Authors

Content

Foreword

Peter Clarke

Senior Fellow, Policy Exchange

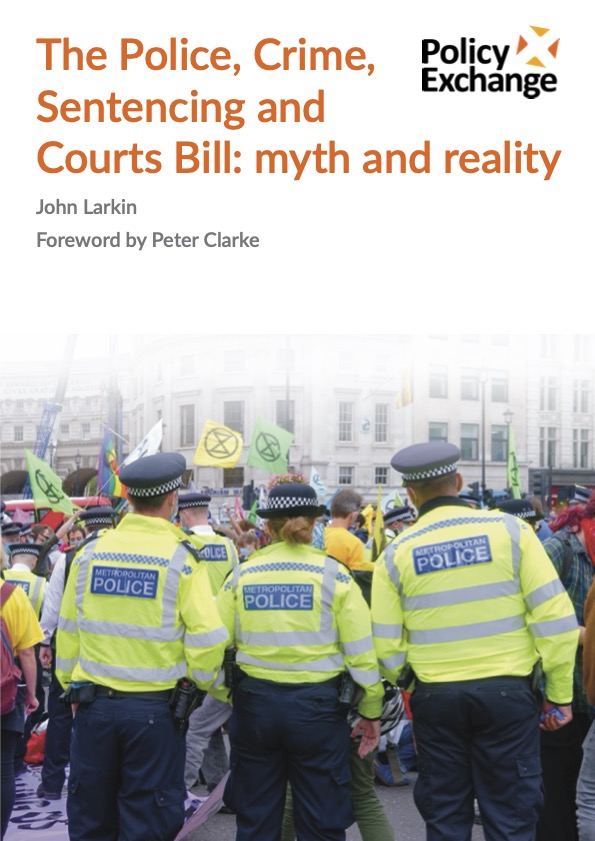

Are the rights of protesters and the rights of all other citizens fairly balanced? Think back to the Extinction Rebellion protests of April 2019, when climate activists chose to “peacefully occupy the centres of power and shut them down”, as they put it, including the heart of London.

The protests, organised globally, were perhaps the most disruptive in history. A small number of people managed to stop hundreds of thousands more going about their daily lives. They could not get to work, see family and friends or go shopping, because the streets were blocked by an extensive series of roadblocks and other tactics. At one point printing presses were stopped, undermining the free press. There was a huge economic hit to the capital, as transport hubs were closed and commuting became almost impossible.

As a former senior officer in the Metropolitan Police, I felt for my former colleagues as they struggled to contain the chaos. The protestors were well organised and ingeniously disruptive. They climbed on to bamboo towers several metres above the road surface, making it very difficult to remove them without risking their safety. They attached themselves to buildings. Dozens would “go floppy” in the middle of the road at the same time, making it difficult to arrest and carry them away. What is more, they were highly agile. Remove one group and end a five-mile tailback and the call would go out on social media. Replacements would soon arrive.

What were police to do? Was the legislation clear enough about their powers? And is it clear enough two years later when, for example, a one-man protest with an amplifier can stop hundreds of civil servants from getting on with their jobs in the heart of Whitehall? The Government thinks not, which is why the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill is currently making its way through Parliament.

To me, despite the “Kill the Bill” protests and challenges from civil liberties groups, the Bill contains welcome new measures. We must always be on guard against new laws that might limit our ability to assemble and peacefully protest; the right to continue doing so is vital to democracy (and enshrined in the ECHR, though it predates that in English law by centuries). However, as John Larkin, makes clear in a new paper for Policy Exchange, this Bill is certainly not some instrument of repression as its opponents suggest.

What it does do is recognise that the methods of protest are evolving and therefore so must policing tactics in response – and the legislation that backs them up. The Bill, for instance, will add a clause making “noise which may result in serious disruption to an organisation in the vicinity” unlawful, if it causes serious unease in the affected party. This has caused alarm among campaigners, but they overlook the good reasons, which Larkin makes clear, why in practice these clauses are likely to be interpreted compatibly with the ECHR and existing law. Protesters will not be silenced because of what they are saying but how they are going about it – we may see fewer Glastonbury Festival-style stages on Parliament Square, with a few hundred people causing severe disruption to tens of thousands in the vicinity.

