Authors

Content

-

- The Regulatory Environment

- The Regulatory Bodies

- The Purpose of Solvency II

- The Risk Margin

- Government Risk Margin Proposals

- Matching Adjustment and the Fundamental Spread

- Risk Margin and Matching Adjustment Reform Potentially At Cross-Purposes

- Rating Productive Assets

- Regulatory Uncertainty

- Eligibility for the Matching Adjustment

- Using the Prudent Person Principle

- The Chicken and Egg Problem

- Not Missing a March: Solvency Capital Requirements

- Regulatory Perspectives

- Ensuring A Regulatory Shift

- Competing Objectives: Experiences from Other Jurisdictions

- Separating Growth from International Competitiveness

- Powers of Review

- More Ambition Needed: Reform of the Charge Cap

-

- Introduction

- The Defined Contribution Pension Market in the UK

- The Structure of the UK Pension Market

- Australian Superannuation

- Value for Money

- Investing in Alternative Assets

- How Australia Consolidated

- Recent Changes

- Current Plans in the United Kingdom

- Master Trusts

- Where the Financial Services and Markets Bill Can Help

- Better Public Sector Pensions

- Improving the Local Government Pension Scheme

- Solvency and Performance of Canadian Schemes compared to the LGPS

- Making Structural Change

- The Dutch Approach

- Managing Civil Service Pensions and Boosting Investment

- The Opportunity

- Exploring the Case for Funded Pensions in the UK

Foreword

Tony Danker

Director General of the Confederation of British Industry

These are tough times for business leaders. The headwinds – rising inflation and energy costs, a tight labour market, the bleak economic outlook – are many. And, in these fiscally constrained times, Government’s ability to create tailwinds is limited too.

That said, there are opportunities – there are always opportunities – if you know where to find them. Unleashing Capital identifies some of the barriers to businesses and pinpoints low- or no-cost ways to sow the seeds for growth. It’s a measured, evidence-based list of practical steps that policymakers and political leaders can take to create long-term prosperity.

Many of the recommendations reflect the asks of businesses within CBI membership. They want to see greater collaboration between national and local institutions, a simplification of ways of working. They would prefer an outcome-based approach to regulation. And they’d also like to see regulatory reform where existing rules stifle innovation.

The businesses I represent are demanding stability – both political and economic stability. They’re doing so because that is the precursor to growth. Without confidence in the UK and an understanding of the UK’s plan for growth, investors will simply wait and see before investing. And right now, we don’t have that time to spare.

Unleashing Capital presents some practical and highly relevant ideas – ideas that should challenge Government and policymakers to think about growth differently. It’s this kind of radical thinking that can help shake the UK out of its low-growth state and kick-start the next wave of investment, prosperity and productivity.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

The United Kingdom is one of the world’s leading financial centres. Pension wealth in the UK is £3.4 trillion, the second largest in the world after the United States. The UK’s asset management industry is the largest in Europe. The UK’s insurance investments are the second largest in Europe.

Yet despite these inherent advantages, UK institutional investors do not invest proportionately in the kinds of assets that spur economic growth and create long-term prosperity. UK pension funds and insurers are less likely to invest in infrastructure, private equity, venture capital and private credit than their international counterparts.

This contributes in part to the UK’s weaker economic performance. UK cities are less productive. UK infrastructure is less competitive. UK venture capital is growing more slowly. UK firms find it hard to scale-up, for lack of long-term funding options.

UK pensions allocate 7% of their assets to alternatives – such as property, private equity and infrastructure. The average amongst the countries with the largest pension markets, the ‘P7’1The ‘P7’ is comprised of Australia, Canada, Japan, Netherlands, Switzerland, UK, US is 19%. If the UK increase its allocation in these alternatives to the P7 average, and just 10% of that amount was invested in the UK, this would in theory release £40.6 billion for UK investments in private equity, infrastructure and property.

In terms of the insurance investments, the UK allocates significantly less, proportionately, than Germany, France, Italy and Spain. In terms of investing in infrastructure funds, private equity funds, real estate funds, and property, UK insurers come second last out of the 10 largest European markets. If the UK invested in infrastructure at the same scale as France, there would be £10.2 billion more for infrastructure funds, £13.2 billion more investment in private equity funds and, overall, an additional £71.6 billion invested in alternatives and property. These may seem like large numbers, but the actual shifts in terms of overall investment proportions are very small. For example, to invest like France in infrastructure funds, UK insurers would have to shift their exposures less than half of a percentage point. This is not fundamentally radical, but it would have significant consequences.

To be clear, this report is not suggesting that the Government can direct institutional investors to invest in particular assets. Far from it. Pension funds and insurers have responsibilities to their policyholders and their pension scheme members, and they must generate the proper returns and protection for their clients. However, this report identifies key ways in which the regulatory and market environment hinder investment in a wider range of assets that are available to international insurers and pension funds. These regulatory burdens are complex; for instance, all EU markets are subject to Solvency II, and yet EU insurers tend to invest more in alternatives, thanks to specific ways Solvency II is applied in different jurisdictions. Reforming Solvency II in the UK is not just about developing tailor-made rules in London but ensuring that the UK regulators are doing so in a way that promotes growth and diversity.

This report aims to tackle the complexity of these issues head on, to mobilise investment across the UK. It makes recommendations in four areas:

- The Regulatory Environment

- The Structure of Pension Markets

- The Role of Local Government

- The Role National Institutions

Some of the recommendations this report makes are technical, and some are strategic; many involve an element of both perspectives. This may appear incongruous, but it is a demonstration of how difficult and complex the problem of mobilising capital in the UK is. Better national institutions could potentially create more projects of investment, but if the regulatory environment does not change, this will make little difference. Conversely, improving the regulatory space will only get you so far if national and local institutions are not able to promote and create greater investment opportunities.

To underline the point again, this report is not suggesting that these changes can happen overnight. Pension funds and insurers have vital responsibilities to ensure that they meet their liabilities, those factors must be paramount. Rather, the argument set out here suggests simply that the current regulatory environment and market structures are not optimal, and that genuine improvements can be made to how the Government regulates and how markets operate.

To balance the broad analysis with implementable policies, this report is structured around four key strategic priorities for Government, under which sit 20 recommendations. The strategic priorities are as follows:

Strategic Priority 1: Creating A Better Regulatory Environment

Government should prioritise a regulatory environment for the financial sector that encourages diversification, policy holder returns, and balances policyholder protection and financial stability with competitiveness and growth. Recommendations that will help fulfil this strategic priority include

- Ensuring that growth and competitiveness are properly balanced against other statutory objectives, by making growth a primary objective and ensuring that the regulators publish an explicit document on how the secondary international competitiveness and competition objectives are to be balanced

- Reforming Solvency II insurance regulation in a way that facilitates significant investment from the sector, by making the right reforms to the Fundamental Spread, Matching Adjustment, and Solvency Capital Requirements

- Developing the regulatory investment framework for insurers, the Prudent Person Principle, to increase transparency and be more accommodating for alternative, growth-supporting assets.

