Authors

Content

Foreword

Peter Clarke CVO OBE QPM

Former HM Chief Inspector of Prisons and Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Service.

The Criminal Justice System is in crisis – something that no serious commentator should seek to deny. This Policy Exchange report describes the crisis as ‘nothing less than a catastrophic public safety failure’. That is no exaggeration, but an entirely accurate description of what has happened.

The Crown Prosecution Service is taking longer to charge suspects and bring them before the courts than ever before. The enormous backlogs in the Crown Courts mean that victims, witnesses, defendants and indeed the wider public are waiting, sometimes for years, before cases are brought to trial.

The prison population is growing and in the near future will exceed capacity. The numbers are already far beyond what can be held in decent, purposeful conditions. In fact, many prisons are in a disgraceful state, and as a result are deeply counter-productive. Far too often prisoners are confined in their cells for long periods, unable to gain access to the training, work and education that are key to any realistic chance of rehabilitation. There is no public interest in keeping prisoners in filthy, often drug filled and violent jails. When released, they are more likely to reoffend than if they had been treated decently. As a result, failing prisons are actually creating crime rather than deterring it.

Most crimes are committed by a relatively small proportion of offenders. They cause havoc, damage and distress in their communities. They lead lives that are dangerous both to themselves and those around them. Many are addicted to drugs or alcohol. At the moment there is little in place to help set them on a better path. The Criminal Justice System is failing to protect the public from the depredations of these prolific offenders. It is also failing the many offenders who would like to turn their lives around but need help in order to do so.

Many, many offenders, even some of the most prolific and vicious, have the potential to live a better and more productive life. But this will only happen if they are brought before the courts swiftly, their cases dealt with promptly, and if sentenced to imprisonment, given a realistic chance to mend their ways.

It is very well known what contributes to prisoners being less likely to reoffend. The maintenance of family ties while in custody, access to secure accommodation on release, and employment. We know what works, but all too often the system stops these outcomes from being achieved. This is a massive policy failure that directly harms the public. Many of us have been saying this for years, but the situation has now reached a level of seriousness that urgent and effective action is needed.

When I was HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, and before that as a police officer, I frequently had the pleasure of meeting incredibly dedicated and highly professional people working within the Criminal Justice System. They were determined to make things better. Sadly, all too often they were frustrated in their ambitions, often by the failures that are highlighted in this report. They deserve better. The public deserve better. Those who would like to change their own behaviour for the better, deserve better.

I have worked in and around the Criminal Justice System for some 46 years and have seen successive governments fail to make meaningful improvements. The overriding objective must surely be to keep the public as safe as is possible under the rule of law. To achieve that, there will have to be exceptional levels of determination and leadership from ministers, officials and operational staff in all disciplines. Is it too much to hope that this can be done in a way that is truly collaborative, avoiding the adversarial impulses and ideological barriers that all too often have got in the way of delivering better outcomes?

For many years Policy Exchange has been at the heart of the debate on how best to shape an effective Criminal Justice System. The recommendations in David Spencer’s excellent report, if treated as seriously as they deserve to be, offer an opportunity to start the recovery from the immediate crisis and in the longer term build lasting, effective improvements. In the short term though, there is an urgency to implementing those measures that will help prevent crime and disorder in our communities, and thereby meet the first duty of Government – the protection of its citizens.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

The Criminal Justice System in England and Wales is in crisis. The Government has announced that it plans to introduce a series of initial measures to ensure that the prison population does not exceed the current capacity. These include reducing the number of short sentences for non-violent and non-sexual offenders, deporting Foreign National Offenders earlier in their sentence and increasing GPS tagging of offenders serving their sentences in the community. These measures are to be welcomed. They are, of course, only the initial steps of many that must be taken.

We should be in no doubt that we face nothing less than what has become a catastrophic public safety failure. An effective Criminal Justice System is central to the operating of a functioning State – protecting its citizens is one of the first responsibilities of Government. Although there are of course exceptions, the ministers and officials who have been responsible for our Criminal Justice System arriving at this point have put the public at grave risk from dangerous and prolific offenders.

Central to this crisis is a system which fails to deal sufficiently strongly with the cruel, violent or unapologetically prolific – the Wicked; and yet limits the opportunities for a new life for the vulnerable, unwell or exploited – the Redeemable.

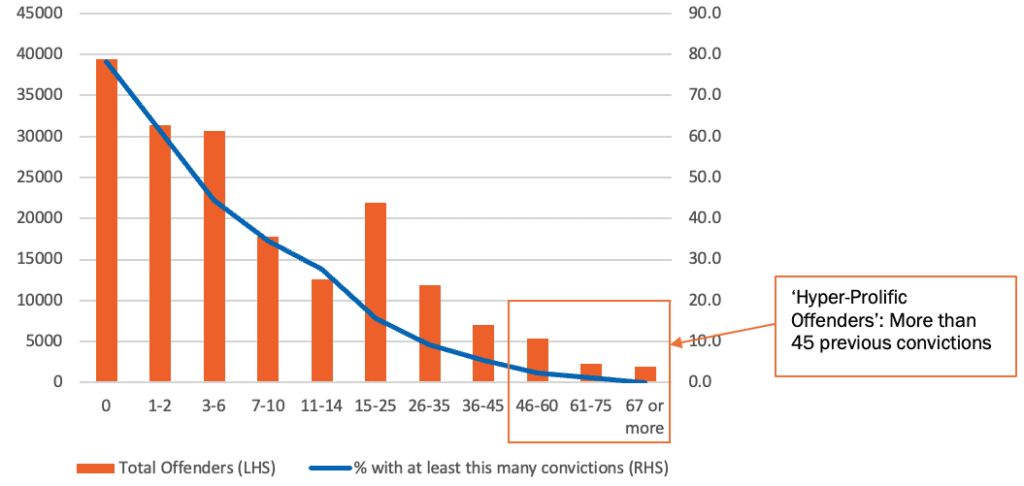

Most crimes are committed by a small proportion of offenders. Despite representing only nine percent of the nearly six million people convicted of committing a criminal offence between 2000 and 2021 prolific offenders represent nearly half of all sentencing occasions and just over half of all convictions.1Ministry of Justice, Prolific Offenders: Update on the characteristics of prolific offenders, 2000-2021, link Prolific offenders are convicted of eight times as many offences as non-prolific offenders – an average of 20.14 offences for prolific offenders compared to 2.49 offences for non-prolific offenders.2Ibid

More remarkably, there are a group that we call ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ – those individuals who have accumulated at least 45 previous convictions in their lifetime. Individuals falling into this category were convicted or cautioned of an ‘either-way’ offence on 9,668 occasions in the year to December 2022.3‘Either-way’ offences are those which can either be tried ‘summarily’ in the Magistrates Court or on ‘indictment’ in the Crown Court. They include Burglary, Actual Bodily Harm or Possession With Intent to Supply Drugs Despite the hugely negative impact this relatively small group of individuals have in communities, astonishingly on 52.7% of occasions they were not sentenced to a term of imprisonment.4Ministry of Justice, First time entrants (FTE) into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories: year ending December 2022, link

Even with this group of ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’, it is worth noting that there are individuals who are redeemable. Currently, however, the Criminal Justice System fails both to adequately protect the public from them and their criminal activities, and to take the opportunity to set them on a pathway to, with the right interventions, living righteous and productive lives.

Meanwhile, the current state of the Criminal Justice System is a public safety time bomb.

It is taking longer to charge suspects of crimes. The median length of time to charge suspects from the point that the Crown Prosecution Service receives a case file from the police has tripled over the last seven years – from 14 days in March 2016 to 44 days in March 2023.5Home Office, Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2022 to 2023, link

Backlogs in the criminal courts are causing victims, witnesses, defendants and the public to wait, in some cases for years, before justice is done. By June 2023 there were over 64,709 cases waiting to be dealt with in the Crown Courts – the highest ever recorded and almost double the number outstanding in December 2018.6Ministry of Justice, Criminal court statistics quarterly, April to June 2023, link The number of cases which have been outstanding for over six months has more than quadrupled over the last four years – from 6,880 cases in June 2019 to 30,384 in June 2023.7Ibid

The prison population is growing and without substantial intervention will soon exceed the prison system’s capacity. The conditions of many of our prisons are a disgrace, with prisoners rarely able to undertake the education or purposeful activity which would reduce the risk of them reoffending on release. During 2022-23 His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons conducted 37 inspections of prisons and young offender institutions holding adult and young adult men. Relating to ‘purposeful activity’ only one was reported to be ‘Good’.8HM Inspectorate of Prisons, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2022-2023, link Of the remainder, 17 establishments were rated ‘Not sufficiently good’ and 19 were given the lowest possible rating – ‘Poor’.9Ibid

Reoffending rates of those leaving prison are unacceptably high, putting the public at huge risk. For offenders who had started a community order (including suspended sentences) in the most recent period for which data is available, the proven reoffending rate was 30.6%.10Ministry of Justice, Proven Reoffending Statistics Quarterly Bulletin, July to September 2021, link For those who had served a short sentence of less than 12 months the rate was far higher, at 55.1%.11Ibid Overall, 25% of offenders were convicted of reoffending within 12 months.12Ibid The annual economic costs of reoffending are estimated to be £18.1 billion.13A. Newton, X. May, S. Eames & M. Ahmad (2019), Economic and Social Costs of Reoffending: Analytical Report, Ministry of Justice, link The cost in the human suffering of victims, families and communities is surely incalculable.

