Now that the dust is beginning to settle following the historic Paris agreement last weekend, policymakers will be returning to the day-job of how to put it all into practice. Paris has delivered a hugely ambitious agreement to limit the increase in global temperatures to “well below 2°c” and to drive efforts to achieve 1.5°c. However, a very sizeable gap remains between that ambition and the emissions pledges made by individual countries, which are projected to result in warming of 2.7°c. For the ambition to be achieved, countries will not only need to deliver against their emissions commitments, but ratchet them up over time.

In a UK context, this means delivering against the carbon budgets, which set the UK on a path towards a largely decarbonised economy. Based on current policies, the UK is on course to deliver and exceed the 2nd and 3rd carbon budgets to 2022. But DECC projections show there is a significant gap to achieving the 4th carbon budget, as well as the 5th carbon budget recently proposed by the Committee on Climate Change (see chart). Moreover, the CCC has already said it will look at whether the ambition of the Paris agreement means that “further steps will need to be taken” domestically.

The End of Unabated Coal

One of the areas of focus for DECC in the coming months will be how to deliver a phase out of unabated coal by 2025, as announced in Amber Rudd’s “reset” speech. This was a hugely symbolic commitment for the UK going into the Paris negotiations. The UK is now one of a growing number of countries reconsidering coal: the Netherlands has also announced a coal phase out, in the United States over 40% of coal plants have already been shut down, and we may have already seen peak coal usage in China. A UK coal phase out would achieve a huge reduction in CO2 emissions over the next decade, not to mention the health benefits associated with reducing local pollutants. As it stands there is 17.7GW of coal capacity on the GB power system, which was responsible for 68% of power sector emissions in 2014.

Following the reset speech a month or so ago, Policy Exchange held a roundtable of energy experts to debate the policy options to achieve a coal closure, as well as the implications in terms of cost, security of supply, and the generation mix.

A starting point for the discussion was around the timing and impact of the proposal to end unabated coal. It was argued that a significant proportion of coal capacity is likely to come off the system anyway in the coming years, due to European environmental regulations such as the Large Combustion Plant Directive and Industrial Emissions Directive. Coal power stations at Longannet, Eggborough and Ferrybridge will all close by March 2016, representing a total of 5.2GW of capacity.

Through the first two Capacity Mechanism auctions Government has contracted much of the remaining coal capacity to remain on the system until 2018-2020 (the only exception being Rugeley, which has failed in both auctions to date). The outcomes for 2020 onwards will not be determined until the 2016 auction.

| Capacity (MW) | 2018-19 delivery | 2019-20 delivery | 2020-21 delivery | |

| Drax | 1280 | 1 Year contract | 1 Year contract | Bid in 2016 |

| Ratcliffe | 2060 | 1 Year contract | 1 Year contract | Bid in 2016 |

| Aberthaw | 1692 | 1 Year contract | 1 Year contract | Bid in 2016 |

| West Burton | 2000 | 3 year contract (3 of 4 units) | ||

| Cottam | 2000 | 3 year contract | ||

| Fiddlers Ferry | 1961 | 1 Year contract (3 of 4 units) | No contract | Bid in 2016 |

| Rugeley | 1026 | No contract | No contract | Bid in 2016 |

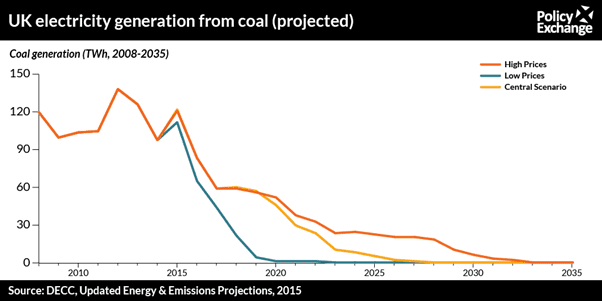

However, beyond that DECC’s latest projections show a wide band of uncertainty, with a coal phase out occurring some time between 2020 and the early 2030s (n.b. the projections do not factor in the coal closure announcement). The commitment to end unabated coal by 2025 could therefore be significant, even if it serves only as a backstop policy.

There are a number of policy options available to remove coal from the system. It could in theory be achieved through carbon pricing alone (e.g. reinstating the carbon price floor escalator), but this could be very costly, making the UK uncompetitive compared to the rest of Europe. The more straightforward alternative is simply to regulate the outcome through an Emissions Performance Standard (EPS). The UK already has an EPS which applies to new power stations, but DECC could amend it to include existing generators. There are a number of design choices – for example whether this is an “instantaneous” standard in the form grams of CO2 per KWh, or a “bubble” standard in the form of total emissions per MW, and whether a certain number of running hours are permitted above the standard. From a system security point of view it is preferable for a gradual phase out rather than a cliff-edge, which suggests that an instantaneous standard should be avoided. DECC is expected to consult on detailed policy design in the New Year. Whatever policy is taken forward in this area, it will also be important to consider how this interacts with existing legislation such as the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED). Companies have until the 31st December 2015 to decide whether to opt in and comply with the IED, or opt out subject to limited running hours. The commitment to end coal altogether by 2025 will clearly impact on investment and operational decisions.

Aurora Energy Research, an energy market modelling and advisory firm, has produced analysis estimating the impact an accelerated coal closure could have. They expect that the policy would add around £2 per year to the average household energy bill (on average between now and 2025). From a security of supply point of view, the power system could cope with coal closures by 2025 or even earlier assuming the Capacity Mechanism is sufficiently robust to ensure new build projects winning capacity contracts to fill the gap left by coal are delivered on time.

However, there remains a risk that coal power stations now close earlier than expected – which whilst positive from an emissions point of view, could be damaging from a system security point of view. It will be important for Government to signal any policy changes in time such that the Capacity Mechanism can react.

There are also questions in terms of what will fill the void as the remaining coal stations come off the system. Amber Rudd’s “reset” speech made a clear case for gas and nuclear power stations to fill the void. However, nuclear is unlikely to deliver new capacity until at least 2025, and the recent Capacity Mechanism auction delivered anything but gas capacity, clearing below the point at which new gas power stations are viable. In fact the only new capacity in the auction was 1GW of diesel/peaking plant, and 0.5GW of Demand Side Response.

Aurora’s modelling suggests that coal closures would result in new gas power stations being built earlier in the 2020s than they otherwise would be. But a bigger contribution to filling the gap left by coal would come from existing gas power stations running more hours and having lifetime extensions, rather than closing.

Whilst this may be a solution in the medium term, questions remain in terms of the use of gas long term – particularly given the setbacks to the UK pursuing Carbon Capture and Storage, which now makes gas with CCS a distant prospect. Whilst a coal to gas switch would bring about significant decarbonisation, it is important to consider the compatibility of this with future carbon budgets in the late 2020s, which as shown above will be challenging to meet.

Therefore, an alternative would be to seek to replace coal with a mix of alternatives, including some gas capacity combined with interconnectors, Demand Side Response, storage, and renewables. Aurora’s modelling suggests that this would be no more expensive, and could even be cheaper, than predominantly gas generation, and still maintain reliability.

Overall, the commitment to end unabated coal remains hugely significant, delivering significant decarbonisation for relatively little cost. But the challenge of maintaining security of supply whilst the whole coal fleet retires from the system should not be underestimated, and DECC will now need to work through the detailed policy design.