduce litter to enhance the beauty of our local spaces – making them an attractive proposition for local communities to visit.

This paper makes a timely contribution to this important issue, where too many local authorities are not enforcing the law. Measures to drive behavioural change such as introducing a digitised Deposit Return scheme and rewarding sustainable change on the part of companies that manufacture and produce packaging are all remedies that could make a difference, particularly when combined with more substantial fines, consistent enforcement and a Council League Table to show which local authorities are gripping this problem. Addressing litter and the physical environment gives the clearest signal that a local authority respects its residents.

Significant intervention on this issue is long overdue.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

Litter is ugly and an overwhelming majority of Britons want action. Since the 1960s littering has increased by 500%. Years of inaction, compounded by a lack of personal responsibility and a sharp increase in littering during the COVID-19 pandemic has made the problem worse.

Policy Exchange first recommended a national and coordinated approach to litter in Litterbugs published in 2009, but it was not until 2017 that the Government published the first ever national strategy that dealt with litter and littering behaviour. Furthermore, in 2022 the Office for Environmental Protection has said that the Government has yet to move beyond mere commitments to policy delivery.

The economic impact and cost of littering in the UK is £1 billion. Approximately 730 million items are littered annually with each piece of litter costing the UK economy 73p on average. Fly-tipping, a more serious form of littering, is also on the rise. Local authorities in England dealt with 1.13 million fly-tipping incidents in 2021, an increase of 16% from the previous year, as local recycling centres closed during the lockdown when people embarked on DIY and home improvement projects.

In addition to the economic cost, littering has a far-reaching environmental impact in both marine and natural environments. Roadside litter alone kills approximately 3.2 million shrews, voles, and mice every year. Moreover, contaminants released from the breakdown of litter are a human health risk as micro- and nano-plastics become embedded in foods we eat – with one study finding 100% of mussels collected from the UK coastline and supermarkets contained microplastics and other debris.

The cleanliness of streets and local areas strongly correlates to levels of deprivation and affluence. The most affluent neighbourhoods showed above levels of acceptable cleanliness whereas some of the most deprived contained seven times as many small non-plastic bottles and three times as much litter more broadly. Heavily littered areas appear ignored, undervalued, and not cared for, which can lead to even more littering behaviour just as neighbourhoods with graffiti and broken windows generate more crime in local areas.

Despite this serious and growing problem, too many local authorities are not making good use of the powers available to them. Littering is a criminal act, punishably by a fixed penalty notice of up to £150. For fly-tipping, a person is liable to imprisonment of up to 12 months and/or a £50,000 maximum penalty. Yet of the 169 councils that responded to a series of Freedom of Information requests issued by the charity Clean Up Britain, 56% were issuing less than one fine per week and 16% of councils were issuing no fines at all. For fly-tipping, last year saw the lowest levels of enforcement since 2014.

For the restoration of a sense of community, local pride, and belonging, there is a clear and unavoidable need to address littering. This report calls for the Government to implement a new and revitalised Litter Strategy, including a significantly more aggressive approach to fines, including higher penalties, with a Local Authority League Table to name and shame those councils that are not using their powers; a new National Litter Awareness Course (modelled on the National Speed Awareness Course), backed by educational campaigns, to transform attitudes to personal responsibility; increased investment in bin infrastructure, with consideration of bins embedded in local design codes; and a large scale pilot of a digitised Deposit Return Scheme to enhance recycling.

If implemented, these recommendations will allow us to reverse the growing tide of litter and make Britain, once again, a cleaner, greener and tidier land.

Next chapterPolicy Recommendations

Fines and Enforcement

- Triple the level of fines. At present, the default level of fines for a littering offence does not reflect the scale of the litter problem in the UK and is notably smaller compared to other ‘on the spot’ fines or criminal acts. Tripling the level of fines significantly increases the deterrent effect and personal cost of a litter offence.

- Council League Table. A lack of enforcement generates a cultural understanding that littering, whilst frowned upon, is trivial – despite being a criminal offence. A league table, published as part of DEFRA’s ‘Litter Dashboard’, would rank local authorities on how actively they use their powers to tackle litter and littering behaviour. A league table would incentivise councils to develop local litter strategies, enable residents to hold councils to account, as well as instil a competitive spirit across regions and between metro-mayors.

- A National Litter Awareness Course. Just like the National Speed Awareness Course that teaches the dangers of speeding and dangerous driving, a litter awareness course offers a chance to re-educate and change behaviour as an alternative to prosecution and fines. It would directly target the worst offenders. The National Litter Awareness Course would provisionally be priced between £80 to £120, the same as the National Speed Awareness Course. As this would be significantly lower than the new default fine, this would provide an incentive to people to take the course.

Education and Campaigns

- New campaign to make littering socially unacceptable. This should be channelled through existing anti-littering groups, which are trusted by the public. Public funding, however, has declined with central Government withdrawing financial support as part of budget cuts in 2010. Such a campaign should target the youth and reinforce personal responsibility – if individuals wish to use and enjoy public spaces, respect for these environments should be paramount.

Binfrastructure

- Embed the provision of bins and ashtray in strategic sites within design codes. The provision of bins is largely absent from designs codes, including the National Planning Framework. Mandating bins in design code enables a dialogue between local authorities and private developers ensuring better place making and local development, as well as balance the provision of bins between the private and public sector. It should also promote a more unified public realm design strategy where litter bins are discreetly incorporated into other elements of street furniture, such as bus stops, benches, and lampposts. Not only would this provide more opportunities for litter disposal but it would also encourage a cleaner, more streamlined visual landscape reducing litter and street clutter.

- Re-run the Binfrastructure Capital Grant Fund but allocated by formula. The placement and provision of bins and ashtrays is necessary and important; however, the last round of funding saw low participation by local authorities. Rather than local authorities bidding for funding, allocation by formula is more time effective, enabling local authorities to focus on delivery, with local authorities needing only to demonstrate proof of installation to draw down funds. In conjunction with the first recommendation, more funding provides an opportunity for local authorities and regions to be proactive and compete on the Council League Table.

Two Schemes: Deposit Return Scheme and Extended Producer Responsibility

- Large scale pilot of a digitised Deposit Return Scheme. A digitised component of the Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) would make use of existing bin infrastructure and collection points, as well as accommodate for future technological innovation, such as ‘smart’ on-the-go bins that can be retrofitted. It is an app-based approach and an alternative to installing Reverse Vending Machines across the country. Digital DRS presents various challenges as an emerging technology. As such, given the technology’s significant cost saving potential, a large-scale trial should take place.

- Explore and reward sustainable change. Private sector innovation will play an essential role in reducing waste and litter. Companies that explore and implement policies and/or changes to manufacturing, production and packaging processes that result in large scale reductions in waste must be rewarded. The Government should ask and consult businesses that sell consumer goods which rewards work best to drive innovative sustainable change.

Two Heavily Littered Items: Butts and Gum

- Zero-rate VAT on biodegradable gum. For heavily littered items that dirty streets and pavements, the Government should support the business case for biodegradable products, especially in the case of chewing gum and cigarette butts. Alternative biodegradable chewing gum products are roughly three times more expensive than single use plastic chewing gum. As such, the Government should introduce a zero-rate VAT on biodegradable plant-based chewing gum.

- Ban synthetic cigarette filters. Synthetic cigarette filters do not biodegrade and can last up to fifteen years in the environment. The Government should ban synthetic filters, requiring cigarette manufacturers to switch back to pre-World War Two methods of using cotton and wool.

Introduction

Litter is ugly. It is an unsightly and an environmentally damaging by-product of modern development and society. Between the 1960s and 2009, littering has increased by approximately 500%.1Policy Exchange. (2009) Litterbugs: How to deal with the problem of littering. Link When asked about improving the beauty of local areas, litter trumps crime, vandalism and graffiti as the most important local issue to the British public.2Ipsos. (2015) Litter and crime the most important aspects in making the local area a beautiful place to live. Link Frequently, both national and local politicians partake in litter picking operations in their local areas, attesting to the strong public sentiment against litter.

