Authors

Content

Introduction

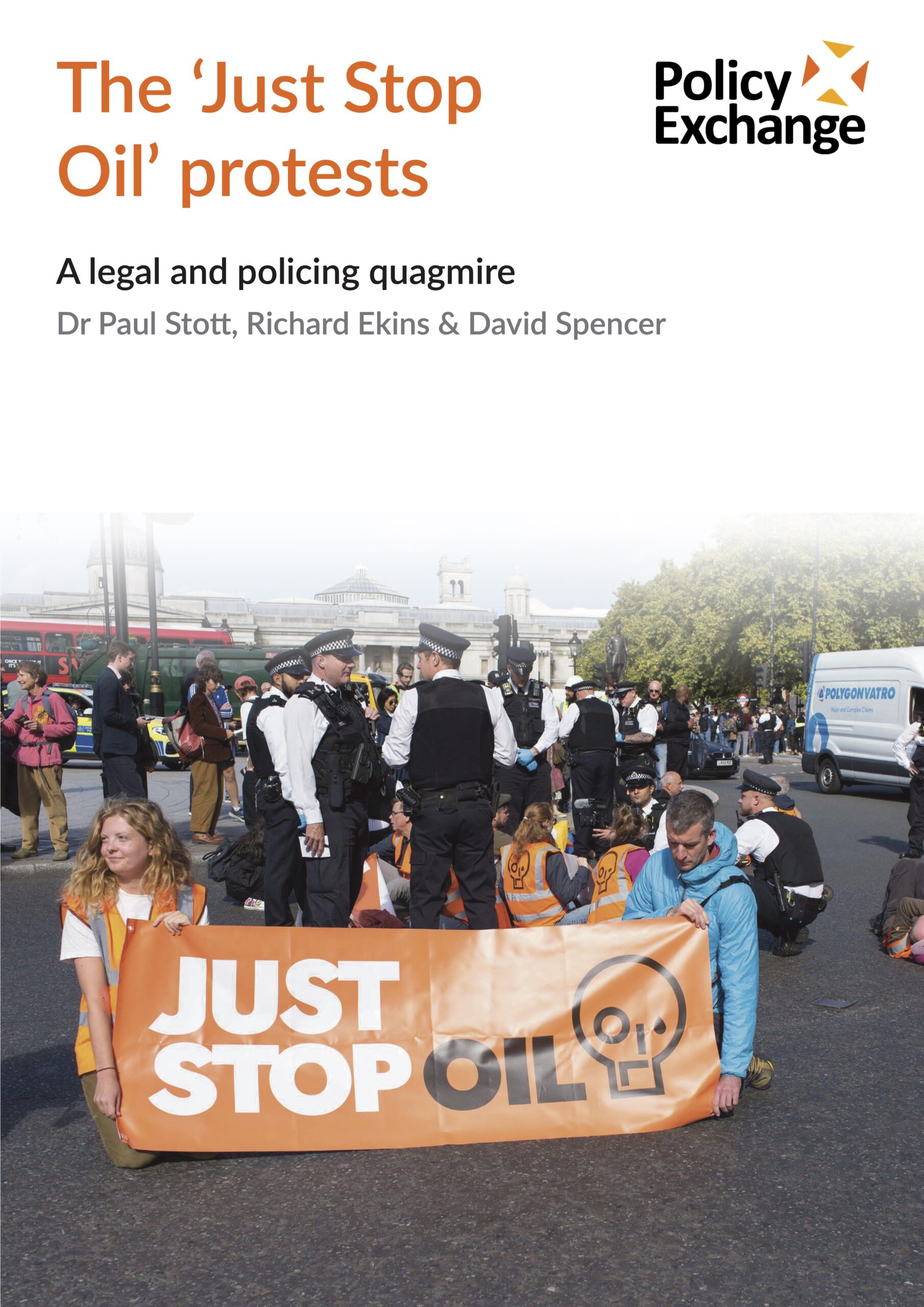

Throughout October, environmental protestors have taken over our streets. Public buildings have been vandalised, works of art daubed with paint, and roads, largely in the capital, brought to a standstill. It has become routine to see orange clad demonstrators sitting down in the road, with members of the public demanding that they move. Police intervention has appeared slow and at times hesitant. The danger of these protests spiralling out of the control of both the demonstrators and the police, as frustrated members of the public take the law into their own hands, is now very real.

How did it come to this?

This Policy Exchange report outlines the inadequacy of the criminal law in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Ziegler, which ruled that deliberate physical obstruction of the highway did not necessarily constitute the offence of obstructing the highway. The Supreme Court ruled that protestors should not be convicted if a conviction would be a disproportionate interference with their Convention rights to protest, which was to be decided at trial. The judgment has spilled over in relation to offences other than obstruction of the highway, including criminal damage. It makes it difficult for the police to know whether an offence has been committed and seems, understandably, to have prompted them at times to be cautious in making arrests, waiting until it is clear that a protest is causing “significant disruption”. Parliament must legislate to change the law, reversing the effect of Ziegler in relation to obstruction of the highway and other offences. However, there is a risk that police forces overinterpret Ziegler and fail to act as swiftly and robustly as the current law permits, partly because they have been hamstrung by the guidance they are given. This is rooted in a five-point approach issued by the College of Policing. When faced with protestors blocking a road, the police are instructed to respond in the following manner:

- Simple appeal – ask the person to comply with your request.

- Reasoned appeal – explain why the request has been made, what law (if any) has been broken, and what has caused the request.

- Personal appeal – remind the person that they may be jeopardising things that are high priorities to them (e.g., loss of free time if arrested, loss of money, loss of income, possibility of a criminal record, loss of respect of their partner and family).

- Final appeal – tell the person what is required and use a phrase that means the same as the following: ‘Is there anything I can reasonably do to make you cooperate with me/us?’

- Action – reasonable force may be the only option left in the case of continued resistance

Even if or when protestors are eventually arrested, the legal system is struggling to deal with offenders who actively seek arrest – often the same people are being arrested time after time. Protestors with multiple repeated arrests or even prior convictions, who are clearly unrepentant about their intention to continue disruptive action of this form, receive minor sentences such as fines, which in the event are sometimes paid by crowdfunding. Existing guidelines on bail conditions and sentencing now appear inadequate.

