This morning’s newspapers are filled with the story that Volvo is to go ‘all electric’ from 2019. Volvo announced yesterday that from 2019 it will no longer sell any cars that only have a petrol or diesel engine, and will focus instead on a new range of Battery Electric Vehicles, Plug-in Hybrids, and so-called ‘mild hybrids’.

Alongside this comes the news that France is to ban the sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2040, and predictions from analysts Bloomberg New Energy Finance that electric vehicles will make up the majority of new car sales globally, from 2040.

Does this signal ‘the death knell’ for diesels, the ‘end of the road’ for the combustion engine, and the ‘historic end’ of gas guzzlers?

Well, yes and no…

Will we really see the back of the combustion engine? And are electric cars clean?

Beyond the hype, it is worth clarifying first that Volvo will in fact continue to sell cars with a combustion engine, and cars that produce greenhouse gas emissions.

‘Mild hybrids’ are cars with a smallish battery and electric motor which are capable of powering the vehicle over short distances and/or providing a temporary boost alongside the engine. In this case the battery is charged solely by the internal combustion engine, which means that mild hybrids still use petrol or diesel as their only fuel. Hybridisation of this sort is an important step forward in technology development, but is largely about improving the efficiency of fossil fuel use.

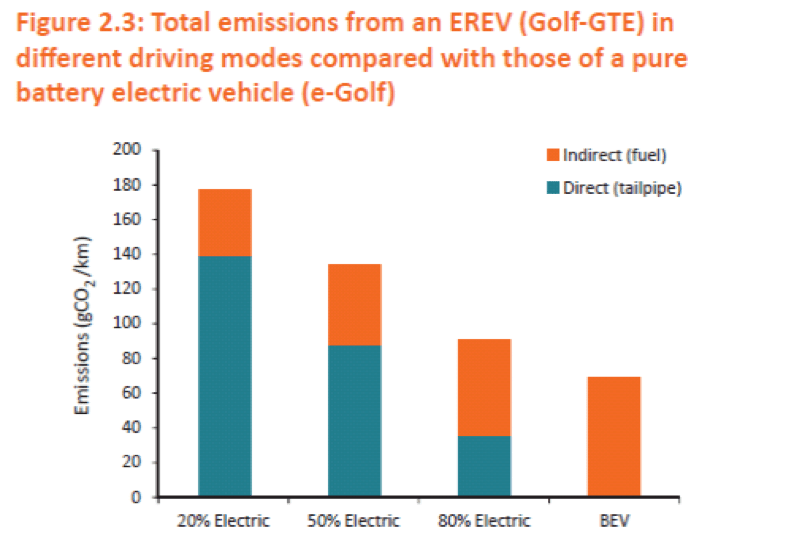

Plug in Hybrids (or ‘PHEVs’) are a further step towards full electrification. PHEVs have a conventional engine combined with a battery and motor, but in this case the battery can be charged from the mains as well as from the combustion engine. From an emissions perspective, PHEVs should in principle be cleaner than conventional vehicles. However, as discussed in our recent report, Driving Down Emissions, in practice the relative emissions from PHEVs vary considerably depending on usage patterns (i.e. whether they are used mainly for short or long journeys), the size of the battery, and how often they are charged. If PHEVs are charged rarely and used mainly for longer journeys, then they may be no better than conventional vehicles in terms of efficiency or emissions (in fact they can be worse). Manufacturers’ claims that PHEVs can achieve efficiencies of 150 miles per gallon or more are highly misleading and reflect the quirks and deficiencies of the European vehicle testing regime.

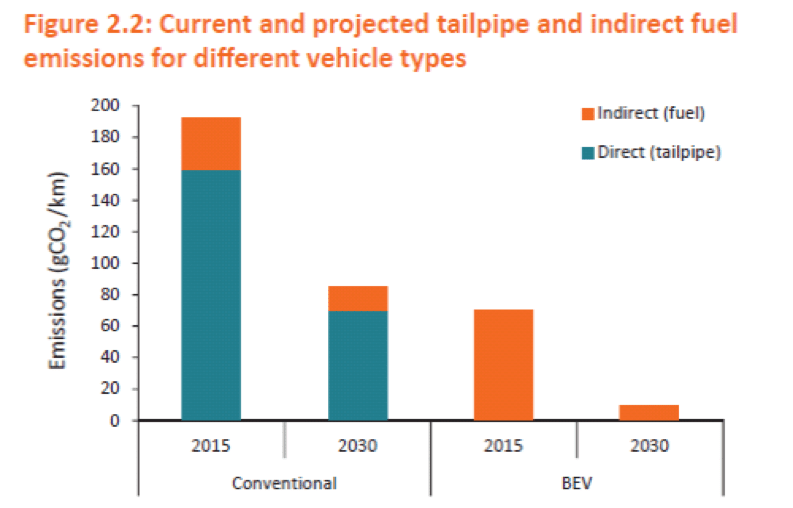

On the other hand, Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) already have much lower emissions than conventional cars. One of the criticisms levelled at BEVs is that the emissions are simply moved from the tailpipe to the power station. Whilst this is true to an extent, the ‘indirect’ emissions associated with the power used in a BEV are lower than the direct tailpipe emissions in a conventional car (assuming GB grid carbon intensity). This difference will only increase as the power system is decarbonised.

When will we see mass adoption?

The second thing to consider is how quickly we are likely to see mass adoption of electric cars. Will they quickly become the default option? And how long will it take before the majority of cars are electric?