- Ensuring that a regular review cycle of rules is created to ensure that genuine reviews can occur without the spectre of Government interference

- Reforming the pension charge cap, and in particular to ensure that reform excludes the fixed element of carried interest

Strategic Priority 2: Making A Better Pension Market

Government should prioritise reforming and consolidating the pension market. The UK should look to international comparators, such as the Netherlands, Canada and Australia to find examples of strong pension markets that invest in alternative assets and contribute to economic growth. Recommendations that will help fulfil this strategic priority include:

- Launching a consultation in regard to reducing barriers to consolidation in the pension market, and proposing expanded powers and remit for the current value for money test

- Using the ‘have regard’ powers in the Financial Services and Markets Bill to ensure regulators consider the impact of regulations on the prospects for consolidation

- Consolidating the current LGPS structure to reflect international best practice, as shown in the Canadian and Dutch public sector pension models

- Issue a call for evidence on shifting to a funded model of public sector pensions

Strategic Priority 3: Empowering Stronger Local Government

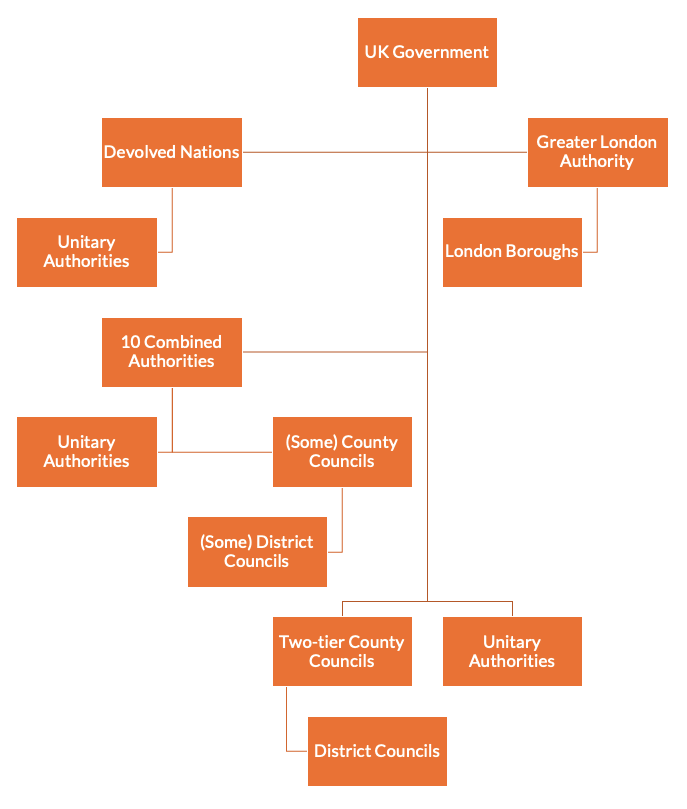

Local Government in the UK is fragmented and weak compared to its international peers. Government should look to devolve powers to local communities that reduce political risk and increase the ability of local communities to fund local projects with their own resources. Recommendations that will help fulfil this strategic priority include:

- Being more ambitious in developing devolution deals, aiming to expand existing combined authorities and ensuring new combined authorities cover large, economically viable areas.

- Devolving the full suite of strategic planning powers to combined authorities, including the creation of statutory spatial frameworks and Levelling Up Innovation Zones.

- Fully devolving business rates to combined authorities, including the power to re-design valuations, change multipliers, and set reliefs according to local needs, and embracing multi-year funding settlements.

- Use the LIFTS model to develop similar investment vehicles for local infrastructure facilities. Ensure that local Mayors can encourage regulatory collaboration and convene national institutions.

Strategic Priority 4: Building More Collaborative National Institutions

National institutions in the UK can be better used to encourage productive investment from institutional investors and create a more collaborative environment. Government should work to ensure that national institutions are as effective as possible in meeting the UK’s investment goals. Recommendations that will help fulfil this strategic priority include

- Finalising plans for the UKIB and publishing its methodology for assessing additionality, so that firms have certainty.

- Developing an MoU between Homes England and the UKIB with a view to a possible merger. Homes England and the UKIB should be encouraged to develop a strong relationship, and Government should review whether these institutions should be merged.

- Using the British Business Bank to better co-ordinate the multitude of different private-sector and public-sector bodies responsible for increasing economic performance and investment in business.

- Foreseeing significant capital investment from Solvency II reform and the FSM Bill, Government should create a UK Institutional Growth Fund to spur growth and create co-investment opportunities with the private sector.

- Leveraging the British Business Bank’s role in increasing access to equity and credit for small and medium-sized firms and increase access to institutional investment. The British Business bank should work with regulators to make more businesses viable investment propositions for institutional investors, and create a bespoke fund to test new regulatory approaches

These recommendations range from big to small, from calls for evidence to technical changes. However, the range of suggestions put forward demonstrate the scale and complexity of the challenge facing the United Kingdom. This report hopes to come to grips with that challenge and spark a conversation on how the UK can seize the opportunities sitting here already. The Government rightly makes much of the need to unleash all the strengths of the UK economy. It will not be able to do this without unleashing capital.

Next chapterIntroduction

The Economic Context

The United Kingdom’s current economic woes are particularly long-term and acute. An OECD projection from late 2021, before the economic shock, predicted that the UK, to 2060, would have a slower GDP per capita growth than the Euro area and the G7. If the GDP growth of the last decade were to be replicated in this decade, the UK would become the poorest country in the Anglosphere by 2028.

Productivity has also suffered. The UK has had the second weakest productivity performance in the G7 between 2009 and 2019.2ONS, International comparisons of UK productivity (IP), final estimates: 2020. 20 January 2022. Link. If UK productivity per hour had kept pace with the previous decade, each worker would be producing £6.62 more per hour worked.3Author’s calculations

Figure 1: Actual vs Trend GDP Per Hour Worked, 2015 PPP, USD

The Importance of Levelling Up

Part of the UK’s economic problem is the unequal growth and productivity experienced by different regions of the UK.

Between 2000 and 2019, London was the only region of England which beat the English growth average. No other major economy only has one region so outperforming.

Figure 2: Regional Growth Rates compared to the England Average, 2000-2019

Furthermore, cities outside of the South East have weaker productivity than they should. The productivity gap between large cities in the UK and other major international economies is larger in the UK than it is in many other economies, like Germany, Japan and Australia.4OECD, Enhancing Productivity in UK Core Cities. 2020. Link. In February 2020, the Centre for Cities found that if the eight largest cities in the UK reached the productivity levels of the Greater South East, the UK economy would be £47.4 billion larger.5Centre for Cities, Why big cities are crucial to ‘levelling up’. February 2020. Link.

In absolute terms, recent analysis shows that the UK is the most inter-regionally unequal country in the OECD with more than 11 million people. At the TL3 level, which is an international standard for measuring smaller regions, the UK is the second most inter-regionally unequal country in the OECD.6McCann, Philip. Perceptions of Regional Inequality and the Geography of Discontent: insights from the UK. 29 November 2018. Link.

Significant investment gaps persist too. Average gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) in the UK per capita was £5,488 in 2020, yet only three regions exceeded the average – London, the South East and the East.7Author’s calculations, using ONS. Experimental regional gross fixed capital formation estimates by asset type. 10 May 2022. Link.

Figure 3: Per Capita Gross Fixed Capital Formation, 2020

ONS8Ibid.

Over the last 15 years, London and the South East have rapidly eclipsed the rest of the UK when it comes to net investment (GFCF) in absolute terms too, as shown by the figure below.

Figure 4: Gross Fixed Capital Formation by Region, Current Prices 1997-2020

ONS9Ibid.

If the three weakest regions alone – Wales, the North East, and the West Midlands – raised their net investment to the national average, this would inject more than £17 billion into the economy. If the North and the Midlands together were brought to the national average, it would increase gross fixed capital formation by £26 billion.

Generating Investment

It would be a mistake, however, to define the challenges in the UK solely as questions relating to the distribution of growth, or one confined to problems in certain regions. The UK economy is not good enough at generating private domestic investment and as such UK growth has not been strong as it could be. If UK GDP per capita growth continues on its current trend since 2008, the UK will be the poorest country in the Anglosphere by 2028.10OECD. GDP Per capita. Constant prices. In 2008, household disposable income was only $1,500 higher in Germany. German households are now more than $7,000 richer.11OECD.

Investment as a percentage of GDP in the UK has been persistently weaker than any other G7 country except Italy since 1980.

Figure 5: Investment as a Percentage of GDP

IMF

British capitalism is becoming less dynamic. The market capitalisation of the top 10 companies in the UK increased from £0.7 to £0.8 trillion between 2000 and 2021, whereas the top 10 US companies increased their capitalisation from £1.5 to £9.1 trillion. In other words, the top 10 companies increased their market capitalisation by 14% in the UK in 21 years, and 507% in the United States.12Lakestar, The UK Financing Gap. June 2022. Link. Since 2010, the London Stock exchange has lost nearly a quarter of its listings.13London Stock Exchange Group. London Stock Exchange: Issuer List Archives 2010-2021. Link. These challenges are compounded by the fact that public markets in the UK have also suffered. The FTSE 100 has underperformed both the US S&P 500 and similar indices in Germany and Japan over the last two decades.14Cheffins, Brian and Reddy, Bobby. Resuscitating the London Stock Exchange. 1 June 2022. University of Oxford, Faculty of Law. Link. Listings on the London Stock Exchange have fallen by nearly a quarter since 2010.