This brings us to another problem – the protestors themselves. Extinction Rebellion has spawned a series of overlapping groups, committed to breaking the law, and whose leaders possess aims which go far beyond the important and widely accepted aim of mitigating or preventing climate change. This ideological backdrop has been poorly understood. This report highlights the Just Stop Oil “contract”, which commits activists to being arrested (reproduced below), and the cult-like requests made of members not to back out of demonstrations due to the impending horror that is about to befall the world if the protestors’ demands are not immediately met.

Democratic societies thrive on debate and protest. But it is unreasonable for protestors to attempt to secure their objectives by deliberately and repeatedly causing disruption to groups like commuters or people driving their children to school. The law risks being seen as an ass if those who live, work and campaign within the rules can see a particular group of people pursuing their political objectives, however laudable, by unlawful means – and in large measure getting away with it. Exasperated members of the public are beginning to take the law into their own hands, physically picking up and moving protestors who are blocking the roads. The criminal justice system is not coping.

It is time for authorities to step up. Policy Exchange proposes new legislation which Parliament should enact that would make clear that there can be no lawful excuse for blocking the highway if an aim of the obstruction is to interfere with the legal rights of others. Legislation should make similar provision in relation to the offence of criminal damage. The College of Policing guidance to officers must be reviewed, and individual police forces should act immediately when they reasonably suspect that an offence has been committed, even if it is of course true that it will often be difficult to predict whether the court will in the end convict the protestors. This needs to be followed by fresh training for all officers involved in public order policing, to ensure the highest degree of consistency and professionalism.

The Sentencing Council should be invited to issue guidance on punishments where the law has been broken during political protests. Repeat offenders must be punished more harshly than first-time offenders, especially when or if additional offences take place while a person is on bail, or when it is clear that an offender is unrepentant and intends to continue to commit similar offences. The protestors discussed in this paper are not engaging in civil disobedience insofar as they are not pleading guilty and accepting the legitimacy of the penalties imposed by law. Public authorities should also make full use of their existing rights under the law, seeking injunctions to restrain trespass and damage and vigorously seeking compensation for the loss that Just Stop Oil deliberately inflicts.

Next chapterWho the groups protesting are and why these demonstrations are different

Paul Stott

Just Stop Oil protests caused repeated disruption in London during October. They also brought chaos to traffic across the southeast by scaling the Queen Elizabeth II bridge, thus blocking the Dartford Crossing for two days. Who are Just Stop Oil? And why do the authorities appear to struggle to control actions by environmental protestors in a way that does not seem to occur with other political campaigners?

Just Stop Oil is one of series of overlapping groups and activists who dominate the environmental protest movement. Extinction Rebellion (or XR, as it is frequently termed by its activists), Insulate Britain, Animal Rebellion and a score of other organisations make up other parts of the same eco-system. They are not replacements for, or rivals to each other, but part of the same political process, and each has grown out of Extinction Rebellion. Linkages in terms of leadership, foot soldiers, messaging and most importantly strategic aims, make any difference in logo or banner largely irrelevant.

In considering the groups covered in this report, it is necessary to draw a distinction between the methods they have been utilising, and their cause. This paper does not seek to reject attempts to mitigate climate change and takes no position on wider environmental debates. It takes issue with the conduct of many of the protests and the wider political goals at play.

What the protestors believe

Extinction Rebellion began with three core demands – to tell the truth about what they see as a climate emergency, to act now to remedy the situation, and to create citizens assemblies, ‘well informed by the best experts’, to decide how the changes needed in society will be implemented.1Rupert Read and Samuel Alexander, Extinction Rebellion: Insights from the inside (Simplicity Institute, 2020), pp. 1–2. Those demands remain, although some local groups, have started to add a fourth set, which relate to colonialism and gender.2See for example Tower Hamlets Extinction Rebellion https://xrtowerhamlets.org/ and Leeds Extinction Rebellion Our demands – XR Leeds

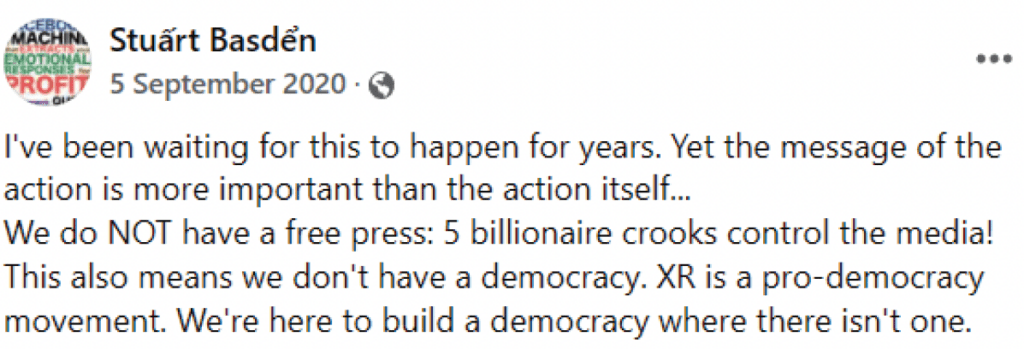

The categorisation of Extinction Rebellion as exclusively committed to fighting climate change, promoted by many acting in the group’s name,3https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/26/facts-about-our-ecological-crisis-are-incontrovertible-we-must-take-action and widespread in initial media reports,4https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/26/we-have-a-duty-to-act-hundreds-ready-to-go-to-jail-over-climate-crisis is in practice rejected by core figures. For example, co-founder Stuart Basden indicated a much broader set of political objectives in 2020 when supporters besieged newspaper printing plants. He describes Extinction Rebellion as a “pro-democracy movement” existing to “build democracy” in a society lacking such freedoms:5https://www.facebook.com/thugsb/posts/10217649193117868

