Air Marshal Edward Stringer (Ret’d) CB CBE

Senior Fellow

At a recent event at Policy Exchange the Prime Minister of Estonia, Kaja Kallas, made an eloquent, well-argued and ultimately moral speech on the necessity to stand up to Putin and deny his aggression and his war crimes in Ukraine any legitimising veneer. For all our futures, it was necessary for Russia to be defeated in its aims in Ukraine. She reminded the audience that Ukraine needed help to resource its fight, and that help must be constant must endure.

This certainly chimes with what has been, to date, a steadfast commitment from the Northern and Eastern European nation-states to see Ukraine prevail in the war. But is that mirrored elsewhere in Europe? Or are we beginning to see a divergence in approach? Does this matter if the wider ‘Western’ coalition broadly holds?

Staying power, and holding one’s nerve, has been important in every conflict in which I have participated, from Gulf War1 through Kosovo to Libya. At some point in every one of those conflicts, commentators have wobbled, questioning anxiously whether we have become bogged down in ‘a quagmire’. There are almost always suggestions that a ceasefire should now be pursued — and there are always moral grounds why such should be sought. News outlets are always looking for reverses in fortune to report, and an angle, and so will amplify such sentiments. However, it is surprising how many people in the military can be seduced by the idea of a lightning victory, the success of shock and awe, and so be surprised and shocked when it doesn’t materialise. Yet, while decisive single battles or swift campaigns — Cannae moments — remain the acme of generalship, they are extremely rare.

The reality is that even if a tactical battle looks evenly matched, behind the frontline each side is recuperating to prevail in the long war, and one side will be doing it smarter and better than the other. Our own history provides good examples in the Battle of Britain (one could also use the Battle of the Atlantic), where it looked touch and go through August into September 1940. Despite its losses, the Luftwaffe appearing able to launch wave after wave of bombers with ‘The Few’ of the RAF grimly hanging in there.

Recent scholarship reveals it was not nearly as close run as the myth suggests. Throughout the battle, Britain was producing more aircraft and pilots, it was rotating squadrons through frontline tours to allow them to recuperate and gain experience, and all the while it was learning and adapting. In contrast, the Luftwaffe was steadily eroding its men and materiel in a series of ‘one last heaves’. The RAF got steadily stronger throughout the battle and in September the Luftwaffe was forced to give up the fight. No individual battle was decisive, the frontline on the ground moved not one inch, but relative national power was revealed. The result was strategically important for the course of the war. Will to win was reinforced at home: abroad, allies stuck with the UK.

Is this what is going on in Ukraine? After a failed lightning campaign to take Kyiv, defeated by Ukraine’s more nimble tactics, Russia has now concentrated its forces in the Donbas. It is executing a grinding campaign of attrition, using incremental, pinch-and-hold tactics that rely on heavy concentrations of artillery, ‘dumb’ air power, and much destruction. Ukraine’s losses are piling up in the attritional fight, and the frontline on the ground is not moving very much. Russia may be opting for ‘winning ugly’, but could it, as many commentators suggest, be winning nevertheless?

The honest answer is that we do not know, but Ukrainian leaders have been open in admitting that the fighting has become much more severe, that they are taking greater losses, and that they need support. The Russians may have picked a battle that appears to play to their strengths, but not everything is set in their favour. It is clear that the Ukrainian population is motivated and has a strong will to fight. Russia has to expend effort pacifying and then governing the territory it has taken. This takes a huge number of troops even with a semi-compliant population, and Ukraine has a history of breeding partisans.

Attacking forces tend to suffer heavy casualties, even when well organised. It is clear that Russian forces are not well led, trained or motivated, and have taken significant casualties in the Donbas. Russia doesn’t publish its casualties, but its Donetsk militia does; if Russian forces fighting alongside the militia mirror their casualties, then somewhere around 55% of its original force has already been lost. This is unsustainable, even before Russia’s poor capacity to recuperate is factored in. On top of that, recent assessments from Western defence officials suggest that even Russia cannot sustain the rate it is using its artillery. So, both sides are suffering significant attrition that is likely unsustainable. The key questions are: who can sustain the longest, and how does it do so better than the enemy?

The foundational myth of 1940, of which the Battle of Britain is a key part, is ‘Britain Alone’. But military economists have now debunked this too. Britain’s Empire and network of allies, with the Royal Navy to secure its sea lines of communication, gave it greater access to resources than Nazi Germany could muster. This is the formula that Ukraine must now rely on in its hour of need as it fights its own existential battle of attrition.