Figure 6: Issuers Listed on the LSE, December

London Stock Exchange Group

Outside of public markets, the UK is also at risk of losing ground in the growth economy. According to OECD data, the UK has experienced only middling growth in venture capital compared to our peers over the last decade. While the UK has started in a strong position, there are competitors coming online.

Figure 7: Venture Capital Total Growth 2010-2021

OECD, Author’s calculations

In European markets, the lack of institutional investment from the UK is palpable. In the latest State of European Tech report, in every year since 2016 except 2019, the UK and Ireland have had less investment dry powder for VC than France and the Benelux countries, and UK pensions provide only 6% of all pension investment into European venture capital.15Atomico, State of European Tech 2021. Link. This at a time when Lakestar, a leading investment fund, has suggested that there is currently a gap of £1.5 trillion in growth financing needed to make UK markets more dynamic and put the UK on a higher growth trajectory.16Lakestart

| Different Kinds of Capital | ||

| Private Equity

Private equity, or unlisted equity, is investment of equity into private companies. Unlike venture capital, these typically are in mature companies, and may involve investing in a firm to execute a restructuring or a different management strategy. Private equity investments are not listed on stock markets, and typically have relatively illiquid structures and longer- term time horizons – such as 10 years. |

Venture Capital

Venture capital is another form of private market funding. Unlike the broader category of private equity the firms in question are new, ‘start-ups’ or relatively small or medium-sized businesses with a relatively high chance of failure, but conversely with strong growth potential. The potential investments are almost never listed. |

Growth Funding (or ‘patient capital’)

Growth capital operates in the intermediate space between venture capital and mature private equity. In the UK, growth capital entities like the Business Growth Fund (BGF) aim to invest in companies that are ready to scale up, but have either not entered public markets, or need long-term capital for growth. Unlike private equity and venture capital where there is, even on a longer time horizon, an immediate look for an exit, growth capital seeks to stay with a company without a definite exit point. |

Growing companies and scaleups are a vital part of the economy. Companies that are scaling up and growing are more profitable, deliver higher wages and are a vital part in closing the gap in economic disparities.17Oxford Economics, The Contribution to the UK Economy of Firms Using Venture Capital and Business Angel Finance, Prepared for the BVCA. April 2017. Link. Yet there are significant funding gaps for these kinds of companies in the UK economy. The Scaleup Institute estimates that, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a structural gap of £5-£10 billion per annum, and a cyclical gap of £7.5 billion per annum.18Scaleup Institute, The Future of Growth Capital. August 2020. Link.

This funding gap also does little for regional policy and growth. Contrary to what may be popular belief, only 33% of growth companies are located in London. 32% are located in the Midlands and North.19Seldon, Sir Anthony and Welton, Stephen. From Survive to Thrive. University of Buckingham and the Business Growth Fund. 2020. Link. A focus on growth capital will help every part of the country.

Tomorrow’s Infrastructure

These funding gaps do not just present in private equity and venture capital either. There remains significant net zero and infrastructure gaps too. The UK Government expects that to 2030, the infrastructure20It is important to highlight too the difference between operating and building infrastructure. Some institutional investors may choose to invest in utilities and other facilities that are already built, others in infrastructure bonds and equity that contribute to the building of infrastructure itself. In both cases, capital helps improve stock and contributes to growth. pipeline will amount to £650 billion. Some estimates put the Net Zero infrastructure needs at £400 billion alone to 2050.21PWC, Unlocking Capital for Net Zero Infrastructure. November 2020. Link. Yet, despite this, the entire UK Investment industry invests only 2.4% of its UK assets in infrastructure22The Investment Association, Investment Management in the UK 2020-2021. September 2021. Link. , a figure unchanged since 2019. Of its total assets under management, the UK invests 0.4% in UK infrastructure.

Here too, the UK needs to catch up to its peers. A 2015 OECD paper noted that the UK’s quality of infrastructure ranked 27th, in the middle of international rankings. The UK invested less than Canada, France and Switzerland and higher than the United States.23Pisu et al, Improving Infrastructure in the United Kingdom. OECD. 6 July 2015. Link. More recently, the Government has identified the need for £650 billion of public and private investment to 2030/31.24Infrastructure and Projects Authority. Analysis of the National Infrastructure and Construction Pipeline 2021. Link. The investment gap on Net Zero assets to 2050 remains. A report by PWC found that the UK had a £400 billion infrastructure gap to 2050. To put that in perspective, in 2019 only £20 billion was invested in all infrastructure by private entities.25PWC, Unlocking Capital for Net Zero Infrastructure. November 2020. Link.

Unlocking Capital

All these economic problems occur despite the fact that the UK has some of the most successful financial markets and largest pools of capital in the world. The UK is one of the world’s largest and most successful financial centres. The international bond markets in the UK are the largest in the world, and assets under management in the UK are the largest in Europe, and the second largest in the world after the United States.26The City of London. The Global City. 2022. Link.

Despite having £3.4 trillion in pension assets, the second largest in the world, UK pensions underinvest in the productive finance that would fund increased infrastructure and provide the long-term capital needed for scale-up businesses. This is not a new problem. As the 1931 Committee on Finance and Industry (colloquially known as the Macmillan Committee) makes clear, underinvestment has been a persistent fact about the UK economy. As the Committee says:

“…speaking generally, the exceptional merits of the City of London lie in the facilities given by the short-term money market for the employment of home and foreign funds; in the financing of trade and commerce, also both home and foreign; and in the issue of foreign bonds, as distinguished from the financing of British industry….the relations between the British financial world and British industry, as distinct from British commerce, have never been so close as between German finance and German industry or between American finance and American industry.”27Committee on Finance and Industry, Report of the Macmillan Committee. C.P. 160 (31). Copy from the National Archives, digitised. 1931. Link.

Fixing the underinvestment problem will also not solve every ill. Global macroeconomic forces are strong, and there are many challenges external to the UK economy that trouble it.

But that does not mean that institutional underinvestment is not important. Across insurance and pensions, more capital could be mobilised, and greater investment could be accessed.

Underinvestment: Pensions

UK pensions notably underinvest in productive assets relative to their international peers, despite the fact that the UK has the second largest pool of pension assets in the world.

Figure 8: Total Assets (USD Billion)

According to the latest asset survey of pensions in the largest pension markets, only 7% of UK pension assets are diverted to other assets, like infrastructure, venture capital and real estate. The average amongst countries with large pension assets is 19%. If the UK could attain that level, with assets worth £3.4 trillion, it would unlock £406 billion for other assets.

Figure 9: Asset Allocation, Pension Funds

An investment injection on this scale likely won’t happen, not least because the share of the UK pension portfolio invested in other assets has actually decreased over the last five years. This is in large part driven by the closure to new applicants for many DB schemes, and and the fact that DB schemes have turned cash-flow negative, meaning they are paying out more than they are taking in in contributions.28Baker, Mark and Adams, John. Approaching the endgame: the future of Defined Benefit pensions in the UK. October 2019. Link.

| Defining ‘Alternative’ |

| ‘Alternative assets’ can mean different things – different estimates can give different results. In the case of this report, some estimates suggest investment in alternatives higher than those suggested by the Global Pensions Asset Study. The latest Mercer asset study suggests that DB schemes invest more in alternatives than the European average (23% vs 20%).29Mercer. Investing in the Future. European Asset Allocation Insights 2021. 2021. Link. However, when these statistics are disaggregated, what counts as an ‘alternative’ is wider than what is indicated by the ‘other’ category in relation to the GPAS. Tor example 37% of UK’s DB ‘other’ asset allocation according to Mercer is invested in growth fixed income, and 25% of the ‘other’ asset allocation is made out of bulk annuities and the LDI strategy. Only 8% of the UK’s alternative asset allocation total portfolio for DB would obviously meet the alternative asset qualification for the Global Pension Asset Survey, and another 30% of the ‘other’ portfolio is made up of hedge funds and diversified growth funds.30Ibid. By contrast, alternatives in the Global Pension Asset Study are clearly meant to mean private assets, namely “real estate, private equity and infrastructure” and these are the dominant element in the Global Pension Asset Study’s definition of ‘other assets’.31Thinking Ahead Institute. Global Pension Asset Study 2022. Link. For its part, the Pension Protection Fund Purple Book, the gold standard when it comes to DB reporting, finds that only 9.1% of DB pension funds in the UK were invested in “other assets”.32Pension Protection Fund. Purple Book 2021. 2021. Link. While it includes private/unquoted equity within equities, counting this in the ‘other’ category would still indicate a 12.9% allocation to alternatives in 2021.33Ibid. See Figure 7.5.