Policy Exchange first highlighted the litter problem in 2009 with the publication of Litterbugs.3Policy Exchange. (2009) Litterbugs: How to deal with the problem of littering. Link With a Foreword by Bill Bryson OBE, then President of the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE), the report argued that a lack of co-ordination to disseminate information and best practice had failed to alter social norms. Previous anti-littering attempts were too disjointed, inconsistent, and localised. The media coverage of Litterbugs was extensive, with Bryson appearing on broadcast media to discuss the report, as well as national and international press coverage.4Litterbugs was reported in the Telegraph, the Guardian, Independent, and even the Times of Malta The principal recommendation of Litterbugs was a coordinated approach by central government to tackle the UK litter problem.

Since the report was published, the battle against littering endures. Despite the media attention and public debate that followed, it was not until 2017 when the Government launched its first ever national approach to tackling litter. The Litter Strategy highlights that “a littered environment is bad for our wellbeing, and bad for the economy” and set out 36 commitments aimed at cleaning up the country and delivering a substantial reduction in litter and littering within a generation.5HM Government. (2017) Litter Strategy, p.9. Link As a first attempt, the strategy enjoyed little opposition and was welcomed by a broad range of campaign groups and organisations; perhaps a reflection of the unanimous feeling of disgust that unsightly litter arouses in the passer-by.

The Litter Strategy, however, faltered with Covid-19 pandemic. The annual progress reports for 2019-20 and 2020-21 were not published. The Government recognise the pandemic’s impact in the battle against litter. Various initiatives and campaigns were either downsized or postponed, whilst at the same time, lockdowns led to a ‘litter epidemic’ in public spaces. Nonetheless, the litter problem persists, and the pandemic is now long gone. The time is ripe for the Litter Strategy to undergo a complete reboot with existing policies revitalised, new ideas embraced, and a greater emphasis on personal responsibility. If not now, when?

Crucially, the starting premise of a rebooted Litter Strategy should acknowledge that individuals litter and so individuals are responsible for their immediate impact on the environment. Correctly binning an item of litter is something everyone can do. The Government can only do so much in waging the war against the litter that plague our streets and public spaces. To alleviate the burden on Government and local authorities, the British public must first take responsibility, collectively change social norms, and properly dispose of its rubbish.

The subsequent paper is a revival of Policy Exchange’s original Litterbugs report albeit with fresh analysis and a re-evaluation of the battle against litter. It is structured as follows:

- Chapter One: Why Tackle Littering? – Tackling litter is important for many reasons. The chapter discuses four reasons including the general consensus of public opinion, environmentalism, as well as how solving the litter problem is crucial to the Government’s Levelling Up agenda to restore pride of place, and finally, the newly established regulatory body, the Office for Environmental Protection.

- Chapter Two: The Litter Problem – This chapter outlines the problem of litter in the UK and covers its history, Policy Exchange’s original contribution to the debate, and how Covid-19 both exacerbated the issue and derailed the Government’s Litter Strategy.

- Chapter Three: Existing Policies Revitalised and New Ideas Embraced – Fresh analysis of existing policies and some new ideas are discussed in this chapter. Policy recommendations are addressed thematically, including fines and enforcement; education and campaigns; binfrastructure; a deposit return scheme and extended producer responsibility; and finally, two heavily littered items including plastic gum and synthetic cigarette filters.

- Chapter Four: Summary of Policy Recommendations – this chapter summarises the paper and the policy recommendations that it proposes.

Chapter One: Why Tackle Litter?

The litter problem is important for many reasons, including the aesthetics and beauty of places; the impact on the environment; and its impact on local pride. The UK has a long and vibrant history of environmentalism, benefitting from the activism of notable figures such as the broadcaster and natural historian, Sir David Attenborough, and of the late Duke of Edinburgh with both his son, King Charles III, and grandson, the Prince of Wales, continuing his life’s work and legacy. Moreover, as climate change has become an issue of international importance, environmentalism has evolved and grabbed the attention of policy makers and politicians, as well as the general public. Solving the problem of litter must play its part in making our urban and rural environments greener, more beautiful, and healthier places.

1. Aesthetics & Beauty

Almost everyone wants to live in a beautiful place. This might be an idyllic rural village, a sleepy suburb, or a smart inner-city square, terrace, or mansion block. It will require pleasing architecture, quality street and pavement surfaces, appropriate streetlights, and other street furniture including trees, bushes, hedges, and other greenery. But all of this can be spoiled by litter, which is universally believed to be ugly.

Among all the features that enhance or detract from urban beauty, many Britons think that ‘less litter and rubbish’ is the most important factor in determining the overall aesthetic quality of a place.6Harvey, Adrian and Caroline Julian. (2015) ‘A Community Right to Beauty: Giving communities the power to shape, enhance and create beautiful places, developments and spaces’, ResPublica, p. 24. Link Litter makes a neighbourhood appear forgotten, neglected, and loutish. Crisp packets, takeaway packaging, and plastic bottles can ruin the prettiest of sceneries, and cigarette butts and chewing gum can dirty streets and pavements into something repellent. Litter can also have knock-on impacts: individuals are less likely to litter in clean areas, whilst dirty areas can quickly become litter hot-spots.7Keizer, Kees., Siegwart Lindenberg, and Linda Steg. (2009) ‘Contagious Crime’, Wilson Quarterly. Link A heavily littered area seems like it is ignored, undervalued, and not cared for, which can end up leading to even more littering behaviour, in the same way that neighbourhoods with graffiti and broken windows seem to generate more crime.8Corman, Hope., and Naco Mocan. (2005). ‘Carrots, Sticks, and Broken Windows’, The Journal of Law and Economics, 48(1), pp.235-266. Link The problem of litter in the UK bears great semblance to Wilson and Kelling’s ‘Broken Windows Theory’ and its central premise that each problem left unattended in a given environment affects people’s attitude toward that environment and leads to more problems, or in this case, more litter.9Kelling, George and James Wilson. (1982) ‘Broken Windows: The police and neighbourhood safety’, The Atlantic. Link

Urban beauty has long been a focus of Policy Exchange’s work with the Building Beautiful programme leading the debate on empowering communities and creating beautiful urban spaces.10Policy Exchange. (2019) Building Beautiful. Link Building Beautiful has consistently argued for the importance of strong architectural design and urbanism, most recently in Strong Suburbs and A Call for Tall Buildings Policy.11Policy Exchange. (2021) Strong Suburbs. Link 12Policy Exchange. (2022) A Call for Tall Buildings Policy. Link These papers have offered policies that translate the aspiration and desire of urban beauty into actionable ideas and policies. There are, however, many other kinds of ugliness in our built environment that need to be tackled and litter is one of them. Tackling litter is an easy, obvious, and unifying issue that enhances not just urban, but also rural beauty. One recent poll saw 81% of people say they felt angry and frustrated by the amount of litter all over the country.13Populus. (2015) Public Perception on Litter in the UK. Successive governments have made steps to try and tackle the litter problem, most recently in the 2017 with the UK Litter Strategy. But despite some progress, much of the problem remains.

2. Environmental Impact

Littering has a far-reaching environmental impact in both marine and natural environments and is well documented. For instance, the breakdown of plastics found in litter can pollute the environment by releasing micro- and nano-plastics via runoff into the soil and nearby water courses, causing degradation and damaged ecosystems.14Andrady, Anthony. (2011) ‘Microplastics in the marine environment’, Marine Pollution Bulletin. Link This is released into the environment through in situ weathering, most notably via sunlight in the beach environment, and into the marine ecosystems.15Ibid The consequent transfer of chemicals has knock-on consequences for marine ecosystems, including chemicals that disrupt animal hormone production, impair reproduction resulting in lower birth rates, and the eventual loss of biodiversity.16Gallo, Frederic., Cristina Fossi et al. (2018) ‘Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: the need for urgent preventative measures’, Environmental Sciences Europe. Link Microplastics alone have been found in more 100 marine species surveyed and ingested by over 80% of sample populations. 17Ibid Moreover, animals can also become entangled in bigger plastics before degradation and can die through ingesting litter. In the UK specifically, it is also estimated that roadside and lay-by littering could be killing up to 3.2 million shrews, voles, and mice every year. 18Keep Britain Tidy. (2018) Journal of Litter and Environmental Quality. Link More than 8% of bottles and almost 5% of cans collected as part of an area study in Norfolk contained the remains of some of our smallest mammals. These small mammals play an essential role in our food chain from eating insects and plants, and then acting as prey for other animals and birds.