Ukraine has no Empire to resource it as Britain did in 1940, but it does have allies. Nominally that is the entire ‘Western’ bloc of developed, democratic nations. It is the overlap of the G7, the EU and NATO. NATO’s annual defence spend is $1.2tr, or 250 times more than Ukraine’s budget of $5bn. Russia’s is $66bn.

Put simply, the combined economic and industrial capacity of Ukraine’s allies dwarfs Russia’s. To which one can add the crippling effect of unprecedented sanctions that, inter alia, deny it the high-end components that are essential to make advanced weapons systems. The West has an arsenal and foundry that, if employed properly in the service of Ukraine, should allow Ukraine’s armed forces to recuperate from the attrition in a much better state than Russia.

But there is another vital facet that must be considered too. Beyond the ‘physical’ component of fighting materiel, and the ‘moral’ component of the collective national will to fight, there is the ‘conceptual’ component. In essence, this is the ‘how we will fight’ component. For example, in the Battle of Britain the use of Radar, an innovative, networked command and control system using many civilian components including the GPO, a mobilised civilian industrial base, and a better intelligence system, meant the Luftwaffe was out-thought as well as out-fought. This is the battle of force development, adapting and fighting smarter such that you get ‘the other guy to die for his country’.

This systemic thinking needs to be fully applied to assist Ukraine, which has already shown in its imaginative defence of Kyiv and use of its small air force that it is used to thinking creatively. Radar might be a direct read across — but in this case it is the location-finding radars that track artillery shells and plot their trajectories to locate the guns firing at you and allow very accurate counter-battery fire to destroy those guns (if they are not moved in short order after firing a barrage).

In this duel of artillery, a resilient network to link myriad sensors (including novel use of drones and electronic warfare) to gun batteries, longer-range guns that can hit without being vulnerable to return fire, and inexhaustible supplies of ammunition are the vital attributes. Given them, Ukraine can prevail in the battle of attrition. The exact position of a barely moving front line is not the important metric here. Ukraine needs to make the Donbas unbearable for Russia’s army.

The West can provide Ukraine with all these. But important decisions need to be made over the nature of ammunition: to stay with the ex-Soviet 152mm ammunition, or transfer Ukraine onto NATO 155mm standard guns and ammunition, or try and run a logistics system that caters for both? This decision will hinge on the ability to sustain usage rates in shells — which will almost certainly require us to put some factories on a war-footing. This will be an indicator of the West’s collective will to support Ukraine in the long term.

Which brings us back to Prime Minister Kallas and her determined support for Ukraine. It is typical of the dynamic support and moral clarity being shown by the Baltic and East European elements of the Western bloc. They have lived under totalitarian and thuggish Russian rule, understand what it means, and are sure they don’t want it. They are also intimately aware of just how threadbare is the Russian Bear across the border. They understand that the supposed military superpower is also a sclerotic kleptocracy where corruption rules and very little works, and strength in depth is a chimera. They know Russia can be beaten and believe that it is firmly in the West’s interests that it is beaten, thereby greatly diminishing the major military threat to NATO, one that is made manifest on their borders. Allow Putin to win in Ukraine and emerge enhanced and we will all be paying appropriately high defence premiums for decades.

In contrast, the centuries old strategic culture of the Old Europe appears more wedded to an atavistic view of the inevitability of Russian might and power. The respective histories of France and Germany have led French and German strategic culture to regard Russia as a perpetual player that it benefits them to deal with, and with a modicum of due deference. Hence, despite some strong words from Élysée staffers, Macron’s personal and repeated plea not to see Russia humiliated, and his regular telephone calls to Putin; in Germany, Scholz — schooled by Ostpolitikers — saying that Ukraine mustn’t lose, but not that Russia therefore must lose. At the very least, these mental gymnastics reveal a belief in some third way resolution that sees a graceful climbdown and a return to the status quo ante. And, who knows, cheap gas again.