The same dynamic is seen in the UK DC market. Mercer’s study of the DC pension landscape finds that, despite listing the UK’s overall asset allocation at 33%, this allocation is nearly three quarters hedge fund, only 9% real assets and 0% private equity.34Mercer. Investing in the Future. DC Asset Allocation Trends across the UK and Europe. 2021. Link. In short, by the alternative definition this paper seeks to use, which is drawn more closely around productive – and mostly illiquid – assets, Mercer finds that UK DC schemes likely allocate something like 3% to these assets.35Ibid. See Figure 16. In short, and noting the difficulties in getting a true picture of asset allocation, the Global Pension Asset Study survey estimates are reflective of the distribution of the kinds of alternative assets in which this paper focuses, and therefore is a worthy comparative tool across various pension markets. |

Figure 10: Allocation to Other Assets

Global Pension Asset Study – Years 2018-2022

This is not a new problem, and in fact it will likely get worse in the short term, as defined benefit pensions de-risk, for perfectly valid reasons related to their sustainability and the maturing age of many scheme members. As DB schemes close, they will look to invest in less risky assets, in particular bonds or look to pension buy-outs into annuities. As such, in the short term the relative underinvestment problem may According to the Pension Protection Fund, the share of equities as a proportion of UK defined benefit pension schemes has fallen from 61.1% to 19.0% in 2021.36 Pension Protection Fund. The Purple Book 2021: DB pensions universe risk profile. 2022. Link. Alternative asset investment has stayed constant over the last 15 years while the share of investment taken up by bonds has increased significantly. Property investments as a proportion of asset allocation has risen only slightly, from 4.3% in 2006 to 4.7% in 2021.37 ibid

This trajectory has made it even more important then to ensure the defined contribution pension market is able to invest in illiquid assets; DC schemes are projected to be valued at £1 trillion by 2030. If the UK allocated assets like Australian funds could result in £80 billion for infrastructure, £80 billion for other property, £50 billion for unlisted equity, and £10 billion for hedge funds.38 Author’s calculations based on distributions found in ASFA. Superannuation statistics. August 2022. Link.

Currently the scale of this underinvestment has significant implications. For example, despite having the second largest pool of pension assets in the world, only 6% of European VC is raised by UK pension funds – the lowest in Europe. Despite the fact that the UK has a leading financial sector, institutional investors find themselves ‘outcompeted’ for infrastructure assets from other jurisdictions.39 Cipriani, Val. Pension funds ‘outcompeted’ on UK green infrastructure investments. November 29 2021. Link.

Figure 11: Weighted Average Asset Allocation, UK Defined Benefit Schemes

Pension Protection Fund, Purple Book 2021 Figure 7.2

Underinvestment: Insurance

Insurance offers a similar tale of relative underinvestment. Insurance firms in the UK invest significantly less in illiquid assets than similar economies, even though the UK has some of the largest pools of insurance assets in the world.

Figure 12: Solvency II Asset Exposures, Euro Millions

EIOPA

When it comes to private equity, insurance companies the UK is near the bottom as a proportion of investments. While the OECD dataset is incomplete, the data that does exist shows significant differences between jurisdictions, and the relative lack of investment by UK insurers in unlisted equity and land and buildings.

Figure 13: Proportion of Investments in Unlisted Equities, Domestic Undertakings

OECD

Figure 14: Proportion of Investments in Land and Buildings, Domestic Undertakings

OECD

The number are even more remarkable when looking at total balance sheets between Solvency II jurisdictions. Until the end of 2020, EIOPA, the European financial regulator, maintained detailed national balance sheets of every European economy subject to Solvency II. The scale of UK underinvestment is stark. The UK’s total assets at the end of 2020 was the second largest in Europe, aside from France.40EIOPA. Insurance Statistics: Balance Sheet by Item Yet, investments in general made up only 35% of total assets in the UK, compared to 83% in Germany and 76% in France. Moreover, as a proportion of total assets, France invested 28 times more in unlisted equity than the UK, Germany invested 10 times more, and in terms of property41Property for Own Use, Germany and France invested twice as much.

Figure 15: Unlisted Equities, Percentage of Total Assets

EIOPA

Figure 16: Property Not for Own Use, Percentage of Total Assets

EIOPA

In terms of total exposure to various collective investment funds, here too the UK is a relative outlier. Infrastructure funds make up just 12% of the UK’s Solvency II exposure, compared to .34% in Germany and .6% in France. Similarly, UK Solvency II exposure to private equity funds is only 0.19%, compared to .36% in Germany and 0.81% in France.42A full breakdown is available in Appendix 2. Even considering alternative funds, where the UK invests relatively more, the total exposure to infrastructure, private equity and alternative funds is .79% in the UK, compared to 1.0% in Germany and 1.84% in France. Even assuming the UK shifted its allocations in funds to the German level – so 1% of exposures, this would still unlock £4.42 billion. If the UK shifted to the French proportion of investment, it would shift £22 billion into these funds.43EIOPA Insurance Statistics – Exposure Data. Q4 2020.

Overall, it is clear that the UK relatively underinvests in productive assets compared to international and European peers. But, it should also be made clear that this report is not advocating a free for all. While France invests significantly more in unlisted equities, unlisted equities still make up less than 1% of the balance sheet. In terms of property, this still makes up less than 2% of assets in both Germany and France. What this report is advocating is a shift, but a shift of a percentage point at most.

Figure 17: UK Life Sector - Pension Buy-Ins/Buy-Outs

Fitch Ratings44FitchRatings. Pension Risk Transfer Growth Sets UK Life Sector Apart. 9 February 2022. Link.

This is the paradox that sits at the heart of the debate around regional inequality and growth in the United Kingdom: it is the very resources located in London’s international financial markets that can make the most impact. It is often assumed that when speaking about Levelling Up, it is inherently about bending market outcomes, and spending substantial sums of public money on local projects. Conversely, to speak about growth and the venture capital economy is to invite assumptions that one is really concerned with the traditional, financialised, model of UK macroeconomic growth – one centred on London and the South East.

In fact, neither of these narratives does any justice to the current needs of the UK economy. Levelling Up is led by substantial private investment, and that private investment can be catalysed at scale by public investment. The pools of capital, in abundance in London like no other major city save New York, will be a crucial part of ensuring that every part of the United Kingdom is successful. That does not mean that all capital needs to be placed in the UK – indeed a vital part of de-risking a portfolio is ensuring international breadth, but it is certain that pension funds and insurers could invest more in productive assets in the UK. The fact is that these pools of capital have not been put to as good of a use as they should be. This paper looks at insurance and pensions as tools to inject billions into the UK economy, and to power growth in every region of the country.

The Economic Impact of Productive Investment

The economic impact on unlocking capital for productive investment is also clear. The multiplier effect of investing in infrastructure is large, markedly larger than general investment.45Global Infrastructure Hub. Fiscal multiplier effect of infrastructure investment. 14 December 2022. Link. Private investment can have an even greater impact on economic growth.46Unnikrishnan, Nishija and Kattookaran, Thomas P. Impact of Public and Private Infrastructure Investment on Economic Growth: Evidence from India. 9 December 2020. Link. The positive impact of infrastructure growth is now well established in the literature.47Whittle, James. A Short Synthesis of the Link between Infrastructure Provision/Adequacy and Economic Growth. August 2009. Link.

