Authors

Content

Foreword

By Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP

Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (2021-2022)

Twelve months ago, I announced to Parliament that a concerning new variant of Covid-19 had been detected overseas. The sequence B.1.1.529, better known now as Omicron, was probably already on our shores and would very likely go on to infect millions of people.

As had been the case throughout the pandemic, we faced a race between the vaccine and the virus. Within weeks, the total number of boosters delivered reached 35 million. On a single day in December, over 1 million Covid-19 jabs were administered.

Severe restrictions avoided, and thousands of lives saved. All due to vaccination and our pharmaceutical defences.

There is much we can learn from the past two years. For vaccination policy, the challenge is to create a sustainable framework both in the face of future public health emergencies, and the need to help build a healthier population.

Helping to build that population requires a long-term focus on prevention. This country had been at the cutting edge of health improvement in the past. But the pandemic shone a light on the critical issues we face today. We know that poor health, exacerbated by severe disparities across the country, is not just economically destructive, but socially unjust.

We must not shy away from this. Fortunately, we have the tools available to improve health outcomes and vaccination is amongst the most effective. We are now capable of vaccinating against more than a dozen preventable diseases across people’s lives. This not only enriches the lives of individuals, but our economy as a whole – as well as relieving pressure on public services.

The case for strengthening our national vaccination policy is therefore extremely strong and this report offers some credible and important ideas to make this a reality. This excellent report offers several notable pointers:

First, the development of better immunisation infrastructure at a national and local level. This will not only help to expand the offer of vaccination to communities– but provide the UK much needed resilience to tackle future health challenges.

Second, the use of digital technology and data. We must look at the huge advances of the pandemic, not just as a quirk of history, but the start of a new era of digital transformation, and a platform upon which to build. By enabling the responsible flow of data around the system in vaccination policy, we can better inform and refine our strategies to encourage uptake.

Third, it is clear we should be making better use of our wider workforce – including capable volunteers and medical and nursing students to support our seasonal rollouts. This needs to be planned with care to complement the expertise of our practice nurses, GPs and pharmacists.

The fragility of disease control means that I will sadly not be the last Health Secretary to stand at the Despatch Box and announce the spread of a concerning new disease. It is because we know this is inevitable, that we must do more now to strengthen our health infrastructure.

As a Conservative, I believe that we have a responsibility to preserve and replenish the health of the nation. We are in a strong position to do this and possess a historic global leadership position in vaccination. We must do all we can to keep it.

Next chapterEndorsements

“COVID-19 reminded us all of the vital role vaccination plays in protecting our health. With many new vaccines currently in development, this report offers a wealth of credible ideas to ensure the UK is well placed to deliver the vaccines of the future to those who need them. It includes practical measures to strengthen the important work of JCVI, support front-line immunisation teams and create new ways for people to be vaccinated at a time and place that suits them.”

Dr Richard Torbett, Chief Executive, The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry

“In a challenging time for health and social care services, the Covid-19 vaccine is one example of how building partnerships in local communities and listening to people’s concerns resulted in an efficient and successful roll-out of a health intervention. This important research builds on that model, suggesting the best way to improve take-up of key preventative vaccines is by giving more power to local providers working in partnership with pharmacies and communities. It also suggests making better use of the NHS app to support vaccination bookings and records, something we know makes people feel more empowered and in control of their own health. Vaccines are an essential part of preventative health, underpinning an effective national health system, and it’s important we don’t lose sight of maintaining and improving public trust and take-up through the strategies this research recommends.”

Louise Ansari, National Director, Healthwatch England

“As a former DPH, I warmly welcome this comprehensive and visionary report from Policy Exchange which builds on the lessons learnt from the long experience of implementing immunisation, recognises the challenges facing local authority public health teams, especially in terms of investment, but highlights their critical role in strengthening the resilience of the nation’s health protection system through their statutory role in boroughs working with a wide range of stakeholders to protect the health of their populations. The report’s progressive and practical recommendations should be considered carefully by policymakers not least because of their timeliness with WHO warning that measles is now an imminent global threat following the pandemic and currently, in England, where vaccination rates have dropped to their lowest in a decade. There is a pressing need to take urgent action to ensure English immunisation policies, systems and services can respond effectively, rapidly and flexibly to those challenges and the recommendations offer the possibility of making that happen from the practical steps to create a flexible wider public health workforce, timely, robust shared digital surveillance systems and data reporting and the strengthening and reform of JCVI and setting up of a National Immunisation Board. This important report is a must read and its recommendations if acted upon will implement the lessons from the pandemic and ensure that England has an immunisation system not just fit for today but fit for the future”

Professor Kate Ardern, Former Director of Public Health, Wigan Council; Former Lead Director for Health Protection, Greater Manchester Combined Authority & Honorary Professor of Public Health, Salford University

“This timely and thorough report from Policy Exchange acknowledges the important role public health teams across the country play in supporting vaccination efforts and profiles some of the innovative ways that local government has partnered with the NHS to drive uptake in recent years. We welcome the measures proposed which look to foster greater cooperation between providers at a local level, and think the proposal to establish ‘Vaccine Collaboratives’ is worth further consideration. We were particularly pleased to see our call for a Memorandum of Understanding and Framework Agreement between UKHSA and the LGA also advocated in this report to strengthen links between national and local decision-makers”.

Councillor David Fothergill, Chair, Local Government Association Community Wellbeing Board

“I welcome this report from Policy Exchange which recognises the vital contribution of pharmacy teams in supporting flu and COVID-19 vaccination programmes each year and in engaging local communities to reduce vaccine hesitancy. Driving vaccine uptake across the life course will require concerted effort across Government and the NHS. It is heartening therefore to see proposals which look to encourage the conditions for community pharmacy to do more, with proposals to commission pharmacy to deliver more adult vaccines, measures to boost the vaccination workforce and to improve information sharing between providers across primary care so that ‘opportunistic’ vaccination can be more easily achieved. We hope many of these practical proposals are taken forward.”

Thorrun Govind, English Pharmacy Board Chair, Royal Pharmaceutical Society

“We welcome this timely report which recognises the important – and growing – contribution that community pharmacy plays in delivering national vaccination programmes. We have long campaigned for community pharmacies to be the natural home for all vaccinations. From commissioning community pharmacy to administer more vaccinations, enabling pharmacy technicians to administer them and improving accessibility to patient records – Policy Exchange has produced a range of credible ideas here which ought to be taken forward”

Malcolm Harrison, Chief Executive of the Company Chemists’ Association

“The Royal Society for Public Health welcomes this new report from Policy Exchange which draws upon insights from own work on measures to promote vaccination uptake across the life course as well as the perspectives of a wide range of public health professionals. The result is a credible set of policy solutions which ought to be taken forward. In particular, we are pleased to see an emphasis on measures to tailor campaigns to meet the specific needs of communities (particularly those that are underserved) and to leverage opportunities to engage a new generation of public health professionals through immunisation activities.”

Dr Jyotsna Vohra, Director for Policy and Communications, Royal Society for Public Health

Next chapterExecutive Summary

“Will it make the boat go faster?” That was the challenge that a group of British rowers set themselves when they agreed a target to achieve an Olympic Gold in the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Each possible innovation would be tested through this prism. If it helped the boat go faster, it was kept. Anything which slowed progress was dispensed with.

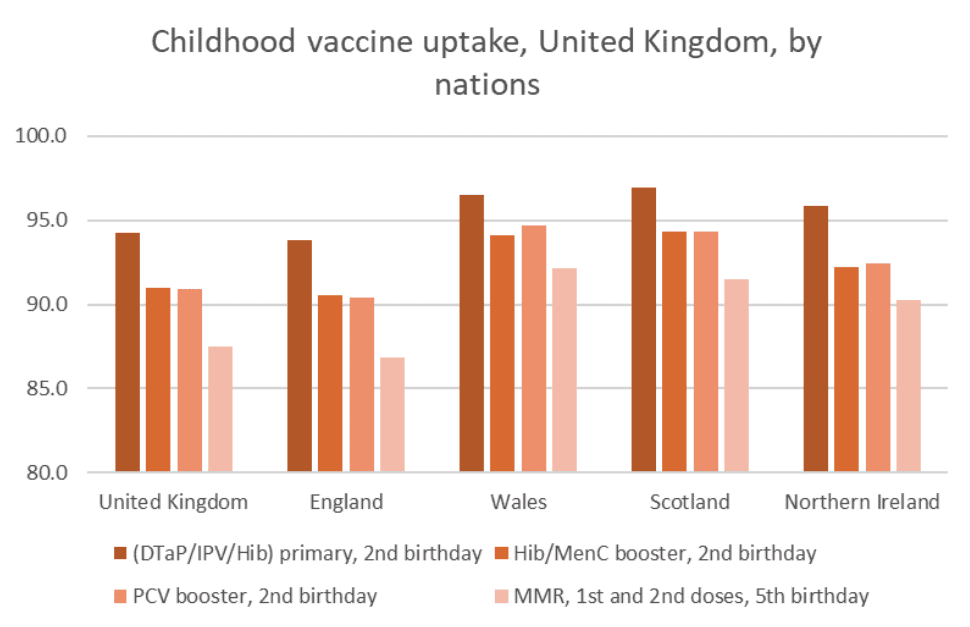

A similar approach is now required for immunisation policy in England. In the mid 1990s, the country was an international leader, boasting high uptake, effective delivery infrastructure and a strong pedigree in the identification, development, commercialisation and assessment of new vaccines. Yet coverage rates of the routine schedule which provides protection against fifteen vaccine-preventable infections, has been in decline. According to the latest figures from NHS England, no routine childhood vaccination met the 95% uptake target set by the World Health Organization. Our leadership position is under threat.1Emma Wilkinson, ‘All childhood vaccination uptake falls below 95% target in England’, Pulse, 29 September 2022 [link]

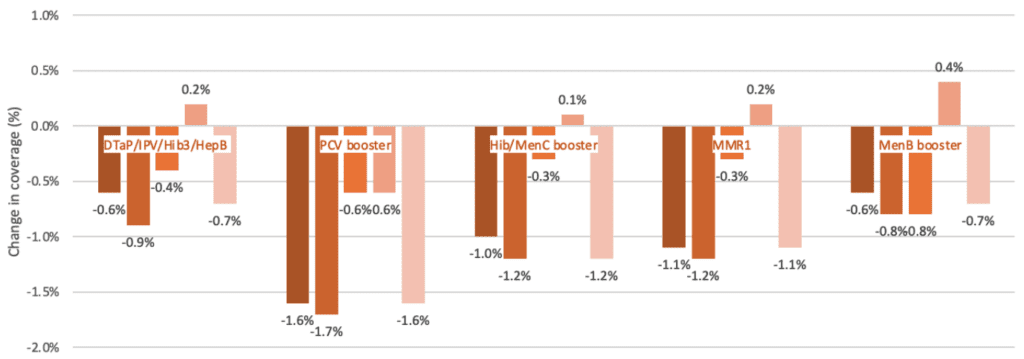

To reverse this trend, we must understand how we got here. Our research suggests that decline has been driven by several factors: some due to how the vaccine is delivered locally; others systemic, such as data reporting; and others circumstantial.