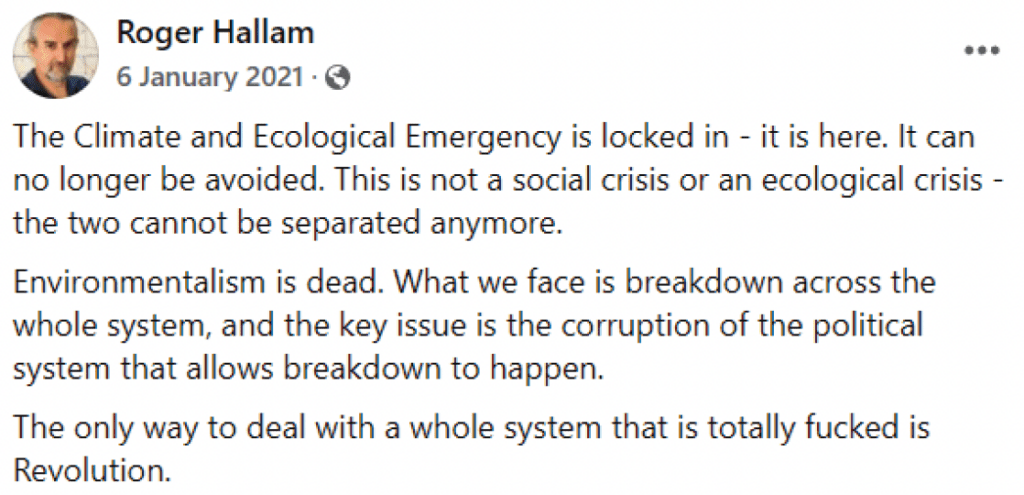

A co-founder of Extinction Rebellion, the ubiquitous Roger Hallam, suggests that the only way to deal with the problems facing this society is ‘revolution’:6https://www.facebook.com/roger.hallam.7/posts/3805690536218568

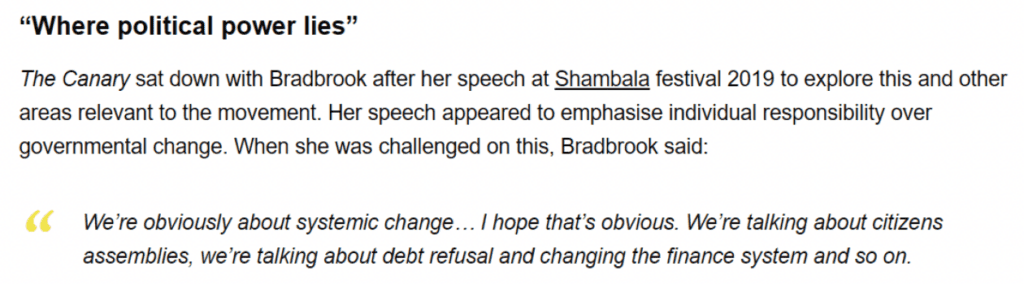

Similarly, another Extinction Rebellion co-founder, Gail Bradbrook describes the movement as being about systemic change, including debt refusal and changing the financial system:7https://www.thecanary.co/exclusive/2019/09/07/extinction-rebellion-co-founder-tackles-the-allegation-she-isnt-challenging-capitalism/

These are the familiar political positions of the revolutionary left. Such rhetoric illustrates a divide between the Extinction Rebellion seeking public support on countering climate change, and the Extinction Rebellion its founders seek. To Extinction Rebellion’s leaders, these protests are about much more than environmental issues. Indeed, as Roger Hallam has stated ‘environmentalism is dead’, the only way forward is revolution.8https://www.facebook.com/roger.hallam.7/posts/3805690536218568

The campaigns

Blue Sandford, in a 2020 guidebook for Extinction Rebellion Youth referred to some of the tactics being utilised:9Blue Sandford, 2020. Challenge everything: An Extinction Rebellion youth guide to saving the planet. London: Pavilion, p. 91 ‘Swarming (short repeated roadblocks – very low risk of arrest, but the public often get aggy) sit-ins and die-ins (symbolically dying to make a point) are also widely used.’ The public is indeed getting frustrated, and at times aggressive (or ‘aggy’ as protestors put it) in its response.10This example was one of several during October: https://www.itv.com/news/2022-10-15/public-clash-with-just-stop-oil-protesters-blocking-east-london-road But as soon as attention is focused on responding to one group, such as Insulate Britain for its M25 protests, a new campaign has tended to appear. Why?

As with other aspects of the Extinction Rebellion eco-system, separating Insulate Britain and Extinction Rebellion in any meaningful way is a difficult business. Many of the protests appear identical, and utilise very similar tactics – blocking roads, locking on to platforms, vandalism such as smashing windows or spraying targets with paint, and occupations. The campaigns have many of the same leaders. Roger Hallam writes11https://www.facebook.com/roger.hallam.7/posts/4804916489629296:

I designed the initial plan and led the mobilisation process for the most successful act of mass civil disobedience in modern UK history: the XR rebellion of April 2019 when 1200 people were arrested in 10 days in central London.

I designed the plan for the fastest recognised campaign in modern UK history: Insulate Britain which went from zero to 77% name recognition in four weeks. This was achieved with around 100 people and hardly any money.

In January 2022, Roger Hallam began to travel around existing environmental groups and university campuses in a new recruitment drive. This sought to place the previous Insulate Britain and Extinction Rebellion campaigns on the back burner, and to put a new organisation, Just Stop Oil centre stage:

Never short of hyperbole, alongside warnings on flyers (above) indicating starvation, slaughter and the destruction of people’s towns, Hallam likened willing participants to activists who hid Jews during the Holocaust, stating: 12https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/insulate-britain-founder-recruits-student-revolutionaries-to-save-planet-t5sgvbtdp

All the people who did Insulate Britain had one thing in common. They can’t live with themselves if they didn’t act . . . Why did people take in the Jews? According to Tim Snyder, a top researcher on it, the only thing people had in common was ‘self-knowledge’. What does that mean? It means they could not stand there. They could not be bystanders.

The pre-existing network promotes the new campaign, delivering the message of a new campaign to Extinction Rebellion’s foot soldiers. This includes regional XR branches –although they may opt to add the caveat that ‘This is not an XR event’:13https://twitter.com/XRDerby/status/1484981850615562245

The speed with which contemporary environmental campaigns build is remarkable. Just Stop Oil’s website was registered on 21 January 2022.14Whois juststopoil.org accessed 31 January 2022. On 14 February two campaigners, Louis McKechnie and Hannah Hunt, delivered an ultimatum to Prime Minister Boris Johnson. This quoted back at the Prime Minister his words from past statements on the environment, including at COP26, that young people were having their future stolen from them, and that they have a right to be angry. It went on to state:

Just Stop Oil is demanding that: The UK government makes a statement that it will immediately halt all future licensing and consents for the exploration, development and production of fossil fuels in the UK. If you do not provide such assurance by March 14th 2022 it will be our duty to intervene – to prevent the ultimate crime against our country, humanity and life on earth.15Just Stop Oil, Press Release, 14 February 2022, https://juststopoil.org/2022/02/14/breaking-just-stop-oil-youth-campaigners-deliver-ultimatum-to-boris-johnson/

The Just Stop Oil press release which accompanied this ultimatum saw McKechnie and Hunt described as ‘two young supporters’ of the group, and their respective ages – 21 and 23 – published. For good measure, the statement added:

We either come together as humanity or we die. Youth know which they choose. They have already chosen. They are in the streets to demand a future. We are all in the streets to make sure they get it. It’s as basic as that.