The same is true of private markets and venture capital. The social return of venture capital is significantly higher than business or public research and development.48Romain, Astrid and Pottelsberghe, Bruno van. The Economic Impact of Venture Capital. 2004. Link. A more recent study found that a lack of venture capital funding would lower growth by over a quarter.49Akcigit et al. Synergising ventures: the impcct of venture capital-backed firms on the aggregate economy. 24 September 2019. Link. The same study showed that venture capital backed firms see employment increase by 475%, compared to 230% for other companies.50Ibid.

More broadly, long-term growth capital has a positive impact on the economy. One study looked at over 17,000 firms, and showed that firms with long-term finance were more likely to invest in innovations and have a greater share of permanent employees.51Sommer, Christoph. The Impact of Patient Capital on Job Quality, Investments and Firm Performance. December 2020. Link. Scale-up firms, who are most likely to need growth or patient capital, are net job creators and firms younger than five looking to expand created 2.6 times their share of total employment.52Coutu, Sherry. The Scale-Up Report on UK Economic Growth. November 2014.

Productive investment has significant positive impacts on the economy, but capital is needed. That is where this report seeks to make its impact.

Addressing the Barriers to Success

In order to unleash the promised capital, Government should identify the following four strategic priorities:

1. Creating A Better Regulatory Environment

Government should prioritise a regulatory environment for the financial sector that encourages diversification, policy holder returns, and balances policyholder protection and financial stability with competitiveness and growth.

2. Making A Better Pension Market

Government should prioritise reforming and consolidating the pension market. The UK should look to international comparators, such as the Netherlands, Canada and Australia to find examples of strong pension markets that invest in alternative assets and contribute to economic growth.

3. Empowering Stronger Local Government

Local Government in the UK is fragmented and weak compared to its international peers. Government should look to devolve powers to local communities that reduce political risk increase the ability of local communities to fund local projects with their own resources.

4. Building More Collaborative National Institutions

National institutions in the UK can be better used to encourage productive investment from institutional investors and to create a more collaborative environment. Government should work to ensure that national institutions are as effective as possible in meeting the UK’s investment goals.

To explore how these four strategic priorities can be met, this report proceeds in five chapters.

1. The Investment Case for Illiquid and Alternative Assets

This chapter outlines how and why alternative assets are an important investment option and looks at models where alternative assets have led to high growth. This chapter looks at, , why there is particularly a strong investment case for investment even if UK institutional investors tend to avoid them, relative to international peers.

2. The Regulatory Challenge

Chapter 3 sets out the basic features of institutional investment in the UK, and why institutional investment capital has not been invested in infrastructure, private equity, venture capital and other alternative assets. This chapter examines how Solvency II can be improved, what further changes might be made to the Solvency II regulations, and how regulators can work more closely with firms.

3. Better Pension Markets

Regulatory change is an important aspect of creating better markets. However, it is not enough, on its own, to create the long-term, durable change necessary to unlock capital. This chapter focuses on how the pensions market should consolidate further, so that pensioners and their portfolios can benefit from scale. Chapter 4 also considers arguments around the charge cap, and why it should be deregulated, but only in the context of a consolidating market that returns value for investors.

4. Stronger Local Institutions

Along with fostering better markets through better regulation and better structure, the UK also needs the local and national institutions to create pipelines for projects and the viable investment proposals that can attract institutional investment. Chapter 5 looks specifically at how the current local government landscape is too complicated, is fraught with political risk and lacks some of the key fiscal powers that could be used to de-risk investment and encourage institutional partnership.

5. Better National Collaboration

Local institutions also need to be complemented by national organisations which can fulfil their mandate and deliver investment for local communities. Chapter 6 sets out ways that that they can be improved, by in particular looking at the UK Infrastructure Bank, the British Business Bank, and the Business Growth Fund.

Together, these measures will address the long-term investment challenges the UK faces. As this report demonstrates, the United Kingdom has the resources to face these challenges. It is now time to unleash them.

Next chapterChapter 2: The Investment Case for Illiquid and Alternative Assets

It is sometimes argued that illiquid assets are fundamentally unattractive in the UK context. The argument is that infrastructure, private equity and other alternatives are simply too risky and so should not play a large part in an investment portfolio. This is misguided. The evidence suggests that illiquid assets

- Generate better returns

- Can help hedge against risk by diversifying portfolios

- Can be part of a sound investment strategy

This chapter aims to show why alternative assets are vital to strong investment portfolios.

Illiquidity Risk

It is true that illiquid assets carry risk. Unlike many forms of listed assets, like listed equity, it is harder to price and to hold illiquid assets. Take for example the difference between a stock (listed equity – liquid) and an airport (infrastructure – illiquid).

- Since the stock market has a high number of buyers and sellers, it would be easy to find someone to purchase a stock, and it would be easy to price the asset in question. If you wanted to sell a stock it would be easy to do so without a discount.

- The airport, on the other hand, cannot be bought or sold easily. The market for buyers and sellers is smaller and it is harder to sell on a quick timeline. Moreover, thanks to how illiquid the market is, it is more difficult to price the asset, and so holding this asset lends itself to risk.

Bid-Ask Spread

One of the key differences between liquid and illiquid assets is the size of the bid-ask spread. The bid-ask spread is the difference between the highest bidding price for an asset, and the lowest asking price. Illiquid assets are also subject to a wider ‘bid-ask spread’ than more liquid assets. To be clear, every asset has some sort of spread, but in some cases these can be very small indeed. In currency trading, one of the most liquid forms of trading, the spread is fractions of pennies. In more illiquid transactions, the spreads can amount to a few hundred basis points.

Transaction Costs

The other mark against illiquid assets are transaction costs. Illiquid asset classes can be harder to manage and impose higher transaction costs. Many illiquid assets are complex, have higher management and legal costs, and invariably make the purchase of the asset more expensive. This is why institutional investors that have a strong record in investing in illiquid assets (such as Canadian pension funds), have developed in-house teams to manage assets, to create internal economies of scale. This is discussed further in chapter 4.

Illiquidity thus has some real risks and costs. A famous example of when illiquid assets proved unhelpful is none other than one of the most famous and prestigious institutional investors in the world: the Harvard Endowment. In the lead up to 2009, Forbes described it like this:

For a long while Harvard’s daring investment style was the envy of the endowment world. It made light bets in plain old stocks and bonds and went hell-for-leather into exotic and illiquid holdings: commodities, timberland, hedge funds, emerging market equities and private equity partnerships.53Forbes Magazine, Harvard: the Inside Story of It’s Finance Meltdown. 26 February 2009. Link.

Harvard tried to liquidate its illiquid holdings, particularly private equity, which resulted in significant losses as bidders were demanding significant discounts. This remains one of the most significant examples of where overinvestment in illiquid assets can have a serious, detrimental effect on the underlying strength of a fund.

Liquidity Premium

Because of the risks inherent in illiquid investing, illiquid assets also invite a long-term value premium, otherwise known as the ‘liquidity premium’. This premium is a result of the fact that illiquid assets do have more risk and are harder to convert into cash. This means that over time, illiquid assets should produce higher returns.

While this relationship is complicated, it does appear that many illiquid asset classes do yield higher returns as a result of liquidity constraints. This depends partly on the asset class itself – some research indicates that real estate attracts a higher illiquidity premium than, for example, private equity.54Green, Katie. The illiquidity conundrum: does the illiquidity premium really exist. Schroders. August 2015. Link.

The important role of illiquid assets is borne out when looking at the future – the return picture of illiquid assets is strong.

Return on Investment for Illiquid Assets

Indeed, despite the pitfalls of illiquid assets, they can deliver strong returns for investors. Over the last 10 years, private equity and venture capital has consistently beaten the FTSE 130, 250 and 350, as well as the all-share index.55BVCA & PWC. Performance Measurement Survey 2020. September 2021. Link.