The littering of plastics is also a human health risk. Microplastic contamination, as a result of plastic leakage into the environment, can eventually re-enter the human body via the food chain.19UNISAN. (2020) How does litter harm the environment. Link A 2018 study found 100% of mussels collected from the UK coastline and supermarkets contained microplastics and other debris.20The Independent. (2018) All UK mussels contain plastic and other contaminants, study finds. Link It is currently unclear how significant microplastics pollution is for human health.21The New Statesman. (2021) Is pollution really causing penises to shrink and sperm counts to plummets? Link There is an active debate among scientists and governments, but previous pollutants, such as lead, were later discovered to have enormous effects on human health and behaviour.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic adversely impacted that extent of litter found in the UK environment, further exacerbating the problem. One group of academics found that among the 11 countries studied, the UK showed the highest overall proportion of littered masks, gloves, and wipes as litter, with masks alone accounting for 5% of all litter.22The countries studied include Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. This peaked to 6% when restrictions were eased.23Roberts, Keiron., and Sui Phang et al. (2022) ‘Increased personal protective equipment litter as a result of Covid-19 measure’, Nature Sustainability. Link One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the burden on local authorities to deal with staff absences and new working practices leading to reduced street cleaning and bin collection services. Another explanation could be the UK’s social disposition and attitude towards littering, and a pre-existing failure to shift societal norms and littering behaviour. The impacts of littered masks, gloves, and wipes are numerous, including an increased potential of blockages in sewerage systems, megafauna and animals being entangled in straps and elastic used in PPE, as well as becoming a vector for pathogens and pollutants. The severity of the UK with the highest proportion of Covid-19 related litter correlates to the differences in waste manage practices and embedded littering behaviours before the pandemic. The UK is the worst among our allies and comparable countries, such as France, the United States, Germany, and Australia.

3. Local Pride

The relationship between litter and socio-economic status is one of correlation not direct causation. The Government’s 2014/15 Local Environmental Quality Survey of England, conducted by the charity Keep Britain Tidy, found that those areas with more indicators of deprivation have markedly higher levels of litter. Reasons for this correlation are complex and unclear. However, the extent of litter and sites deemed ‘unacceptably tidy’ falls from 25% in the most deprived areas to 2% in the least deprived areas.24Keep Britain Tidy. (2015) The Local Environment Quality Survey of England 2014/15. Link This finding aligns with an earlier study which first highlighted the correlation back in 2009 and outlined some of the characteristics of heavily littered neighbourhoods.25Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2009) Street cleanliness in deprived and better-off neighbourhoods. Link The extent of litter is greater in areas with smaller dwellings and high-density housing; properties without gardens; more mixed-use properties; disused buildings; more young adults; and finally, certain types of street layout, such as thoroughfares across a city. In order to break this correlation, Government policy and local authorities must focus on and target deprived areas if it is to achieve its levelling-up ambitions and restore pride in place for local residents across the entire country. There are three references in the Government’s Levelling Up White paper to litter, including high street rejuvenation; sentencing of offenders by tasking them with street cleaning and clearing litter; and perhaps more importantly, restoring a sense of community, local pride and belonging.

| Littering in Denmark |

| Denmark is ranked the world’s cleanest and most environmentally friendly country, with an overall Environmental Performance Index score of 77.9, and a waste management score of 68.3.26Environmental Performance Index. (2022) Denmark. Link Its capital, Copenhagen, ranks second only to Zurich as Europe’s cleanest city.27The Local. (2015) Copenhagen is Europe’s second-cleanest city. Link Pro-active anti-littering campaigns have helped Denmark tackle the issue better than others. For instance, the Pure Love litter-prevention campaign run by the city of Copenhagen between 2012-2015 with a particular aim of ‘nudging’ to encourage individuals to help keep the city clean.28Clean Up Europe Network. (2016) Nudging: From Denmark with Love. Link ‘Nudging’ is be understood as a policy which makes it simpler and easy to do the right thing. Bright green trails directed individuals to bright green bins marked with ‘save our planet’ which were placed all around the city. The government also provided over 300 cafes and restaurants with portable ashtrays to reduce cigarette litter. On beaches around Denmark similar portable ashtrays were also provided. Mini trash-bags were also handed out for free. The positive pro-active campaign created and helped reinforce positive feedback loops as citizens start to take an interest and pride in keeping Denmark Europe’s cleanest country.

Denmark also has a notable coastline with beaches often littered due to high winds. In 2012 the government of Denmark launched the Danish Marine Strategy to improve the environmental quality of its beaches.29Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. (2019) Danish Marine Strategy II. Link Multiple organisations were involved, such as the NGOs, KIMO Denmark collaborating with Arhus University’s National Centre for Environment and Energy, to monitor progress and inform the strategy.30KIMO. (2019) Monitoring beach litter in Denmark. Link One particular challenge faced by Denmark is the source of its beach litter occurring from other countries, especially those bordering the North Sea. It illustrates the need for countries around the North Sea to work together and coordinate action through the EU Plastics Strategy. |

Chapter Two: The Litter Problem

This chapter outlines the problem of litter in the UK. There are several dimensions to the litter problem. These include the scale and costs associated with littering, and the history of littering as a disjointed, inconsistent, and localised problem that requires a national strategy. After years of inaction, the Government launched the first ever national litter strategy, but even then, the Covid-19 pandemic derailed it.

1. The Scale and Cost of Littering

Between the 1960s and 2009, littering increased by approximately 500%.31Policy Exchange. (2009) Litterbugs: How to deal with the problem of littering. Link The headline fact of Keep Britain Tidy, the UK’s anti-littering campaign group, is that “more than two million pieces of litter are dropped in the UK every day. The cost to the taxpayers for street cleaning is over £1billion a year.” 32Keep Britain Tidy. Litter and The Law. Link These are extraordinary and alarming figures. 730 million items are littered annually with each piece of litter costing 73p to the taxpayer on average. This trend has and continues to grow significantly. For the 2020/21-year, local authorities in England dealt with 1.13 million fly-tipping incidents, an increase of 16% from 2019/20, two thirds of which involved household waste. Total incidents involving household waste rose by 16% from 2019/20 to 2020/21.33HM Government. (2021) Fly-tipping statistics for England, 2020 to 2021. Link According to the most recent and extensive survey by Keep Britain Tidy, smoking related litter was visible at 73% of sites and 92% of industry, warehouse, and retail sites.34Keep Britain Tidy. (2015) The Local Environmental Quality Survey of England 2014/15. Link Specifically relating to fly-tipping, the Government has recently opened a consultation on DIY waste, which proposes that households should not be charged for disposing of DIY waste.35DEFRA. (2022) Government announces new crackdown on fly-tipping. Link

Cigarette butts comprise 66% of all littered items, but only 0.2% of overall litter volume.36Keep Britain Tidy. (2020) Litter Composition Analysis. Link Small plastic bottles and non-alcoholic cans make up 43% of litter volume but 3% of littered items. This indicates that size matters because the smaller and more discrete the item, such as cigarette butt or chewing gum packaging, the more likely it is to be littered. These are conspicuous and frequently consumed ‘on the go’ items with less stigma attached to being littered. Branded items and large household names are also significant: McDonald’s is the most often occurring culprit, followed by Coca-Cola and Wrigley’s Extra chewing gum packaging.37Ibid

Street cleaning cost local authorities £778m in 2015/16. The most recent figure is unknown and likely to be higher given current trends of littering and the impact of COVID-19. As already mentioned, Covid-19 has exacerbated the littering problem, but also increased the cost to local authorities. In the immediate months following the first easing of Covid restrictions, local authorities spent on average an extra £33,000 managing littering and anti-social behaviour in local parks with on average an additional 57 tonnes of waste per council.38Keep Britain Tidy. (2020) New Campaign Launched in Face of Littering Epidemic in Parks. Link One council even reported a spending increase of £150,000 as people flooded to public spaces to get fresh air while shops, restaurants and pubs were closed.39Ibid Keep Britain Tidy warned of a ‘littering epidemic’ as lockdowns were eased.40BBC. (2020) Why litter is surging as lockdown ease. Link The use of plastic packaging in takeaways and online deliveries, masks, and other PPE, has meant more plastic packaging refuse in public spaces.41Ibid Whilst this could be a result of ignorance, as people socialise outside instead of at home, or in pubs and restaurants, there may also be a psychological component. Some research suggests that the stressful experience of the pandemic has reduced the salience of littering.42Ibid

Prior to the pandemic, the Government recognised the littering cost to local authorities and stated that “a significant portion of this will have been avoidable… [and] better spent on vital public services.”43HM Government. (2017) Litter Strategy. Link This report identifies how the cost-saving could be better achieved by rebooting the Government’s Litter Strategy with existing policies revitalised and new ideas embraced. The public conscience needs a reawakening to the litter problem as Covid-19 has bred complacency and demonstrates a lack of behavioural change the Government’s Litter Strategy aspired towards.

