In my recent report on air pollution in London, I argued that the new Mayor of London needs to create and deliver a more ambitious plan to clean up London’s air. At the same time, I recommended that this should be done in ways which do not unduly penalise local residents and businesses; that coordinated action is needed at London, national and European level to tackle the problem; and that action is needed on both road transport and other sources of pollution.

So how do Sadiq Khan’s proposed measures, outlined on the 5th July, stack up against these principles?

The new measures certainly are ambitious. In fact, the Mayor of London has himself described this as the ‘toughest crackdown on the most polluting vehicles by any major city around the world’. But are the measures fair and proportionate? Or will they penalise residents and businesses?

T-Charge

The first proposal is for a new Emissions Surcharge (dubbed the ‘T-charge’) to be levied on more polluting vehicles entering central London from 2017. The charge would apply to all vehicles with pre-Euro 4 emission standards (broadly speaking those registered before 2005) and cost an extra £10 per day on top of the existing Congestion Charge.

As currently defined, the T-charge would have a significant financial effect on a large number of motorists. TfL statistics show that around 5.8 million unique vehicles enter the Congestion Charge Zone each year, including 5 million cars (this includes all vehicles, whether they enter the zone daily or just from time to time), and 0.8 million vans, HGVs, buses and coaches. Using DfT statistics on vehicle age by type, we estimate that the T-charge would apply to around 1 million cars, and 0.2 million vans, HGVs, buses and coaches each year (before the effect of any change in behaviour to comply with the standards). For those who live, work or commute into the CCZ on a regular basis, the T-charge could result in a very sharp increase in travel costs. These motorists bought their vehicles in good faith – as for at least the last 15 years, Government has been promoting diesel vehicles on the grounds of their lower CO2 emissions. The air pollution impact of diesels needs to be acknowledged and dealt with, but the current proposal gives very little notice for the 1.2 million motorists affected to respond. This is likely to result in significant pushback from residents and businesses.

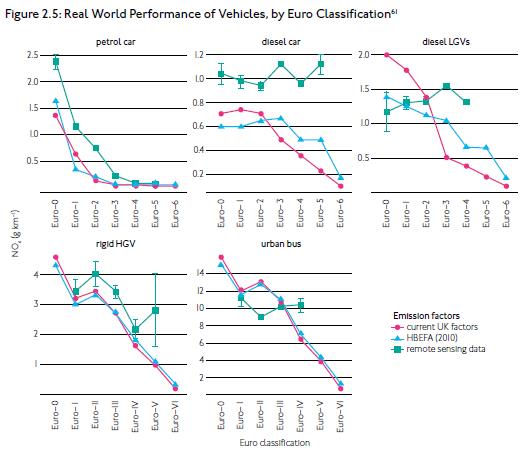

There are also issues in relation to the proposed emission standard – under which the T-charge would apply to all pre Euro 4 vehicles. On one hand, it is unclear why the cut-off for the T-charge is Euro 4, when Euro 4 and 5 diesels have higher NOx emissions than Euro 3 diesel cars (as shown in the chart below). Indeed, Euro 5 diesel cars have slightly higher emissions of NOx than pre Euro 1 diesels sold in the 1990s. On the other hand, the T-charge would apply to pre Euro 4 petrol vehicles, despite the fact that they have lower emissions than Euro 4 diesel cars which are exempt (e.g. 0.74g/km NOx for Euro 2 petrol, 0.22g/km for Euro 3 petrol, 0.96g/km NOx for Euro 4 diesel). In fact, Euro 3 petrol cars have lower emissions than the average Euro 6 diesel cars sold today. Overall, the proposed emission standard fails to target the right vehicles, makes no sense, and should be re-thought.

Source: Carslaw, D. et al (2011) Remote Sensing of NO2 exhaust emissions from road vehicles. Defra, cited in Howard, R. (2015) Up in the Air: How to Solve London’s Air Quality Crisis, Part 1. Policy Exchange

Furthermore, as currently designed, the T-charge could potentially have a disproportionate effect on poorer households and smaller businesses. Data from the National Transport Survey shows that car owning households in the lowest income quintile are nearly twice as likely to have a car over ten years old than households in the highest income quintile. Similarly, larger companies with corporate fleets and company car schemes are more likely to operate newer vehicles than smaller to medium sized enterprises. The distributional effects of the policy need to be considered further.

Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ)

The second set of proposals relate to the ULEZ scheme. The Mayor proposes to bring forward the implementation of the ULEZ by one year, from 2020 to 2019. This is a positive move, since it means that the scheme will be implemented within the current Mayoral term. The GLA will need to think through the potential interaction between the proposed T-charge and the ULEZ, since in a sense the T-charge is an acceleration of aspects of the ULEZ scheme.