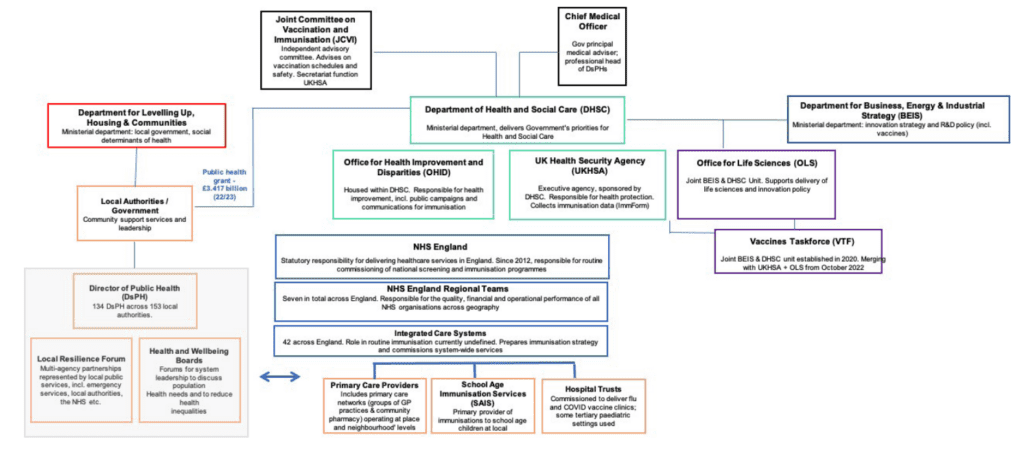

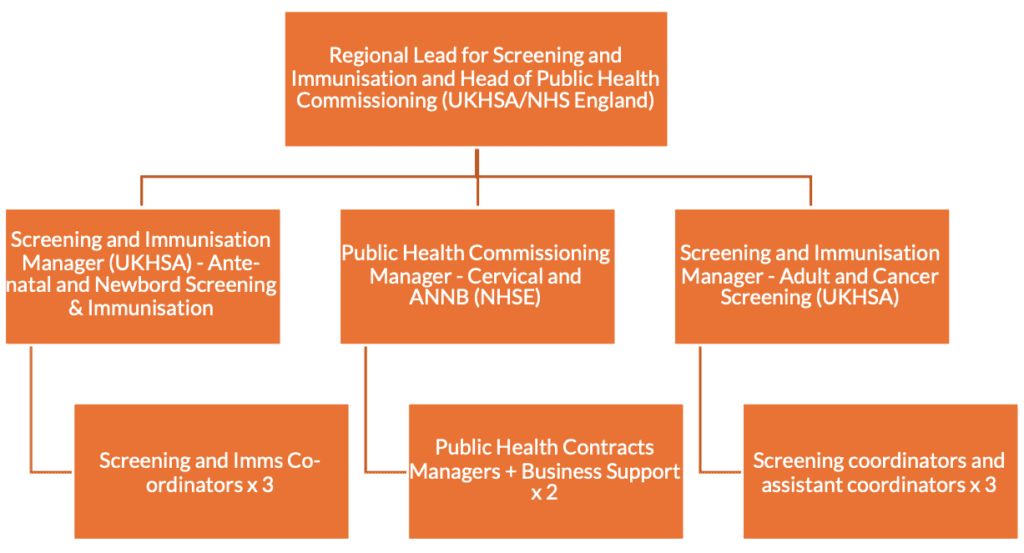

In chapter one we explore the policy context in detail. We have concluded that the governance and accountability arrangements for vaccination and immunisation are poorly understood and may themselves be contributory factors towards low uptake. Following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, responsibility for vaccination was moved from primary care trusts (which were abolished) and instead held within a tripartite national delivery framework between NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care, and Public Health England (whose responsibilities are now divided between UKHSA and OHID). Delivery is organised through a Local Operating Model. In the past decade, additional organisations have been introduced to the picture at a national level. Attempting to visualise interrelationships between these organisations as we have done in Fig. 1, page 30 is challenging.

In writing this paper we carefully evaluated the benefits that could derive from a streamlined structure. However, when set against the impact of disruption, we have concluded that it would be unwise to make major changes to the current tripartite arrangements. Vaccinations, as with other health protection initiatives, are complex and have multiple interfaces. Policymakers need to accept this. The focus should be on ensuring there is as much clarity as possible over decision making within the existing structure, rather than seeing reorganisation as the answer. We believe this is important to emphasise as a new Ministerial team joins DHSC, and NHS England moves towards a new operating model.

Clarifying responsibilities and communicating these externally would make a material difference. But more fundamentally it will need to be accompanied by an enduring political commitment to vaccines. Public health has been seen as a soft target for budget cuts when compared to the powerful interests within secondary care, where budgets have increased in real terms. By 2020/21, spending on the public health grant was 24% lower in real terms than it was during 2015/16. The Local Authority allocation for health protection work has been slightly better protected but was still 14% lower than five years earlier.2David Finch, Louise Marshall & Sabrina Bunbury, ‘Why greater investment in the public health grant should be a priority’, The Health Foundation, 5 October 2021 [link]

This misallocation of resource – away from prevention and towards medicalised healthcare – was unwise. Interventions to improve public health delivers phenomenal bang for buck: health protection interventions such as vaccines are calculated to deliver a £34 return for every £1 invested.3Rebecca Masters & Elspeth Anwar et al., ‘Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review’, Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, Vol. 71, No. 8 (2017), 827-834 [link]

Health protection is an economic and a moral imperative. But it is also an area where the UK has pedigree, having been a world-leader in vaccine development, procurement, and delivery. The country’s rich history in discovery commenced with the smallpox vaccine, first tested by Edward Jenner in his Gloucestershire surgery, and culminated most recently in a licenced vaccine for COVID-19 based on technology designed by a team led by Dame Sarah Gilbert at the University of Oxford. Two world-changing public health discoveries – made 225 years apart, within 60 miles of each other.

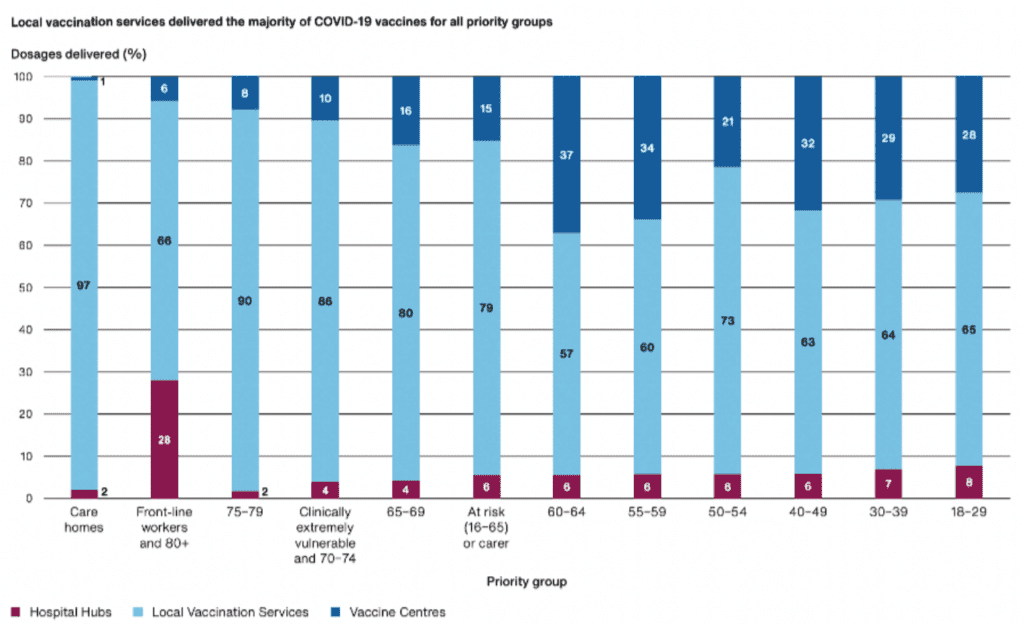

Elements of the UK’s approach to the COVID-19 vaccine rollout were ‘world beating’, but many comparator countries have since outperformed the UK in uptake. The Vaccines Taskforce – heralded for its agility and overall effectiveness, is to become a joint DHSC and BEIS unit, meaning that competing priorities and processes may encumber its workings.4Sarah Newey, ‘Dame Kate Bingham: ‘Downing Street was indifferent about vaccines’, Daily Telegraph, 10 October 2022 [link] Now is the moment to take stock – to both ensure that immunisation targets are reached, and to ensure the UK is the best place to test and launch the next generation of vaccines.5For a useful, recent review of which considers the learnings from COVID-19 for routine programmes, see Kate Causey & Jonathan F. Mosser, ‘Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic to strengthen routine immunization systems’, PLOS Medicine, Vol. 19, No. 2 (2022), 1-18 [link] Whilst there has been a rhetorical rebalancing over the past two years towards the value of vaccination, coverage reports show that many of the routine immunisation programmes are experiencing slow catch up. Regression modelling and analysis undertaken for this report sets out the specific impact for measles and shingles – and are outlined in Chapter Two which considers the impact of the pandemic on immunisation.

In Chapter Three, we set out a vision for a new vaccination policy for England. Our vision is for an integrated delivery model with components at every level: national, system, place and across neighbourhoods. We are advocating in favour of greater autonomy for local teams to design campaigns in their patch, bringing together different assets locally but supported by a strengthened national data architecture and proportionate programme oversight.

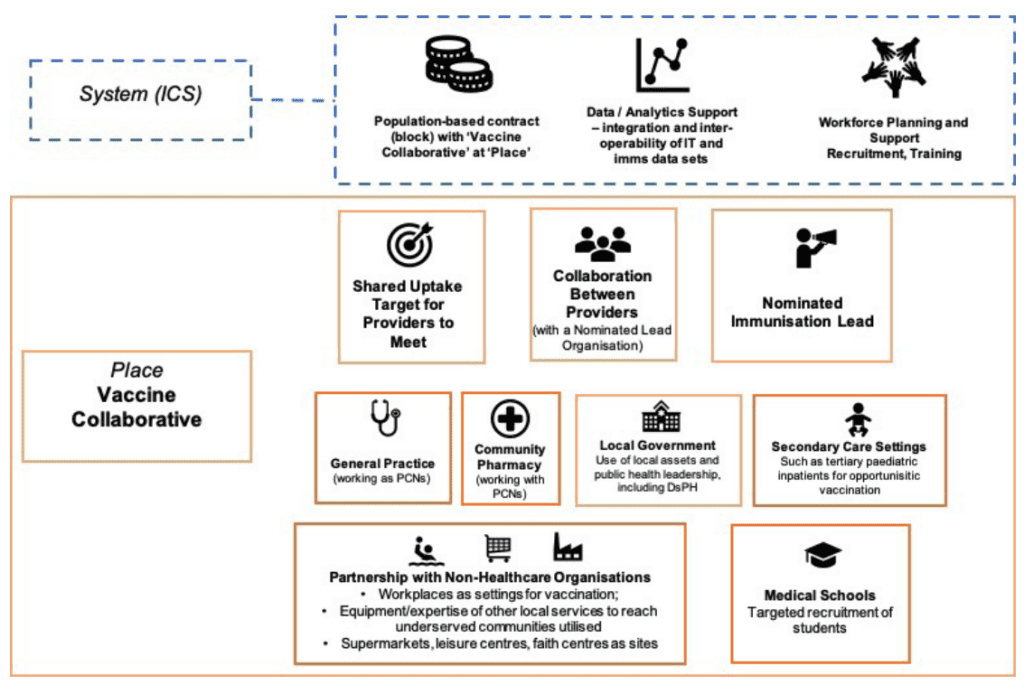

We know that being able to offer vaccination opportunistically is valuable, provided that data can be made available in the right places. So too is the trusted relationship between healthcare professional and patient in addressing legitimate doubts and wider hesitancy. Vaccinations – particularly those for children and of school age– should continue to be delivered within primary care or by School Aged Immunisation Services where the expertise and wraparound care of practice nurses, Immunisations Nurses, school nurses and GPs is a valuable asset. We want to see most resources tethered to that part of the system; but with a willingness to experiment with payment and provider models to allow community pharmacy to collaborate with colleagues in General Practice on a greater scale that we have seen in the past for adult programmes. The new Vaccination Collaboratives proposed in this report would allow deployment to be organised in a new way – shifting the accountability (and budget) onto local providers. A group of providers would be trusted to maximise their local assets to reach the highest possible coverage, with a particular emphasis on underserved groups. The tactics required to reach that target would be up for the local area to determine. In most instances, this could mean more of a role for local government, with the Directors of Public Health well placed to provide a leadership role. In others, we might see hospitals lean into their anchor institution role and become hubs for vaccination – such as those at high risk of being infected with influenza whose care may predominantly be in secondary care settings and where a dedicated clinic may be economical. We propose that these changes are piloted in three ICSs before wider national rollout.