Figure 18: Return Performance

BVCA

Data from Bloomberg also shows strong performance from infrastructure. Between 2004 and 2020, the cumulative return for the EDHEC Infra300 for every USD$100 invested is over $600, compared to just under $400 for the S&P 500 and just over $300 for the MSCI world.56Bloomberg quoted in Mercer, Infrastructure investing – A primer. 2021. Link.

Infrastructure can also be less risky over the long-term. A study by Moody’s found that infrastructure debt was at significantly less risk of default than non-financial corporate bonds over a 10-year span.

Figure 19: Infrastructure vs Non-Financial Corporate Debt Loss Rates, BBB-Rated Debt

Blackrock and Moody’s Investor Services, in Cambridge Associates

Figure 20: Infrastructure vs Non-Financial Corporate Debt Loss Rates, BB-Rated Debt

Infrastructure debt is also long-term, which helps hedge against liability. Infrastructure assets are often regulated, and investors “have a high degree of visibility into long-term cash flows”.57Cambridge Associates, Infrastructure Debt: Understanding the Opportunity. September 2018. Link.

Infrastructure returns are also strong. Compared to global equities, unlisted infrastructure generates higher risk adjusted returns and performs significantly better than global equities over a longer time horizon. Moreover, infrastructure tends to protect against inflation. According to one estimate, listed infrastructure in the United States delivered returns of CPI + 10.1% for the 15 years to 2017.58Colonial First State. Infrastructure as a Hedge to Inflation. June 2018. Link. This is partly because infrastructure assets often have revenue streams indexed to inflation or, in the case of utilities, where regulators typically grant inflation pass-through.59EDHECInfra. Inflation Risk: How Exposed are Investors in Infrastructure?. 2022. Link.

Figure 21: Risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe Ratio)

Global Infrastructure Hub60Global Infrastructure Hub. Infrastructure Equity Performance Shows Attractive and Resilience Returns for Investors. 31 March 2022. Link.

Considering Traditional Investment Strategies

Illiquid assets also play a negligible role in one of the most popular investment strategies, the ‘60/40 strategy, which is often cited as the traditional investment approach. In this strategy, 60% of the portfolio is invested in equities and 40% in bonds. It is a classic strategy because equities can generally secure higher returns and bonds provide a lower risk, so the portfolio is well balanced.

Over the last 10 years, this strategy would have worked quite well. In the United States, a 60/40 split would have outperformed cash by 10.5% over the decade up to September 30 2021.61Mercer, Top considerations for private markets in 2022. 2022. Link.

A 60/40 strategy has also worked in the context of falling interest rates over the last 50 years. Since the 1970s, bond yields have fallen and equities have risen, meaning that a conservative strategy could generate strong returns. In fact, compared to an all-stock strategy, the difference in annualised return is only 0.8%.62Donati, Edward and Johal, Ajay. The 60/40 Portfolio: Losing its balance. Ruffer Investment Management. 2020. Link.

However, the economy has entered an extremely difficult period, and the economic certainties of the past cannot be taken for granted. In the first half of 2022, the S&P 500 fell by 13.34%63Silverblatt, Howard. US Equities Market Attributes July 2022. S&P Dow Jones Indices. 2 August 2022. Link. and the FTSE is down 3% as of June 30.64Guardian Business, Global markets post worst first-half performance in decades. 30 June 2022. Link.

Moreover, these difficulties, while exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and the concomitant energy crisis, are also the result in long-term trends in the economy, such an aging population, declining workforces and continued poor productivity growth.65Schroders, Inescapable investment “truths” for the decade ahead. March 2019. Link. In fact, Schroders put forward a projection of stocks and bonds to 2027,66Prideaux, Charles and Wade, Keith. Inescapable investment “truths” for the decade ahead. Schroders. March 2019. Link. based on these and a variety of other trends, including infrastructure needs and an aging population. This data showed that equity and bond returns over the next decade are expected to drop significantly.

This state of affairs has only been exacerbated by the recent inflation caused by global factors. The high levels of inflation, energy crisis and supply-chain shocks have created a difficult international macroeconomic environment. In Schroders’ latest (2022) 10-year projection, UK and Japanese equity return forecasts improve,67Schroders. 10-year return forecasts (2022-2031). December 2021. Link. while every other forecast is downgraded. Indeed, the prospect for UK bond returns fell by another quarter, and this is before factoring in the war in Ukraine.

Figure 22: Forecasts for Equities Returns (2018-2027)

Figure 23: Forecasts for Government Bond Returns, 2018-2031

Schroders

Current inflation and rises in interest rates have forced stocks down while yields on bonds have also gone up. The S&P 500 fell by more than 20% while yields for 10 year US treasuries went up to 2.5%.68Dohle, Mona. How inflation disrupts the bond-equity correlation. 4 August 2022. Link. In the UK, the FTSE100 has dropped by 4.5% while the yield for 10-year HM Treasury bonds is nearly 2.4%.69Ibid. This makes it harder to generate the proper returns.

Bonds in particular are vulnerable to inflation. While equities can grow as prices rise, bonds see their real value fall thanks to inflationary pressure.70Donati and Johal, 2020.

More broadly than this, countries that have invested in alternative assets have also not seen comparatively weaker performance in their pension funds. Over the last 20 years, the growth rate of the P7 has been strong across the board, except in Japan. Over the last decade, the compound annual growth rate of UK pensions is behind every country (in own currency terms) except Japan.71Thinking Ahead Institute. Global Pension Asset Study. 2022. This is mitigated somewhat by the fact that the UK has comparatively lower pension contributions has a percentage of GDP (except for Canada and Japan)72OECD. Funded Pension Indicators: Contributions as a % of GDP. 2020. Link., but it does indicate that alternatives can play a prominent role in pensions’ investment strategies without sacrificing returns.

Figure 24: Pension Asset Growth, 2001-2021

Global Pension Asset Study, 2022

Assessing the Risks of Liability-Driven Investment

Moreover, ‘traditional’ investment strategies can also be fraught with unintended risk. Investing in alternative assets is not alone in being potentially risky. The UK financial markets have seen over the last number of weeks how Liability Driven Investing (LDI) has led some pension funds to the brink of insolvency.

LDI is based on a few simple rules. It divides an investment strategy into a liability risk portion and a second that aims to seek to higher returns. The liability risk portion of the portfolio is typically invested in bonds, and supplemented with swaps, derivatives and pooled funds.73Insight Investment. An Introduction to Liability Driven Investment. November 2021. Link. These assets are used to ‘hedge’ against liability. However, this hedging, when there are swift changes in the market, require the pension to post collateral if the value of the underlying assets change. This collateral usually has to be posted in the form of cash.74Jones, Huw. Explainer: What is an LDI? Liability-Driven Investment strategy explained. 4 October 2022. Link. In the UK, the risk of potential insolvency was heightened when the markets reacted negatively to the Government’s Growth Plan. As a result of this market reaction, the value of bonds went down and yields went up. Since LDI hedges were predicated on a certain value of bonds, pension funds had to put up cash to maintain the hedge. Pension funds sold bonds to acquire cash, and thus, to maintain their hedges, provoked a spiral of buyoffs. The Bank of England had to intervene with a promise to buy up to £65 billion in bonds to shore up the market.75Bank of England. Gilt Market Operations – Market Notice 28 September 2022. 28 September 2022. Link.

LDI is a strategy based in part on hedging against bond risk, but which required posting collateral (paid for by selling bonds) to maintain these hedges.. Moreover, because of the role actuarial consultants play in many pensions, UK pension plans currently have very similar risk profiles.76Zijdenos, Eric. LDI: The UK Pension Problem and the Risks in Europe. 29 September 2022. Link. Alternative assets allow a degree of risk diversity that would, at least, help prevent the kind of systemic solvency risk that has come to underly the UK’s LDI strategy, while also investing in higher-return, more productive assets than gilts and fixed income.

Next chapterChapter 3: Reducing Regulatory Barriers

The last Chapter dealt with why alternative assets can be a return-generating part of an investment portfolio. However, as shown in Chapter 2, the UK relatively underinvests in many of these asset classes. This is in part due to the regulatory regime currently in place, which poses obstacles to investing in alternative assets.