This report proposes a policy programme which would start to turn around the Criminal Justice System; with a particular focus on differentiating between the cruel, violent or unapologetically prolific – the Wicked; and the vast majority of offenders – the Redeemable.

The recommendations in this report are focused on three areas.

Sentencing reform: A new approach to sentencing offenders is required – one that explicitly links the totality of offenders’ criminal behaviour to the sentence they receive on conviction. We recommend a two-year mandatory sentence for Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ each time they are convicted of a further ‘either-way’ or indictable criminal offence.14‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ are those who have accumulated at least 45 previous convictions in their lifetime. For those responsible for committing criminal offences who are neither prolific nor violent offenders we recommend the use of a range of alternate means of ‘disposal’ – including an expansion of ‘Deferred Prosecutions’ and non-custodial, yet highly consequential, community-based sentences.

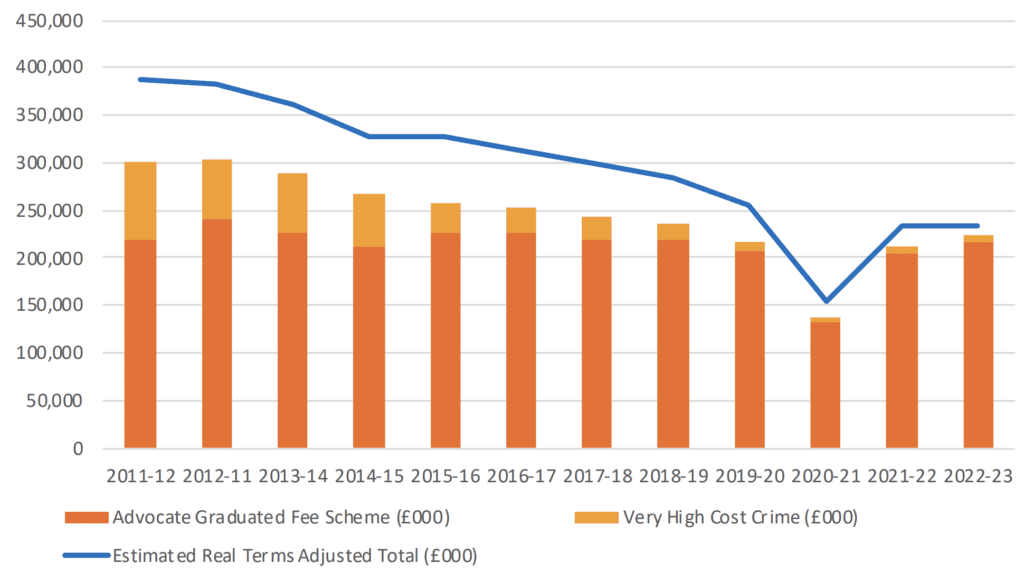

Swift justice: Key to deterring offenders from committing criminal offences is dealing with individuals as rapidly as justice will allow. We therefore recommend stripping away the bureaucracy for charging prolific offenders, where there is clear evidence of the offence. We propose increasing the powers of the Magistrates Courts to deal with more cases enabling justice to be done more quickly. As Thatcher recognised when she increased police officer salaries following the Edmund-Davies Committee Report (1977-1979), an effective justice system relies on appropriately renumerating those responsible for its operation. We therefore recommend increasing the publicly funded fee payments to barristers acting in criminal cases.

Prison reform: In recent years the prison and probation system have represented a catastrophic example of State failure. Substantial reforms are required. An increase in autonomy and accountability for prison Governors is necessary, alongside a reformed salary structure which recognises high-performers and encourages them to remain in challenging operational roles. A reduction in the bloated and stifling bureaucracy across the Ministry of Justice and His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service should urgently be undertaken. A reformed model of recruitment and training for prison officers, which recognises the full complexity of the role, is required. Central to any performance regime should be whether Governors are able to maintain a safe, drug-free prison environment which successfully prepares prisoners for employment on release. Through a new model for women in custody and on release could increase the capacity to deal with the most dangerous and prolific offenders.

The Criminal Justice System is in urgent need of reform. This report proposes the necessary next steps to fixing this crisis.

Next chapterSummary of Recommendations

Sentencing reform

- The Government must introduce legislation that requires Magistrates (extending the existing sentencing powers for Magistrates) and Crown Court Judges to sentence Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ to a minimum term of imprisonment of two years in custody on conviction for any further ‘either-way’ or indictable criminal offences.

- For Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ sentenced to a minimum term of imprisonment, legislation should be introduced which places obligations on His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service that these offenders receive a ‘Mandatory Individual Intervention Plan’ for the duration of their time in custody (for example including mandatory drug addiction treatment, education or skills programmes).

- ‘Deferred Prosecution’ programmes should be expanded to all police force areas under a consistent framework with an amendment to the Home Office Counting Rules so crimes which are dealt with through Deferred Prosecution can be shown as having been ‘solved’.

- The Government should seek to expand the use of non-custodial sentences for non-violent offenders as an alternative to short-term prison sentences while also making community sentences more consequential for offenders. This should include setting out in legislation that:

- There should be a presumption in favour of community-based sentences rather than short-term prison sentences for non-violent and non-prolific offenders.

- When sentencing offenders to a community-based sentence Judges and Magistrates should be required to outline in detail which conditions they are applying and which conditions they are not, and for each why they have made that decision.

- In all cases where a suspended sentence is given community-order type conditions should also be applied.

- The amount of time which can be applied to unpaid work requirements be expanded.

- Home Detention Curfews should be expanded for non-violent prisoners who have served the vast majority of their sentence, with the remainder to be served in the community.

Swift justice

- In all cases where the suspect is a prolific offender the Crown Prosecution Service should review the evidence under the Threshold Test – if necessary the Government should amend the Bail Act 1976 to enable this.

- In all cases which are ready to be reviewed under the Full Code Test the Crown Prosecution Service must revert to providing in-custody charging advice.

- For non-complex cases where the suspect is not in custody or is on bail the timescale for the Crown Prosecution Service to provide advice should be reduced from 28 days to seven days. The new Director of Public Prosecutions should be held to account for achieving this within one year of his term of office commencing, on the 1st November 2023.

- Combined with other recommendations in this report on a trial basis Magistrates Courts sentencing powers, should be increased to a maximum of two years in custody for a single ‘either way’ offence.

- In addition to the 15% increase in publicly-funded fees already secured for advocates working in the Crown Courts the Government should immediately apply a further increase of 10%.

Prison reform

- An urgent review of all non-operational Ministry of Justice and His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service posts should commence immediately. The number of non-operational posts must be reduced to 2018 levels, with the budget shifting to investment in senior operational roles.

- The Government must extend the pay scales for senior prison Governors in order that that they are able to progress their career and renumeration while remaining in frontline operational roles.

- The Government should introduce a clear means of appropriately and publicly holding the leaders of each prison to account for achieving the highest possible standards. This should focus on running a safe, drug and corruption free prison environment alongside a focus on the factors which lead prisoners to be more likely to subsequently desist from crime.

- A widespread transformation in the recruitment and training of prison officers must be implemented by Government without delay. This must focus on the raising of standards across the profession to enable prison officers to deliver the sort of modern-day prison service which has the potential to reduce reoffending for the most prolific offenders on release.

- The Ministry of Justice should accelerate the progress towards opening the five planned Residential Women’s Centres across the country. In each case they should be delivered in partnership with a social enterprise rooted in the local community. These Centres must exclusively be for female offenders.

The Current State of Criminal Justice System

The Criminal Justice System is in crisis. Policy makers should be in no doubt – the failings in the Criminal Justice System are putting the public at greater risk from crime and those who commit crime. The status quo across the entirety of the Criminal Justice System, including our courts, prisons and probation services, is nothing short of a public safety time bomb.

‘Justice Delayed is Justice Denied’

The median number of days to charge a suspect has increased from 14 days in the year to March 2016 to 44 days in the year to March 2023.15Home Office, Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2022 to 2023, link In most cases in England and Wales the police are responsible for conducting criminal investigations and the Crown Prosecution Service is responsible for their prosecution. Decisions about whether to prosecute suspects generally reside with the Crown Prosecution Service.

