Gerard Lyons

Senior Fellow

“My Government’s priority is to grow and strengthen the economy and help ease the cost of living for families.” These opening two lines of the Queen’s Speech provided a powerful message.

Further action is needed to address the cost of living crisis. Also, those affected are not just families, but the vast bulk of households that are being squeezed. If the Government doesn’t appreciate this, then it may have its work cut out.

To its credit, the Government has already announced a host of targeted measures. These include a £150 refund on council tax for those in bands A to D. While welcome, the gains are partially offset by a rise in the average Council Tax in band D of £67.

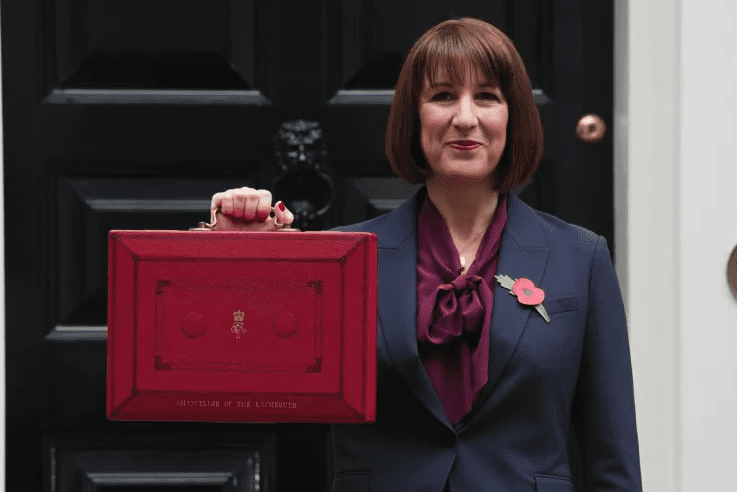

The main help by far, though, was announced by the Chancellor in the Spring Statement – an increase in the threshold at which the higher rate of national insurance is to be paid. This has now been aligned with the starting threshold for income tax, around £242 per week. There is also the expectation that the Government will act again, as energy bills are expected to rise again this autumn, when the new price cap kicks-in.

Indeed, the cost of living crisis looks set to get worse, before it gets better. UK inflation is set to peak soon, probably above 10 per cent, and will then stay elevated for some time. While inflation is set to decelerate next year, it seems unlikely to return to its two per cent target anytime soon.

It also vital to appreciate that we are very quickly moving away from the main problem being inflation to it being a lack of economic growth. There thus needs to be a reiteration of a clear, executable vision and strategy to grow and strengthen the economy. But first, the cost of living crisis merits further attention.

High fuel and food prices are already exacerbating problems for lower income households, who spend a higher proportion of their income on these areas. At the same time, a large part of peoples’ disposable incomes fund their housing costs. Furthermore, as the retail price index heads higher, rail fares will rise, and changes earlier this year added to the cost of repaying student loans.

While some have savings they can dip into, many don’t. Thus, overall, discretionary spending will be squeezed with widespread negative consequences for retailers and many firms. In turn, there will be upward pressure on costs, prices and wages.

Even the labour market, where unemployment is low, could see change since a sharp economic slowdown is likely, including the possibility of a technical recession with two successive negative quarters of economic growth.

The challenge is that, surely, the Government can’t go on spending taxpayers’ money at every sign of trouble? That is right – but downside economic risks mean intervention is needed, not only to ease the burden but also through low taxes to revitalise growth. The situation also highlights the need to restore both fiscal and monetary stability, once the economy allows, allowing scope to cope with future shocks.

The economic and political shock-absorber is a looser fiscal policy over the next year. Although the budget deficit is higher than one would like, the good news is that it is falling sharply: from £317.8 billion in 2020/21 to £151.8 billion in 2021/22, and is expected by the Office for Budget Responsibility to decline further to £127.8 billion in 2022/23. Moreover, higher inflation is already bolstering tax receipts.

So what should be done? Relaxing fiscal policy and targeted support should not add to inflation since demand is already slowing. Targeted help is needed for those on low incomes, but also there is a need to help the squeezed middle.

Other countries have enacted policies to shield people from rising energy prices, including reduced taxes on energy or VAT; retail price regulation; wholesale price regulation; transfers to vulnerable groups; mandating firms’ behaviour; windfall profits tax; business support; or other measures (such as cutting the green levy in Germany).

While other countries, too, are tightening monetary policy, the UK is unusual in that it is squeezing fiscal policy. Benefits, for instance, were not raised in line with higher inflation in the Spring Statement, when perhaps they should have been. Crucially, the tax take is at an all-time high. The latter needs to be reversed. It includes too many people being dragged into higher tax brackets, and this can only be addressed by raising tax allowances and the levels at which people enter higher tax bands.

Quickly executable targeted measures could include a further increase in the Council Tax rebate. Another would be to use Universal Credit to direct more money to those in most need, while preserving work incentives. A mid-year rerating of benefits to raise them in line with higher inflation may take longer to implement but is another option

Temporary removal of some of the permanent components of fuel duties should be considered although, like many of these measures, further cuts in taxes on energy are not cheap. The temporary five pence cut in fuel duty is set to cost £2.4 billion this fiscal year. Suspending VAT on domestic energy while gas prices remain high has been suggested by some MPs.

Another possible but unlikely option is a temporary suspension of the environmental levy paid on energy bills. It would not, in my view, compromise the Government’s commitment to the green agenda, and could free up about £340 per household per year. The importance of addressing climate change is critical; it is peoples’ ability to pay that is the issue.

There is a clear case for bringing forward the one pence cut in income tax that has been pencilled in for before the next election. The Treasury calculates that this will costs £5.4 billion in its first year, but it would address an important issue in that income tax collection is now heavily concentrated, with roughly four in ten adults only paying it. A broader tax base with low tax rates makes more sense, but that may be a future aim.

There is also a search for non-fiscal measures that can help businesses and households. Measures that both ease the burden on firms and employers, while bolstering their confidence about the future, should figure prominently.

The most obvious is to implement supply-side measures from the Taskforce on Innovation and Growth Report. Although some may take time to feed through, they should bolster business confidence and encourage investment.

Also, measures to turbo-charge the housing market are welcome. Planning reform, while necessary, appears to have taken a back burner. A year ago, in a research paper for Policy Exchange, I outlined measures on the demand side that could help Generation Rent become Generation Buy, including allowing those who cannot afford deposits to use their history of regular rent payment to enter the housing market.

If the economic climate deteriorates, banks should be encouraged to exercise forbearance on loans if firms encounter difficulty. The Bank of England should also re-examine prudential requirements to ensure that these are not having a negative impact on growth.

This proactive policy response to address immediate challenges is complimentary to other areas of policy. It should not threaten the inflation outlook. Crucially, it is consistent with the existing fiscal strategy of reducing the ratio of debt to GDP from its present level of 96.2 per cent and the aim to achieve a significant improvement in the public finances. Strengthening the economy is the aim, easing the cost of living crisis is the immediate focus.

This article was originally published in ConservativeHome