Similarly, there are complaints about the legislation giving greater scope to prosecute protesters for damage to property, serious annoyance or serious inconvenience – which could in theory lead to maximum sentences of 10 years. Once again, however, this overlooks existing legislation that would temper the application of severe sentencing.

As robust debate on this and other measures in the Bill continues, and MPs test ministers on this new legislation in Parliament, two principles should be upheld. The ability to assemble and protest peacefully must be protected as a fundamentally important right. I believe the Bill achieves this. Secondly, significantly more protection must be given to the rights of all other citizens to go about their daily lives without suffering disproportionate and severe levels of disruption. Protesters will often believe wholeheartedly that this disruption is justified for their particular cause; ultimately, the law must correct this misapprehension, for the benefit of us all.

Next chapterIntroduction

This paper examines some of the criticisms offered against part 3 of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. It finds, in summary, that most of these are misplaced or overblown. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill can certainly be improved and even if it does not prove, if enacted, to be the boon hoped for, it is certainly not the dark instrument of repression conjured up to alarm us.

Part 3 of the PCSC Bill has four principal effects: a) It introduces a new basis upon which the police can lawfully impose conditions on public processions and assemblies and, for the first time, on one-person protests; b) It amends existing offences of failing to comply with conditions imposed by the police, making it easier to convict someone of the offences and increasing the maximum penalties available; c) It expands the controlled area around Parliament and provides a new power to the police to prevent the obstruction of vehicular access to the Parliamentary Estate; and d) It creates a statutory offence of public nuisance to replace the existing common law offence. The focus below on (b) and (d) concludes, with one exception that the text of the Bill stands up to scrutiny.

In our political and constitutional culture a civilian police force works with protestors so that the point of a protest can be made effectively and safely. Despite media tags, there are no such people as ‘riot police’ in the United Kingdom. Managing protest has always relied on communication and shared expectations between police, protestors, the wider public, in a framework set by Parliament and democratically accountable Government.

Traditionally, protest organisers would – and still do – discuss arrangements with the police, and on most occasions everything would pass off peacefully. If there was a refusal to negotiate, or violence broke out, then the police would enforce the law and could rely on political support in the aftermath. This understanding of how things should work has come under serious strain, and not just because of the complications caused by the Coronavirus regulations. It is a pre-pandemic problem that has been brought into sharper relief by recent events.

The Extinction Rebellion and other protests caused massive disruption and economic damage to our capital city. Livelihoods were disrupted for days and weeks on end. The protesters claimed that the importance of their cause justified breaking the law and disrupting others’ lives. In simple terms, they claimed the ends justified the means. Novel and highly disruptive tactics were used such as going ‘floppy’ or fixing themselves to buildings. These were deliberately designed to thwart police operations and the rights of other citizens were effectively cast aside.

The police themselves have for some time believed that they are hemmed in by legal uncertainty as to the constraints on the tactics they can use to enforce the law and minimise disruption. Meanwhile the public find it hard to understand how a protester sitting on a frame a few feet above the ground can be allowed to block a major street for hours on end.

The Bill has been attacked because, it is said, it will somehow prevent ‘peaceful’ protest or assembly. But even if it is ‘peaceful’ to bring major cities to a standstill, close transport hubs and disrupt the lives of countless thousands of fellow citizens, Parliament is entitled on behalf of us all to ask whether it is right to do so. The damage to individuals, business and the infrastructure of our country has been and will continue to be immense if ‘peaceful’ protest can always trump the interests of the wider community.