This integrated model of delivery should become the default standard for rollouts, even in areas which do not enter into Vaccine Collaboratives. A single target could be introduced at neighbourhood levels to incentivise collaboration to reach the remaining 10-20% who are unvaccinated. Significantly, Policy Exchange believes there would be coherence to separate the planning of immunisations from screening services – currently delivered through a joint leadership team as part of Section 7A. Both would benefit from independent leadership and focus. Further details are outlined in Chapter Three.

Something we have heard clearly throughout this research is the strain on the healthcare workforce. There is a need to strengthen health protection capabilities across primary and community care more generally, but the current challenges necessitate tough choices. Having carefully considered the evidence, our view is that responsibility for adult vaccinations – particularly those of higher-volume, such as influenza and COVID-19, nurses, GPs and pharmacists should perform leadership and supervisory roles, with jabs delivered by a more heterogenous workforce. We recommend that the 35-40,000 medical students, 90,000 nursing students and 12,000 pharmacy students currently enrolled at universities in England are asked to volunteer to administer jabs for these two vaccines, being deployed each year to GP surgeries and community pharmacy during seasonal rollout campaigns, where they would support pharmacists, nurses and nursing assistants. These roles should be formalised.

We would expect a portion of the service to be seven-day and with extended hours enabled. This would be optimally planned at place level; with a minimum of one centre open per ICS footprint over weekends, resourced by the existing primary care community and the workforce groups mentioned above. The travel distances required for the public should be compensated by a well-resourced facility and smooth user experience.

The integrated immunisation delivery model should commence with an improved offer for the service user. This should not mean a wholesale change. Vaccines – especially in infants and children – are wrapped up in cultural significance. Mucking around with where they are delivered and not recognising the expertise that the nursing profession in particular brings to this activity will cause confusion for parents and families and may lead to lower uptake. But that should not mean we should not try to make routine immunisations more accessible. The national booking service established for COVID-19 sets the expectation. Coupled with the existing approaches we believe this should allow for a high level of user experience, irrespective of background. Nearly 90% of the British population now owns a smartphone. Through the NHS App, citizens should be able to view their vaccination status across the routine schedule, upcoming appointments, and date of dose expiry. This is commonplace in other countries.

This will require changes from the public, who must become more engaged in their own health. Elements to expand health literacy can be driven through initiatives coordinated by the NHS and UK Government, such as encouraging further sign-up to a vaccination research registry (modelled on the successful COVID-19 Registry) or by adding functions to the NHS App. A nationwide press and media campaign may also be required – especially for future vaccines which may suffer from the ‘ripple effects’ of the pandemic, including vaccination fatigue or renewed challenges with vaccine confidence.

Beyond the organisations with statutory responsibility, there is a key role to be played by the VCSE sector and independent advocacy groups. No single organisation currently ‘owns’ the immunisation agenda, and vaccines can struggle for clarity of voice, particularly compared to well-mobilised patient advocates in cancer, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases. Much like the prevention lobby, the pro-vaccine lobby is underpowered, with a dual mission of countering misinformation alongside conventional advocacy work to address legitimate hesitancy and reach underserved groups. A positive outcome of the pandemic should be the creation of a clearer standard bearer, independent of government, to champion immunisation across the life course.

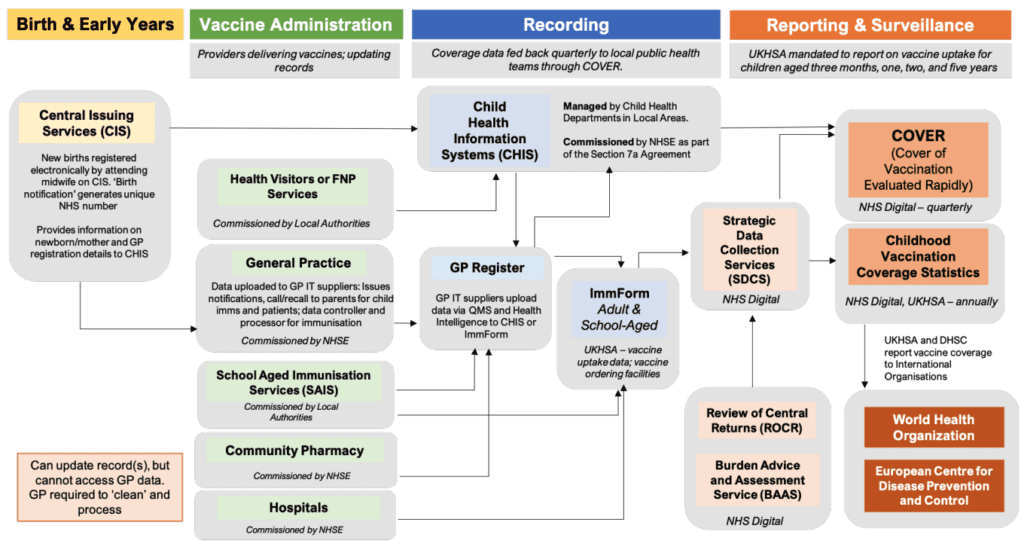

Effective data is the high-impact enabler of this new system. The aim should be for immunisation data to be accurate and seamlessly sharable across settings. In primary care, we need to move to a point where data is reliable and freely shared across pharmacy and general practice. This would be a transformation from the status quo. GPs have been wary of sharing patient data, often due to legitimate concerns.

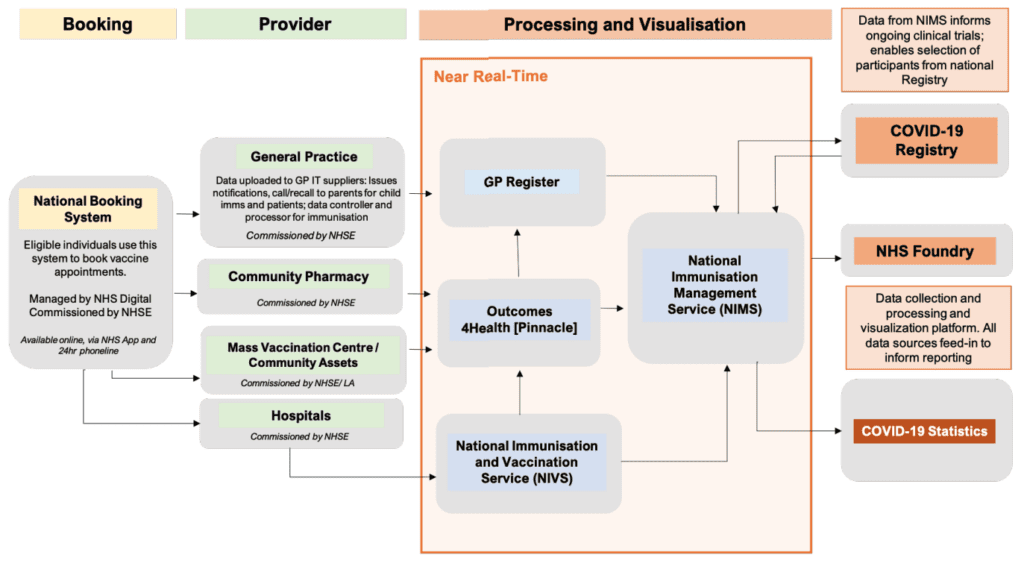

The impasse on data sharing must be broken. Data can drive uptake itself, through planning deployment in a way as to maximise efficiency and reduce health disparities. Improved data quality will free up precious GP capacity, with too much time spent assessing national releases, affecting the quality of ‘call and recall.’ For secondary-use cases, data can provide an accurate helicopter assessment on vaccination performance across programmes, enabling appropriate and proportionate interventions to be made as a result. There is much to mimic from the approach to data recording and transparency during COVID-19 whilst realising that the unique circumstances during the pandemic which meant that good practice around co-design was sacrificed for speed. The Federated Data Platform creates an opportunity to build wide stakeholder support.

There is much to be excited about in vaccines. The pharmaceutical industry has developed a strong pipeline – in areas from Tuberculosis (which has not had a new vaccine in 100 years) to Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).6‘Antibody jab approved for common winter virus RSV’, BBC News, 10 November 2022 [link] Whilst a lively discussion takes place regarding the wider prevention agenda, and a political focus on limiting the growth in the NHS budget to sustainable levels, this is an optimal moment to refresh current approaches to horizon scanning, modelling and health technology assessment. This should be accompanied by proportionate reforms to the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) to strengthen the transparency of its decision making. On the other side of the equation, manufacturers should engage in more active and early dialogue with governments and assessment bodies – echoing the ‘demand signalling’ mechanisms which have become commonplace in medicines. Outbreaks of monkeypox and re-emergence of polio in 2022 demonstrate that there can be no place for complacency.

This report makes 15 recommendations. Six are designated as critical recommendations which should be implemented immediately.

We are confident that, if implemented, this set of proposals would provide a strong basis for future vaccination policy. This will not only pave the way for new discoveries, following in the footsteps of Gilbert and Jenner. In some areas it will require a bold leap forward by policymakers, taking a calculated risk to get England’s coverage rates back into the gold medal position. But if these ideas make the boat go faster, what are we waiting for?