The increasing delays may have several causes, including the increasing complexity of investigations – it cannot solely be accounted for by the Covid-19 pandemic. The median number of days to charge suspects had already reached 33 days by March 2020.16Ibid In many cases it is entirely avoidable bureaucratic hurdles which are causing unnecessary delays before cases even reach a court room.

The median number of days from an offence being committed to the decision being reached to charge or summons the suspect (Year to March 2016 – March 2023)17Ibid

The Covid-19 pandemic had an impact on Magistrates’ Courts, although substantial progress has been made in reducing this backlog. Once the decision has been taken to charge or summons a suspect all cases start in the Magistrates’ Court. Less serious criminal cases remain for trial in the Magistrates’ Court while the most serious cases move to be tried in the Crown Court. The number of outstanding cases in the Magistrates’ Courts was increasing prior to the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, from 282,245 in September 2019 to 327,937 in March 2020 – an increase of 16.19%.18Ministry of Justice, Criminal court statistics quarterly, March to June 2023, link During the pandemic the number of outstanding cases peaked at 422,156 in June 2020, however the number of outstanding cases has now reduced to 345,285 cases in June 2023.19Ibid

The number of outstanding Magistrates’ Court cases (England & Wales) (March 2012 – June 2023)20Ibid

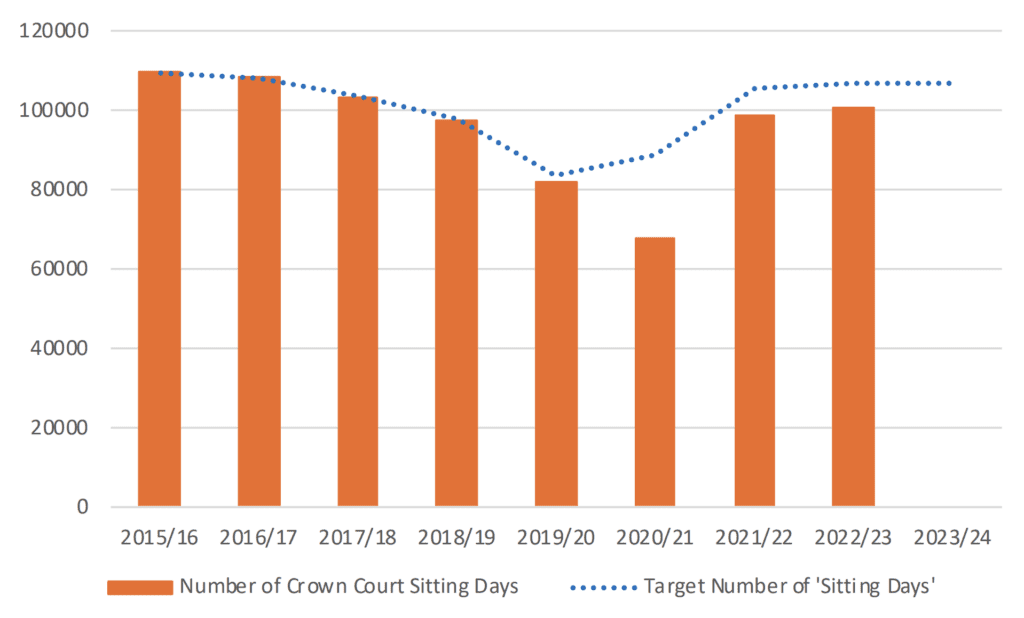

Over the last four years the number of outstanding cases in the Crown Courts has increased substantially. These backlogs in the Crown Courts are causing victims, witnesses, defendants and the public to wait, in some of the most serious cases, years before justice is done. In the year leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of outstanding cases in the Crown Court increased by 15.4%, from an all-time low of 32,886 in December 2018 to 37,964 in December 2019.21Ibid During the pandemic, with courts closed or at substantially reduced capacity, the number of outstanding cases reached 60,688 by June 2021.22Ibid Following a slight post-pandemic reduction to 57,923 cases by March 2022, the number of cases has now increased substantially – to 64,709 in June 2023.23Ibid This is the highest number of outstanding Crown Court cases ever recorded.

The length of time cases are taking to be dealt with by the courts has increased substantially – to the detriment of victims, witnesses, defendants and the public. The Better Case Management principles set out since 2016 establish that cases should take no longer than six months from receipt in the Crown Court to the start of trial (assuming that the defendant pleads not-guilty). Prior to the pandemic the number of cases which had been outstanding for over six months had increased by 53.7%, from 7,031 cases in March 2019 to 10,810 cases in March 2020.24Ibid Since March 2020 the number of cases which have been outstanding for over six months had increased by a further three-fold to 30,243 cases in March 2023, with a peak of 30,888 cases in December 2022.25Ibid While the pandemic has substantially contributed to the failure to deal with cases in a timely manner it is also clear that the issues in the Crown Court pre-date the pandemic.

The number of outstanding Crown Court cases (England & Wales) (June 2014 - June 2023)26Ibid

The Prison Service: Universities of crime?

The prison population is growing and projected to far exceed the prison estate’s current capacity. The last three decades have represented a significant increase in the number of individuals held in prison custody. In October 2023, the most recent data available, the prison population was 88,225 individuals27Ministry of Justice, Prison Population bulletin 12th October 2023, link – an increase of 44.4% on the 61,114 individuals held in prison custody in 1997.28Ministry of Justice, Offender Management statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link Over this period the prison population rate has increased from 117 prisoners per 100,000 population to 148 – an increase of 26.4%. The prison population is projected to reach between 92,250 and 105,600 individuals by November 2026.29Ministry of Justice, Prison population projections: 2022 to 2027, link As of October 2023, the maximum capacity of people who could be held in the prisons of England and Wales is 88,782.

The Government has announced that it plans to introduce a series of initial measures to ensure that the prison population does not exceed the current capacity. These include a presumption against short sentences for non-violent and non-sexual offenders, the early deportation of Foreign National Offenders held in English and Welsh prisons and an increase in the use of GPS tagging for those serving community-based sentences. Each are to be welcomed. These are, however, merely the necessary initial steps to be taken. If we are to solve the crisis that so clearly exists across the entire Criminal Justice System it is essential that further steps towards reform are implemented.

The England & Wales prison population (1998 – 2023) and projected population (2024 – 2027)30Data for 1997-2022 is based on 12-month prison population average: Ministry of Justice, Offender Management statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link; Data for 2023 is based on Ministry of Justice, Prison Population bulletin 12th October 2023, link; Data for 2024–2026 is based on Prison Projections: Ministry of Justice, Prison population projections: 2022 to 2027, link

Most prisoners are serving ‘determinate sentences’, where a court has specified how long their sentence should be. A not insignificant 11.9% of prisoners however are un-convicted and awaiting trial on remand.31Ministry of Justice & HM Prison and Probation Service, Offender Management Statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link The vast majority of prisoners are male, representing 96.1% of those in custody.32Ibid As of August 2023 there were 456 children (between the ages of 10 and 17) in custody.33HM Prison and Probation Service, Youth custody data: August 2023, link 13 of those children are between the ages of 10 and 14 years old.34Ibid

| Type of Sentence (as at 30th June 2023)35Ministry of Justice & HM Prison and Probation Service, Offender Management Statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link | Proportion of Prisoners |

| Remand (Awaiting trial) | 11.9% |

| Remand (Convicted and awaiting sentence) | 6.2% |

| Less than or equal to 12 months (incl. Fine Defaulters) | 4.3% |

| Greater than 12 months to less than four years | 15.3% |

| Four years or more (excluding indeterminate sentences) | 37.5% |

| Indeterminate sentences | 9.9% |

| Recalled to Prison36Where a prisoner has been released ‘on licence’ they are supervised by an Offender Manager in the community. On release, they receive a copy of their licence with the conditions they need to adhere to. If they do not keep to the conditions of their licence they can be recalled and returned to prison. | 13.9% |