Lord Blair is surely right when he says in a recent interview, “I think it’s going to have to be very carefully drawn up as a piece of legislation, because the right to protest is absolutely vital,… “Now, all protests – you just have to look at the word – are going to irritate somebody, aren’t they? There are some issues there that need a bit of careful thinking.”1 Anoosh Chakelian Former Met Chief Ian Blair: The Tories are “much more disengaged” from Policing New Statesman 30 June 2021 Former Met chief Ian Blair: The Tories are “much more disengaged” from policing (newstatesman.com)

Careful thinking is always necessary.

Meanwhile, the sinister ambiguity of the ‘Kill the Bill’ slogan should not be ignored. The police have come under attack, both physical and verbal, from all sides. Political support has been patchy. The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police has said that they are faced with ‘fiendishly difficult’ decisions. There is a real risk that unless the Bill brings some clarity, those decisions will not be merely ‘fiendishly difficult’, but well nigh impossible. That will be in nobody’s interests – least of all those who want to stage a genuinely peaceful protest about an issue close to their hearts.

Next chapterMyth and Reality

Enactment of Part 3 of the Bill will not bring peaceful protest to an end. The provisions – still, of course to be debated, and, with luck, improved – provide for a re-balancing of the interests of those who wish to protest and the rest of the community. My desire to protest, and my undoubted right to protest, do not carry with them a right – and should not have the effect – of seriously burdening and disrupting the lives and conduct of my fellow citizens during the currency of my protest.

There are, of course, people who do believe that a right to protest (or, at least, their right to protest) carries with it the right to impose “serious unease, alarm or distress” on those who, less enlightened than the protester, wish to pick up their children from school, bring shopping to an elderly relative or meet a friend for coffee.

Those who do take that view can point to historical instances of political change achieved by protest. But, in doing so, they almost always confuse the changed view now taken of such protest (the Suffragettes are a good example) with how the sought-for change was achieved. Being beastly to Mr Asquith (even if viewed more benignly now than in 1911) did not change the franchise; that was the (later) work of Parliament.

Protesters who think they know better than the rest of us and who believe with a fervour that is in no way aligned to good judgement that their right to protest trumps our right to carry on lives without “serious unease, alarm or distress” also believe, or appear to believe, that the law should yield to them.

Our constitution may be said to have as foundational principle that Parliament doesn’t always get it right, which is why one Parliament cannot bind its successors. For most of us fallible creatures there is something both natural and reassuring in this principle. Our life as a political community is part of an inter-generational exercise in parliamentary trial and error. An aspect of that shared life is an acceptance that we may be wrong and others may be right and that it may be difficult from time to tell on which side right lies.

In what follows analysis is given of some of the critiques so far offered on Part 3 of the Bill. Many of these critiques have much in common and, so far as practicable, criticisms which may be made more than one body are addressed here only once.

What the critiques all have in common is a reliance on Articles 10 and 11 of the ECHR. It is always helpful to have these texts in mind when assessing some of the claims based on them, few of which possess any obvious anchoring in the text themselves, and not all of which find support in the glosses produced by the Strasbourg Court.

Article 10 provides: 1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises. 2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

Article 11 provides: “1. Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests. 2. No restrictions shall be placed on the exercise of these rights other than such as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. This article shall not prevent the imposition of lawful restrictions on the exercise of these rights by members of the armed forces, of the police or of the administration of the State.”

Next chapterThe JUSTICE Critique

Sections 12 and 14 of the Public Order Act 1986 permit a senior police officer to impose conditions on public processions and assemblies if she/he reasonably believes they may result in serious public disorder, serious damage to property or serious disruption to the life of the community. By Clauses 54 and 55 of the Bill “noise which may result in serious disruption to an organisation in the vicinity” and “noise which will have a relevant and significant impact on persons in the vicinity” will be added. Under these clauses, noise may be judged to have a significant impact on a person in the vicinity if, among other things, it may cause persons of reasonable firmness to suffer serious unease.