Next chapterOur Proposals in Brief

Six critical reccomendations – which we believe should be taken forward at the earliest opportunity – are highlighted in light orange

| Recommendation | Responsible Organisation(s) | Delivery Timescale | Implementation |

| National Leadership | |||

| 1.Enhanced Ministerial oversight through a new National Immunisation Board; clarify organisational remit and leadership roles for bodies responsible for health protection (incl. vaccination) (p .62) | No 10, DLUHC, DHSC, UKHSA, OHID, NHSE | By 2023 | The National Immunisation Board should meet for the first time in Q1 of 2023. Publish a National Vaccines Strategy by end of 2023. Where appropriate, the Board should meet, aligning with relevant groups in the devolved administrations such as the newly established Vaccination Delivery Board in Wales. |

| 2. Establish a National Immunisation Service (NIS) in England (p. 65) | NHS England, NHS SBS, NIHR, DHSC, DCMS | By 2024 | Define the scope and focus of NIS; establish a communications cell (aligned to Recommendation 13); enhance R&D capabilities (aligned to Recommendation 12). |

| 3. Separate immunisation from screening with distinct leadership and focus (evolutions to planning of Section 7A) (p. 67) | DHSC, NHSE, Local Government, SITs | By Autumn 2023 | Announce changes & issue advice by early 2023; implement changes by flu season in 2023, supported by the development of the NIS. |

| 4.Establish Vaccine Collaboratives in 3x pilot areas (p. 70) | NHS England, UKHSA, OHID, Local Government (incl. DsPHs), VCSE sector | By 2025 | Issue guidance and commissioning intention by 2023/24 with initial expressions of interest before assessment. First Vaccine Collaboratives to launch in 2024/25.

Requires amendments to GMS Statement of Financial Entitlements and the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework to allow for capitated budget with automatic clawback mechanism. |

| 5. DHSC and DLUHC encourage ‘stocktakes’ from Health Protection Boards to understand localised under provision and inform best practice (p. 75) | DHSC, DLUHC, Local Government, NHS England, UKHSA | By 2024 | Health Protection Boards (chaired by the local Director of Public Health) should conduct a ‘stocktake’ of local vaccination efforts to inform National Vaccines Strategy by Autumn 2023. |

| 6. Delegate Immunisation delivery to ICBs to enable increase in ‘evergreen’ offers (p. 76) | DHSC, NHSE, ICSs, Local Government | By 2024 | Additional support for specialist clinics (such as for those with learning disabilities) where provision at greater scale is an advantage. |

| Workforce | |||

| 7. Make the health protection workforce a key plank of a longer-term workforce strategy (p. 81)

|

DHSC, NHS England, HEE, VCSE | 2023-2028 | Enable nursing, medical and pharmacy students to opt-in to deliver seasonal vaccination (p. 93); NHS England to formalise roles and introduce contracts, reimbursement arrangements and medical indemnity. Create routes for experienced GPs, nurses and pharmacists to re-enter the workforce, undertaking immunisation activities as a protected activity. |

| 8. Establish Neighbourhood Immunisation Coordinators (p. 81) | NHS England, Local Government | By 2024 | Conceived as part of the Integrated Neighbourhood Teams proposed by the Fuller Review

|

| 9. Adapt the National Protocol and National Patient Group Direction (PGD) mechanisms to maximise the vaccination workforce, where it can be done so safely (p. 81) | NHS England, Local Government, VCSE

|

By 2024

|

Clarify indemnity for non-clinical workforce; maintain national protocols, such as Regulation 2 of the NHS Regulations 2013; amend The Human Medicines Regulations 2012 to enable pharmacy technicians to administer vaccines under a PGD |

| Data | |||

| 10. Create a comprehensive immunisation information system (IIS) to modernise immunisation data collection and analysis (p. 86) | DHSC, NHS EngIand, UKHSA, MHRA, NIHR

|

2023-2028 | Integrate UKHSA surveillance systems as well as databases held by the MHRA and NIHR. A centrally-commissioned communication capability should also be introduced. Its specification should cover invitation, booking and preparation processes. This could be modelled on the current Covid-19 & Flu National Booking System to enable lead organisation in a ‘Vaccine Collaboratives’ to reach patients via the NHS App, SMS, email or phone. |

| 11. Enable both care provider and patient access to health records (p. 93) | DHSC, NHSE | 2023-2025 | Introduce joint controllership of patient data between GP practices and NHS England; add data breaches to Clinical Negligence Scheme for General Practice (CNSGP); enable community pharmacy (as a priority) to access patient records to support immunisation |

| Engaging Citizens | |||

| 12. Additional functionality within NHS App, incorporating the ‘digital red book’ and an NHS Research Registry (p. 103) | DHSC, NHSE, NIHR | By 2024 | Improvements to booking function incorporated as part of enhancements to NHS App; development of a comprehensive Vaccine Research Registry to drive user and life sciences sector engagement (p. 125) |

| 13. Development of a permanent comms cell in the NIS to tackle vaccine disinformation (p. 95) | DHSC, NHSE, DCMS | By 2024 | Model on Rapid Response Unit introduced by Cabinet Office during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 14. Establish an umbrella Life Course Immunisation advocacy group (p. 101) | VCSE | By 2024 | Establishment of new charitable organisation, drawing upon expertise and talents across VCSE sector. |

| Assessment and regulations | |||

| 15. Evolve the workings and processes of the JCVI (p. 105) | DHSC, UKHSA, JCVI | 2022-2025 | Establish a dedicated ‘Horizon Scanning Sub-Committee’; Update the JCVI Code of Practice. |

Next chapter

Policy Recommendations

National Leadership

- The Government should set out plans to clarify the national governance structures for immunisation. Vaccines policy in England should have clear ministerial oversight (with a single Minister covering all elements of health protection). Whilst improved coordination between bodies is essential, we do not recommend organisational reform. New organisations, including UKHSA and OHID require time to ‘settle’ and for responsibilities to be clarified.

- The Vaccines Minister should establish and chair a new National Immunisation Board – emulating the National Genomics Board. The remit of the board would be England-wide, complementing similar arrangements being established in Wales. Membership would include the tripartite, alongside representatives from provider organisations responsible for vaccine deployment (including local government and/or The Association of Directors of Public Health. External experts would be invited on an ad-hoc basis. The objective would be to create a platform for the Minister to scrutinise progress and to hold programmes to account, not to duplicate the role and function of the JCVI in giving independent advice nor existing forums for dialogue with manufacturers. The Board would meet (at least) once every six months.

- UKHSA should hire a Commercial Director to support ongoing work of the VTF and should focus future investment to enhance surveillance capabilities.

- Over time we would expect to see a consolidation of the role of the NHS England Regions, a redeployment of resource to ICSs and more shared policy work across NHS England and DHSC. This should be gradual rather than immediate given the importance of the catch-up programme and the detrimental short-term impacts that a restructure may create.

- DHSC should publish an overarching Vaccines Strategy. This should be refreshed every five years henceforth, taking a ‘life course’ approach, fulfilling a commitment set out in the 2020 Prevention Green Paper.7‘Closed consultation – Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s’, Gov.uk, 22 July 2019 [link] The strategy should look to ensure that the most recent NICE guideline on improving vaccine uptake is adopted, universally.8Vaccine uptake in the general population, NICE guideline [NG218], 17 May 2022 [link] More broadly, our view is that the strategy should assume that responsibility for administration and deployment of most vaccines will remain in primary care and be led by general practice. There are two exceptions. A) The school-age immunisation schedule should continue to be delivered by SAIS providers in schools. B) For adult vaccinations we see an enhanced role for community pharmacy and the greater use of a ‘surge’ workforce capacity, with a formalised role for medical, nursing and pharmacy students in seasonal rollouts.

Delivery Models

- NHS England should establish a National Immunisation Service (NIS). NHSE should clarify at the earliest opportunity that the NIS would not represent a national delivery model for vaccines, but would represent a set of supportive services for ICSs, primary care providers and public health teams. All vaccinations across the life course should be incorporated within the work of the NIS (including COVID-19 and flu).9‘COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy for 2022 published’, Welsh Government, 24 February 2022 [link] Moreover, it should proceed on the basis of improved alignment between approaches taken across the devolved nations – in the future model, service users should be able to receive a first jab in England and a booster in Scotland, minimising fragmentation in service provision. This should be enabled despite devolved administrations developing their own delivery models (such as the ‘hub model’ being developed in Scotland). We believe it should focus upon strengthening the following elements at a national level:

- R&D capabilities, including working with NIHR to enhance patient registries and to support clinical research;

- Ensuring a consistent national voice on misinformation (with a dedicated communications cell working w/ DCMS and DHSC;

- Creating a more effective ‘pull system’ for providers and strengthening role of NHS Shared Business Services to cope with ‘surge’ demand and to support providers beyond secondary care;

- Simplifying mutual aid between providers.

We also believe the NIS can lock-in some of the positive consumer-focused initiatives developed during the pandemic. This should involve the creation of a national booking service across vaccination programmes – with the option to book, change, or cancel appointments at a range of settings (where applicable). The booking service for COVID-19 vaccines sets the minimum expectation.

- As part of the creation of a NIS, NHS England should re-examine how Section 7a responsibilities (commonly known as public health commissioning) are planned. Immunisation and screening programmes are currently combined under a single team within NHS England with leadership from a National Director. Our contention is that screening and immunisation are distinct from each other, and it will increasingly be necessary for them to be planned for separately, given both programmes grow in number and complexity. In reviewing the operationalisation of S7a, the Government and NHS England should review current gaps in provision – or where vaccination is recommended but isn’t covered by routine S7a programmes. An example would include a patient who has had a bone marrow transplant and require a full course of vaccinations. Community pharmacy should be commissioned to deliver all adult vaccinations through National Enhanced Services.

- NHS England should announce a pilot for the development of ‘Vaccination Collaboratives.’ The 2021/22 GP contract saw vaccination and immunisation become an essential service with a standardised item of service (IoS) fee set at £10.06 for most vaccines. A graded points system was introduced to incentivise surgeries to reach 95% coverage. These were the most significant reforms to immunisation payments in three decades, and need time to bed-in nationally. However, the broader shift within the system to new, non-activity payment methods should create opportunities for a collaborative approach on vaccination too. In the pilot area, the IoS payment would be replaced by a population-based contract to a ‘Vaccination Collaborative’ – bringing together community pharmacy, general practice, local government, the VCSE sector and other providers to collectively meet the needs of their citizens. We foresee a key role for local Directors of Public Health and the involvement of local authority commissioned health outreach and inclusion teams. This approach could take the form of a pilot amongst three ICSs (each representing a rural, semi-urban and urban demography). Amendments may be required to the GMS Statement of Financial Entitlements, and the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework to allow for the novel payment mechanism. The principal objective would be to pool resources most efficiently, free up clinical time for other activity and improve uptake amongst underserved populations.

- DHSC and DLUHC should encourage Health Protection Boards (chaired by the Director of Public Health) to undertake local ‘stocktakes’ of vaccination uptake, to profile disparities and to analyse efforts required to better meet the needs of underserved communities by Autumn 2023. NHS England and OHID should collate and publish combined best practice guidance for vaccination services. Whilst there is no shortage of best practice, this is not currently compiled and published nationally. This exercise should draw upon evidence from CQC, the most recent NICE guideline, system level coverage reports as well as integrating the work of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s Vaccine Confidence Project. Most significantly it should highlight the processes and steps taken to achieve the outcome, emphasising repeatability.

- The commissioning of immunisation should be delegated to integrated care boards (ICBs) over time to strengthen whole-system approaches to health protection. The new ICS structures should play a role in enabling an ‘evergreen’ immunisation offer at a local level, both commissioning and providing oversight to traditional providers and Vaccine Collaboratives where they are established. Expertise for vaccination currently sat within the NHS England Regions is valuable and should be gradually redeployed to ICSs as NHS England Regions take on a more strategic role. Within this:

- ICBs should commission ‘evergreen’ immunisation offers to support those from traditional providers, including mobile and pop-up vaccination units (such as vaccination buses) to target outreach of underserved groups, such as the homeless, in popular locations, such as supermarket car parks and town centres.