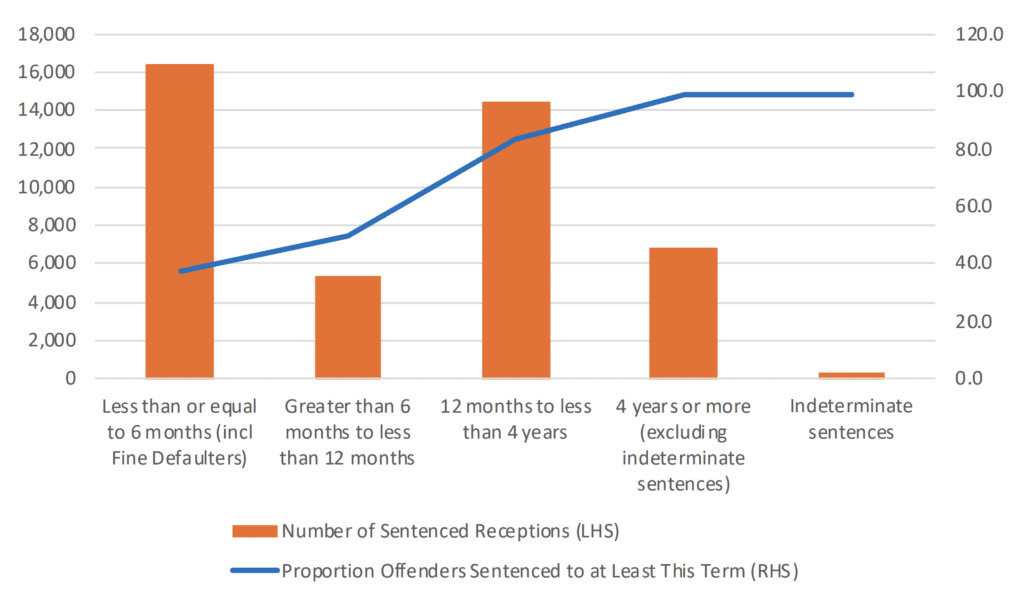

The turnover of prisoners through the system is considerable, with most entering and leaving prison in less than 12 months. Half of those entering the prison system every year do so for a ‘short term’ of imprisonment (which we define as being those sentences of less than 12 months).37Ministry of Justice & HM Prison and Probation Service, Offender Management Statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link In the year to March 2023, of the 43,608 individuals sentenced to immediate terms of imprisonment only 7,116 of them were sentenced to serve more than four years in custody.38Ministry of Justice & HM Prison and Probation Service, Offender Management Statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link Of those receiving immediate custodial sentences 31.3% were for violent, sexual, robbery or weapons related offences; 14.9% were for drugs offences; 15.8% for fraud or theft; and 6.3% for the possession of weapons.39Ibid

The number of individuals sentenced to immediate terms of imprisonment by offence group (England and Wales) (year to March 2023)40Ibid

The conditions of many of our prisons are a disgrace, and in far too many cases are quite simply insufficiently safe and sanitary for any human’s habitation – whatever crimes those people may have committed. 88 prisoners committed suicide in the year to March 2023, a 26% increase on the previous year.41Ministry of Justice, Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales, 27th July 2023, link In the 12 months to March 2023 there were 22,319 assaults, an increase of 11% on the previous year.42Ibid Of those assaults 2,654 were classified by the prison service as being ‘serious’, an increase of 23% on the previous year.43Ibid Prisons are far from the ‘holiday camp’ environment they are often presented to be in popular discourse. Prison establishments are often dangerous and frightening places.

| “At more than half the adult men’s establishments we inspected this year, we highlighted weaknesses in measures to prevent suicide and self-harm, including poor oversight and a lack of planning to improve outcomes. At some prisons there was insufficient analysis of data to understand the main causes of self-harm, and at others, serious incidents were not systematically investigated to learn the lessons.

Prisoners repeatedly told us that the frustration and anxiety caused by long periods locked up, and a lack of purposeful activity and interventions, contributed to self-harm. The poor regime also limited the quality of relationships between staff and vulnerable prisoners; in our survey, only 45% of prisoners on assessment, care in custody and teamwork (ACCT) case management said that they felt cared for by staff.” HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Annual Report 2022-202344HM Inspectorate of Prisons, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons Annual Report 2022-2023, link |

The management of risk within our prisons and on release is grossly misunderstood. Too often offenders convicted of very serious crimes but who are apparently ‘well-behaved’ and ‘compliant’ while in custody are assessed at a lower risk than they should be despite representing a very grave risk to the public and other prisoners.

Despite considerable evidence on how they could be reduced, reoffending rates remain high. For offenders who had started a community order (including suspended sentences) in the most recent period for which data is available, the proven reoffending rate was 30.6%.45Ministry of Justice, Proven Reoffending Statistics Quarterly Bulletin, July to September 2021, link For those who had served a short sentence of less than 12 months the rate was far higher, at 55.1%.46Ibid Overall, 25% of offenders were convicted of reoffending within 12 months.47Ibid The proven rate of reoffending over the last decade has been fairly stable, fluctuating between 22.7% and 30.6% since 2010.48Ibid Perhaps unsurprisingly, the more previous convictions a prisoner has, the more likely they are to then be reconvicted.49Ibid

Percentage of offenders (England and Wales) who commit a proven reoffence within one year by the number of previous offences (July - September 2021 offender cohort)50Ministry of Justice, Proven Reoffending Statistics Quarterly Bulletin, July to September 2021, link

In too many cases prisoners are rarely able to undertake the education or purposeful activity which might reduce the risk of them reoffending on release. During 2022-23, His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons conducted 37 inspections of prisons and young offender institutions holding adult and young adult men. Relating to ‘purposeful activity’ only one was reported to be ‘Good’.51HM Inspectorate of Prisons, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2022-2023, link Of the remainder, 17 establishments were rated ‘Not sufficiently good’ and 19 were given the lowest possible rating – ‘Poor’.52Ibid 42% of prisoners report being locked in their cell for at least 22 hours a day, with this rising to 60% on weekends – both over double the proportion before the Covid-19 pandemic.53Ibid The annual economic costs of reoffending are estimated to be £18.1 billion.54A. Newton, X. May, S. Eames & M. Ahmad (2019), Economic and Social Costs of Reoffending: Analytical Report, Ministry of Justice, link The cost in the human suffering of victims, families and communities is surely incalculable.

While there are many hard working and committed public servants working in our prison system, the Prison Service has a prevailing leadership culture of low accountability and low standards. The administrative and bureaucratic leadership of the Ministry of Justice and His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service has ballooned, while the number of those on the operational frontline has barely experienced any growth at all.55Ministry of Justice, HM Prison and Probation Service workforce quarterly: June 2023, link & Ministry of Justice, Workforce management information, link Governors often have insufficient autonomy to make decisions which would lead to better and more efficiently run prisons, considerable improvements for prisoners and reduced risks to the public once prisoners are released. In particular, the centrally mandated system of procurement and contracting is Byzantine and ineffective. When even the most egregious failings are identified, it is rare that anyone is genuinely held to account.

Public confidence in the Criminal Justice System

There is a strong sense that the public believe that sentences handed down by the courts are too lenient. 71% of the public believe that sentences are too lenient with 38% of respondents believing that they are much too lenient.56Ibid Based on recently published Justice Select Committee data, the public believe that the most important factors in sentencing should be protecting the public, followed by ensuring the victim feels they have secured justice and punishing the offender.57House of Commons Justice Select Committee, Survey of 2,057 adults in England and Wales (24th February to 1st March 2023), link

Despite the evident crisis across the Criminal Justice System this is a crisis which appears beyond the concern, or at least the conscious attention, of the vast majority of the public. In October 2020 the Ipsos Issues Index recorded that the public’s belief that crime, law and order was one of the most important issues facing the country (compared to other issues) was at its lowest level since 1974.58Ipsos Issues Index, September 2023, link In September 2023 only one percent of the public rated crime, law and order as the most important issue facing the country today.59Ibid

However, while the public may not consider crime, law and order one of the most important issues facing the country today, the public’s confidence in the Criminal Justice System is tenuous at best. The most recent available data as part of the Crime Survey of England and Wales (conducted during 2019/20) suggests that only half of respondents believe that the Criminal Justice System as a whole is effective.60Crime Survey of England and Wales, Confidence in the criminal justice system, year ending March 2014, March 2018 and March 2020, link

Public confidence in the Criminal Justice System (England & Wales)61Ibid

A New Approach – the Wicked and the Redeemable

Central to the purpose of the Criminal Justice System is protecting the public and punishing those who would do harm in our society. The criminal law, as laid down by Parliament, codifies the extreme limits of what is acceptable behaviour in our society and makes clear the sanctions to be imposed on those who choose to breach those limits. The courts make judgements and, where appropriate, impose sentences which both deter others and fairly meet the harms done. Swiftness and certainty should be at the heart of the criminal courts system.

Prisons isolate dangerous offenders from the rest of society, contributing to safer homes and communities. They also punish those who have chosen to breach the norms of our society by depriving them of their liberty. People who have been sentenced to terms of imprisonment have often caused the most awful harm to others in society. They have broken lives, destroyed families, deprived victims and damaged communities. There is a moral imperative that in such circumstances they be punished.

But while prisons may work in one sense, in that they isolate and punish, in others they do not. To balance justice and mercy the Criminal Justice System should be a place where redemption is possible. Currently, for too many, it is not. There are those who, whatever resources and opportunities they are given, will break the rules and norms our society holds dear. For those, the Wicked, it is entirely right that they are subjected to extended periods of imprisonment, isolated from society. The vast majority of those who pass through the Criminal Justice System however, if given the opportunity, are capable of leading moral and productive lives. For them, the Redeemable, a new approach which enables new opportunities must be given.