The newly established Office for Environmental Protection (OEP), created as a statutory regulatory body by the Environment Act 2021, aspires to “provide independent oversight of the Government’s environmental progress.”44Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. (2021) Interim Office for Environmental Protection to be launched. Link Recently, it called on the Government to do more, noting that progress had been slow. The OEP argued that the Government’s vision needed to be “underpinned with effective strategy, policy and delivery mechanisms; and strong leadership, better governance and effective monitoring.”45Office for Environmental Protection. (2022) Taking stock: protecting, restoring, and improving the environment in England. Link In Defra’s response to the OEP challenge, there was much agreement from the Department stating that it will revise ‘legacy targets’, conduct a five-year Significant Improvement Test and publish the next Environment Improvement Plan by January 2023 to “drive outcomes and focus on delivery”.46Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. (2022) Defra response to OEP report: Taking stock: protecting, restoring and improving the environment in England. Link On the topic of litter, however, the OEP notes that despite the Government’s target to deliver a substantial reduction in litter and littering behaviour within a generation only remains a commitment with an unspecified deadline. The 2017 Litter Strategy is the only policy document which underpins the problem of litter, and as argued below, requires a reboot with existing policies revitalised and new ideas embraced. In doing so, the Government can prove to the OEP that it is moving beyond mere commitments with substantive policy ideas that are deliverable and will significantly reducing levels of litter.

2. The History of the Litter Problem

Policy Exchange’s Litterbugs report was published in 2009. It argued that whilst an important and more complex issue than generally perceived, “litter can be reduced if we develop and implement a coordinated national strategy and draw on better design, develop long-term educational campaigns, share best practice and create mechanisms that change people’s behaviour for the better.”47Policy Exchange. (2009) Litterbugs: How to deal with the problem of littering. Link Despite the media attention and public debate that followed the publication of Litterbugs, little was done by Government until 2017 with the launch of the Litter Strategy. The Litter Strategy recognised Litterbugs’ central argument and supported some of the report’s original policy recommendations, such as a Deposit Return Scheme (DRS). Commendably, the Litter Strategy was the first ever national approach that addressed the UK’s litter problem. Litter, especially clearing it off our streets, has always been a devolved responsibility and delegated to local authorities. The strategy was welcomed because reducing littering and its cost to local authorities requires central Government support and a national effort to bring about societal and behavioural change. However, as demonstrated in the table below, comparing Litterbug’s original policy recommendations and progress since its publication 13 years ago highlights that more work is required to minimise litter and solve the UK litter problem.

| Litterbugs Policy Recommendations | Developments since 2009 |

| The re-establishment and reform of ENCAMS as the national body responsible for coordinating anti-littering initiatives, campaigns, and programmes.

ENCAMS is unable to fulfil such a role because its funding base is too small. |

The charity ENCAMS changed its name back to Keep Britain Tidy in 2009 and expanded. In 2011 it merged with Charity Waste Watch.

Keep Britain Tidy has become the pre-eminent charity in campaigning and producing research in the battle against litter. In 2020/21 the charity received £1.7m from local authorities to provide advice and campaign material. It also received £0.1m in grants from central Government.48Keep Britain Tidy. (2021) Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31st March 2021. Link |

| The development of a permanent educational campaign with a consistent message to target littering. | Keep Britain Tidy runs a plethora of campaigns and initiatives, and works with multiple groups in society, such as schools in the ‘Great Big School Clean’. 49Keep Britain Tidy. Great British Spring Clean. Link

Some campaigns take place on an annual basis, such as the ‘Great British Spring Clean’, however there is no permanent campaign that happens throughout the year. |

| The provision of bins and ashtrays in strategic sites. | ‘Binfrastructure’ featured as a key element in the Government’s Litter Strategy in 2017. The Government enlisted the help of WRAP to produce guidance for local authorities.50WRAP. (2020) Binfrastructure’ – The right bin in the right place. Link

There existed a capital grant for the purchase of litter bins open to local authorities but this saw low take-up. Some tobacco companies provide free ‘portable ashtrays’.51UK Parliament. (2015) Communities and Local Government Committee, oral evidence 6th January 2015. Link |

| The introduction of a national deposit scheme. | In March 2021 a consultation on a DRS closed and DEFRA is yet to publish its response.

The Welsh Government concluded a pilot scheme and aims to implement DRS by 2024. The Scottish Government has delayed its DRS citing a decision by the UK Government not to cancel VAT within the scheme.52The Herald. (2021) UK Government ‘profiting’ from Scotland’s deposit return scheme amid VAT row. Link |

| Taking account of litter and littering behaviour in the design of our public spaces. | The National Design Guide only mentions bin stores that should “not be visible from the street” and refuse bins used for rubbish collection.53HM Government. (2021) National Design Guide. Link

There is no provision or guidance for the strategic location of public bins and littering behaviour within national design codes. |

| Greater consistency in the application of penalties for littering across local authorities. | Some campaign groups are calling for fines to increase from £150 to £1,000.

A FOI by Clean Up Britain showed 56% of councils issue less than one fine a week. 54Clean Up Britain. (2020) Don’t Trash Our Future. Link |

| The creation of a new Environmental Advisory service to promote effective knowledge sharing about littering. | No such service exists that has a specific remit for the UK’s litter problem. Keep Britain Tidy is one of the pre-eminent charities within the sector and partially resembles this recommendation. |

| Key to table above | |

| Policy implemented | |

| Partially implemented/further work required | |

| Outstanding | |

Like Litterbugs, the Government’s Litter Strategy acknowledged that Britain suffers from too much litter, causing environmental, aesthetic, and safety problems. It forms part of the Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan launched in 2018 that aspires toward a “a cleaner, greener country for us all.”55HM Government. (2018) A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment. Link To this end, the UK Litter Strategy proposed a three-pronged approach.

Education and awareness: educating youth not to litter and encouraging businesses to run their own anti littering campaigns.

Improving enforcement: tightening enforcement measures against littering by raising fixed penalties and giving councils new powers to local authorities to tackle it themselves.

Better cleaning and litter infrastructure: working with producers to improve the provision and ease of waste disposal and researching improved packaging design.

A new metric was also proposed to ensure the Government achieves its goals with the development of a ‘dashboard’ aimed at presenting a “richer picture of litter and its impacts… and potentially also covering tackling litter, perceptions, and enforcement.”56Ibid, p.18 The dashboard never materialised but the Government did provide annual progress reports on the 36 commitments in the original strategy document. Progress reports were published in the first three years of the Litter Strategy. Recognising the impact of COVID-19, however, the 2019-2020, 2020-21 and 2021-21 reports were not published annually but amalgamated in one report earlier this year. The Government also stated: “We will therefore reflect on whether the commitments need refreshing … this [the progress report] will therefore be the last annual report that sets out progress against the litter strategy in its current form.”57HM Government. (2022) Litter strategy for England: annual report (2019-2022). Link

The outcomes of the 36 commitments varied. Many are ongoing commitments. Few have been completed or recently superseded by other commitments. Progress, therefore, since the Government’s Litter Strategy has been largely unsuccessful and patchy. Moreover, the last Local Environmental Quality Survey of England, carried out by Keep Britain Tidy, was last published for the year 2019/20 and only was seven pages long. It contrasts to previous surveys that were more comprehensive, such as the 2014/15 year which explored litter’s correlation with affluent and deprived areas.58Keep Britain Tidy. (2015) The Local Environment Quality Survey of England 2014/15. Link As a result, it is difficult to discern the extent of the UK’s litter problem.