- Additional support should be provided to ensure improved provision of ‘specialist’ vaccination clinics to improve uptake amongst those with learning disabilities and autism. There are roughly 30,000 people with learning disabilities within each of the 42 ICS footprints. A specialist clinic would typically involve relatively minor adaptations to an existing site to make it a calmer environment, with longer, staggered appointments and a higher proportion of staff with relevant expertise, such as learning disability nurses.

- Neighbourhood immunisation coordinators should be created [see recommendation 11]

- ICSs should consider the possible benefits of non-traditional providers boosting their immunisation offers. Children’s hospitals and units with emergency and tertiary paediatrics have potential to deliver childhood immunisations, although this must be carefully modelled to determine whether the return is justified given the additional requirements, including enabling data sharing from Child Health Information Services (CHISs). Examples which could prove beneficial across the adult programme would include specialist HIV clinics.

Workforce

- The immunisation workforce should be rethought as part of the new fifteen-year workforce strategy being developed by the Government. Most vaccines are delivered by practice nurses, school nurses, immunisations nurses, community pharmacists and GPs. This workforce – operating primarily across primary and community care should be strengthened and expanded, recognising the benefits to having a workforce with specific expertise in immunisation. In addition to the role played by Health Education England, there will be a critical role for the Local Government Association and The Association of Directors of Public Health in informing strategic workforce planning for health protection. We see significant opportunities for training and workforce planning to be streamlined and strengthened as a consequence of the merger of NHS England and Health Education England.

- Efforts to leverage the attractiveness of vaccination activity should encourage the development of dedicated schemes at system level, to enable recent retiree healthcare professionals, including nurses, GPs and pharmacists to undertake vaccination work as a specific, and protected activity.

- All medical, nursing and pharmacy students should be able to opt in and trained to deliver immunisations – except where there is a strong clinical rationale for not doing so (or adequate supervision cannot be assured). A new minimum expectation will encourage students to support with vaccine deployments for at least two days over the course of their studies. This approach should be formalised, with contracting and reimbursement for sessions delivered introduced.

- A greater role for volunteers, enlisted to work within a dedicated local footprint – either as part of a Vaccine Collaborative or other primary care provider during surge periods (particularly the seasonal rollouts of influenza and COVID-19 vaccines). This would seek to take advantage of the existing trained volunteer workforce (St John Ambulance trained 26,500 volunteers during the pandemic.) This approach should explicitly draw on recently trained volunteers – some of whom developed the capability to train members of the public to vaccinate.

- The creation of new pathways for non-clinical staff and volunteers to develop skills and experience – so that some can become specialist immunisers with further training. Encouraging uptake of Royal Society for Public Health qualifications should be encouraged by systems, whilst NHS England should clarify medical indemnity for the non-clinical workforce.

- Neighbourhood Immunisation Coordinators should be established as part of the ‘Integrated Neighbourhood Teams’ proposed by the Fuller Review. These would be named individuals who can respond to queries and provide a local focal point. The role would typically be filled by a clinician or public health expert although that is not a requirement. It would be the equivalent of 0.25 whole time equivalent role, paid at AfC band 8a. Concurrent with most the recent NICE guideline, this could overlap with the nominated person responsible for identifying housebound immunisers.

- Adapt the National Protocol and National Patient Group Direction (PGD) mechanisms to maximise the vaccination workforce, where it can be done so safely. This would include:

- Adding Pharmacy Technicians to those able deliver vaccines through a Patient Group Directive (PGD) with an amendment to The Human Medicines Regulations 2012. It would be important however to ensure that any changes are accompanied by strengthened quality assurance measures.

- Proportionate amendments to the National Protocol, such as adapting Regulation 2 of the NHS (Performers Lists) Regulations 2013 (which removed the requirement for those administering COVID vaccine to be registered on the medical performers list) should be maintained where it is clinically appropriate to do so.

Data

- DHSC and NHS England should create a comprehensive immunisation information system (IIS) to modernise immunisation data collection and analysis, drawing upon international best practice, so that everyone works from a ‘single version of the truth.’ (CRITICAL RECOMMENDATION). This should involve the following changes:

- Creation of a single national platform. Following the successes of NHS Foundry as part of COVID-19 vaccine deployment, the NHS is currently tendering for a Federated Data Platform (FDP), in a multi-year deal worth up to £360m. Vaccination and immunisation is included within five indicative use cases. We believe that the FDP should – at a minimum – offer the ability to integrate with existing GP patient records, to allow for population cohorts and vaccine coverage reporting. Over time this ‘single version of the truth’ should be used (with varying levels of access) across the health and care system. Coverage reports should be broken down by neighbourhood, place, and system.

- Within an ICS level, each system should appoint data managers to oversee data quality within the FDP.

- A centrally commissioned communication capability should be introduced alongside this. Modelled upon the current Covid-19 and Influenza National Booking System, the aim is to enable providers (and eventually, ‘Vaccine Collaboratives’) to choose software from a nationally specified framework which would cover invitation, booking and preparation processes. The framework should specify that cover a variety of channels, including NHS App, SMS, email and telephone.

- NHS England should enable all patients and relevant healthcare professionals’ access to their immunisation records to enable ‘opportunistic vaccination’. We also propose joint controllership over data between GP surgeries (who currently act as controllers and processors of data) and NHS England, to enable access for anonymised personal information for clearly defined purposes. As a priority, community pharmacy should be able to access patient records in order to support ‘opportunistic vaccination’ in the community. This move would also be a key component of a wider shift to ‘patient managed’ records, a move commensurate with commitments in the Government’s recent Plan for Digital Health and Care and the Integration White Paper, both of which call for the NHS App to offer a personalised experience and to encourage them to engage in tailored preventative activity (including immunisations and vaccinations).10A plan for digital health and social care, Department of Health and Social Care, 29 May 2022 [link]; Health and social care integration: joining up care for people, places and populations, Department of Health and Social Care, 9 February 2022 [link] The Vaccine Data Resolution Service (VDRS) should become more accessible to users so they can help to ensure records are up to date.

Engaging Citizens

- Additional functionality should be added to the NHS App – building on the commitment made by the previous Secretary of State for Health and Social Care which called for all COVID vaccinations to be bookable via the App by March 2023. The aim should be to ensure that service users (or relevant nominated persons) can access full ‘life course’ immunisation records, as well as having the ability to book and manage immunisation appointments.

- These developments should incorporate the existing work on developing a Digital ‘Red Book’ and embed the current ‘Birth to Five’ resource.11‘Digital revolution to bust COVID backlogs and deliver more tailored care for patients’, Gov.uk, 29 June 2022 [link] As part of an extended digital offer, e-Consent for childhood and school age immunisation should be offered to patients and carers wherever possible (and should accompany paper-based approaches in a longer-term transition to a predominantly digital approach). To mitigate digital exclusion, this information should be available via multiple channels, with paper-based resources remaining in place.

- Interest and user engagement in vaccines research should be strengthened by NHS England and the NIHR through the development of a comprehensive Vaccine Research Registry, modelled on the COVID-19 Vaccine Registry. Such an approach was genuinely world-leading during COVID-19 and ought to be expanded to support NHS partnerships with the life sciences sector.

- A coalition of charity and voluntary sector organisations should establish a Life Course Immunisation Advocacy group. This new organisation would provide information, act as the public champion and advocate for all immunisation programmes. This could emerge as a federation of existing Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations to ensure resources are pooled most effectively.

- Vaccine disinformation should be monitored and countered with the development of a permanent communications cell in the NIS, working closely with DHSC and feeding into the DCMS Counter Disinformation Unit. This should be modelled on the Rapid Response Unit introduced by the Cabinet Office during COVID-19 and should provide monitoring and asset creation to assist local providers tailor their own communication strategies and to deploy their own disinformation measures.

Assessment and Regulation

- Reforms should be introduced to modernise the approaches and workings of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). These should be reflected in an updated JCVI Code of Practice. To support its world-leading work, the JCVI (and UKHSA) requires additional support. A busy ‘late stage’ vaccines pipeline means that demands placed upon it will be great in the coming years. Evolutionary changes to its workings should look to capture the positive learnings from the pandemic, by creating a stronger predictive arm, a more transparent decision and process architecture with the aim of enhancing dialogue with industry and key stakeholders, including NHS England. Changes would include:

- The establishment of a dedicated ‘Horizon Scanning Sub-Committee’, with a remit to look up to 10 years ahead (the current horizon scanning process looks at vaccines in development over the next 3-5 years). The sub-committee should be encouraged to ‘direct the horizon’ with demand signalling mechanisms which determine the nationally significant vaccine-preventable diseases. Representation on the sub-committee should include epidemiologists but may also draw upon the input of representatives from the Accelerated Access Collaborative, BEIS, DHSC and NHS England.

- An expansion of the opportunities for patient and public involvement.

- A refreshed approach to engagement with manufacturers, with routes created to allow for informal two-way dialogue to supplement company days.

- A clear timeline for the assessment of new vaccine candidates including a process chart which should be published on the JCVI website.

- Additional resource to ensure the JCVI can meet this expanded remit. As set out in the terms of reference, this should enable an expansion of the secretariat headcount, with emphasis on expertise in communications, horizon scanning and modelling.

Introduction

This report explores the future of vaccines policy in England. At a time when we are spending more on the NHS than ever before to meet increasing demand and growing complexity, immunisation remains the vanguard of preventative healthcare. Unlike other totemic public health issues such as obesity or smoking, there is a consensus both within Government and across mainstream political parties on the value of immunisation and the need to improve performance.