After the somewhat Dad’s Army appearance of Insulate Britain’s protestors,16Nine Insulate Britain protestors who appeared at the High Court in December 2021 had a combined age of 428. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-59672254 and to an extent Extinction Rebellion itself, Just Stop Oil was portraying itself in a distinct manner – as young people let down by their elders, fighting to save the future. The political framing was skilful. But the reason Just Stop Oil can develop a national network so quickly, is because it is turbo charged by the activist networks from which it emerges – most notably Extinction Rebellion.

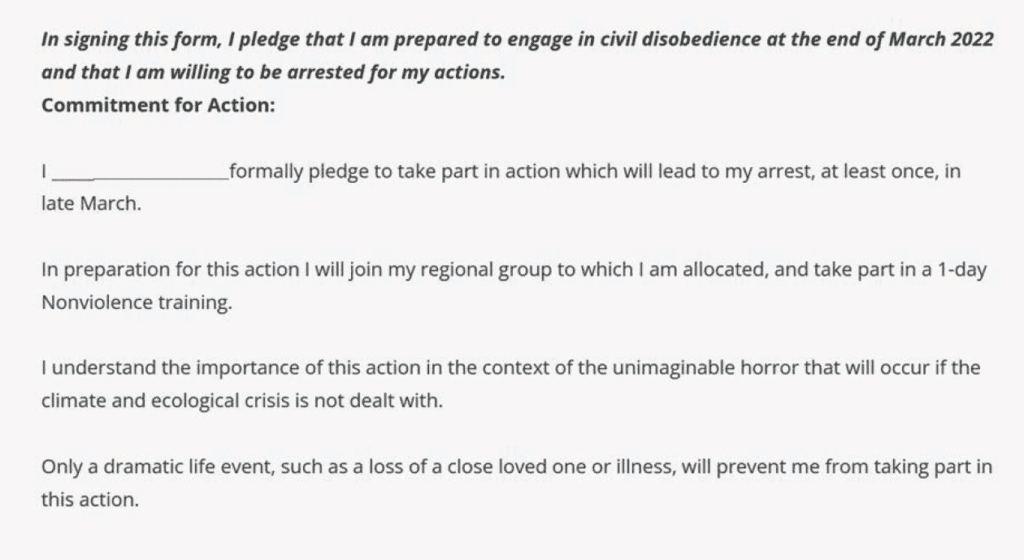

For those drawn into the campaign, there was a message with a harder wedge. Just Stop Oil’s importance was stressed with rather cult-like messaging on a contract activists were asked to sign17https://web.archive.org/web/20220109014519/https:/actionnetwork.org/forms/civil-resistance-2022/:

I understand the importance of this action in the context of the unimaginable horror that will occur if the climate and ecological crisis is not dealt with.

Only a dramatic life event, such as a loss of a close loved one or illness, will prevent me from taking part in this action.

Shortly afterwards, the form presented added a commitment to action that would lead to ‘at least’ one arrest:

This form has since been deleted, possibly as pledging to take action leading to an arrest could leave an individual open to further criminal charges.18We only have the above screenshot, not a link, for this form. However, it has been referred to in subsequent injunction proceedings. See for example 10.1.3 of proceedings by ExonMobil 4 April 2022: Claimants’ skeleton argument (exxonmobil.co.uk) It also illustrates a key difference between this movement and other political campaigns. Those demonstrating for workers’ pay rises or campaigning for renationalisation, to take just two examples, do not box their supporters in with written contracts demanding a guarantee of attendance unless a relative has died. Nor do they ask people to commit to being arrested. Sign-up forms for the October month long Just Stop Oil actions include a box to be ticked if you are willing to ‘Take action which will risk arrest this October’19https://actionnetwork.org/forms/we-all-want-to-just-stop-oil/.

Where next?

Predicting the imminent end of the world is an approach once associated with religious cults. Extinction Rebellion’s Rupert Read recognises the risks for the movement of making predictions that do not come true. However, he does not retreat: ‘What I think we can know is this civilisation is finished.’20Read and Alexander, 2020, p.25 The end of the world is nigh. A 2019 intervention by Read and Sam Alexander is entitled ‘This civilisation is finished: conversations on the end of empire and what lies beyond.’21Rupert Read and Samuel Alexander, This Civilisation is Finished: Conversations on the end of Empire – and what lies beyond (Simplicity Institute, 2019). The prophecies of doom are particularly directed towards young people, with Read and Alexander saying: ‘I fear that some of you are unlikely to grow old.’22Read and Alexander, 2020, p. 44

All of this has an effect. These campaigns host activists who claim to be depressed or even suicidal via the knowledge their political awareness has brought them – what is referred to as ‘climate grief’. How this will impact future campaigns, and the mental health among campaigners is unclear. There has even been an instance of self-harm by a climate campaigner in the UK – in September Kai Bartlett of the campaign End UK Private Jets set his arm on fire after running onto court during a tennis tournament in London.23https://twitter.com/EndUKPrivateJet/status/1573339153978347521 Bartlett had previously attended Extinction Rebellion protests at an Amazon Distribution Centre in Greater Manchester,24https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/if-dont-see-change-might-22289010 and chained himself to a goalpost, in support of Just Stop Oil, during an Arsenal v Liverpool football match in March.25https://www.mirror.co.uk/sport/football/news/everton-newcastle-stop-oil-goalpost-26496932

Things may get even more serious. On 23 April 2022, a US climate change activist, Wynn Alan Bruce, died after setting himself on fire outside the Supreme Court in Washington DC26Climate activist Wynn Alan Bruce dies after setting himself on fire outside US Supreme Court on Earth Day | US News | Sky News the previous day – Earth Day.27Earth Day is an annual event, held since 1970, to “diversify, educate and activate the environmental movement worldwide”. See Earth Day: The Official Site | EARTHDAY.ORG Howard Breen, an Extinction Rebellion activist from Vancouver, has sought to end his life by participating in Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) programme. In 2017, Breen was diagnosed with what is referred to as ‘eco-anxiety’ and describes himself as depressed. He has so far been refused permission to join the MAID scheme and in this way to end his life.28Ryan Hook, https://www.vice.com/en/article/k7wd4e/canada-assisted-suicide-climate-anxiety, 12 May 2022.