Solving this problem involves resurrecting and revitalising existing policies as well as some completely new ideas.

| Littering in Singapore |

| Singapore is renowned for being Asia’s greenest and cleanest metropolis. Three years after its independence, Singapore’s ‘founding father’ and first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, launched the Keep Singapore Clean in 1968. For over five decades the Singaporean government has campaigned and legislated against littering persuading its citizens to keep the sovereign city-state clean. Those who reside in Singapore are thus not unfamiliar but highly socialised with regular cleanliness campaigns and the prohibition of heavily littered items. For instance, in 1983 the Government launched the Keep the Toilet Clean Campaign. In 1992 the importing and sale of chewing gum was banned. Moreover, rubbish trucks are perfumed as a testament to Singapore’s admirable enthusiasm toward hygiene.

There is also a clear public health dimension to tackling litter in Singapore, particularly given its tropical climate. High temperatures and humidity create the ideal conditions for rodents, flies, and cockroaches to breed. In Singapore, it is recognised that if left on the streets for long periods of time uncollected, household and business rubbish presents a risk to public health. In Lee Kuan Yew’s inaugural speech of the Keep Singapore Clean campaign, he stated:

|

Chapter Three: Existing Policies Revitalised and New Ideas Embraced

The following chapter offers a fresh assessment of existing policies as well as new ideas. Policies options are addressed thematically in the subsequent order:

- Fines and Enforcement

- Education and Campaigns

- Binfrastructure

- Two Schemes: A Deposit Return Scheme and Extended Producer Responsibility

- Two Heavily Littered Items: Chewing Gum and Cigarette Butts

From this discussion and analysis, eight policy recommendations are put forward for the Government to reboot its strategy in the battle against litter. These recommendations are broadly underpinned by incentivising change and challenging littering behaviour, opting for less intrusive measures such as installing CCTV cameras in litter hotspots and emphasising personal responsibility.

Fines and Enforcement

Littering is illegal in the UK. As per the Environmental Protection Act 1990, to throw down, drop or otherwise deposit and leave litter in any place that is open to air, including private land, is a criminal offence. There is no statutory definition of what constitutes litter, but the courts have commonly adopted a wide definition, such as “…miscellaneous rubbish left lying about. Rubbish left lying about can consist of all manner of things including domestic household waste, commercial waste, street waste and not doubt other waste not falling within such description.”60The Countryside Charity. (2020) Litter Law. Link The Environmental Protection Act 1990 does specify two specific items, notably cigarette butts and chewing gum. If caught littering, an individual can be issued a Fixed Penalty Notice (FPN). Following the Government’s Litter Strategy, the FPN was raised from a maximum of £80 to £150. At present, the default is £100 and the minimum is £65. An individual can challenge the litter offence in court and, if prosecuted, a maximum penalty of £2,500 can be imposed. For fly-tipping, a more egregious form of littering, a person is liable to imprisonment of up to 12 months and/or a £50,000 maximum penalty. The Environmental Protection Act 1990 empowers a wide range of public officers to catch a litter offender. These include street scene operators, local authority enforcement officers, wardens, as well as police officers, who are also required to receive training.

Despite fairly robust legislation and an enforcement code of practice published by DEFRA,61Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. (2022) Effective enforcement: Code of practice for litter and refuse. Link there exists an enforcement problem as local authorities do not readily use their powers. Enforcement has been described as a ‘litter lottery’ with notable variation between local authorities issuing fines. Data and statistics on litter enforcement are not readily available or made public. As such, whilst it is difficult to discern a comprehensive picture, campaign groups have demonstrated that local authorities do not readily use their existing powers and enforce the law on litter. Of the 169 councils that responded to a series of Freedom of Information requests issued by the charity Clean Up Britain, 56% were issuing less than one fine per week and 16% of councils were issuing no fines at all.

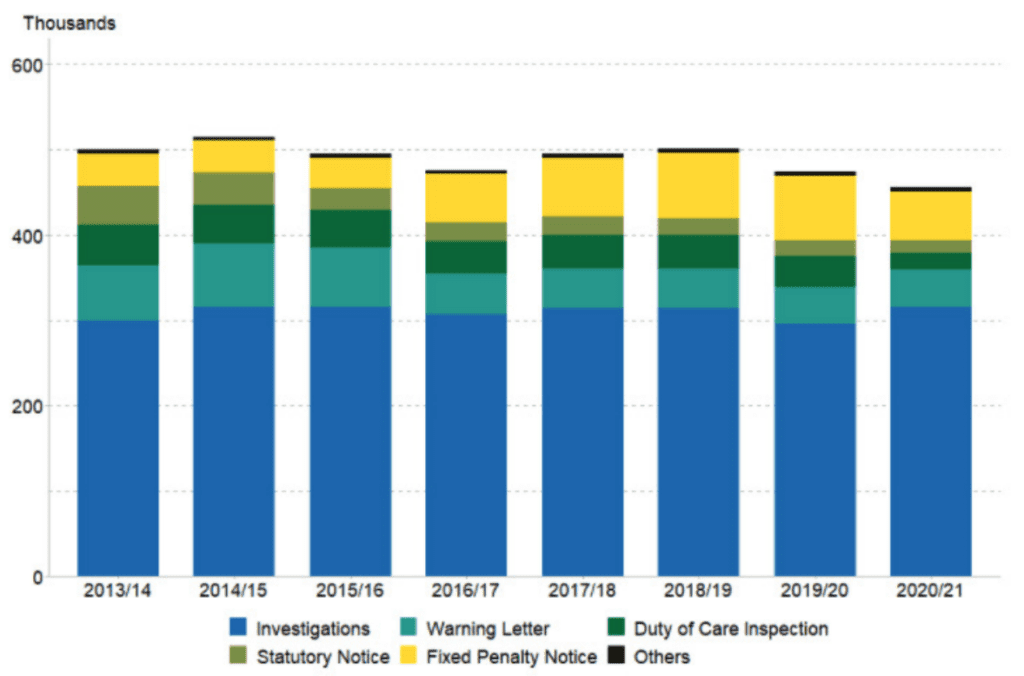

On fly-tipping, however, national data is collected and published by DEFRA. The law makes the distinction between littering and fly-tipping, with the latter considerably larger by volume, such as a black bin bag or dump truck of rubbish. Again, however, fly-tipping trends are far from positive. Last year local authorities dealt with 1.13 million fly-tipping incidents, an increase of 16% from the previous year.62HM Government. (2021) ENV24 – Flying tipping incidents and actions take in England. Link This increase was met with the lowest levels of enforcement since 2014 (see Table 1).

Litter offenders simply do not think that they will get caught due to a lack of enforcement. Offenders rarely hear of others being caught or are rarely caught themselves despite littering being a criminal offence. To overcome this enforcement problem there needs to be greater accountability.

One policy option advocated by campaign groups includes increasing the litter fine to £1,000.63Clean Up Britain. (2020) Don’t Trash Our Future. Link Fines address the litter problem by increasing the cost of wrongful disposal. Despite this, fines remain difficult to enforce, and the perceived low probability of being caught means that fines can provide a weak stimulus to change littering behaviour. Some studies suggest that the deterrent effect of increasing an already stringent punishment creates only modest improvements in behavioural change.64Andreoni, J. (1991). ‘Reasonable Doubt and the Optimal Magnitude of Fines: Should the Penalty Fit the Crime?’, The RAND Journal of Economics, 22(3), pp.385–395. Link Too high a fine could even reduce enforcement, as some councils may be unwilling to impose a penalty they see as disproportionate, further compounding the enforcement problem. However, as explained below, there is scope for Government to triple the level of fines in the UK but not to the level of £1,000 which would be disproportionate.

Figure 1: Fly-tipping enforcement actions in England, 2012/13 to 2020/21.65Ibid

Policy Recommendations

- Triple the level of fines. At present, the default level of fines for a littering offence does not reflect the scale of the litter problem in the UK and is notably smaller compared to other ‘on the spot’ fines or criminal acts. Tripling the level of fines significantly increases the deterrent effect and personal cost of a litter offence.

Following the 2017 Litter Strategy, the Government increased fines for littering. The maximum ‘on-the-spot’ fine local authorities can issue for dropping litter almost doubled from £80 to £150. The minimum fine increased from £50 to £65, whilst the default fine increased from £75 to £100. This followed a consultation which found that 87% of respondents favoured an increase in litter fines. There is, however, a clear need for the Government to increase these fines again.