It would be legitimate to argue that routine vaccination should be afforded the same priority as waiting list backlogs, ambulance handovers, or appointments in general practice. Public health is connected to all these issues, and the value of vaccination for the NHS – and indeed the broader economy – is difficult to overstate. Whilst representing a cost to the taxpayer in the first instance, longer-term savings are derived through significant reductions in health costs and through the avoidance of productivity losses across the workforce.12Sachiko Ozawa & Samantha Clark et al., ‘Return on Investment from Childhood Immunization In Low- And Middle-Income Countries, 2011–20’, Health Affairs, Vol. 35, No. 2 (February 2016) [link] By Autumn last year, COVID jabs had – by the Government’s estimation – prevented over 100,000 deaths and at least 230,000 hospitalisations.13COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report published, Gov.uk, 14 May 2021 [link] That is before you consider the value routine immunisation programmes in their totality: of HPV vaccines in reducing incidences of cervical cancer; or Hepatitis B for cancers of the liver.14Till Bärnighausen & David E. Bloom et al., ‘Valuing vaccination’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 111, No. 34 (2014), 12313-12319 [link] Success across the UK has ripple effects with effective immunisation playing an important role in reducing the global burden of disease.15 Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind, World Health Organization [link]; Lawrence D. Frenkel, ‘The global burden of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases in children less than 5 years of age: Implications for COVID-19 vaccination. How can we do better?’, Allergy and Asthma Proceedings, Vol. 42, No. 5 (2021), 378-385 [link]

| ‘Vaccination’ or ‘immunisation’? |

‘Vaccination’ and ‘immunisation’ mean slightly different things, despite being used interchangeably in this report.

|

Declining performance

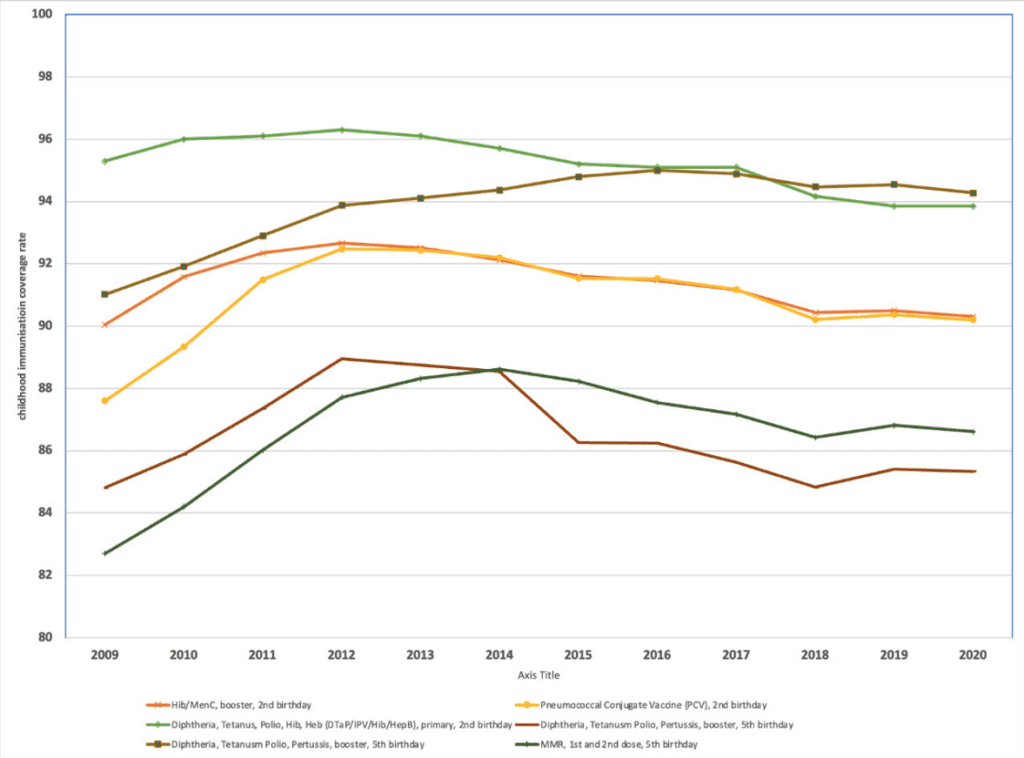

Graph 1. Childhood immunisation coverage, England, 2009/10-2020/21

Source: Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics, NHS Digital [link]

However, many routine programmes have witnessed declining uptake in recent years (see Graph1.). Within pre-school vaccinations, NHS England has missed every DHSC performance standard for uptake since 2012/13.16‘Investigation into pre-school vaccinations’, National Audit Office, 25 October 2019, p. 7 [link] In several instances, the picture of decline has been exacerbated by the pandemic.17Caitlin Tilley, ‘Decline in children receiving jabs for diseases other than Covid’, Pulse, 3 September 2021 [link] This aligns with a broader, global trend. For a comprehensive analysis, see Anita Shet, Kelly Carr & M Carolina Danovaro-Holliday, ‘Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services: evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries and territories’, The Lancet Global Health, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2022), 1-9 [link] and Kaja Abbas & Vittal Mogasale, ‘Disruptions to childhood immunisation due to the COVID-19 pandemic’, The Lancet, Vol. 398, No. 10299 (7 August 2021), 469-471 [link].

For evidence of disruption in a Canadian context for instance, see Hannah Sell, Ali Assi & S. Michelle Driedger et al., ‘Continuity of routine immunization programs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Vaccine, Vol. 39, No. 39 (15 September 2021), 5532-5537 [link]. Programmes in Sweden maintained high levels of uptake however by comparison. See Kathy Falkenstein Hagander, Bernice Aronsson & Madelene Danielsson et al., ‘National Swedish survey showed that child health services and routine immunisation programmes were resilient during the early COVID-19 pandemic’, Acta Paediatrica, Vol. 110, No. 9 (June 2021), 2559–2566 [link]. MMR vaccine uptake has fallen to its lowest level for a decade, with coverage for the two doses in five-year-olds currently 85.5% (2020-21), well below the 95% World Health Organisation target needed to achieve and sustain measles elimination.18‘England: MMR vaccination awareness drive as uptake drops to lowest level in a decade’, Community Practitioner, 18 March 2022 [link] As Professor Helen Bedford and Helen Donovan have noted, this means that more than 1 in 10 children under the age of five are not fully protected from measles and are at risk of catching it.19Helen Bedford & Helen Donovan, ‘We need to act now to improve childhood vaccine uptake’, Institute of Health Visiting, 25 February 2022 [link] This led to the launch of a national campaign to remedy the situation in February 2022.20‘Around 1 in 10 children starting school at risk of measles’, Gov.uk, 1 February 2022 [link] Whilst there has been a shift in discourse around immunisations to encompass a ‘whole-of-life’ or ‘life course’ approach, coverage for some adult risk groups remains sub-optimal. The recent re-emergence of polio in sewage in East London (and the recommencement of a booster programme) as well as the recent outbreak of monkeypox reinforces the fragility of disease control and the need for a renewed approach.21Joe Pinkstone, ‘Polio vaccine will be offered to London children after virus found in sewers’, Daily Telegraph, 10 August 2022 [link]; Daniel M. Davis, ‘A little more vaccination: Elvis Presley and the race to beat polio’, The Times, 26 June 2022 [link]. Accordingly, recent JCVI minutes published on 5th August 2022 made a recommendation to move MMR2 to 18 months in order to increase VCRs and prevent potential outbreaks [link]

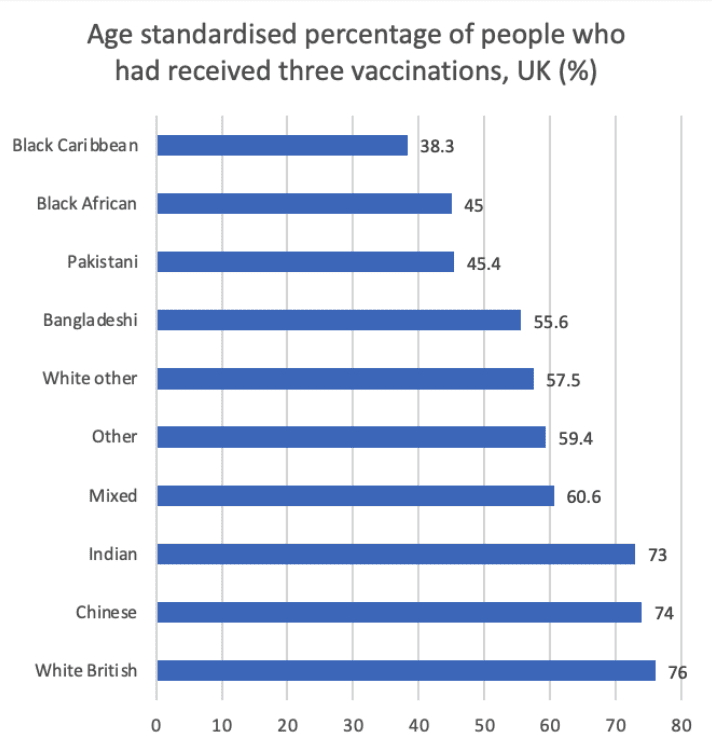

The general trend has been a decline in uptake across routine programmes, but this picture is varied across the country.22Investigation into pre-school vaccinations, National Audit Office, 25 October 2019 [link] Whilst there are long-standing challenges in London, despite early concerns, infant and preschool immunisation uptake increased in Scotland over the lockdown period.23Fiona McQuaid, Rachel Mulholland & Yuma Sangpang Rai et al., ‘Uptake of infant and preschool immunisations in Scotland and England during the COVID-19 pandemic: An observational study of routinely collected data’, PLoS Medicine, Vol. 19, No. 2 (February 2022), 1-18 [link] The current data also suggests there are particularly low levels of uptake amongst certain geographic, socioeconomic, ethnic and religious groups across England; many of whose healthcare needs are underserved more broadly.

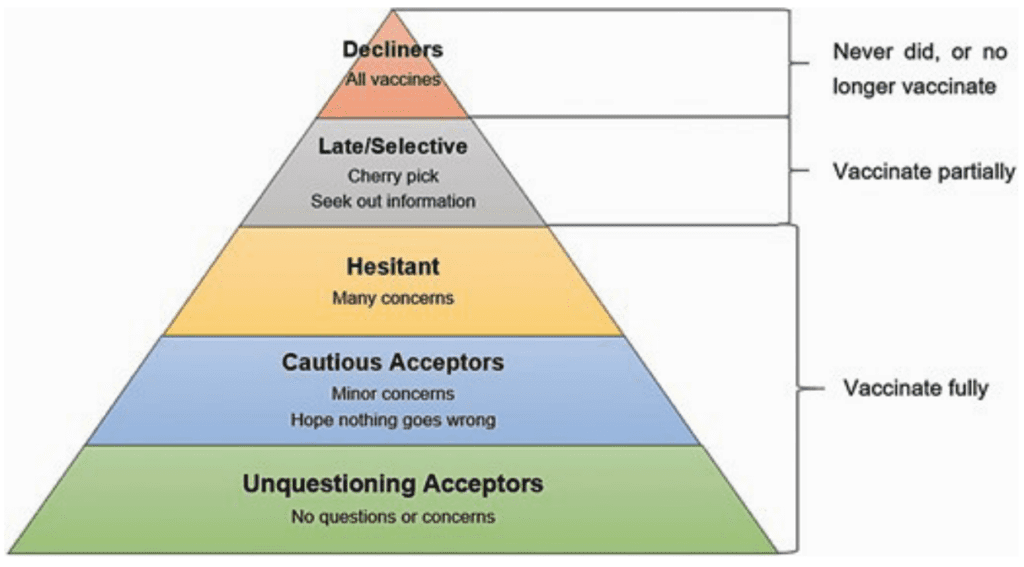

Whilst an overall trend in declining uptake is clear to see, what is less easily quantified are wider trends in vaccine confidence. Many healthcare professionals report confidence issues affecting uptake across childhood programmes, or ‘vaccine fatigue’ setting in. This necessitates a focus on baking in best practice undertaken by local government, PCNs and individual GP practices in reaching underserved communities and in effectively tailoring campaigns to meet need.

A renewed focus

The experience of the pandemic has encouraged a fresh look at immunisation services in the round. As England enters a new phase of our response to the pandemic, it is expected that the deployment of the COVID-19 vaccine will be folded into the current schedule.24COVID-19 autumn booster and flu vaccine programme expansion, NHS England, 15 July 2022 [link] This presents an opportunity to bring key learnings and to replicate them across the routine programmes, where applicable.