This Chapter looks at Solvency II and the pension charge cap as particular blockages, but also argues that the broader regulatory attitude should be changed to better encourage competition and growth.

The Regulatory Environment

The UK’s regulatory environment for institutional investment is disparate and spread across multiple institutions. As a result, there has been several different attempts to spur on investment in alternative assets, otherwise known as ‘productive finance’. Some key initiatives have included

- Hill Review (Listings Review)

- The Working Group on Productive Finance

- Creation of the Long-Term Asset Fund Vehicle

- Consultation on Enabling Investment in Productive Finance

- Consultation on the Future Regulatory Framework, culminating in the Financial Services and Markets Bill

- The PRA’s Discussion Paper on Solvency II

In each one of these undertakings there is an awareness that the current regulatory environment leaves much to be desired. It is to be commended that the Government has moved to rectify this situation, and that they have been joined in this by the Labour party.77Conchie, Charlie and Boscia, Stefan, Labour eyes up reform to ’prescriptive’ EU finance rules. 13 July 2022. Link.

Because of how important this issue is, and the billions of pounds of capital at stake, it is important that the Government get the reforms right. This chapter looks at exactly how that might be done, and in particular ways that the Financial Services and Markets Bill, Solvency II Reform and changes to the charge cap can encourage investment.

The Regulatory Bodies

Institutional investors in the UK are regulated through a variety of different organisations, some independent of the Government, others being Government Departments. The below figure spells out in detail the current constellation. The UK is a world leader in regulation, and its regulatory authorities are regularly consulted by others given their justifiably strong reputation. However, that does not mean that there are specific ways to improve the regulatory regime to pursue specific policy goals, in this case greater economic growth and better returns.

| UK Regulatory Organisations – Finance | |

| Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)

The PRA was created in the aftermath of the financial crisis as one of the successors to the Financial Services Authority. The PRA is housed within the Bank of England, and is administered by the Prudential Regulation Committee – one of the two committees at the pinnacle of the Bank of England’s policy-making structure.78The other being the Monetary Policy Committee The PRA has three objectives:

The PRA regulates around 1,500 institutions, including banks, credit unions, major insurers and investment organisations.80PRA, Which firms does the PRA regulate?. Link. |

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

The FCA is, along with the PRA, a successor institution to the Financial Services Authority. The FCA covers around 50,000 different firms and, like the PRA, has three operational objectives:

The FCA has a role in regulating and overseeing pension providers, insurers and other institutional investors. The FCA tends to focus on the consumer aspects of these industries. For example, one of its recent regulatory initiatives was to drive the creation of the ‘pension dashboard’, which “aims to empower savers to engage with their pensions.”81FCA, FCA proposes rules for pension providers to help deliver Pensions Dashboards. 11 February 2022. Link. The FCA has a role in preventing fraud and ensuring consumers use their pensions wisely – hence the ‘safeguarded benefits’ valued at £30,000 or over.82FCA, Pensions and retirement income. 18 April 2022. Link. The FCA also authorises Long-Term Asset Funds, new vehicles to encourage alternative investment. |

| The Pensions Regulator (TPR) The TPR regulates workplace pension schemes, ensuring they are well capitalised and that pension funds have the necessary level of liquidity. TPR has a longer list of statutory objectives:

The TPR and the FCA can operate in conjunction. For example, the FCA and TPR published a joint discussion paper on Value for Money (VfM) in the defined contribution pension market. |

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP)

DWP plays a leading role in regulating and managing pension provision in the UK. While it has a primary role in distributing and setting policy for the state pension, the Department is also the sponsor for TPR. DWP publishes statistics on pensions and is also responsible for managing consultations around the pension charge cap. His Majesty’s Treasury (HMT or The Treasury) HMT plays a central role more broadly in setting all aspects of economic policy, but it is also a driver for a number of initiatives to reform financial markets. The Treasury manages the public service pension schemes, and is responsible to changes in these policies. |

In looking at the various regulatory frameworks, this report will focus in particular on the PRA, as it is responsible for overseeing the prudential aspects of the Solvency II framework, and the FCA and the TPR when it comes to pensions. The FCA also regulates some aspects of Solvency II. However, particularly when it comes to national and local institutions, it is HMT that will be central to the discussions, and they are discussed further in future chapters.

Solvency II

One of the most important regulatory schemes for insurance firms in the UK is Solvency II, a regulatory framework for insurance and reinsurance, enacted in the European Union and which came into force in 2016. It applies to all EU member states, as well as the United Kingdom, which enacted Solvency II in domestic law as a statutory instrument in 2019 following the UK’s departure from the EU.84HMG, The Solvency 2 and Insurance (Amendments etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019. 2019 No. 407. Link.

The Purpose of Solvency II

Solvency II was intended to harmonise prudential regimes throughout Europe. The UK was already operating under a risk-based regime prior to the introduction of Solvency II: Pillar 2 of Solvency I known as the Individual Capital Assessment was a risk-based regime. In pursuing harmonisation, though, Solvency II created an average framework that did not necessarily work effectively for the UK market.

In essence, Solvency II creates tools by which firms can balance policyholder protection with other responsibilities.

Solvency II operates with 3 pillars, described thus by the European Commission:

- Pillar 1 sets out quantitative requirements, including the rules to value assets and liabilities (in particular, technical provisions), to calculate capital requirements and to identify eligible own funds to cover those requirements;

- Pillar 2 sets out requirements for risk management, governance, as well as the details of the supervisory process with competent authorities; this will ensure that the regulatory framework is combined with each undertaking’s own risk-management system and informs business decisions;

- Pillar 3 addresses transparency, reporting to supervisory authorities and disclosure to the public, thereby enhancing market discipline and increasing comparability, leading to more competition.85European Commission. Solvency II Overview: Frequently Asked Questions. 12 January 2015. Link.

Solvency II requires firms to invest according to the ‘Prudent Person Principle’ (PPP) – the PPP has three general objectives underlying it:

- The firm must only invest in assets and instruments the risks of which it can properly identify, measure, monitor, manage, control and report and appropriately take into account in the assessment of its overall solvency needs;

- All the assets of the firm must be: (a) invested in such a manner as to ensure the security, quality, liquidity and profitability of the portfolio of assets of the firm as a whole; and (b) localised such as to ensure their availability; and

- In the case of a conflict of interest, the firm must, or must procure that any third party which manages its assets will ensure that the investment of assets is made in the best interest of policyholders.86Hymans Robertson, Solvency II: Prudent Person Principle. 2016. Link.

Under the previous Solvency I regime, there were no rules preventing investment in specific assets, however only some ‘admissible assets’ could count towards capital requirements.87Clifford Chance, Investments by Insurers under Solvency II. Briefing note, Asset management and funds. May 2016. Link. As a result, the majority of assets held by insurance firms were ’admissible assets’. The ‘admissible asset’ concept has been replaced in Solvency II by the ‘Prudent Person Principle’ (PPP)88, which determines the appropriateness of a specific investment strategy relative to the insurance business it is backing. The distinction between admissible and non-admissible assets no longer exists but instead is context specific for insurers.

Additionally, insurers must calculate a “Solvency Capital Requirement” (SCR) buffer, and use quantitative and qualitative tools to assess the underlying risk of the insurance portfolio. This buffer is to ensure that policy holders are protected and that insurers have the assets necessary to meet their liabilities under extreme stress events89The Solvency Capital Requirement requires insurers to hold a capital buffer to protect against losses occurring over the next year with 99.5% confidence – equivalent to protecting against a 1-in-200 year event. SII Regulations, Art. 101(3) of the Solvency II Directive.

The Matching Adjustment has stricter rules for investments, since it relates to the valuation of long-term, illiquid liabilities where there is a compelling interest for firms to be sufficiently protected to ensure fixed insurance products like (but not limited to) annuities can be paid out regularly. The equivalent to the Matching Adjustment under Solvency I could be applied to all assets, calculated using actuarial judgement, rather than prescriptive rules. That is no longer the case in Solvency II.