We should be under no illusions that the Criminal Justice System is now failing in its primary duty to keep the public safe. In protecting the public from the Wicked, the Criminal Justice System must be a bulwark against Thucydides’ assertion that the “strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”. For the majority who are Redeemable, the Criminal Justice System must also be, as Winston Churchill argued, a place where it is possible to find ‘the treasure in the heart of every man’.

Next chapterThe Policy Proposals

1. Sentencing reform

1.1. A mandatory sentence of imprisonment for the most prolific offenders on conviction

The vast majority of citizens and visitors to the United Kingdom follow the law and go about their lives without committing crime. However, there is a cohort of individuals who, through their particularly prolific campaigns of violence and criminality, cause their victims untold misery and prevent the public from being able to live safely in their homes and in their communities. There can be no doubt of the substantial harm these individuals cause.

5.89 million people were convicted of a criminal offence in the courts of England and Wales between 2000 and 2021. Of them, 243,000 are categorised as being ‘Adult Prolific Offenders’. On average these ‘Adult Prolific Offenders’ commit eight times as many offences per offender (20.13 offences) compared to non-prolific offenders (2.49 offences).62Ministry of Justice, Prolific Offenders: Update on the characteristics of prolific offenders, 2000-2021, link Although they represent only a small minority of offenders (only nine percent), prolific offenders receive nearly half of criminal sentences (10.5 million) and just over half of all convictions (52%).63Ibid They are most likely to have started their criminal career with convictions for theft (shoplifting) with many going on to commit very serious offences.64Ibid

| The ‘Adult Prolific Offender’ Cohort65Ibid |

| Analysis of the Police National Computer shows that between the years 2000 and 2021 there were 5.89 million individuals who were convicted or cautioned for a criminal offence in England and Wales.

The Ministry of Justice defines individuals as ‘Adult Prolific Offenders’ who are 21 years and older and have had a total of 16 or more previous convictions or cautions, with 8 or more convictions or cautions committed since the age of 21. Of those 5.89 million people, four percent of them (243,202 individuals) meet the definition of ‘Adult Prolific Offender’, as defined by the Ministry of Justice. They are overwhelmingly male (90.3%). Black people are over-represented in the cohort compared to the population as a whole (7.5% compared to four percent of the population) as are white people (88.6% compared to 81.8% of the population). Although they represent only a small minority of the offenders (9%), prolific offenders (both adult and juvenile offenders) represent nearly half of sentencing occasions – 10.5 million sentences and just over half of all convictions (52%). Prolific offenders overall commit 8 times as many offences per offender (20.13 offences) compared to non-prolific offenders (2.49 offences). |

Number of previous convictions for offenders cautioned or convicted for an ‘either-way’ offence (Year to December 2022)66Ministry of Justice, First time entrants (FTE) into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories: year ending December 2022, link

| The ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’ Cohort |

| Within the ‘Adult Prolific Offender’ group are a smaller group that we call ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’. These are individuals who have accumulated at least 45 previous convictions in their lifetime. Individuals falling into this category were convicted or cautioned of an ‘either-way’67‘Either-way’ offences are those which can either be tried ‘summarily’ in the Magistrates Court or on ‘indictment’ in the Crown Court. They include Burglary, Actual Bodily Harm or Possession With Intent to Supply Drugs or indictable offence on 9,668 occasions in the year to December 2022.68Ministry of Justice, First time entrants (FTE) into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories: year ending December 2022, link

Despite the astonishingly negative impact this relatively small group of individuals have in communities, on 52.7% of occasions they were not sentenced to a term of imprisonment.69Ibid Remarkably, despite already having at least 46 previous convictions 1.1% of ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ received a police caution and 6.9% are discharged on conviction without any substantive punishment.70Ibid |

| Type of Disposal on Conviction | ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’ Disposal (%)71For ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ for the Year to December 2022: Ministry of Justice, First time entrants (FTE) into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories: year ending December 2022, link |

| Caution | 1.1% |

| Absolute Discharge | 0.3% |

| Conditional Discharge | 6.6% |

| Fine | 13.3% |

| Community Penalty | 11.3% |

| Suspended Sentence | 10.7% |

| Immediate Custodial Sentence | 47.3% |

| Other | 0.4% |

| Case Study: A ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’

Name: Craig Nicholson72Chronicle Live, 23rd June 2023, link Location: Gateshead Date: June 2023 Offence: 9 charges of theft and 1 charge of attempted theft Previous convictions include: 343 previous convictions Sentence: 24 months community order, fined £100 and given a two-year Criminal Behaviour Order |

| Case Study: A ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’

Name: Warren Russell73IslandEcho, 12th December 2022, link Location: Isle of Wight Date: December 2022 Offence: 7 counts of theft Previous convictions include: 115 convictions, the majority of which are for shoplifting Sentence: 8 weeks imprisonment suspended for 12 months |

| Case Study: A ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’

Name: Carey Lyons74Belfast Telegraph, 19th February 2023, link Location: Belfast Date: February 2023 Offence: 15 charges of possessing indecent images of children – 359 indecent images of children and a further 160 ‘prohibited’ images. Previous convictions include: Almost 100 previous convictions over the last 50 years including indecent assaults on female and male children in 1973, previous convictions for possession of indecent images in 2000, 2005, 2013 and 2017; Breach of licence for sex offences and breaching the terms of a Sexual Offenders Prevention Order in 2008, 2018 and 2021 Sentence: Two and a half years imprisonment suspended for three years |

In every case these individuals have been through the Criminal Justice System on many occasions. The reasons and motivations behind their offending behaviour may well be complex, but it is the wider public and the victims of these offenders that are suffering as a result. A more robust approach to dealing with these most prolific offenders, which reflects the combined totality of their offending, is required.

To give the public a respite from the criminal behaviour of the most prolific offenders, a mandatory minimum term of two-years imprisonment for individuals who meet the threshold of becoming an Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offender’ should be applied on conviction.

Judges and Magistrates should be required to impose this mandatory minimum sentence, which must be served in its entirety in custody, without any option for early release. This term of imprisonment should be applied immediately on conviction with the sentence able to be given in both the Magistrates and Crown Courts.

In cases where a defendant is being convicted of multiple offences on a single occasion, only a single two-year term of imprisonment would be applied. In cases where a defendant is convicted of further offences when they are already serving a two-year sentence under this provision, a further sentence should not be applied.

The precise definition of the offenders who are to be included within this provision will require very careful and precise drafting by legislators.

A series of protections should be implemented to ensure that while this provision impacts the most prolific offenders it is balanced with maintaining appropriate levels of judicial independence and preventing wholly unjust outcomes.

Firstly, that while all previous criminal convictions obtained as an adult in the courts of England and Wales should ‘count’75This would not however include convictions which have not been obtained as a result of a court hearing – for example police cautions, Fixed Penalty Notices and other similar disposal mechanisms would be excluded. for the purposes of defining an individual’s previous offending in making them an Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific’ offender, only conviction for a further ‘either-way’ or indictable offence should trigger the provision.

Secondly, to prevent a wholly unjust outcome, any new provision for the most prolific offenders should reflect existing similar statutory provisions. Section 315 of the Sentencing Act 2020 provides that those convicted of repeated possession of offensive weapons and pointed or bladed articles should be sentenced to a minimum term of imprisonment, with those over the age of 21 years the term of imprisonment is six months.

| Section 315 Sentencing Act 202076Section 315 Sentencing Act 2020, link

(1) This section applies where— (a) an offender is convicted of an offence (the “index offence”) under— (i) section 1(1) of the Prevention of Crime Act 1953 (carrying offensive weapon without lawful authority or reasonable excuse), (ii) section 139(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 (having article with blade or point in public place), or (iii) section 139A(1) or (2) of that Act (having article with blade or point or offensive weapon on education premises), (b) the offence was committed on or after 17 July 2015, and (c) when the offence was committed, the offender— (i) was aged at least 16, and (ii) had at least one relevant conviction. (2) The court must impose an appropriate custodial sentence unless the court is of the opinion that there are particular circumstances which— (a) relate to the offence, to the previous offence or to the offender, and (b) would make it unjust to do so in all the circumstances. |

Over the last 7 years, in around a third of these cases related to repeated possession of an offensive weapon or bladed article, Judges and Magistrates have elected not to imprison the defendant.77Ministry of Justice, Knife and Offensive Weapon Sentencing Statistics: January to March 2023, link This is expressly permitted under the legislation and acts as a barrier to ensure that defendants are not imprisoned in cases where it would be wholly unjust. A similar approach should be taken in relation to the mandatory imprisonment of Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific’ offenders under any new sentencing provision.

| Year Ending | Absolute/ Conditional Discharge

(%) |

Fine

(%) |

Community Penalty

(%) |

Suspended Sentence

(%) |

Immediate Custody

(%) |

Other

(%) |

| 2017 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 21 | 67 | 3 |

| 2018 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 70 | 4 |

| 2019 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 18 | 72 | 3 |

| 2020 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 18 | 72 | 3 |

| 2021 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 66 | 3 |

| 2022 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 22 | 64 | 4 |

| 2023 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 23 | 64 | 6 |

While imprisoning the most prolific offenders for a minimum period may well bring a period of respite from their offending behaviour for the public, it is essential that during this time other potential benefits are realised. Up to 50% of the prison population are believed to be functionally illiterate78HM Inspectorate of Prisons & OFSTED, Prison education: a review of reading education in prisons, 22nd March 2022, link and 50% are believed to be addicted to drugs.79Ministry of Justice, Press release, ‘Addiction crackdown sees huge rise in prisoners getting clean’, 10th February 2023, link Both factors are heavily weighted to the most prolific offenders.