JUSTICE says that “Conditions which are imposed because they may cause a person serious unease risk breaching Article 10 ECHR. This is because Article 10 ECHR protects not only popular ideas and opinions but also those which, “offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.”2 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [20] (footnote omitted)

This criticism is misplaced. Setting aside the generalised assertion of risk (there are few public order measures of which it may not be said that there are ECHR risks – what matters is the likelihood of ECHR breach) the criticism ignores three factors. The first is that a power to impose a condition in respect of noise that may cause persons of reasonable firmness to suffer serious unease is unconnected with the nature of the ideas and opinions that protesters seek to express. That a person of reasonable firmness may be offended, shocked or disturbed by what is said will not permit the imposition of conditions; it is only if noise unconnected with content may have that effect that conditions may be imposed. Second, the likelihood that the power will be interpreted in this limited way is supported by the principle of legality, which justifies a presumption that Parliament does not intend to restrict free speech or assembly. This is reinforced in turn by section 3 of the Human Rights Act, which provides further assurance that the clauses, if enacted, are likely to be interpreted compatibly with the ECHR. It is (rightly) not suggested by JUSTICE that the clauses in question are incapable of being interpreted compatibly with the ECHR.

In the context of Article 11 ECHR JUSTICE says, “Protests tend to be noisy and are often meant to be challenging. People who disagree with the cause of a protest may well feel serious unease by the noise generated by it. In a democracy, this unease must be tolerated.”3 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [21]

As noted above, it is not the cause or message that justifies the imposition of conditions, and the test for their imposition is not subjective. If a person feels serious unease because of her or his dislike of the content of a deafeningly shouted message that serious unease will not justify the imposition of conditions; it will only be if the noise – setting aside the message – may cause persons of reasonable firmness to suffer serious unease that conditions may be imposed. Neither Article 10 nor Article 11 ECHR contains a right to deploy noise so as to cause serious unease to others.

It is right to be circumspect about giving Ministers wide powers to amend primary legislation but, in commenting on clauses 54(4) and 55(6) of the Bill (which give power to make regulations about the meaning of serious disruption to the activities of an organisation or to the life of the community, JUSTICE says it is “alarmed at another example, which forms part of an increasing trend, of using Henry VIII clauses in important pieces of legislation.”4 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [24]

JUSTICE may not be right about such an ‘increasing trend’ but, even if it is, clauses 54(4) and 55(6) cannot be regarded as forming part of such a trend, for these provision appear to permit one of the classic functions of subordinate legislation; that of filling in the detail. JUSTICE is entirely right to point to the need for Government to be “clear and upfront in defining the scope of such powers”5 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [24]

but there is no real reason to suppose that it will not be. There is value in the JUSTICE suggestion that these “powers should be limited in temporal scope by way of a sunset clause”6 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [24]

provided that duration is sufficiently long to permit use of the power to be informed by significant operational experience.

Clause 59 of the Bill replaces the common law offence of public nuisance with a new statutory offence of greater scope. A will commit that offence if A causes serious harm to the public or a section of the public. Serious harm is broadly defined; it includes any damage to property, serious annoyance, or serious inconvenience. A person convicted of statutory public nuisance is subject to a maximum term of imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, a fine, or both.

JUSTICE has expressed two main concerns about this clause; these appear to overlap. It is concerned, first, about “the context in which the offence is being introduced. Public nuisance as a common law offence is a broad offence … [i]t is not specifically targeted at policing protests.”7 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [26]

This is undoubtedly accurate but relatively unimportant; what matters is whether the offence of public nuisance may be legitimately deployed in a public order context. JUSTICE says “Clause 59 would … represent the potential criminalisation of every single protest undertaken. This would undoubtedly incur serious violations of Articles 10 and 11 ECHR.”8 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021 paragraph [28]

The second JUSTICE concern appears to centre on the new 10 year maximum sentence for the offence with the prospect that “introduction of a relatively high maximum sentence would lead to a change in sentencing practices which would result in more protesters receiving a custodial sentence when they are charged with public nuisance.”9 JUSTICE Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill House of Commons Committee Stage Briefing May 2021paragraph [29]

It would plainly not be right to use a recast offence of public nuisance to prosecute a peaceful protest that, for example, occasioned serious annoyance, but the JUSTICE critique appears to ignore the role of (1) the principle of legality, reinforced by section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998, in tempering any overly expansive interpretation or application of the new offence and (2) that both Articles 10 and 11 will considered and applied in the prosecution of any person for public nuisance arising out of peaceful protest.