The factors that enabled a successful immunisation campaign are clear to see: focused and clear leadership; a sense of mission and speedy decision-making; supply chain resilience; workforce preparedness; localised strategies to target underserved communities.25Nicholas Timmins & Beccy Baird, The Covid-19 vaccination programme: Trials, tribulations and successes, The King’s Fund, January 2022 [link] A spotlight was also shone upon the world leading characteristics of the UK’s life sciences and healthcare sector. The Vaccines Taskforce (VTF) acted ‘decisively and cost-effectively’.26Government’s Vaccines Taskforce has worked “decisively” and at “great pace” to improve UK’s pandemic preparedness, Gov.uk, 8 December 2020 [link]; For a review of the VTF, see UK Vaccine Taskforce 2020 Achievements and Future Strategy: End of year report (December 2020) [link]. The VTF will shortly be merged UK Health Security Agency and the Office for Life Sciences, see ‘Vaccine Taskforce to merge with UKHSA and OLS’, Gov.uk, 15 June 2022 [link] The pandemic also encouraged innovation, much of which would not have occurred at the equivalent pace in ‘peacetime.’ From novel approaches to enable easier, granular data sharing (Control of Patient Information, or COPI), to arrangements to enable primary care providers to delivery vaccines in novel settings, such as supermarket car parks or large workplaces, the best of these initiatives should be replicated – where suitable – across other programmes. But ‘initiative decay’ is a real risk.27Datapwa Mujong, ‘Will reached communities become ‘hard to reach’ again?’, British Journal of General Practice, Vol. 71, no. 713 (2021) [link] Where engagement with underserved communities for instance was short-term and limited to COVID-19 vaccine deployment, fatigue and mistrust may arise in the future. The pandemic also represented a paradox with some disciplines experiencing a high level of command and control, whereas others were liberated from reporting requirements and encouraged to innovate in ways to better suit their local circumstances. As we learn to live with COVID-19, we need to find a new way of liberating and empowering those on the front line. This must be done in a sustainable way and should include strengthened national enablers in key areas such as data, workforce planning and resourcing.

There has been a sense for a number of years that the architecture of immunisation could be improved. Different Government departments and arm’s length bodies are responsible for elements of procurement, development and delivery (See Figure 1). Moreover, whilst ICSs have now been placed upon a statutory footing, questions remain as to how the work of Regional teams, primary care providers and local authorities will link with that of ICSs; whilst the VTF was heralded as a major success in tackling the pandemic, representing particularly strong performance in the procurement of vaccines and in engagement with manufacturers, there is a risk that folding the body into a joint UKHSA-OLS body may reduce its and agility – two features which underpinned its early success.28Government’s Vaccines Taskforce has worked “decisively” and at “great pace” to improve UK’s pandemic preparedness, Gov.uk, 8 December 2020 [link] As its former head has recently stated, there is a risk that the organisation takes its “foot off the gas” in finding innovative new ways to prevent the spread of Covid-19.29Jim Dunton, ‘Kate Bingham warns officials have ‘lost focus’ on new Covid jabs’, Civil Service World, 31 August 2022 [link]

Figure 1 – Current governance architecture for vaccines and immunisation in England

In January 2022, the former Secretary of State for Health and Social Care mooted the introduction of a ‘National Immunisation Service’. Work has now begun within NHS England to develop an ‘integrated vaccination and immunisation strategy’.30Letter from Steve Russell and Nikki Kanani to ICB Chief Executive Designates, NHS England, 22 June 2022 [link] The objectives are to reduce disparities in uptake by making vaccination more convenient and accessible, and to reduce the impact of vaccine deployments on ‘core’ GP services. There is a real possibility of quite substantial changes to the way in which vaccines policy is developed and how campaigns are organised as a result, depending upon how this work proceeds.

In that context, this report considers the future of routine vaccines delivered across the life course, assessing the impact of the slow catch-up over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic upon routine programmes, before setting out a series of proposals to improve coverage and to provide an improved service for users.31Tim Crocker-Buque & Sandra Mounier-Jack, ‘Vaccination in England: a review of why business as usual is not enough to maintain coverage’, BMC Public Health, Vol. 18, No. 1351 (2018) [link]

The structure of the report is as follows:

- Chapter 1 – Explores the historical and current immunisation policy context. It assesses the value of vaccination, through an analysis of the impact of reductions to the uptake of MMR and shingles vaccines during the early stages of the pandemic.

- Chapter 2 – Provides our assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon vaccines policy

- Chapter 3 – Sets out our vision for the design of vaccination and immunisation services in England, bringing together the key insights and findings from our research. This covers off the following core thematic elements of the programmes:

- Governance and Delivery Models

- Workforce

- Data

- Engaging Citizens

- Assessment and Regulation

- Conclusions

Methodology

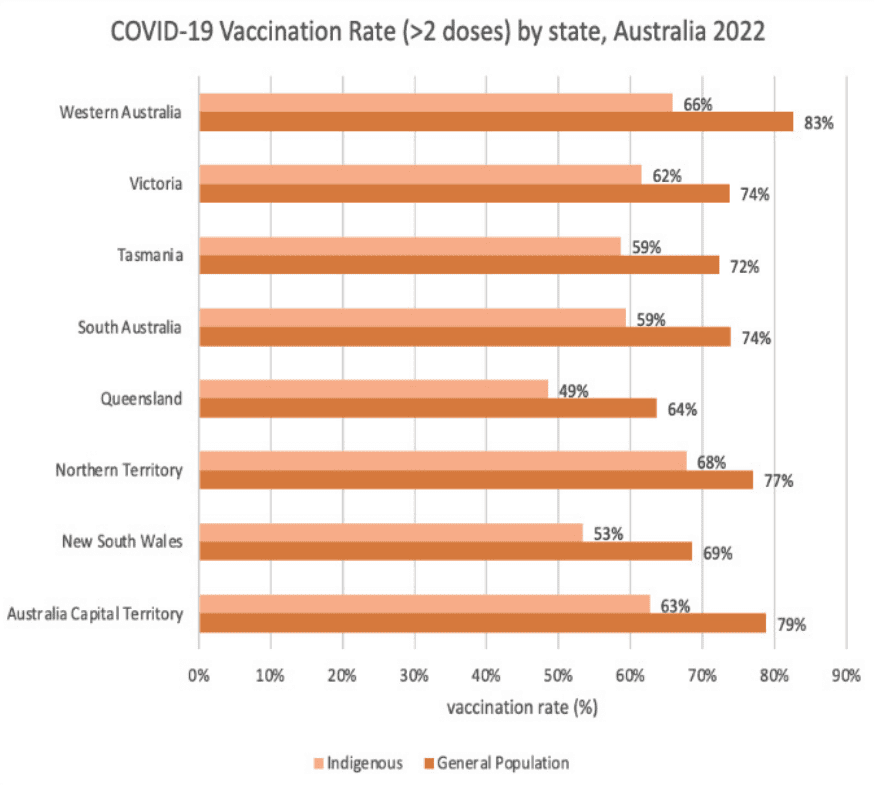

We collected insights and tested our findings through semi-structured interviews with over 40 immunisation experts, policymakers, industry representatives, and international organisations between May and October 2022. These interviews included experts from Belgium, Portugal, and Australia to learn from innovative approaches to increase immunisation uptake internationally, as well as to learn from their experiences in horizon scanning and the evaluation of novel vaccine technologies. We also carried out two roundtables in May and June: one focused on the experiences within England; the other on international best practice respectively. We complemented these interviews and roundtables with a comprehensive literature review.

As part of this work, we have also undertaken a quantitative analysis of publicly available data to estimate the potential public health impact (in terms of case reductions and mortality) of increased uptake of MMR and shingles vaccines. These two programmes were chosen to represent impacts across the life course, given they are targeted at different demographic groups (childhood and adult).

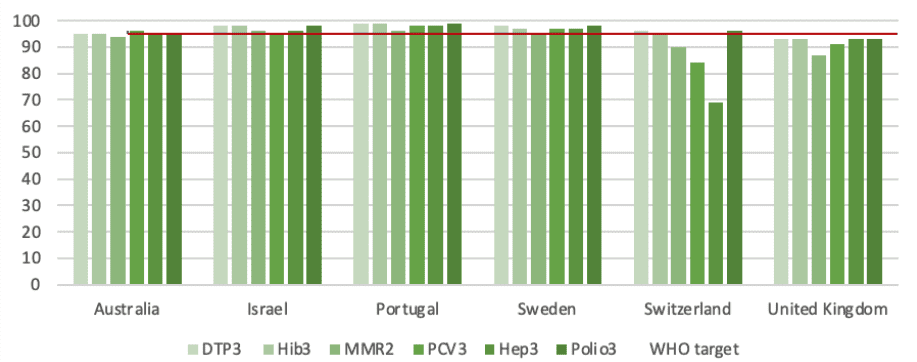

In each section of this report, we also look at international immunisation approaches taken in five different countries that have achieved high routine childhood vaccination rates (See Graph 2.) These include Australia, Israel, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland. We understand that each of the selected health systems are highly diverse in their organisational structures, operations, and political and economic characteristics. We do not therefore attempt to compare nor benchmark the performance of these countries but to draw upon insights from these high-performing healthcare systems.

Graph 2. Childhood immunisation uptake across five comparator countries

UNICEF (2019) [link]

Next chapterChapter 1 – Policy Context

In this chapter, we consider the structure of immunisation programmes in England and their development over time. We also explore the extent to which COVID-19 exacerbated the decline in uptake across routine programmes using Shingles and Measles coverage data as case studies to evaluate the number of cases that can be prevented annually if coverage were to achieve the WHO target of 95%.

England’s Immunisation Programme

Immunisation is widely considered as one of the greatest global health achievements in history––the WHO estimates that vaccines save 4-5 million lives per year.32Xiang Li, Christinah Mukandavire & Zulma M Cucunubá et al., ‘Estimating the health impact of vaccination against ten pathogens in 98 low-income and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2030: a modelling study’, The Lancet, Vol. 397, No. 10272 (2021), 398-408 [link] Immunisation is not only an extremely effective public health measure – with most vaccines producing immunity in over 90% of those vaccinated – but also cost-effective, benefitting not only those with direct protection, but others in their families and communities.