Compared to cleaner cities and countries, the current UK level of fines is modest. For instance, in the Canadian city of Calgary a litter fine ranges from C$500 to C$ 1,000 (£317 to £636).66The City of Calgary. Bylaws related to littering. Link In Singapore a litter offence results in a fine between $300 to $1,000 (£184 to £614)67Stanfort Academy. Singapore Laws. Link and in Venice, a popular European honeypot, a littering offence incurs a flat fine of €350 (£300).68https://www.comune.venezia.it/en/content/comportamenti-vietati The world’s cleanest cities and countries enjoy touting their environmental credentials abroad and is an alluring factor for tourists. Cities are frequently surveyed by various publications and cleanliness is a prominent feature. In 2009 London was named Europe’s the dirtiest city in a survey conducted by the Independent,69The Independent. (2009) London named dirtiest city. Link whereas Singapore was the world’s cleanest and greenest city in the 2021 Time Out Index.70Time Out. (2021) Singapore is named one of the best cities in the world – and the cleanest and greenest. Link If the UK is to change its global reputation for littering and cleanliness, the Government should take its lead from the cleanest countries and increase the level of litter fines.

In addition, the current level of fines is again modest compared to other ‘on-the-spot’ fines and does not reflect the scale of the UK’s litter problem. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government introduced legislation enabling police officers to issue ‘on-the-spot’ fines for violating restrictions. Fixed Penalty Notices ranged from £200 for failure to wear a mask to £10,000 for illegal raves and large gathering.71Joint Committee on Human Rights. (2021) The Government response to covid-19: fixed penalty notices. Link Whilst not a global pandemic, the UK’s litter problem has nonetheless been described an epidemic. Compared to offences in the Road Traffic Act, a driver without insurance is liable to a £300 fine, overloading or exceeding axle weight of a vehicle is fined between £100 to £300, and a driver using a using hand-held mobile phone is liable to a £200 fine.72Sentencing Council. Link. Moreover, the Government recently increased the maximum penalty for criminal damage to a memorial, removing the consideration of monetary value of the criminal altogether, and increased the maximum sentence up to 10 years imprisonment.73Ministry of Justice. (2022) Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 section 50: Criminal damage to memorials, Circular No.2022/02. Link

As previously noted, some evidence suggests that a drastic increase in the level of fines only leads to modest behavioural change and improvements. The fine does, however, have a deterrent effect, especially if accompanied by a new information campaign (see recommendation three). Whereas a drastic increase to £1,000 fines is disproportionate as proposed by various anti-littering campaign groups, on balance the current level of fines should triple for three reasons; first, to increase the deterrent effect of littering, secondly, resemble the level of fines in the world’s cleanest countries and cities, and finally, better reflect the scale of the litter problem as outlined throughout the report. As a result, the maximum ‘on-the-spot’ fine local authorities can issue for dropping litter should triple from £150 to £450; the minimum fine increase from £65 to £195, whilst the default fine increase from £100 to £300.

- Council League Table. A lack of enforcement generates a cultural understanding that littering, whilst frowned upon, is trivial – despite being a criminal offence. A league table, published as part of DEFRA’s ‘Litter Dashboard’, would rank local authorities on how actively they use their powers to tackle litter and littering behaviour. A league table would incentivise councils to develop local litter strategies, enable residents to hold councils to account, as well as instil a competitive spirit across regions and between metro-mayors.

A league table aspires to address the inability or lack of willingness to catch offenders by ranking local authorities on several metrics, such as the cleanliness of streets, how many litter fines are being issued, whether a local litter strategy is in place, and how actively local authorities are using their powers. The public would know the performance of their respective council authority. If a council performs badly, local public outcry will incentivise change.

A league table would rely on existing resources and fall within the remit of both the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA), as well as the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (DLUHC). Data input would be collated by DLUHC through existing challenges of communication between local and central government with DEFRA using this information to ascertain the extent of the litter problem and monitor improvements or the lack thereof, thereby enabling the department to direct resources to the worst areas. Moreover, by making use of the devolved structures, a performance measure would instil a healthy degree of competition between regions and metro-mayors. Just as Policy Exchange’s Modernising the UK report recommended the UK Government working closely with local authorities in the rollout of full-fibre broadband, a league table would facilitate a similar kind of dynamic. It would provide the relevant data and a more comprehensive picture of the UK’s litter problem for the UK Government to more appropriately direct resources and assist local areas. Metro-mayors would be able to compete for title of being the least littered region in the UK.

There is a risk, however, that fines become a revenue stream for local authorities, especially when outsourced to private enforcement companies. Potential revenue and profiteering should not be a motive for increased levels of enforcement. Dacorum Borough Council (DBC) in Hertfordshire recently approved the decision to enlist the help of a private enforcement company that “…could generate an annual revenue of £216,330”, providing “…a predicted annual revenue to DBC of £10,816.”74Dacorum Borough Council. (2022) PH-002-21 Littering and PSPO Enforcement. Link Defra’s 2019 guidance warns against this issue and states “…in no circumstance should enforcement be considered a means to raise revenue… private firms should be able to receive greater revenue or profits just from increasing. The volume of penalties”.75DEFRA. (2019) Effective enforcement Code of practice for litter and refuse’. Link Together with other instances, the evidence above suggests some local authorities contravene Defra’s guidance.76Manifesto to Club. (2022) ‘The Corruption of Punishment 2022.’ Link If the Government pursues an Enforcement League Table, elements of Defra’s guidance should become statute to ensure the policy is fit for purpose and serves to exclusively to reduce littering.

- A National Litter Awareness Course. Just like the National Speed Awareness Course that teaches the dangers of speeding and dangerous driving, a litter awareness course offers a chance to re-educate and change behaviour as an alternative to prosecution and fines. It would directly target the worst offenders.

The North Report in the late 1980s first proposed the idea of a driver’s re-education course as an alternative to prosecution. The report stated, “it must be in the public interest to rectify a fault rather than punish the transgressor… the retraining of traffic offenders may lead to an improvement in their driving, particularly if their training is angled toward their failings.”77NADIP. Driver Improvement Scheme – History and Background. Link The idea of rectifying driving behaviour rather than prosecuting gained traction in the 1990s and is now adopted by 41 of the 43 police forces in England and Wales. A recent evaluation suggests that participation in driving awareness courses has a direct causal effect on reducing reoffending.78Ipsos. (2018) Impact Evaluation of the National Speed Awareness Course. Link This demonstrates the policy purchase of re-educating those who commit an offence rather than putting added pressure on the judicial system to prosecute and convict the worst offenders.

Given the wealth of campaign literature, anti-littering charities are well positioned to provide this service. Moreover, the tripling of litter fines (as per the first recommendation) creates a greater incentive for individuals to opt for a cheaper litter awareness course. As a proxy, police forces across the UK charge between £80 to £120 for speed awareness courses as an alternative to a higher fine and points on a driver’s licence. If a litter awareness course bears a similar cost of £80 to £120, the worst litter offenders will choose the course provided by anti-littering charities rather than a more costly default fine of £300.

Education and Campaigns

While awareness and interest in environmental issues has never been stronger, there is a danger that too great a focus on activism and climate change distracts from individual responsibility and what a person can do to limit their impact in immediate environments. For instance, Nickie Aiken MP for Cities of London and Westminster, revealed that 120 tonnes of rubbish had been littered across her constituency following Extinction Rebellion protest in the capital in October 2019.79The Telegraph. (2021) Extinction Rebellion demo left 120 tons of rubbish on London’s streets, say council chief. Link Westminster City Council spent an extra £50,000 to clear up the rubbish. More recently, the activist campaign group, Just Stop Oil, issued an apology for leaving plastic rubbish near a protest site on a farm where 50 activists were arrested after preventing oil tankers entering a terminal nearby. Warwickshire farmer, Charles Goadby, took to twitter to express his grievance, highlighting the hypocrisy of the eco-activists.80Twitter. (2022) Charles Goadby ‘My message to @JustStop_Oil’. Link

Neglected in this flavour of activism, and perhaps environmentalism more broadly, is an emphasis on individual responsibility and what a person can do to limit their immediate environmental impact, such as properly disposing litter. In the National Curriculum there is a statutory requirement for Year 4 pupils to be taught to “recognise that environments can change and that this can sometimes pose danger to living things” and “the positive effect of nature reserves, ecologically planned parks, or garden ponds, and the negative effects of population and development, litter or deforestation”.81NAEE. (2015) The Environmental Curriculum, p.24 Link Whilst taught at a young age, an examination into youth culture and litter argued that littering behaviour is strongly entrenched in teenagers.82Keep Britain Tidy. (2007) ‘I’m just a teenage dirt bag, baby! Link This demonstrates the need for a more permanent campaign across all school years that targets not just children but also teenagers.