This brings a disturbing element to our politics. The messaging of Extinction Rebellion may attract those likely to commit acts of self-harm and its rhetoric worsen their position rather than improve it. The negative impact upon young people’s mental health, of campaigns which tell them they may not live to be old, requires much further evaluation. They also raise a second, worrying question. There must be a risk that these levels of despair, which animate the antics of Extinction Rebellion and its offshoots and result in some self-harm, may in time spill over into violence towards others.

Case study: Gabriella Ditton of Extinction Rebellion, Burning Pink, STOP HS2, Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil

This section of the report covers an individual prominent in the environmental protests in recent years and serves as an indicative example of many of the issues raised for the public, and the criminal justice system, by these demonstrations, most notably that activists appear able to break the law repeatedly, imposing disruption on the public and attacking property.

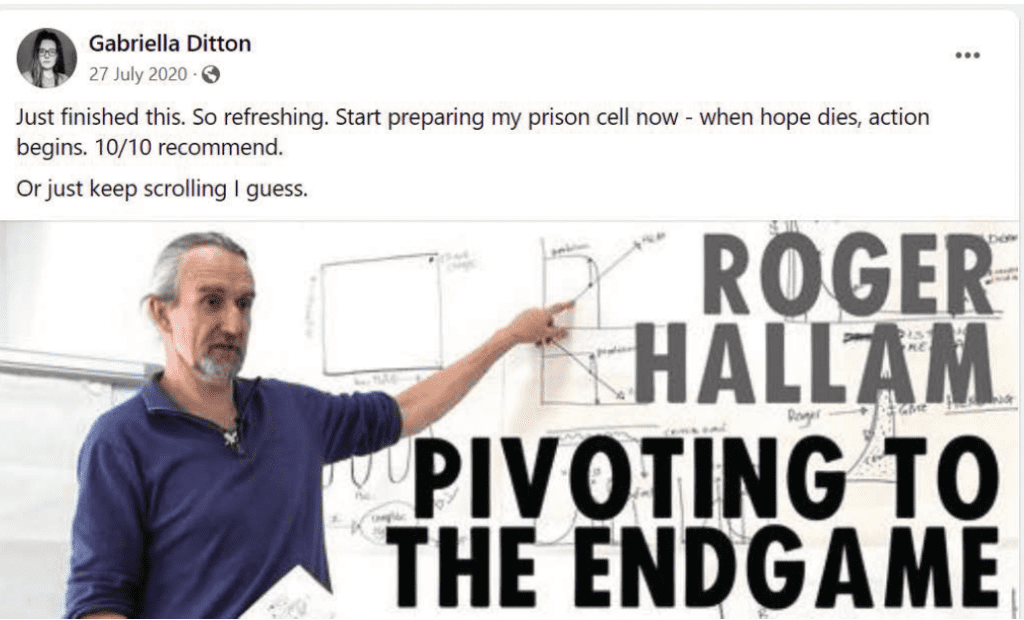

Gabriella Ditton comes from Norwich and worked as a designer and animator.29https://dittonpendle.wordpress.com/the-directors/ as an example of her work see 2016 animation on social media addiction https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-De8I74z4Q Her education included seven years at Wymondham College, a coeducational day and boarding secondary school in Norfolk.30https://www.wymondhamcollege.org/971/boarding-fees Ditton took a BA at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham,31https://dittonpendle.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/gabriella-ditton-cv.pdf and her education also included a stint in the United States at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.32https://www.facebook.com/gabriella.ditton Ditton publicly associated herself with Extinction Rebellion in 2019,33https://www.facebook.com/gabriella.ditton/posts/10157099348710761:0 helping her local group XR Norwich with their campaigns.34https://twitter.com/AmesIsTheName/status/1155738020756090880 and https://twitter.com/greenmattwhite/status/1150415395263827969

By 2020, it appears Extinction Rebellion, and in particular its co-founder Roger Hallam, had so convinced Ms Ditton that a social media statement indicated she was ready to go to jail for the cause:35https://www.facebook.com/gabriella.ditton/posts/pfbid02FnfKVZrt4wzoX9neSAHTpzT5EME3mmt5YQ9LUcpHYE3nunMeL1Nqnb2q6kDUWcypl

Gabriella Ditton had previously described herself as driven by her ambitions, wanting to become ‘an iconic designer and/or director’ but by 2020 she chose to leave behind her ‘career goals and materialistic desires’ – describing activism and civil disobedience as ‘fun’, adding ‘Being arrested isn’t scary, but societal collapse is’.36https://dittonpendle.wordpress.com/the-directors/ and https://www.facebook.com/gabriella.ditton/posts/pfbid02SFks2KKEA44hGGnX5D33N4w6yEPQLod2Az3SdvcsAQLngzjviMqAEruKZKoiCf97l

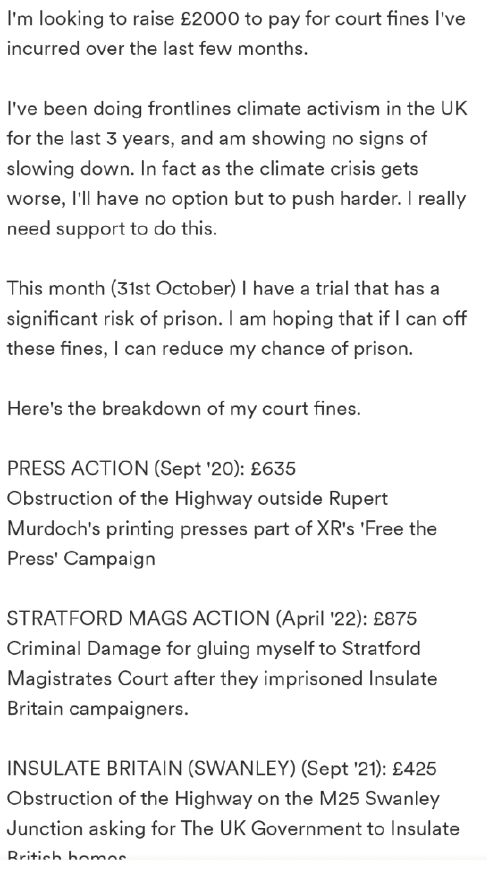

From this point, Ditton was often leading from the front – when she received criminal convictions for breaking the law at protests, she used crowdfunding to raise money to pay off fines.37https://www.facebook.com/gabriella.ditton/posts/pfbid02oPrmmfixxubY7cG7tu31ExkpjryHcfEHS2UxRyMNjF6jzfUh9EawcyP2DEDHRUMbl This included actions, arrests, and trials in Cambridge – where she admitted two counts of criminal damage.38https://www.cambridge-news.co.uk/news/cambridge-news/live-extinction-rebellion-court-cambridge-18789959