The Mayor also proposes to extend the geographic coverage of the ULEZ significantly. As currently defined the ULEZ would cover the same area as the Congestion Charge Zone, in central London. The Mayor proposes to extend the ULEZ from 2020 to the North-South Circular for motorcycles, cars and vans; and London-wide for lorries, buses and coaches (to the area covered by the Low Emission Zone / M25). This would significantly increase the number of residents, businesses and vehicles covered by the scheme. The Congestion Charge Zone covers an area of 21 sq km and includes a resident population of 136,000 people. The N-S circular covers an area of around 380 sq km, and includes of population of several million people (we are not aware of any exact figures). The London-wide Low Emission Zone is much bigger again at 2,644 sq km, including a population approaching 9 million people.

There are many roads outside the current ULEZ/CCZ zone which are above the legal NO2 limits, and based on current plans would not come within these limits for a decade or more. At the same time, there are large areas within the N-S circular and M25 that are already well below the NO2 limit. The proposal to significantly expand the ULEZ may lead to changes to vehicles and travel patterns which are not required to meet compliance (i.e. where compliance has already been reached), creating an unnecessary burden on residents and businesses. Again, we would expect significant pushback on this proposal once stakeholders realise the implications.

There are also practical issues with expanding the ULEZ area, as highlighted in our recent report. Creating an additional charging zone (in addition to the existing CCZ and Low Emission Zone) could create confusion amongst motorists, and would also require investment in additional infrastructure such as an additional set of enforcement cameras. For that reason, we focused our recommendations on reforms to the existing emission zones, rather than creating new ones.

Pedestrianising Oxford Street

Alongside the main air quality consultation, the Mayor has also announced plans to pedestrianise Oxford Street by 2020. Whilst cars are already banned on Oxford Street during the day, it is a major thoroughfare for buses and taxis, and is also Europe’s busiest shopping street. It is amongst the most polluted roads in London, with NO2 concentrations around three to four times the legal and healthy limit.

However, whilst pedestrianisation is hugely symbolic, it is not clear that it is the best or only solution. Closing Oxford Street will mean that all buses and taxis are diverted onto nearby roads, displacing the problems of air pollution and congestion elsewhere. The Deputy Leader of Westminster City Council has described this as a “major problem”.

An alternative, as recommended in our report, would be to designate Oxford Street as one of a number of ‘clean bus corridors’ – a proposal which the Mayor supports. Under this model, only the cleanest buses would be used on Oxford Street (e.g. Euro VI hybrid, electric or hydrogen). TfL’s own research shows that Euro VI buses are capable of achieving a 98% reduction in NOx emissions compared to Euro V buses. Hybrids could also switch to electric only mode in the most polluted and busiest areas – a concept known as ‘geofencing’.

If further emission reductions are required, then TfL could also target the taxis using Oxford Street. Again, our report makes a number of recommendations, such as reducing the age limit for taxis, encouraging LPG conversion of the existing taxi fleet, and preventing pre-Euro 6 vehicles registering as Private Hire Vehicles.

Aside from the above, the Mayor has made some further suggestions which we largely support. The Mayor plans to lead by example by upgrading all double-decker buses in central London to be ULEZ-compliant by 2019 (instead of 2020) and retrofitting 3,000 buses used outside central London. The current clean air consultation also makes reference to the Mayor’s proposals for a diesel scrappage scheme, changes to (or devolution of) Vehicle Excise Duty, and a boiler scrappage scheme – all of which are in line with our previous recommendations. We would also urge the Mayor to consider a number of other key recommendations from our analysis, namely:

- GLA / TfL to create a loan scheme or financing solution for LPG conversion of taxis

- Reducing the age limit for taxis from 15 years to 10 years (with an exemption for taxis converted to LPG)

- Amending Private Hire Vehicle regulations to prevent pre Euro 6 vehicles registering as PHVs

- Creating additional freight consolidation centres to reduce freight traffic

- Revise London’s boiler emission standards and Air Quality Neutral policy

- Consider the potential conflict between the GLA’s decentralised energy target (which is encouraging the deployment of Combined Heat and Power boilers and biomass, amongst other things) and London’s air quality plans.

In summary, we applaud the Mayor’s ambition to tackle air pollution in London, but it needs to be done in a measured way, based on the best available evidence, and in a way which does not unduly penalise businesses and residents. That way the Mayor’s plans are more likely to gain approval, and ultimately be more successful in the long run.