During their two-year mandatory prison sentence period it is essential that prisoners are not merely warehoused away from society. They must be given every possible opportunity to access the services and opportunities which are known to reduce the likelihood of reoffending on release. At a minimum, for those that require them, prisoners must have access to drug and alcohol addiction treatment services and access to education and skills development opportunities.

Prolific offenders are clearly at high risk of reoffending on release without appropriate interventions being utilised during their time in custody. Prison and probation leaders must therefore be required by law, and then held to account, for delivering these services to this particular prison population. This two-year sentence must be used as an opportunity to break the cycle of reoffending for these offenders once and for all.

Recommendation: The Government must introduce legislation that requires Magistrates (extending the existing sentencing powers for Magistrates) and Crown Court Judges to sentence Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ to a minimum term of imprisonment of two years in custody on conviction for any further ‘either-way’ or indictable criminal offences.

Recommendation: For Adult ‘Hyper-Prolific Offenders’ sentenced to a minimum term of imprisonment, legislation should be introduced which places obligations on His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service that these offenders receive a ‘Mandatory Individual Intervention Plan’ for the duration of their time in custody (for example including mandatory drug addiction treatment, education or skills programmes).

1.2 An expansion of ‘Deferred Prosecution’ programmes for non-violent and non-prolific offenders

There is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that alternatives to formal prosecution may, for some offenders, lead to reduced offending, be more cost effective and maintain the confidence of victims and the public. By dealing with offenders outside of the courts system this could also have the effect of substantially reducing the flow of cases to the Crown Prosecution Service and through into the criminal courts in order that the formal Criminal Justice System can focus on more serious offending and prolific offenders.

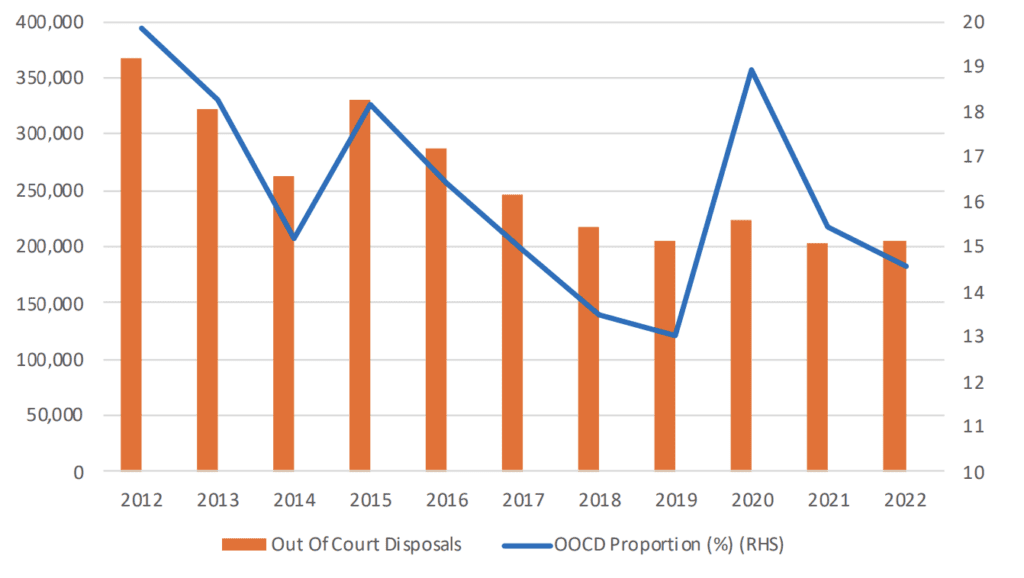

Their use however has been progressively decreasing over the last decade. In 2012 there were 368,043 Out Of Court Disposals (OOCDs) issued by police in England and Wales, representing 19.9% of offenders who were prosecuted or dealt with by OOCD.80Ministry of Justice, Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly: December 2022, link By 2022 that number had reduced to 204,289 OOCDs, representing 14.6% of those prosecuted or dealt with by OOCD.81Ibid

The number of and proportion of offences dealt with by Out Of Court Disposals in England and Wales (2012 to 2022)82Ibid

One of the most promising forms of ‘Out Of Court Disposal’ appears to be the use of ‘Deferred Prosecutions’. Under these arrangements, once the police have completed an investigation, under a ‘Deferred Prosecution’ the police pause a prosecution if the offender agrees to undergo a series of diversionary or restorative activities, which if successfully completed results in ‘no further action’ being taken against them.

Under the Metropolitan Police’s Turning Point programme, which has been operating in North-West London since 2017, lower-harm non-prolific offenders who, based on their offence and any previous offending were unlikely have incurred a custodial sentence (based on the relevant Sentencing Guidelines) were offered a four-month police-supervised contract as an alternative to immediate prosecution.83K. Harber & E. Neyroud (2022), Turning Point (NW London): Interim Findings Report These contracts applied a range of potential conditions with a focus on making restoration to victims, rehabilitative activities and conditions to prohibit certain activities. These are tailored to tackle the individual’s root causes of offending and to make restoration to the victim. Offenders’ compliance with the conditions were overseen by an offender manager.

To be eligible offenders must meet strict criteria – only those who had committed less serious offences and those who were not repeat offenders were eligible. Some types of offending were automatically excluded from the programme, including sexual offences against children, partner domestic abuse and the use of a firearm, knife or weapon. Unlike all other out-of-court disposals, eligibility for the programme does not require a formal admission of guilt. Successful completion of the conditions of the contract result in ‘no further action’ being taken, and therefore no criminal record for the offender. Those who declined to participate, failed to adhere to the contract conditions or continued to offend were immediately prosecuted for the original offence.

Initial results from young people joining the programme went on to receive 58% fewer criminal charges than those who were charged or received a police caution – a significant reduction in the likelihood of reoffending. Notably there was no detrimental impact on victim satisfaction. A predecessor programme in the West Midlands showed a reduction of harmful reoffending by 36%.84Ibid

The sense that ‘Deferred Prosecutions’ are in some way a ‘soft on crime’ option appears to be without merit. Remarkably, the conditions which offenders are required to abide can be so stringent that some 19.5% of those offered the ‘Deferred Prosecution’ option declined because they felt that the conditions were more stringent that anything a court might apply on conviction.85Ibid

The theoretical basic for using ‘Out Of Court Disposals’ is based on Deterrence theory: certainty (that a suspect will be caught and punishment imposed), celerity (that it will be imposed quickly) and severity (that it will be serious enough to put off other potential offenders).86J. Abramovaite, S. Bandyopadhyay, S. Bhattacharya, & N. Cowen (2023), Classical deterrence theory revisited: An empirical analysis of Police Force Areas in England and Wales, European Journal of Criminology, 20(5), pp. 1663-1680, link ‘Deferred Prosecutions’ have the potential to contribute to all three in a way that currently some traditional prosecutions, with the potential delays in obtaining charging decisions from the Crown Prosecution Service and uncertain sentencing decisions with magistrates, may well not.

Of the 43 territorial ‘Home Office’ police forces of England and Wales only a small number have ‘Deferred Prosecution’ programmes operating. A key barrier to increased adoption appears to be that where offences are successfully dealt with through ‘Deferred Prosecution’ the crime is not formally recorded as having been ‘solved’.87The offence is recorded under Home Office Counting Rule (HOCR) ‘Outcome 22’ noting that formal sanction is not appropriate because diversionary activity has been undertaken. This simple change could lead to the approach being more attractive to police forces.

The level of investment to expand the roll-out of ‘Deferred Prosecution’ would be moderate (estimated at an annual spend of £10 million for expansion across London) and could be offset by a far more significant saving to the courts budget by the programmes’ widespread roll-out.