- February 17 2020: Digging up of Trinity College’s lawn

- February 18 2020: Attack on the Schlumberger Building

Confusingly, when Extinction Rebellion placed a publicity page for her on their website, they gave Ditton the role of a ‘carer’ in a banner headline, only stating underneath her profession of ‘animator’.39https://extinctionrebellion.uk/2021/01/08/gabriella-ditton-26-carer-from-norwich/ That page also lists additional arrests in the environmental cause:

- October 2019: Obstruction of a highway

- July 2020: Schlumberger Oil and Gas HQ in Cambridge

- September 2020: Newspaper printworks blockade at Broxbourne

- November 2020: Norwich crane protest

In February 2021, Ditton was also arrested as a ‘Burning Pink’ activist after an action in Norwich.40https://www.edp24.co.uk/news/crime/norwich-pink-paint-protest-accused-in-court-8152264 The Burning Pink Party, also known as Beyond Politics, was launched in 2020 by Extinction Rebellion activists.41https://www.cambridgeindependent.co.uk/news/new-anti-political-party-burning-pink-threatens-civil-disobedience-in-cambridge-9148727/?cmpredirect&lang=en Ms Ditton was also arrested as a ‘STOP HS2’ protestor after an action in Watford in October 2020.42https://www.watfordlondon.uk/news/twenty-one-protestor-charged-in-connection-with-hs2-protest-in-denham/

Later in 2021, she was instrumental in the Insulate Britain protests, running events for the campaign.43https://www.facebook.com/events/295793089201119/ She was even filmed singing Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, whilst blocking a road in London, before being arrested by police.44https://www.newsflare.com/video/465158/insulate-britain-activist-gabby-dutton-sings-bohemian-rhapsody-before-being-arrested-whilst-blocking-road-in-london Ditton became a spokesperson for the group – appearing on media outlets such as GB News.45https://twitter.com/GBNEWS/status/1448388784169668610?s=20&t=PggeHobQee0iMT_cctf39g

By November 2021 she claimed she had been arrested 16 times.46https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/gabriella-ditton-discusses-climate-change-activism-8507174 Here she is pictured (below, last on the right) in Sussex on May 10, 2022, following a hearing at the Lewes Crown Court. With the criminal justice system creaking from the impact of funding issues, the Covid lockdown and barristers strikes, the trial over this particular arrest has been scheduled for October 2023.47https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/20128436.brighton-activist-pleads-not-guilty-public-nuisance-charge/

2022 saw Ms Ditton add the colours of Just Stop Oil to the myriad of masks she wears. Once again she was pivotal to the campaign and ran events to inform and recruit others.48https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/our-responsibilities-at-this-time-with-gabby-ditton-newbury-tickets-401395373367 Whilst critical of transport patterns in this country, a distinguishing feature of the environmental movement is that its activists are hyper-mobile. As well as appearing at protests across east Anglia, London and the south-east, in May 2022 Gabriella Ditton was part of the Just Stop Oil group that blocked Nustar Oil Terminal in Glasgow.49https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/norwich-activist-blocks-scotland-oil-terminal-8947152

What happens at court?

It is hard to imagine someone from an under privileged background, or a campaigner arrested sixteen times advocating for an unfashionable cause, receiving a generous platform in their local newspaper to state their case. In the Norwich Evening News Ms Ditton explained her experiences to readers, ‘We’re given lots of warnings, police don’t want to arrest you, especially when you’re peaceful, it’s loads of paperwork, and they have to go to court and everything. 50https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/gabriella-ditton-discusses-climate-change-activism-8507174

What happens if someone is arrested and ends up in court? Gabriella Ditton was part of an Insulate Britain group that disrupted an estimated 18,000 drivers on the M25, including an ambulance carrying a patient, by sitting across Junction 3 on September 29 2021.51https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/crime/norwichs-gabriella-ditton-not-guilty-m25-protest-8895648 Just over a year later, her case was finally heard at Horsham Magistrates Court on 11 October 2022. 52Horsham Magistrates Court. Case reference 2200072946/46XY946121

At the trial, the precedent set by the 2021 Supreme Court case of DPP v Ziegler (discussed later in this report) took centre stage.53https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2019-0106.html The prosecutors opening remarks were designed to highlight why Ziegler did not apply to the case. The police witnesses gave testimony emphasising the consideration they had given, before making the arrest, to the ‘balancing act’ of rights required by the Ziegler case. When issuing her judgement, the Judge’s reasoning took into consideration each of the ‘range of factors’ in Ziegler in a clear attempt to show she had stringently applied her judgement against the backdrop of the Supreme Court ruling.

When Ditton gave evidence, and as she was representing herself, part of her statement was delivered in a question-and-answer session with the sitting judge, she was asked why she felt it legally justified to block M25/M20 traffic instead of directing her protest at those responsible for policy – the government. Ditton’s response was telling – she said ‘we’ had tried blocking roads around Parliament Square two years ago, but it was pointless, and nobody took any notice. This was why they (Insulate Britain) had decided to act on the M25.

Ditton’s use of the word ‘we’ passed everyone by, including the judge and prosecutor. Yet as a statement it illustrates a significant point. In the eyes of the protestors themselves, Insulate Britain, which did not exist in 2019 or 2020, and Extinction Rebellion, whose colours Ditton was wearing when protestors blocked roads around parliament in 2019 and 2020 are just one movement. The various names and campaign logos are simply flags of convenience in order to create the impression of a much larger, more diverse movement than actually exists.

What happens after court?

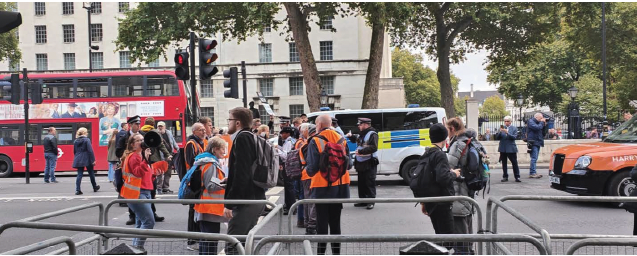

On the 13 October 2022 – just two days after the judge in Horsham found Gabriella Ditton guilty and fined her £430 – there was a protest under the banner of Just Stop Oil, which temporarily blocked traffic around Parliament Square. This was part of a series of protests designed to ‘Occupy Westminster’ throughout the month of October.54https://actionnetwork.org/forms/we-all-want-to-just-stop-oil/ The image below shows the protest as it stopped outside of Downing Street. The protestor on the left, leading the march and holding the megaphone, is Gabriella Ditton.