There are, however, some noteworthy examples of school initiatives that focus on littering. For example, Herefordshire Council in 2017 provided secondary schools with a litter resource pack, including lesson plans, ideas for school assemblies, and school litter picks.83Herefordshire Council. (2017) Secondary School Litter resource pack. Link County Durham has an anti-litter mascot, ‘Tidy Ted’, who visits primary schools and nurseries.84County Durhah. Tidy Ted. Link A range of organisations provide resources, such as the National Association for Environmental Education (NAEE),85National Association for Environmental Education (UK). Link The Countryside Charity’s school litter campaign guidance,86The Countryside Charity. Link as well as Keep Britain Tidy’s Eco-Schools initiative. The usage of available resources and materials is difficult to discern among schools across the country. Keep Britain Tidy runs a ‘Great Big School Clean’ and is now in its seventh year. In 2020, the campaign reached less than 182,000 school children, 0.02% of England’s 9 million pupils.87Keep Britain Tidy. (2021) Annual Report & Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2021. Link

Surveying the lesson plans and curriculums of Oak National Academy, an organisation backed by Government created in response to the educational impact of COVID lockdowns, highlights an opportunity within curriculums. Environmentalism is a cross-curriculum subject, such as ecosystems in biology, or changing landscapes in Geography. Citizenship education, however, aims to develop the knowledge, skills and understanding that pupils need to play a full part in society as active and responsible citizens.88Association for Citizenship Teaching. Link Within Oak National Academy’s lesson plans and curriculums, there is only a cursory mention of litter and its impacts. Littering and challenging littering behaviour, underpinned by an emphasis on individual responsibility, should form a greater part of teaching within schools across year groups with a specific focus in Citizenship curriculums. More consistent engagement with anti-littering charities in an educational setting has the potential to change and challenge littering behaviour amongst the litter prone age group.

There are also campaigns that go beyond educational settings. Campaigning is a popular method widely used by local authorities to generate local pride in public spaces and help individuals to become more invested in their local areas. Some local campaigns are successful. For example, the ‘Love Essex, Hate Litter’ campaign focuses on both education and enforcement to instil genuine behavioural change across the county. The 2016 campaign in Essex was entitled ‘Don’t toss it #BinIt’ with the slogan appearing across the county, ranging from bus shelters to local McDonalds restaurants. Its success led to an estimated overall reduction of 41% in fast food litter and its social media output shared across 2.4 million accounts.89LitterBin.co.uk Link In addition, various campaigns organisations enjoy national profiles leading on initiatives and driving the national conversation on littering, such as Keep Britain Tidy and Clean Up Britain.

Policy Recommendations

- New campaign to make littering socially unacceptable. This should be channelled through existing anti-littering groups, which are trusted by the public. Public funding, however, has declined with central Government withdrawing financial support as part of budget cuts in 2010. Such a campaign should target the youth and reinforce personal responsibility – if individuals wish to use and enjoy public spaces, respect for these environments should be paramount.

Campaigns have successfully garnered the backing of key businesses, widening the scope of the anti-littering message. As noted below, Mars Wrigley Confectionery possesses a 91% market share of the gum confectionery market and as a result a large majority (87%) of chewing gum packaging found to be littered is produced by one of its subsidiaries.90Keep Britain Tidy. (2020) Litter Composition Analysis. Link As such, the collaboration between DEFRA and Mars Wrigley Confectionery, on campaigns such as the Chewing Gum Task Force, are important.91DEFRA. (2021) Chewing Gum Task Force launched. Link It suggests that campaigns are an effective, lighter touch, method to engage business with the littering of their own products. Furthermore, Keep Britain Tidy’s recent national litter pick, the ‘Great British Spring Clean’, made 1.15 million miles of British outdoor spaces cleaner and greener.92Keep Britain Tidy. Great British Spring Clean. Link It gained the backing from businesses such as the Daily Mail, Mars Wrigley, Nestlé, Red Bull, KFC, McDonald’s, PepsiMAX, and Walkers. This suggests the propensity for business engagement through the campaign model.93Ibid

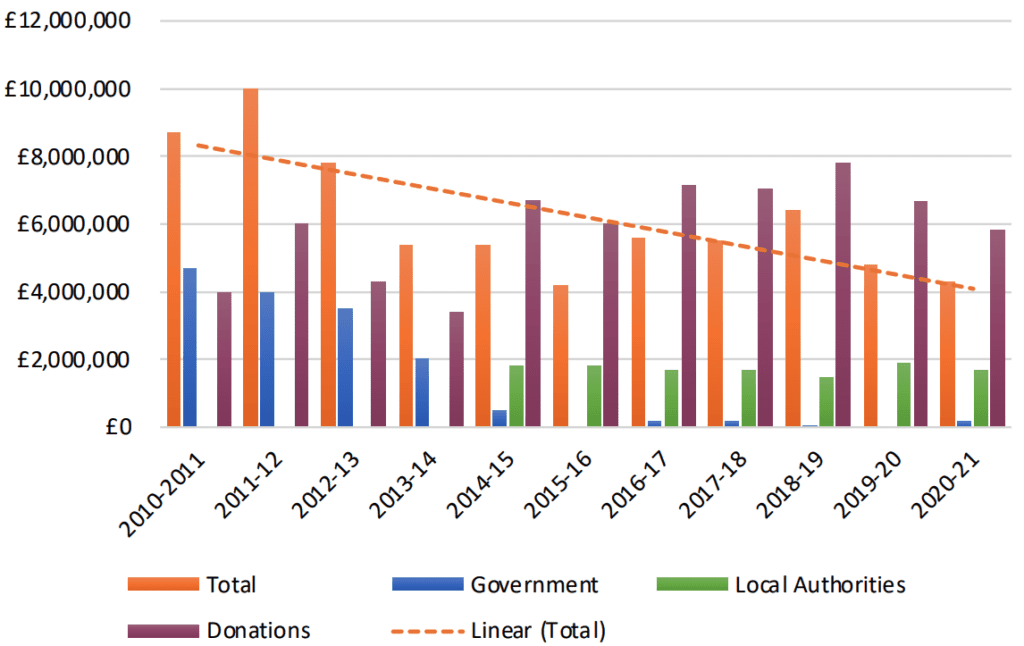

As suggested above, there is an opportunity for greater campaigning in educational settings that targets the most prolific littering age group. To achieve this, however, central Government funding should be reinstated for national campaign organisations, such as Keep Britain Tidy, with a greater emphasises on individual responsibility. Keep Britain Tidy received roughly £5 million from DEFRA in 2009 and £4.7m in 2010, representing approximately 50% of the charity’s income. Central Government funding was withdrawn from 2010 onwards as part of budget cuts. As figure 11 highlights, Keep Britain Tidy’s operational budget continues to be squeezed and is declining. The Government missed an opportunity to reinstate this funding with the launch of the UK Litter Strategy in 2017. Keep Britain Tidy has experienced a significant decline in income over the past 11 years despite playing an integral part in disseminating information and coordinating litter campaigns. The Government should reinstate this funding recognising the charity sector’s role in challenging and changing littering behaviour. In contrast, the Scottish Government in 2021 provided £9.2m in grant funding to Scotland’s equivalent charity, Keep Scotland Beautiful, representing 85% of the charity’s income.94Keep Scotland Beautiful. (2021) Annual report and financial statement. Link The Government cannot and should not tackle littering alone but rather work with campaign groups to bring about the societal change required to eradicate littering in the UK.