Recommendation: ‘Deferred Prosecution’ programmes should be expanded to all force areas under a consistent framework with an amendment to the Home Office Counting Rules so crimes which are dealt with through ‘Deferred Prosecution’ can be shown as having been ‘solved’.

1.3 Expanding the use of non-custodial sentences for non-violent offenders making them more consequential as an alternative to short-term prison sentences

There is substantial evidence which indicates that community-based punishments are associated with a lower likelihood of offenders reoffending on release compared to similar offenders who receive short-term prison sentences (those sentences of less than 12 months in custody).88G. Eaton & A. Mews (2019), The impact of short custodial sentences, community orders and suspended sentence orders on reoffending, Ministry of Justice, link For offenders who had started a community order (including suspended sentences) in the most recent period for which data is available, the proven reoffending rate was 30.6%.89Ministry of Justice, Proven Reoffending Statistics Quarterly Bulletin, July to September 2021, link For those who had served a short sentence of less than 12 months the rate was far higher, at 55.1%.90Ibid Overall, 25% of offenders were convicted of reoffending within 12 months.91Ibid The proven rate of reoffending over the last decade has been fairly stable, fluctuating between 22.7% and 30.6% since 2010.92Ibid Perhaps unsurprisingly, the more previous convictions a prisoner has, the more likely they are to then be reconvicted.93Ibid

In addition to reducing the risk of reoffending there are also substantial potential financial benefits to an increase in community-based penalties. Prisons expenditure is estimated by the Ministry of Justice at £47,434 per prisoner per year,94Ministry of Justice, Costs per place and costs per prisoner by individual prison, 9th March 2023, link while the average annual cost to supervise an individual in the community is only £3,550 per person (based on 2018/19 data).95N. Mutebi & R. Brown (2023), The use of short prison sentences in England and Wales, 27th July 2023, UK Parliament, link There have been numerous previous efforts to reduce the number of short sentences, most recently in 2019.96Ministry of Justice (2019), Smarter sentences, safer streets: David Gauke speech, link Given the wealth of evidence available relating to short sentences and their alternatives, that these efforts faltered is deeply unfortunate.

| Types of Sentence |

| The Sentencing Council for England and Wales sets guidelines for the courts to follow in determining the sentence for a convicted offender. The main sentencing options are:

Absolute Discharge: No further action is taken, although the offender will receive a criminal record. Conditional Discharge: No further action is taken, unless a further offence is committed by the offender during a specified period of time determined by the court (less than three years). If they reoffend during the specified time period they can also be sentenced for the original offence. An offender receives a criminal record. Fine: Magistrates Courts can apply a fine of up to £5,000. The Crown Courts can levy an unlimited fine. An offender receives a criminal record. Community sentences: A series of activities which an offender is required to undertake, under supervision from the Probation Service, following conviction. An offender receives a criminal record. Should the offender breach the conditions of the sentence various sanctions can apply, including resentencing the offender or applying additional conditions. Suspended Imprisonment: The Judge or Magistrate has determined that the threshold for a custodial sentence has been reached, but has also decided that the offender should be given the opportunity to serve the sentence in the community. The same conditions as those used for community sentences can be applied. Should the offender breach the conditions of the sentence the suspension can be revoked and the offender be sent to custody. An offender receives a criminal record. Immediate Imprisonment: The sentence imposed by the court represents the maximum amount of time that the offender will remain in custody. In most cases they may be entitled to be released on ‘licence’ from prison part-way through their sentence to serve the remainder in the community. An offender receives a criminal record. |

That an individual may be more likely to reoffend is not on its own sufficient reason for short-term prison sentences not to be applied in appropriate cases. Section 57 of the Sentencing Act 2020 sets out the purpose of sentencing an adult offender once they have been found guilty of a criminal offence by a court of law.97Section 57, Sentencing Act 2000, link These are:

- the punishment of offenders;

- the reduction of crime (including its reduction by deterrence);

- the reform and rehabilitation of offenders;

- the protection of the public; and

- the making of reparations by offenders to persons affected by their offences.

It is entirely legitimate for individuals who have been convicted of criminal offences to be sentenced to a term of imprisonment for reasons of punishment or to protect the public. This is particularly the case for those convicted of offences of violence, sex offenders and individuals who are prolific offenders. However, wherever possible for non-violent and non-prolific offenders, given the reduced likelihood of future reoffending and the substantial potential cost savings, community-based penalties should in most cases be the favoured option.

Key to retaining public confidence in community-based penalties is that they must not be seen as a ‘soft’ option – the consequences for offenders must be significant, with those consequences also contributing to offenders being less likely to offend in the future rather than more likely. The penalty for breaching a community-based sentence must be severe.

| Types of Community Sentences |

There are thirteen conditions which can be applied to a Community Sentence on conviction:

|

Despite their potential effectiveness in reducing reoffending and the considerable cost savings compared to sentencing someone to prison, the proportion of offenders being sentenced to community penalties has fallen substantially. Over the last decade the proportion sentenced to a community-based penalty has fallen from 12.3% of offenders in the year to December 2012 to 6.6% in the year to December 2022.98Ministry of Justice, Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly: December 2022, link

The proportion of offenders sentenced to a community sentence, immediate custody or a suspended sentence (2012 – 2022)99Ibid

Although at the end of March 2023 only 5.3% of all non-remand prisoners were in custody for short-term sentences (less than 12 months) some 69.6% of non-remand prisoners arriving in prison in the year to March 2023 had been sentenced to short-term sentences (less than 12 months).100Ministry of Justice, Offender Management statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, link This suggests that while those receiving short-term sentences make up a small minority of the prison population, they make-up a significant proportion of the turnover of those entering and leaving prison.

Given the apparent financial and rehabilitative benefits of community-based sentences, there would be value in reversing their declining trend for non-violent offenders. This would also require a substantial improvement in the ability of the Probation Service to deliver the necessary levels of supervision of offenders in the community.

Recommendation: The Government should seek to expand the use of non-custodial sentences for non-violent offenders as an alternative to short-term prison sentences while also making community sentences more consequential for offenders. This should include setting out in legislation that:

- There should be a presumption in favour of community-based sentences rather than short-term prison sentences for non-violent and non-prolific offenders.

- When sentencing offenders to a community-based sentence Judges and Magistrates should be required to outline in detail which conditions they are applying and which conditions they are not, and for each why they have made that decision: When applying a community-based sentence to a convicted offender, Magistrates and Judges must consider the full range of punitive, rehabilitative and restorative options available. As part of the sentencing hearing in court Judges and Magistrates must be required to articulate, in relation to each of the 13 possible requirements for a community-based punishment, whether they are applying that condition or not and why they have made such a decision. There should be a presumption in favour of applying any conditions which would likely contribute to reducing the likelihood of those convicted from offending again in the future. There should be a presumption that cases offenders are subject to electronic monitoring.

- In all cases where a suspended sentence is given community-order type conditions should also be applied: All suspended sentences should have conditions applied from the options available for community-based sentences.

- The amount of time which can be applied to unpaid work requirements be expanded: Currently the maximum number of hours of unpaid work is 300 hours to be completed within 12 months. This should be doubled to 600 hours – by increasing the punitive elements of community-based sentences this will widen the band of offenders who are eligible for them rather than short-term sentences.

- Home Detention Curfews should be expanded for non-violent prisoners who have served the vast majority of their sentence, with the remainder to be served in the community. Currently prisoners serving a sentence of four years or less may be eligible to spend their last 180 days under a curfew at a suitable and verified address. This should be extended to appropriate prisoners serving longer sentences.

2. Swift justice

2.1 Stripping away unnecessary barriers to swiftly charging prolific offenders

The impact of excessive delays within the Criminal Justice System is considerable. Public safety is compromised while those guilty of offences remain in our communities rather than in custody. Victims often report being unable to move on in the aftermath of an offence, until their case has been heard in court.101P. Rosetti (2015), Waiting for Justice: how victims of crime are waiting longer than ever for criminal trials, Victim Support, link For defendants seeking to clear their name they have the spectre of a trial hanging over them, potentially for many months and years. Changes in recent years, to how decisions are reached on whether to charge suspects are leading to all of these outcomes.

In most cases in England and Wales the police are responsible for conducting criminal investigations and the Crown Prosecution Service is responsible for their prosecution. Decisions about whether to prosecute suspects in the simplest of cases can be made by the police, and in anything other than the simplest of cases charging decisions generally reside with the Crown Prosecution Service.