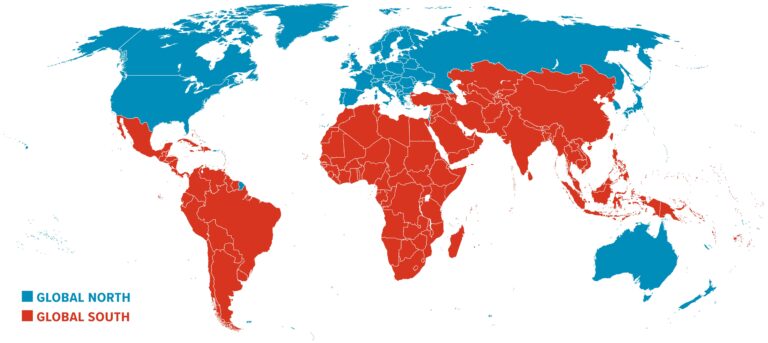

After all, led by Germany, much of Europe has still been buying Russian gas, and at a rate that equates to paying Russia 150% of its current defence budget. Consistent support of allies is vitally important, but behind Old Europe’s rhetoric the reality of its actions means that it is in effect funding Russia’s war to a greater extent than Ukraine’s. No wonder the emerging powers of the Global South are confused when we ask them for moral clarity and to take sides.

And what do Putin’s inner circle of Siloviki make of the disconnect between the Old West’s rhetoric and the reality of its actions? Might they take some comfort from this? No wonder that — when looking at the same evidence — the smaller states of Northern and Eastern Europe, who have the most serious security concerns, are getting exasperated. Hence Prime Minister Kaja Kallas’ recent commentary that opened this piece — most pithily summed up in her exhortation to fellow European leaders: ‘If you really want Putin to get the message that he’s isolated, don’t call him!’ They see more clearly than Old Europe the strategic inconsistencies and seams in the Western position and know Putin is adept at exploiting these. They also know they will be next on his list if he is allowed to recover.

The evidence seems to support them. Blood curdling Russian threats have dissolved to insouciant shrugs when ignored. Finland and Sweden joining NATO? Nuclear weapons were brandished in the build-up to an announcement, then membership was dismissed as ‘no big deal’ when it became a fait accompli. Eastern Europeans instinctively understand that Putin’s behaviour follows his favourite Lenin quote: ‘Probe with the bayonet, if you find mush keep on pushing, if you hit steel, pull back.’ They sense it is time to reveal steel, not mush.

Above all, they have believed for some time that which has now been revealed, and which they fear Old Europe has not fully acknowledged — there can be no deal with Putin as he is untrustworthy. A peace deal will not guarantee peace but may grant the aggressor spoils. He will come back for more as he will have sensed weakness. That is a poor strategic outcome that emboldens aggressive authoritarians everywhere.

There are, of course, myriad complexities and inconsistencies in such a complex picture. Realists will use these to explain why most options are too difficult and doomed. But inaction has costs too, and if one stalls long enough then that procrastination is itself an action. Fears become self-fulfilling prophesies: Russia creeps forward and learned helplessness consumes us. Less often considered is the moral and legal dubiousness of this half-way house. Is providing some weaponry to Ukraine but giving financial succour to Russia not one way of prolonging the terrible consequences of war (including global food shortages), which is counter to International Humanitarian Law? Indecision is a poor option, and we should make some statements of what we really believe and want.

Some conclusions:

Russia is not the military superpower the Old West has assumed it to be and may not be able to sustain a war of attrition and occupation in Ukraine.

Russia should no longer be genuflected to; it is now revealed as a pariah state that cannot be bargained with and has far less strength in depth — economic, demographic, military, social — than previously assumed.

Russian threats to NATO have been hollow and Putin does not want to provoke the West.

It is in the West’s strategic interests that Russia is humbled in Ukraine and emerges unable to realistically threaten its neighbours.

Ukraine has the wherewithal to defeat Russia’s invasion if it can rely on the West to be the engine of recuperation and force-development that gives it a winning position in the war of attrition.

Mixed messaging from the West is likely to encourage Russia to persist, and third-party powers to continue to hedge.

Therefore:

The West should arrange itself deliberately as the supporter of Ukrainian military capacity.

If it does, then Ukraine should be able to defeat Putin’s intent for his invasion and negotiate terms for ending the conflict that are acceptable to Ukraine and leave Russia militarily and economically exhausted.

If this happens global order is enhanced and the West can concentrate on addressing the main threats of climate change and Chinese authoritarianism.

If the opposite happens, then we waste future resource for decades in defending against a Russian threat we did not need to see recover. China learns the right tactical lessons from Ukraine and the wrong strategic one. And we have little left in the locker to deal with climate change, food shortages and energy security.

There is a lot at stake.

Air Marshal Edward Stringer (Ret’d) CB, CBE is a Senior Fellow at Policy Exchange. He is a former Director-General Joint-Force Development / Defence Academy and a former Asst. Chief of the Defence Staff (Operations).