Photo: Copyright: Policy Exchange, 13 October 2022

What makes this particular protest especially galling can be found in recalling Ditton’s own words. If, as she had said just two days earlier in the witness box at Horsham Magistrates Court, blocking roads around Parliament had proved to be a pointless exercise, what justification can she still have for stopping traffic there later in the same week? A few hours after being present at the protest in Whitehall, Gabriella Ditton was part of the group that attacked and defaced New Scotland Yard.55https://news.sky.com/story/amp/just-stop-oil-protesters-spray-paint-new-scotland-yard-12720387 She told the Press Association:

We did try petitions and marches and strongly worded emails before this, but that didn’t work. And now we’re in a situation where all of life on earth could be destroyed forever in the name of short-term profit. So yeah, I absolutely support this. It’s peaceful, it’s non-violent, it’s stressful to watch but what other choice do we have?”

On 20 October 2022 a GoFundMe page was launched by Gabriella Ditton entitled ‘Help Gabby pay court fines’.56https://www.gofundme.com/f/gabby-pay-court-fines This aimed to raise £2000 to cover fines before a scheduled court appearance, where Ms Ditton feared being sent to prison.

The case study of Gabriella Ditton details several core elements of this movement, and the difficulty society is having in both reading and responding to events. The impression may sometimes be given that the environmental protest movement comprises a series of dynamic, fast-growing campaigns. However, this may be illusory, with the same committed activists being arrested and re-arrested over and over, wearing different campaign t-shirts. There is little or no fear of arrest, and any fines which are levied are a temporary inconvenience, potentially covered by crowdsourcing. At court, legal discussion is often dominated by intricacies of human rights law, of which public understanding is generally low. The next section of this report seek to address that gap.

Next chapterThe state of the law of public protest

Richard Ekins

The recent rise of public disorder is driven in part by the inadequacy of the criminal law, which should (and, until recently, did) clearly prohibit acts of “protest” that involve (a) deliberate obstruction of highways, in order to delay (or halt) traffic and to inconvenience the public, or (b) damage to property, whether public or private, in order to draw attention to the protestor’s cause or in order to carry out the protestor’s political objective. The criminal law, as recently developed by our judges, fails adequately to prohibit the acts in question, making it difficult for police to protect the interests of the law-abiding general public by, for example, promptly arresting protestors. When protestors are arrested and charged with criminal offences, the trials are likely to become political, frustrating their proper function of convicting, and appropriately punishing, the guilty. Parliament must urgently act to clarify and strengthen the law.

Section 137 of the Highways Act 1980 says that it is an offence ‘if a person, without lawful authority or excuse, in any way wilfully obstructs the free passage along a highway.’ Protestors are now routinely obstructing free passage along the highway. Many are in the end arrested, but they are not always arrested immediately. Instead, police seem to understand themselves only to be free to arrest and charge protestors who are obstructing the highway once sufficient time has passed for the obstruction to constitute “serious disruption” to road users and the public. This understanding of the law, which can be seen whenever police patiently talk to those occupying the roads, encouraging them to leave rather than arresting them for obstruction, appears to be grounded in the Supreme Court’s judgment in DPP v Ziegler.57[2021] UKSC 23

In that case, a number of protestors were arrested and charged under section 137, but acquitted at trial by the magistrates. The High Court quashed their acquittals and directed convictions. However, on appeal the Supreme Court restored the acquittals, ruling that deliberate physical obstruction of the highway by protestors, which prevents others from passing along the highway, is lawful if criminal conviction would be a disproportionate limitation on the protestors’ Convention rights to free expression and free assembly (often bundled together, not entirely accurately, with freedom of belief under Article 9 as “the right to protest”). In blocking the highway, and deliberately stopping others from using it, it was held that the prosecution had failed to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the protestors were not lawfully exercising their rights under Articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Thus, “lawful excuse” in section 137 had to be read such that the obstruction of the highway would be lawful – not a breach of the criminal prohibition – unless the prosecution could prove that conviction would be a proportionate (and thus justified) interference in the exercise of the rights in question. The judgment confirms how far the law has changed since 1999, when, in DPP v Jones,58[1999] 2 AC 240 Lord Irvine could say that ‘any “reasonable or usual” mode of using the highway is lawful, provided it is not inconsistent with the general public’s primary right to use the highway for purpose of passage and repassage.’ Now, “the general public’s primary right to use the highway” is routinely violated.

Enactment of the Human Rights Act 1998, which came into force in October 2000, made it inevitable that “lawful excuse” would be read to include exercise of one’s Convention rights to speak and to assemble. However, the Ziegler judgment runs together the meaning of “lawful excuse”, which has to be read compatibly with Convention rights if possible, with the question of whether conviction would be a disproportionate interference in the exercise of Convention rights. The judgment effectively assumes that convicting an offender is an act of a public body (a court) which cannot lawfully act in a way that is incompatible with Convention rights, per the terms of section 6(1) of the Human Rights Act. But while arrest and prosecution are discretionary, conviction is not. If the elements of the offence are made out, the court must convict,59This is not a prediction about what a court will do in any particular case; it is a statement of legal duty. in which case section 6(2) of the 1998 Act applies, which provides that subsection (1) does not apply if primary legislation means that the public body could not have acted differently. The Supreme Court should have asked whether the 1999 understanding of section 137 was compatible with the Convention, and if it was, should have affirmed the priority of the “general public’s primary right to use the highway”.

The significance of the Ziegler judgment is that the Supreme Court ruled that deliberate physical obstruction of the highway – that is, conduct which is intended to prevent others from using the highway – is capable of being protected by “lawful excuse” and is thus not criminal unless the prosecution can prove, to the criminal ‘standard’, that conviction is “necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety and the protection of the rights and freedoms of others”. The majority asserted that Convention rights require ‘a certain degree of tolerance to disruption to ordinary life, including disruption of traffic, caused by the exercise of the right to freedom of expression or freedom of peaceful assembly.’60Ziegler at [68], per Lord Hamblen and Lord Stephens While this assertion certainly betrays indifference to the rights and freedoms of other road users, for whose protection section 137 was enacted, the Court did not rule that obstruction of the highway was always lawful. Violent protest would not come within the scope of “lawful excuse” and a criminal conviction for obstruction that caused significant disruption would not necessarily be disproportionate. Everything turned on the facts of each individual case and on whether in relation to those facts a conviction was proved to be “necessary in a democratic society” (the “fact finder” in a given trial would have to make this assessment).