Finally, there is the risk margin, which is the difference between an insurers best estimates of liabilities and the (often unobservable) market value of liabilities. 90HM Treasury, Review of Solvency II: Consultation. April 2022. Link. It is used to ensure that, in the event of financial difficulty, an insurance company holds assets equivalent to the amount necessary to transfer liabilities to a third party. 91Ibid.

Solvency II is thus a robust regime, but in some key ways it should be reformed to better balance policyholder protection and other important goals such as growth and competitiveness. Indeed, the PRA itself noted that the Solvency II review it is undertaking is aiming to support insurers’ ability to invest for “long-term growth, and facilitate a thriving, competitive and safe UK insurance sector”.92PRA. DP2/22 – Potential Reforms to Risk Margin and Matching Adjustment within Solvency II. 28 April 2022. Link.

Unfortunately, so far reforms have proceeded slowly, and there are some areas where the Government and the regulator have shown less ambition than would be desirable. Indeed, there are some areas, such as re-examination of Solvency Capital Requirements, where the EU has announced reforms before the UK has even begun to consider them.

This chapter looks at specific areas where reform could make a material difference to the UK’s investment landscape, including those where reform is being considered

- The Risk Margin

- The Matching Adjustment and Fundamental Spread

Others where reforms are not currently being considered, such as

- The Prudent Person Principle

- Rating Illiquid Assets

- Changes to the Solvency Capital Requirement

This chapter then looks more broadly at how to make the regulatory landscape more growth friendly, and ensure that rules designed to protect policy holders and pension scheme members continue to balance that need with the important goals of promoting growth and competition.

The Risk Margin

The risk margin is one area where reform is broadly agreed between the industry and Government. The risk margin, as defined by the Treasury as the “difference between an insurer’s best estimates of its liabilities and the market value of its liabilities”. It is designed to ensure that, in the event of financial difficulty, an insurance company holds assets equivalent to the amount needed to transfer liabilities to a third party.

The risk margin for life insurance in 2021 was larger than £32 billion.93Ibid.

The issue currently is that the existing methodology for calculating the risk margin requires an excessive amount of capital to be held and involves a relatively high degree of volatility, particularly in low interest rates environments. This is the result of the need to use a proxy method to calculate the risk margin, known as the “cost-of-capital” method. Almost as soon as this method was introduced, the industry realised that “the risk margin was both larger than expected and very sensitive to interest rate movements.”94Pelkiewicz et al. A review of the risk margin – Solvency II and beyond. Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, Discussion Paper. British Actuarial Journal. 2020. Link.

The Government has signalled its intention to move to a modified cost-of-capital approach. This would bring the UK in line with proposed reforms in the EU, which would in particular benefit firms which operate in both jurisdictions.95HM Treasury, April 2022.

Moreover, the current calibration of the Risk Margin has resulted in some insurers deliberately reinsuring risk in jurisdictions that are not subject to Solvency II. More broadly, this shifts risk in the UK market from longevity risk to credit risk.

To quote the British Society of Actuaries

The increased use of reinsurance does mean that the success or failure of an annuity writer is now predominantly driven by how well it manages its assets. This is a stark change from the traditional role of life insurers, which was to manage insurance risk.96Pelkiewicz et al. 2020

Government Risk Margin Proposals

The Government proposes a reduction of the risk margin of 60% to 70% by using a modified cost of capital approach. This alone could potentially unlock between £24.4 and £27.3 billion in life and non-life insurance, using the amount currently held in risk margin capital.97Relative to the £32 billion currently held in the risk margin. This in itself would be a welcome change.

Pelkiewicz et al. noted that a “more fundamental re-think” may be needed. It should be noted that when the Association of British Insurers considered this question, they considered a 75% reduction in the risk margin “optimised for the UK”.98KPMG, Report on economic impacts of potential changes to insurance regulatory framework in response to HM Treasury Review of Solvency II: Call for Evidence. Association of British Insurers. February 2021. Link. In that context, a 60% to 70% reduction in the risk margin using the same fundamental approach is somewhat unambitious. Furthermore, the potential release of capital is calculated before the impact of transitional measures on technical provisions (TMTPs), which will act to offset the majority of the release for large firms.

There are other approaches to calculating the risk margin that have also been explored. In particular, the Margin over Current Estimate (MOCE) approach would help achieve Solvency II Equivalency (like a modified cost of capital approach) since it is being developed by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors, and could involve a simple calculation. A prudence based MOCE, which adds a margin to best estimate uncertainty, would involve using international capital standard (ICS) risk charges and adding a small margin. This has the potential to reduce administrative burdens. It would also conform to international approaches.

In any case, it is desirable that Government is changing the risk margin, but this could go further still, and more capital could be unlocked than what is currently proposed. This is particularly the case given current proposals in relating to the Matching Adjustment (MA) and the Fundamental Spread (FS).

Matching Adjustment and the Fundamental Spread

Changes to the risk margin are to be welcomed, but these are undermined by the Government’s proposals to change the matching adjustment and fundamental spread at the same time, which evidence from Willis Towers Watson suggests will make it harder to invest in alternative assets.99Willis Towers Watson. Analysis of Proposed Solvency II Reforms. 21 July 2022. Link. The PRA proposals risk hindering the wider government thrust for investment in productive assets.

The Matching Adjustment is a tool by which insurers can realise some of the liquidity premium on their investments in liability valuations. This means that insurers are required to hold less capital than they otherwise would have.100PRA. DP2/22 – Potential Reforms to Risk Margin and Matching Adjustment within Solvency II. 28 April 2022. Link. It is alternatively described by the PRA as a way insurers can recognise capital resources up-front to invest.101Ibid. It is not, however, ‘free money’ as insurers must maintain the proper risk practices when investing.

The PRA asserts that in its current form the matching adjustment does not adequately reflect risk because of the way the Fundamental Spread (FS) is calculated. The FS is designed to take into account the cost of default and downgrades when the matching adjustment is calculated.102Actuarial Post, Solvency II Fundamental Spread: Annuity prices remain steady. 2015. Link. The PRA argues that, currently, there are three major concerns:

- The FS does not capture all retained risks which insurers face and as such its level (in basis points) is generally too low;

- The FS is not sensitive to differences in risks across asset classes for a given currency, sector and Credit Quality Step (CQS); and

- The FS does not adjust to reflect structural shifts in the credit environment over time, unless there are actual defaults or downgrades.103PRA, 28 April 2022.

To quote the Deputy Governor for Prudential Regulation, in a speech he gave at a Bank of England Webinar in July of 2022,

“…our experience of operating the MA suggests to us that the broad mechanism works but that the EU design makes insufficient allowance for uncertainty, the difference in riskiness between assets, and signals from the market. As a result of this, we are concerned that it over-estimates the portion of future returns which can confidently be assumed to be free of risk for insurance companies and therefore safely banked as capital up-front.”104Woods, Sam, Solvency II: Striking the balance – speech by Sam Woods. Bank of England/PRA. 8 July 2022. Link.

Risk Margin and Matching Adjustment Reform Potentially At Cross-Purposes

The risk here is that the fundamental spread reforms will undermine the broader thrust of reforms. A newly calculated fundamental spread would significantly decrease the value of the matching adjustment and the ability of insurers to recognise liquidity premiums. To put the risk margin and capital adjustment in context, as stated previously the risk margin amounts to slightly under £40 billion, while the PRA estimates that the current matching adjustment constitutes a benefit of around £80 billion, or twice as large.105Ibid. Indeed, Woods notes that ”for a number of insurers the MA by itself makes up the bulk of their capital.”106Ibid.

There is disagreement currently between the industry and the PRA in terms of the proposed changes to the fundamental spread. The Association of British Insurers are clear: “the current proposals would not achieve the suggested release of 10 to 15% of capital for re-investment”.107ABI, Solvency II reform proposals need further work to meet objectives. 21 July 2022. Link.

There are two particular concerns that have been raised with Policy Exchange and which should be taken into account in terms of further discussions

- A lack of evidence in relation to the inadequacy of the current fundamental spread calculations

- A failure on the part of the PRA to consider the market conditions of various asset classes (particularly productive assets)

A Relative Lack of Evidence