Next chapterThe Liberty Critique

Liberty criticises the proposed amendment of sections 12 and 14 of the Public Order Act 1986 to criminalise breach of a condition imposed by police in circumstances where a person “ought to have known” the condition existed. Liberty says “[t]his would have the effect of criminalising people who unwittingly breach conditions the police impose and criminalise behaviour that would not in itself be unlawful, but for the imposition of these conditions.”10 Liberty’s Briefing on the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill for Second Reading in the House of Commons March 2021 paragraph [15] Libertys-Briefing-on-the-Police-Crime-Sentencing-and-Courts-Bill-HoC-2nd-reading-March-2021-1.pdf (libertyhumanrights.org.uk) Libertys-Briefing-on-the-Police-Crime-Sentencing-and-Courts-Bill-HoC-2nd-reading-March-2021-1.pdf (libertyhumanrights.org.uk)

This is misleading; the offence requires culpability. An offence is not committed by A who breaches a condition unknowingly unless A ought to have known of the condition. It will be for the prosecution to prove that A ought to have known of it. This is a reasonable allocation of the moral burden. Under the present law the prosecution must prove that A knew of the condition; this may often be difficult to establish to the criminal standard of proof even when it is overwhelmingly clear that A ought to have known of the relevant condition. An objective standard (a requirement of reasonableness) is far from alien to our criminal law, as section 1(1)(c) and 1 (2) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 exemplify.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights critique

The Joint Committee on Human Rights Report on Part 3 (Public Order) of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (HC 331: HL paper 23) was published on June 22 2021. Its timing is, perhaps, unfortunate; the report arrives only three days before the judgment of the Supreme Court in DPP v Ziegler and others [2021] UKSC 23 delivered on June 25 2021, a judgment important for the interplay between protest and the ECHR.

In its report the Joint Committee make an attack on a fundamental aspect of the addition of “noise which will have a relevant and significant impact on persons in the vicinity” as justifying the imposition of conditions by police. It will be recalled that noise may be judged to have a significant impact on a person in the vicinity if it may cause persons of reasonable firmness to suffer serious unease.

The Committee’s critique is at paragraph 39:

“It is not clear to us what right the public has to be free from “serious unease” that might result from peaceful and otherwise lawful protest. Whilst the legitimate aim of protecting the ‘rights and freedoms of others’ is not limited to protecting those rights and freedoms set out in the Convention, this does not mean it is unbounded. We have been unable to identify any other examples of the law prohibiting behaviour that causes ‘serious unease’. There is a risk that relying on ‘serious unease’ to impose conditions on peaceful protests would breach Articles 10 and 11 by failing to meet a legitimate aim.”11 The Joint Committee on Human Rights Report on Part 3 (Public Order) of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (HC 331: HL paper 23) paragraph [39]

This passage also invokes ‘risk’ in terrorem. As noted above, the issue is not the existence of risk but its quantification. In fact, it seems reasonably clear that the state of being free from ‘serious unease’ is protected by Article 8 ECHR. Can it be doubted that state action (or inaction) that resulted in ‘serious unease’ could give rise to a plausible claim under section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998 founded on Article 8 ECHR? What if a majority of residents of a neighbourhood decided to protest a grant of planning permission to a local resident decided to blare horns outside that person’s house at a level that caused serious unease to that person and those living near him? In such a case (as in many instances of protest) the balance is not merely between a group of citizens and the state but how the rights of one group of citizen to protest peacefully is to be harmonised with the rights and freedoms that other citizens enjoy, including their rights under Article 8 ECHR.