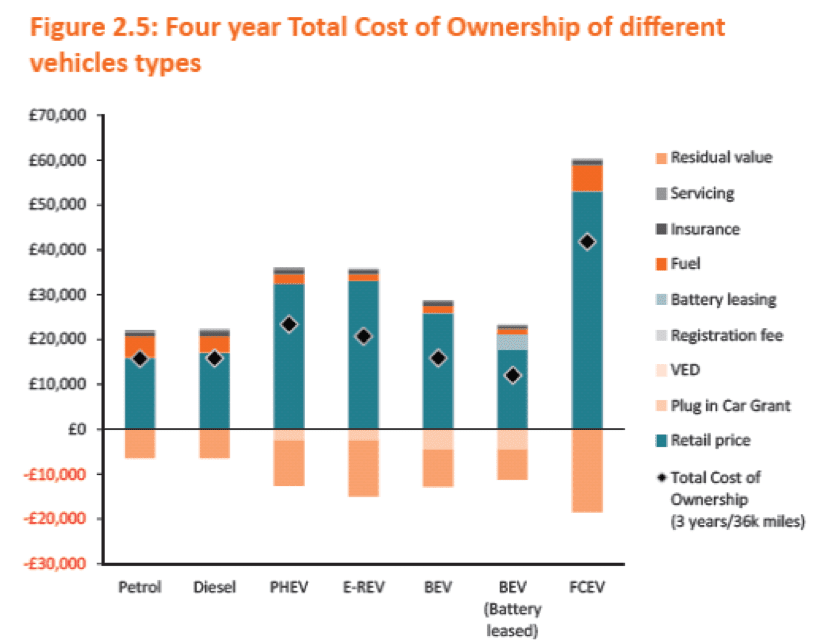

Here the signs are promising, although there is still some way to go. The cost data in our report suggests that BEVs (cars) are already cheaper to buy and run than conventional cars, based on the four year cost of ownership. The same is true of larger cars and small vans. However this is in part due to the fact that they are eligible for significant grants from the Government (e.g. £4,500 per electric car).

Looking forward, BEVs and PHEVs are expected to become cost-competitive with conventional cars without grants by the early 2020s. Indeed, in our report we suggest that the Government should signal a phase out of grants for BEVs and PHEVs by the early 2020s to avoid over-subsidising the technology.

That said, even once new electric cars become cost-competitive, it will take time for this to filter out through the fleet. The average age of the UK car fleet is around 8 years, and many cars last for 15 years or more. Even if electric cars made up the majority of sales by say 2025, they would be are unlikely to make up the majority of cars on the road until well into the 2030s.

What about trucks and buses?

Whilst electric is quickly becoming a viable and affordable option for cars and small vans, the same cannot yet be said about larger vans, trucks and buses. Although there are a small number of single decker electric buses on the road (e.g. in London) the technology remains at an early stage. It will be difficult to apply battery-only technology to double decker buses and HGVs – due to the huge batteries that would be required, and the long charging time.

For this reason, technology developers are also looking at alternatives such as hydrogen fuel cells – which have a far greater energy density than electric batteries. For example, one company is looking to develop a hydrogen powered HGV that could travel 1,200 miles without refuelling. As discussed in our report, the difficulty with moving to hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is how to produce, transport and distribute large volumes of low carbon hydrogen.

Another alternative is to move to natural gas as a vehicle fuel. Vehicles running on Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) or Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) are common in the US and Europe, but relatively uncommon in the UK, despite the existing network of 1,400 LPG refuelling stations. LPG and CNG can deliver a significant reduction in local air pollutants (NOx and particulates) but offer little or no savings in greenhouse gas emissions (unless the gas is produced from wastes or renewable sources to produce biomethane).

‘I’m afraid to tell you there’s no money left’

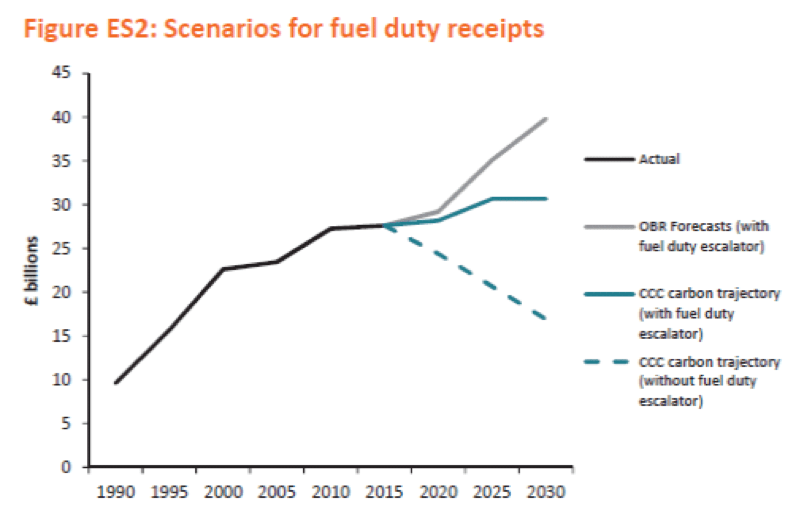

One final thing to consider is the fiscal impact of shifting from petrol and diesel to electric or other low carbon vehicles. The Government currently raises around £28 billion through fuel duties on petrol and diesel. The latest long-term forecasts from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility assume that this will increase to around £40 billion by 2030.

However, as we move from conventional vehicles to low carbon alternatives, fuel duty receipts could be at risk. Policy Exchange analysis shows that if we achieve the carbon trajectory suggested by the Committee on Climate Change, fuel duty receipts would actually be between £17 billion and £31 billion in 2030 – or £9-23 billion lower than the OBR is suggesting. In fact, our analysis suggests that without policy changes, by the 2030s the total tax take from road use could be less than the cost of running the road network. The Government has seemingly failed to recognise the pace and extent of this change. In the future, the Government may need to consider shifting the balance of road taxes from fuel duties towards road user pricing models such as tolls, congestion charging zones, or ‘pay per mile’.