Figure 2: Keep Britain Tidy’s income as a charity.95Data was sourced from Keep Britain Tidy’s annual report and financial statements. Link

Binfrastructure

The 2017 UK Litter Strategy identified the issue of bin provision, so-called ‘binfrastructure’, as a key element to the problem of litter. The ease of binning rubbish properly remains an important issue due to either laziness, not enough bins, or bins overflowing. Research into littering behaviour has found that one in four litterers blame their behaviour on a lack, or perceived lack, of bins.96Keep Britain Tidy. (2004) I’m just a teenage dirt bag, baby! Link Further research has also found that littering rates increased the further away an individual is from a bin.97Clean Europe Network. (2015). Near Streets Impact Report. Link Innovative approaches to bins, however, have helped encourage user engagement. As outlined in the 2017 UK Litter Strategy, smart bins that, using sensors, inform the council when they are full can be easily introduced to create a more effective system of waste management in public places. The strategy highlighted the importance of bin placement, emphasising the role of bins in maintaining shared space, and discouraging littering through bin placement and design.

Projects such as Ballot Bins are an example of innovative binfrastructure policies.98Ballot Bin. Link This project by the Hubbub Foundation, trialled in Edinburgh and London, installed double slot ‘ballot’ bins which gave the public a chance to vote with their rubbish. The questions which people voted on made people engage with bins and can even make binning litter fun. This trial produced promising results: in Edinburgh 90% of business owners and workers in the area were aware of the new bins, and in London, the bins reduced littering by 8%, peaking at 18%, on the trialled street, collecting 29% of the street’s correctly disposed-of waste.

Moreover, binfrastructure which focuses on lowering the cost of proper disposal can have a significant impact on littering. Research by the Behavioural Insights Unit demonstrated that a strategy which prioritised the convenience and visibility of bins had ‘outsized impacts’ on reducing litter.99Behavioural Insight Teams. (2020) Using behavioural insights to combat PPE litter. Link Certainly, some experiments with innovative, low effort binfrastructure solutions have found that reducing the private ‘costs’ of proper disposal can reduce littering. A recent field experiment at eight beach resorts in the northeast coast of Italy found that ‘mobile ashtrays’ reduced litter by 10-12%, however social prompts did not dramatically increase uptake.100Economia Politica. (2021) ‘Smoke on the beach’ On the use of economic vs behavioural policies to reduce environmental pollution by cigarette littering. Link

Importantly, however, making bins more available should not be confused with carte blanche collection. In one case where councils provided a free clearing service for market traders, local businesses simply put their business waste out at the same time, so that it would be collected for free.101Keep Britain Tidy. (2018) Understanding and Tackling Fly-Tipping in London. Link Nor can more bins solve every litter problem. For example, one survey found cigarette butts within 5 metres of a bin, and roughly half of all smokers stating they would not walk ‘more than 10 paces’ away to properly dispose of their cigarette butt; only one third stated they would walk further that about half of smokers would not walk more than 10 paces to use a bin.102Tobacco Control. (2011) Whose butt is it? Tobacco industry research about smokers and cigarette butt waste. Link Given cigarette butts’ notable contribution to litter composition, better binfrastructure policies must also provide for smokers.

Policy Recommendations

- Embed the provision of bins and ashtray in strategic sites within design codes. The provision of bins is largely absent from designs codes, including the National Planning Framework. Mandating bins in design code enables a dialogue between local authorities and private developers ensuring better place making and local development, as well as balance the provision of bins between the private and public sector. It should also promote a more unified public realm design strategy where litter bins are discreetly incorporated into other elements of street furniture, such as bus stops, benches, and lampposts. Not only would this provide more opportunities for litter disposal but also encourage a cleaner, more streamlined visual landscape reducing litter and street clutter.

After the publication of the 2017 Litter Strategy, the Waste & Resources Action Programme charity (WRAP) produced guidance for local authorities on the design, number and location of public litter bins and other items of street furniture designed to capture litter.103WRAP. (2020) The Right Bin in the Right Place. Link The guidance was comprehension but only existed to inform local authorities. It did not go on to influence the Code of Practice on Litter and Refuse to include binfrastucture policies. Additionally, the provision of bins is absent from the National Planning Policy Framework. Together with the Code, elements of WRAP’s guidance should be embedded within design frameworks of public spaces. In doing so, responsibility for better binfrastucture would be extended to include private developers through the planning process, as well as cement the Government’s commitment to improving binfrastructure as a key element of the Litter Strategy. Developers, local authority planning officers and national planning policymakers will need to think strategically about the placement of bins. For instance, mandating bins at bus stops where people congregate for long periods of time waiting for buses in public spaces. Doing so would also prevent litter being deposited in buses thereby making both public transport and public spaces cleaner underpinned by a more unified public realm design. Discreetly incorporating bins into other elements of street furniture would therefore provide a more streamline and aesthetic visual landscape.

- Re-run the Binfrastructure Capital Grant Fund but allocated by formula. The placement and provision of bins and ashtrays is necessary and important; however, the last round of funding saw low participation by local authorities. Rather than local authorities bid for funding, allocation by formula is more time effective enabling local authorities to focus on delivery, with local authorities needing only to demonstrate proof of installation to draw down funds. In conjunction with the first recommendation, more funding provides an opportunity for local authorities and regions to be proactive and compete on the Council League Table.

In addition to the WRAP guidance following the Litter Strategy, the charity also administered Government funding for local authorities to improve the provision of bins. Local authorities were offered grants ranging from £10,000 to £25,000. Applicant local authorities were required to produce or have in place local litter and/or binfrastructure strategies. Uptake, however, was remarkably low. Of the 333 councils in England, only 44 authorities received grant funding.104WRAP. (2018) Litter Binfrastructure grant. Link In total, just under £1 million of funding was awarded with local authorities receiving on average £22,337.

Reasons for the lack of uptake are unclear, however, bidding for central Government funding can often be a costly and time consuming endeavour for local authorities, especially when the sums of money are small. Therefore, with a rebooted of the UK’s Litter Strategy, the Government should re-run the grant funding but administered by formula. It should take place one year after the implementation of a Council League Table to provide an opportunity for local authorities to compete and move up the league table. It will offer an incentive for councils to implement local litter and/or binfrastructure strategies that are currently absent and focus on delivery of better bins. Based on the previous grant funding, the below table outlines the approximate cost of re-running the scheme depending on take up rates. If there is an 80% take-up rate, re-running the Capital Grant Funding for better binfrastructure will only cost the Government approximately £5.9 million.

| Take up rate | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

| Cost | £0.74m | £1.47m | £2.21m | £2.95m | £3.68m | £4.42m | £5.16m | £5.90m | £6.63m | £7.37m |

| Littering in Fiji |

| Over the past 15 years, Fiji’s litter problem has risen to the top of the political agenda. Littering had become commonplace, impacting Fiji’s immense natural beauty – causing damage to not only fragile ecosystems but also potentially impacting its lucrative tourism industry. The first concrete measure taken to tackle the problem came in the form of the 2008 Litter Act. This Act laid out harsh penalties for littering, mirroring those in Singapore, and made clear distinctions between ‘litter’ and ‘dangerous litter’ – such as glass or corrosive chemicals and materials. Dangerous littering can result to up to one year in prison for an individual. Additionally, any corporate body who engages in such activity on two occasions can face a fine of up to $10,000. A key innovation in this Act was its creation of ‘litter prevention officers’ who are entitled to enforce the Act at any time, and they include any police officer, land transport officer, public health official or public officer. They can impose instant community service to clean up an area. This created greater accountability and broader surveillance for littering with more citizens able to legally enforce the Law. In addition, all public vehicles and spaces were required to provide adequate provisions for litter.

This Act was somewhat successful but in 2020 the Fijian Minister for the Environment, Mahendra Reddy, reaffirmed that litter was still the main contributor to environmental damage in Fiji and a major cause of flooding. He felt that not enough was being done to create a sustainable solution to the problem of litter so created a think tank named Litter Free Fiji. The think-tank aims to address the problem of litter from the supply-side emphasising the importance of recycling, reusing, and reducing in the waste management process. |

Two Schemes: Deposit Return and Extended Producer Responsibility

Several decades ago, Deposit Return Schemes were largely used as a method to collect glass bottles, such as the milkman delivering and collecting bottles to be re-use for customers. The shift to plastic, however, led to the demise of privately run Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) with cheaper single use plastic packaging alternatives.