The process to be followed by Crown Prosecutors in making charging decisions is outlined in the ‘Charging (The Director’s Guidance) – sixth edition’102Charging (The Director’s Guidance) – sixth edition, December 2020, issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions under the provisions of section 37A of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, link often referred to as ‘DG6’. Crown Prosecutors are required to make a decision based on either the Full Code Test, where all of the relevant evidence and material has been collected by the police, or the Threshold Test, where there is still evidence or material to be collected but there are circumstances which mean that the Crown Prosecutor must make a decision at an earlier stage.

| Full Code Test |

Stage 1: The Evidential StageIs there enough evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction against each suspect on each charge? Considering the evidence and material as a whole is it more likely that a court or jury would convict the defendant of the charge after hearing the evidence, or that they would acquit them? If the Evidential Stage is met then the prosecutor must move on to Stage Two. Stage 2: Public Interest StageIs it in the public interest for each individual on each charge to be prosecuted? The prosecutor must balance the factors for and against prosecution carefully and fairly. The factors that may affect the decision include: – seriousness of the offence; – suspect’s level of culpability; – circumstances of and harm caused to the victim; – if the suspect is under 18 at the time of the offence; – impact on the community; – whether prosecution is a proportionate response; and – whether sources of information or national security could be harmed. |

| Threshold Test |

| Where a suspect currently in police custody presents a substantial risk if they were released, but not all of the evidence is yet available, a prosecutor can make a preliminary assessment of the evidence under the Threshold Test.

There are strict criteria for applying the Threshold Test, all of which must be met: 1. Insufficient evidence is currently available to apply the evidential stage of the Full Code Test. 2. There are reasonable grounds to believe that further evidence will become available. 3. The seriousness or circumstances of the case justify making an immediate charging decision. 4. There are substantial grounds under the Bail Act 1976103Under the Bail Act 1976 under normal circumstances a person may only be denied bail if there are substantial grounds for believing that a defendant would fail to surrender to custody, commit further offences, interfere with witnesses or obstruct the courts of justice. to detain the suspect in custody after charge and an application to withhold bail can properly be made at court by a prosecutor. When considering the evidence under the Threshold Test, the prosecutor must establish if there is a reasonable suspicion that the suspect has committed the offence and whether further evidence can be obtained to provide a realistic prospect of conviction. The public interest test must also be met. |

During the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, in order to manage the flow of cases into their systems, the Crown Prosecution introduced an ‘Interim CPS Charging Protocol – Covid-19 crisis response’.104Crown Prosecution Service, Interim CPS Charging Protocol – Covid-19 crisis response, link

Historically, where the suspect was:

- in police custody, and

- suitable to be bailed (so the Threshold Test as outlined above was therefore not applicable), and

- the police had completed their investigation,

- the Crown Prosecution Service would consider there and then whether the suspect should be charged or not under the ‘Full Code Test’.

Under the Transforming Summary Justice protocols, introduced in June 2015, the suspect would then be bailed for their first appearance at Magistrates Court within 14 days for those anticipated to be pleading guilty and 28 days for those anticipated to be pleading not guilty.105Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate, Transforming Summary Justice: An early perspective of the CPS contribution, February 2016, link Historically, under previous arrangements, it was even possible for suspects to be bailed from the police station having been charged to appear at their first Magistrates Court hearing within a week.

The Crown Prosecution Service’s Interim Covid-19 Protocol however now requires that in all cases that, unless the suspect is suitable to be dealt with under the Threshold Test, the suspect be bailed for a minimum of 28 days in order that a prosecutor’s advice can be obtained.106Crown Prosecution Service, Interim CPS Charging Protocol – Covid-19 crisis response, link Once the advice is obtained and the suspect charged they must then be bailed to Magistrates Court for 14 days for an anticipated guilty plea and 28 days for an anticipated not guilty plea. As a result this has extended the timescales for a suspect’s first appearance at Magistrates Court to a minimum of 42 days for a guilty plea and 56 days for a not guilty plea.

The overall result of the change in how the CPS approach charging decisions means that while under historic regimes suspects could be charged and appear in court within a week, now the same suspect may well not appear in court for over two months or more.

Indefensibly, as of August 2023, some two years after almost all legal limits on social contact were removed the Crown Prosecution Service continued to use the ‘Interim CPS Charging Protocol’. The average time the Crown Prosecution Service takes to charge suspects from first receiving the case file from the police has increased substantially over recent years. 107The average timeliness of the decision to charge is a calculation of the average number of calendar days elapsed between the first submission of a case by the police, to the date on which the last decision was made to charge. In the quarter to June 2019 Crown Prosecution Service took 27.31 days from receiving the case file to deciding to charge, increasing to 43.76 days in the quarter to March 2023 – an increase of 60.2% over the period.108Crown Prosecution Service, Quarterly Data Summaries, link Even for cases where victims are at most risk, domestic abuse cases, the length of time to charge suspects has increased. In the quarter to June 2019 this was 12.02 days, increasing to 24.8 days for the quarter to March 2023. This increase of 106.3%, more than doubling the time it takes to charge domestic abuse suspects, represents nothing less than an utterly abysmal failure on the part of prosecuting authorities.109Ibid

Average number of days from the police first providing a case file to the Crown Prosecution Service to the date the Crown Prosecution Service decide to charge the suspect (England & Wales by quarter)110Ibid

The impact of continuing to apply protocols introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic has been substantial – on the swiftness of justice for victims, suspects and the public. The Crown Prosecution Service is in the process of updating its charging protocol, but is intending to retain the system of bailing most cases to obtain charging advice. In doing so the Crown Prosecution is delaying justice, increasing the likelihood that victims and witnesses disengage from the court process, and increasing the potential for reoffending by suspects and putting the public at risk. It must be reversed for all offenders.

The approach of the Crown Prosecution Service is particular egregious when it comes to the most prolific offenders. The classic theory of deterrence, how potential offenders are deterred from committing crime, is centred around three factors – certainty (the likelihood of the offender being caught), severity (the seriousness of the punishment) and celerity (the speed of punishment being applied).111J. Abramovaite, S. Bandyopadhyay, S. Bhattacharya, & N. Cowen (2023), Classical deterrence theory revisited: An empirical analysis of Police Force Areas in England and Wales, European Journal of Criminology, 20(5), pp. 1663-1680, link Prolific offenders have repeatedly demonstrated that they are unable or unwilling to abide by the rules set down by our society and every possible effort must be made to deter them in the future.

By slowing down the process the Crown Prosecution Service is at the very least working counter to the ‘celerity’element of deterrence. To counter this the Crown Prosecution Service, and if necessary the Government by amending the Bail Act 1976, should in all cases consider the evidence as to whether to charge a suspect for Prolific Adult Offenders under the Threshold Test. This would ensure that these offenders are dealt with in as expeditious a manner as possible and in so doing ensure that the public are appropriately protected.

While the Crown Prosecution Service have performed increasingly poorly over recent years responsibility for the delays in the timeliness of cases being charged does not solely rest on their shoulders. It has been a long-standing concern that the quality of case files prepared by the police are often far below the standard required. While many efforts to improve case file quality over the years have certainly increased the bureaucratic burden on individual officers and prosecutors it is difficult to conclude that this has solved the actual problem –widespread poor quality case file preparation by officers. This is a significant issue which chief constables must take seriously.

Recommendation: In all cases where the suspect is a prolific offender the Crown Prosecution Service should review the evidence under the Threshold Test – if necessary the Government should amend the Bail Act 1976 to enable this.

Recommendation: In all cases which are ready to be reviewed under the Full Code Test the Crown Prosecution Service must revert to providing in-custody charging advice.

Recommendation: For non-complex cases where the suspect is not in custody or is on bail the timescale for the Crown Prosecution Service to provide advice should be reduced from 28 days to 7 days. The new Director of Public Prosecutions should be held to account for achieving this within one year of his term of office commencing, on the 1st November 2023.

2.2 Expanding sentencing powers for Magistrates and District Judges to deal with offenders more swiftly and contribute to reducing the Crown Court backlog.

The vast majority of criminal cases are heard in the Magistrates’ Courts. Magistrates’ Courts are, in the main, able to deal with cases far more quickly than Crown Courts. There is, however, a constant need to balance efficiency and speed with quality of justice and the opportunity for a defendant to have their case heard by a jury – something only possible in the Crown Court.

| Types of Offences |

| Summary Only: The lowest severity of offences, including most driving offences and very low-level assaults. These offences can only be tried in the Magistrates Court

Either-Way: Offences which cover a wide range of crimes including Actual Bodily Harm, theft and possession of drugs. They can be tried at either the Magistrates Court or Crown Court, depending on the specific circumstances of the offence. Magistrates assess the case and determine if their sentencing powers are likely to be sufficient. If they are sufficient the case is allocated to the Magistrates Court; if not the case will be allocated to the Crown Court. Defendants can also elect for their case to be sent to Crown Court for trial in front of a jury. Indictable Only: The most serious offences, including murder, manslaughter, rape and robbery. These offences can only be tried in the Crown Court. |