When dealing with clause 59 the Committee is right to point out in the current draft “could be read as meaning the offence is committed where serious harm is caused to one person rather than the public or a section of the public.” This has the result that the new offence is much broader (the Committee simply says broader) than the common law offence of public nuisance. Such a transformation is unnecessary and the Committee is right to suggest that the Bill should be amended so that the offence of public nuisance “will only be committed where serious harm is caused to the public or a section of the public.”12 The Joint Committee on Human Rights Report on Part 3 (Public Order) of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (HC 331: HL paper 23) paragraph [111]

DPP v Ziegler and others

The decision of the Supreme Court in DPP v Ziegler and others [2021] UKSC 23 delivered on June 25 2021 is important not only as authority but also as an example of the kind of protest now commonly encountered by police.

The appellants were charged with wilful obstruction of a highway contrary to section 137 of the Highways Act 1980 (“the 1980 Act”). Section 137 of the 1980 Act provides: “137. Penalty for wilful obstruction (1) If a person, without lawful authority or excuse, in any way wilfully obstructs the free passage along a highway he is guilty of an offence and liable to a fine not exceeding level 3 on the standard scale.”

In this case the obstruction consisted of lying down in the middle of one side of the dual carriageway of an approach road leading to the Excel Centre. The appellants attached themselves to two lock boxes with pipes sticking out from either side. Each appellant inserted one arm into a pipe and locked themselves to a bar centred in the middle of one of the boxes.

The district judge at Stratford Magistrates’ Court dismissed the charges. Having regard to the appellants’ right to freedom of expression under article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (“ECHR”) and their right to freedom of peaceful assembly under article 11 ECHR, the district judge found that “on the specific facts of these particular cases the prosecution failed to prove to the requisite standard that the defendants’ limited, targeted and peaceful action, which involved an obstruction of the highway, was unreasonable”

Following prosecution success in the Divisional Court, the appellants appealed to the Supreme Court where their appeal was allowed. While much of judgments are taken up with the standard of review on appeal, the case is important in emphasising the role that Articles 10 and 11 ECHR continue to play in public order cases. Lord Hamblen and Lord Stephen offer the following statement of principle at the conclusion of Paragraph [68] of Ziegler: “there should be a certain degree of tolerance to disruption to ordinary life, including disruption of traffic, caused by the exercise of the right to freedom of expression or freedom of peaceful assembly”. This is followed, in paragraph [69] with the caution that “This is not to say that there cannot be circumstances in which the actions of protesters take them outside the protection of article 11 so that the question as to proportionality does not arise. [emphasis added] Article 11 of the Convention only protects the right to “peaceful assembly”. As the ECtHR stated at para 92 of Kudrevičius: “[the] notion [of peaceful assembly] does not cover a demonstration where the organisers and participants have violent intentions. The guarantees of article 11 therefore apply to all gatherings except those where the organisers and participants have such intentions, incite violence or otherwise reject the foundations of a democratic society.”

The expression ‘peaceful protest’ is often used as a slogan rather than as description. Save in those (rare) cases where the target of protest is itself unlawful, a protest is an attempt to prevent, whether in the present or in future, from doing something lawful. A (a protester) wishes to impose his will on B (the target of the protest) through the protest. For major issues of national policy a protest will often seek either to impose its will on Parliament or to subvert the will of Parliament. Protesters that self-apply the label of peaceful cannot always be assumed to support the foundations of democratic society.

At the end of season 3 of the Norwegian television drama, ‘Occupied’ the central character exhorts viewers directly on climate change shortly after hackers, at his instigation, have caused an electricity blackout in Moscow: “Don’t wait for democracy to save the planet”. For some protesters the objective matters more than the rights and freedoms of others or the constitutional forms by which change is achieved. Peaceful, that is, truly peaceful, Protest is important, but, more important still, is that the scope for such protest is set, and re-set by Parliament.

Our constitution allocates law-making to the Crown in Parliament; this has, among other advantages, a flexibility of response to emerging circumstances and pressures. If the fears expressed about this Bill are, for the most part, unfounded, it is, nevertheless, right to combine a hope that the Bill will improve the effectiveness of policing with a preparedness to learn and react if the hope should prove to be misplaced.