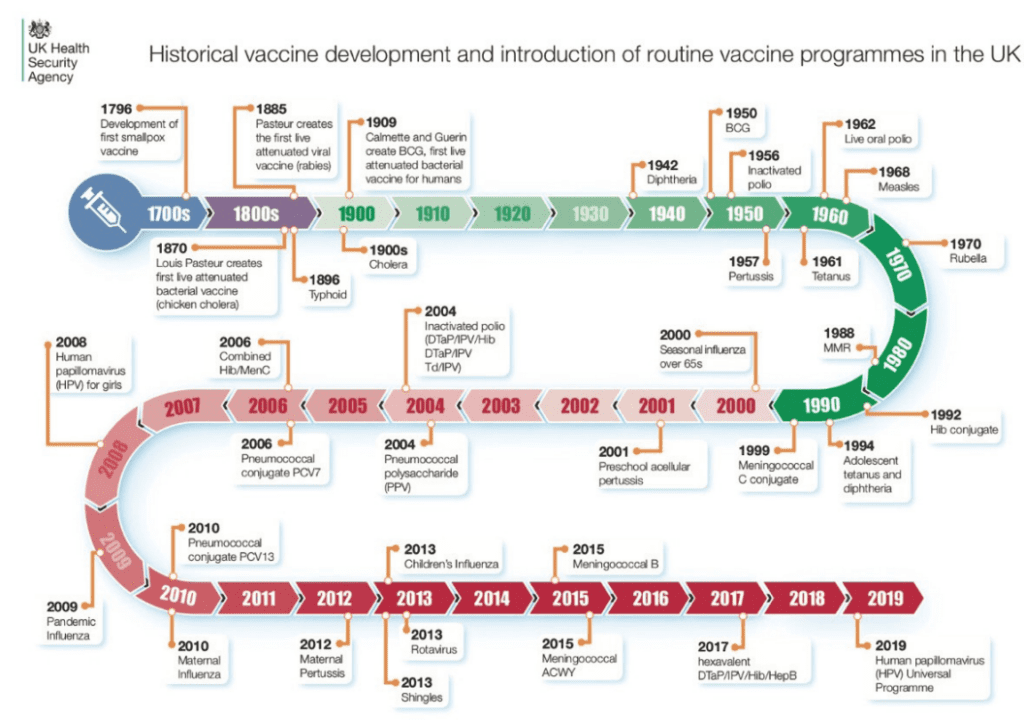

Life-threatening diseases such as diphtheria, whooping cough and polio used to be highly prevalent in children in the UK and are now extremely rare. In 1942, there were 50,804 diphtheria cases in England and Wales; now there is just one case a year on average (although its recent discovery at Manston asylum centre in November 2022 is a current cause of concern).33‘Manston asylum centre death may have been caused by diphtheria’, The Guardian, 26 November 2022 [link] There were 92,407 cases of whooping cough per year in 1957; now the incidence per year is 3,506. A recent study published in The Lancet has found that the HPV immunisation programme has almost eliminated cervical cancer in women born since September 1995.34Milena Falcaro, Alejandra Castañon & Busani Ndlela et al., ‘The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study’, The Lancet, Vol. 398, No. 10316 (2021), 2084-2092 [link] Figure 2 depicts the steady increase in vaccines which have been added to the routine schedule over time.

These interventions are significant in supporting population health and ensuring health systems are not placed under greater stress domestically, but the benefits of vaccination stretch far beyond healthcare spending to include wider economic, educational and health security benefits.35Peter Piot, Heidi J. Larson & Katherine L. O’Brien et al., ‘Immunization: vital progress, unfinished agenda’, Nature, Vol. 575, 119–129 (2019) [link] One study found that health protection interventions such as vaccines deliver a £34 return for every £1 invested.36Rebecca Masters, Elspeth Anwar & Brendan Collins et al., ‘Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review’, Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, Vol. 71, No. 8 (2017), 827-834 [link]

Currently, sixteen vaccines and immunisations are offered on the NHS across the ‘life course’ (see Table 1). These are all ‘preventative’ vaccines, predominantly administered to healthy individuals. With Covid-19 vaccinations to be incorporated into routine immunisation programme in Wales, it is likely that a similar approach will be adopted in England in due course.37Emma Wilkinson, ‘Covid vaccinations to be incorporated into routine immunisation programme in Wales’, Pulse, 24 February 2022 [link] New vaccines in the pipeline are assessed and advise upon their use determined by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), an independent expert advisory committee. Its role is discussed in further detail in Chapter 3.

Figure 2. Vaccination Timeline from the 1700s to present day

Source: ’Vaccination timeline infographic from 1796 to present’, UK Health Security Agency [link]

Table 1. Complete Routine Immunisation Schedule: Childhood, Adolescent, and Adult Programmes Delivered by the NHS in England

| Vaccine | When is it offered? | Where is it offered? |

| Babies under 1 year old | ||

| 6-in-1 vaccine (DTaP/IPV/Hib) | 8 weeks | GP surgery; local child health clinic

|

| Rotavirus vaccine | ||

| MenB | ||

| 6-1 vaccine (2nd dose) | 12 weeks | GP surgery; local child health clinic

|

| Pneumococcal (PCV) vaccine | ||

| Rotavirus vaccine (2nd dose) | ||

| 6-1 vaccine (3rd dose) | 16 weeks | GP surgery; local child health clinic |

| MenB (2nd dose) | ||

| Children and Adolescents 1 to 15 | ||

| Hib/MenC (1st dose) being discontinued | 1 year | GP surgery; local child health clinic

|

| MMR (1st dose) | ||

| PCV (2nd dose) | ||

| MenB (3rd dose) | ||

| Seasonal flu vaccine (Influenza) (every year) | Eligible age groups | GP surgery (6 months to primary school), School (primary school, year 7-11), Community clinic (home-schooled children) |

| MMR (2nd dose) | 3 years and 4 months | GP surgery; local child health clinic |

| 4-in-1 pre-school booster (DTaP/IPV) | ||

| COVID-19 vaccine (1st and 2nd dose) | 5 to 15 years

|

GP surgery, vaccination centre, pharmacy, walk-in vaccination sites (without appointment), school |

| HPV | 12 to 13 years | GP surgery, school |

| 3-in-1 teenage booster (Td/IPV) | 14 years | Secondary school |

| MenACWY | ||

| Adult | ||

| COVID-19 vaccine (1st, 2nd and booster) | 16 years and over | GP surgery, vaccination centre, pharmacy, walk-in vaccination centre |

| Flu vaccine | 50 years (and every year after)38It remains undecided (at the time of writing) whether the 65+ cohort will be lowered for 2022-23 to include 50-64 years (this may need to be updated to 65 years and every year after as a result). | GP surgery, pharmacy |

| Pneumococcal (PPV) vaccine | 65 years | GP surgery, pharmacy |

| Shingles vaccine | 70 years | GP surgery, pharmacy |

| Pregnant Women | ||

| Flu vaccine | During flu season | GP surgery, pharmacy |

| Whooping cough (pertussis) vaccine | From 16 weeks pregnant | GP surgery, antenatal clinics |

Source: The complete routine immunisation schedule from February 2022, NHS England [link]

In England, the coordination of immunisation programmes involves a wide range of organisations, and consequently, as one recent study describes it, the system is “a complex mesh”39Tracey Chantler, Saumu Lwembe & Vanessa Saliba et al., “It’s a complex mesh”- how large-scale health system reorganisation affected the delivery of the immunisation programme in England: a qualitative study’, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 16, No. 489 (2016) [link]. The national strategy and performance targets are set by DHSC with advice from the independent JCVI and the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM); programmes are commissioned by NHS England; procurement and surveillance is undertaken by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), forming a tripartite organisational structure that relies on ’joint responsibility.’ DHSC does not itself deliver vaccination programmes. Under the NHS Public Health Functions Agreement (Section 7A), DHSC delegates responsibility for delivering national immunisation programmes to NHS England. The latter then commissions vaccination services to GP surgeries, School Age Immunisation Services (SAIS), or community pharmacy, depending on the target population. Pre-school and adult vaccinations are usually delivered by GPs surgeries, commissioned through the GP contract. School-age services are commissioned by seven Regional NHS England teams, delivered through SAIS. Coordinating a national immunisation programme that serves a large and diverse population of 56 million is not an easy task, and as our report will explain, England’s immunisation programme suffers from fragmentation as a result.

Across the UK, immunisation programmes – as with the rest of health services – are devolved. This report focuses upon England’s experience, but Box 1 provides a summary of how programmes across the four devolved nations have recently differed.

| Box 1. Immunisation Programmes Across the UK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How do immunisation programmes differ across the UK?

Prior to political devolution in 1999, the administration of each health service in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland was the responsibility of the respective Secretary of State.30 However, the convention of collective responsibility of the Cabinet potentially limited the Secretary of State for Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales to pursue policies that diverged from those applying to England. Table 2 illustrates the different organisations responsible for immunisation programmes across the UK. Table 1. Overview of organisations involved in immunisation across nations

Scotland: The Vaccination Transformation Programme (VTP) Whilst the majority of programmes were administered through general practice, in 2017, the Scottish Government and the Scottish General Practitioners Committee (SGPC) agreed vaccinations would move away from GP-based delivery to one based on NHS Board/Health and Social Care Partnership (HSCP) delivery through dedicated teams (as part of an effort to reduce GP workload)40Vaccination Transformation Programme, Public Health Scotland [link] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wales

The Department of Health and Social Services in Wales sets expectations for NHS Wales to deliver and commission routine immunisation programmes, provided as nationally contracted services. The call/recall system is centralised, using a national birth registration-based system that generates named postal invitations sent to home addresses. 41Richard J. Roberts, Anne McGowan, and Simon Cottrell, ‘Measuring inequalities in immunization in Wales and the impact of interventions’, Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, Vol. 12, No. 10 (2016), 2704–2706 [link] In October 2022, a National Immunisation Framework for Wales was published.42National Immunisation Framework for Wales, Welsh Government (October 2022) [link] Northern Ireland Immunisation policy in Northern Ireland is planned by the Department of Health (Northern Ireland), commissioned jointly by the Public Health Agency (PHA) and Health and Social Care Board and predominantly delivered through GPs and schools. It has a more centralised approach to the English system whereby the PHA is responsible for both the commissioning and surveillance of national vaccine programmes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

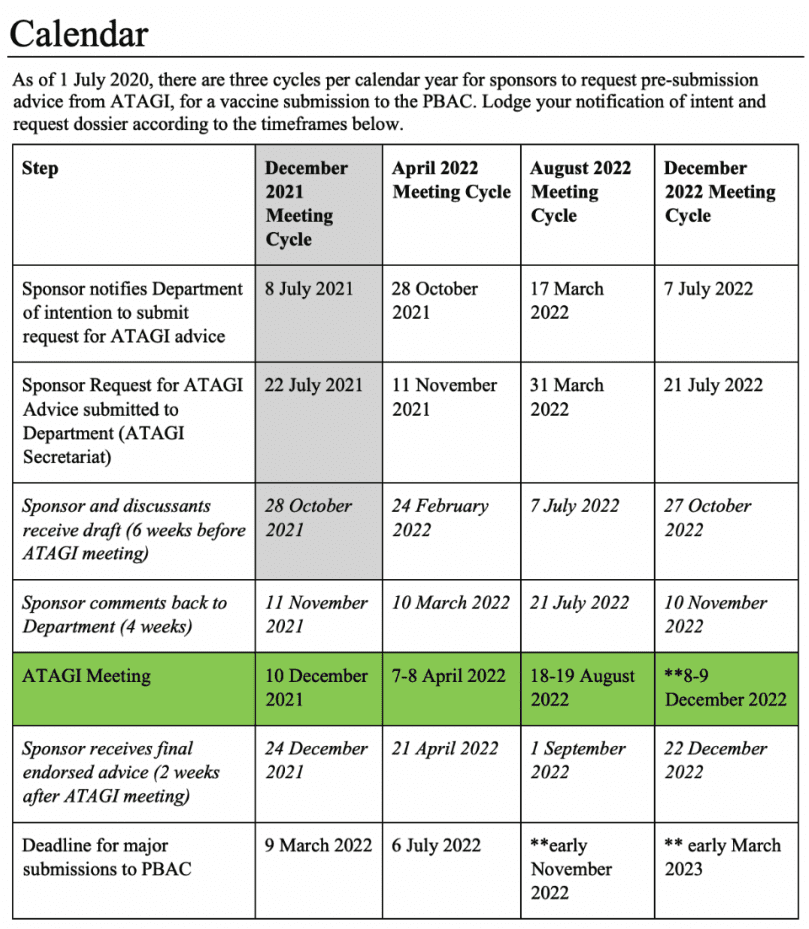

| Summary