The Ziegler case itself concerned a protest in September 2017 against the Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) arms fair, held at the Excel Centre in East London. Protestors lay down on one side of an approach road leading to the Excel Centre and locked themselves to hollow boxes. The police arrested them within five minutes, but it took 90 minutes to disassemble the boxes and remove the obstruction. The members of the Supreme Court panel disagreed about how to classify the protest and whether to think about it as a limited obstruction of one way into the Centre or to think about it as a complete obstruction of the relevant part of the highway. For some of the judges, the limited duration of the protest was a point weighing against a conviction being a proportionate response, whereas for others the key point was that the protestors had intended to block the road for much longer and had taken steps to frustrate their removal. (It was very strange to find police efficiency effectively being held against them.) The majority allowed the appeal, restoring the decision at first instance that a conviction in this context would be disproportionate. It would seem to follow, even if the Court did not spell this out, that it was probably unlawful (because a disproportionate interference in Convention rights) for the police to arrest the protestors in this case after only five minutes. For the police to have been on safe ground, they would have needed to have waited until the protestors were reasonably thought to be committing an offence, which would only occur when no “lawful excuse” was open to them. That is, for an arrest to be lawful, the police would have to reasonably suspect that the obstruction to the highway was causing significant disruption, in view of its duration and extent. However, it is important to note that the Supreme Court ruling directly concerns the lawfulness of conviction not arrest.

While, the Court of Appeal has largely resisted the application of Zeigler to offences which do not include a “reasonable” or “lawful excuse” defence,61See DPP v Cucuriean [2022] EWHC 736 (Admin) (aggravated trespass) and R v Brown [2022] EWCA Crim 6 (common law public nuisance) the Ziegler judgment prominently spilled over into trials concerning criminal damage, where again a defence is open to a protestor if he or she has “lawful excuse” for damaging property. In the Colston trial in Bristol earlier this year, a jury acquitted four defendants on charges of criminal damage. The trial judge had left to the jury the defence, clearly grounded in Ziegler, that a conviction had to be a proportionate interference in Convention rights to assemble and speak, which required the jury to decide whether a conviction for this conduct was “necessary in a democratic society”. Leaving this defence to the jury served to compromise the conduct of the trial, opening the door for defence counsel to introduce political questions – and to make political points – that should not have been for the jury to consider or decide.62For analysis of other defences that should not have been left to the jury, see Charles Wide QC, Did the Colston trial go wrong? Protest and the criminal law (Policy Exchange, 13 April 2022)

The Attorney General referred to the Court of Appeal the question of whether exercise of Convention rights can be a defence to a charge of criminal damage. The Court recently ruled that there is no such defence, at least when the damage is more than minor or trivial.63[2022] EWCA Crim 1259 The Court of Appeal distinguished between public and private property, noting that damage to the latter was unlikely ever to be justified as an exercise of Convention rights, thus suggesting that (minor) damage to public property might still be defended on this basis. The damage caused to the Colston statue was clearly more than minor. What is unclear is whether spray-painting (public) property, smearing it with urine and faeces, or hurling soup over the glass frame of an artwork will be unlawful. On any ordinary application of the law of criminal damage, these would be offences. But the Court of Appeal’s judgment, while a welcome correction to the Colston trial and the expansion of Ziegler, leaves open political argument about the merits of conviction in these cases, where the criminal damage in question is relatively minor. Likewise, it is not clear whether protestors who smash bottles of milk in supermarkets or department stores will be able to defend their actions as an exercise of Convention rights. The Court of Appeal’s judgment on the Reference suggests that this defence may not be open, but the point is likely to be argued.

The Supreme Court in Ziegler notes various factors that are relevant in evaluating the proportionality of a conviction for conduct that obstructs the highway. The factors include the location of the protest, its duration, the extent of interference in the rights of others, and the risk of public disorder, all of which the judge or jury must weigh up in order to strike a “fair balance” between the rights of the protestors and the community and thus to decide whether a conviction in this case would be a rational, legitimate interference in the protestor’s Convention rights. The Court implies that the importance of the protestors’ cause and their sincerity in protesting are relevant to evaluation of the proportionality of conviction. The risk in this line of reasoning is of course that it is likely to result in certain protestors enjoying much greater freedom from the criminal law than other protestors. In this regard, it bears noting that Ziegler is being considered again by the Supreme Court in relation to “buffer zones” outside abortion clinics, which impose draconian limitation of Convention rights to speak, assemble or even to pray, limitations which are very distant indeed from the way in which environmental protest is treated – with one judge reportedly telling “courageous” activists that “you have to succeed”. It is obviously wrong for the application of the criminal law to protestors who obstruct the highways or commit criminal damage to vary according to the popularity of their cause.

The law as it has developed appears to have led some police officers to be concerned as to whether it is lawful for them to arrest protestors who obstruct the highways, or at least to arrest them before significant disruption has been caused. The law is uncertain and legislation is urgently needed to clarify it. However, in the meantime it bears noting that while the Ziegler judgment clearly imposes risk, it does not necessarily make it unlawful for police to act swiftly in relation to protestors who block the roads. Ziegler is a judgment not a statute. It clearly establishes that deliberate physical obstruction of the highway is not necessarily an offence, despite the terms of section 137, but it does not constitute a code for future police action. It leaves it to future courts to decide whether any particular protest constitutes an offence under section 137, let alone whether an arrest for a suspected offence is unlawful, which was not a question that the Supreme Court in Ziegler directly addressed. This is not a good state of affairs, but it does not require police to treat Ziegler as a code for future policing. The point is not that police should defy the Supreme Court – of course not – but rather that police forces should not overinterpret the Court’s judgment and take it to settle points that are in fact unsettled.

Importantly, the legal standard for carrying out an arrest is lower than to charge and far lower than to secure conviction. That is, if police arrest protestors immediately, the police may well act lawfully insofar as they reasonably suspect that an offence has been committed – because the protest was intended to cause significant disruption, or was located in such a place as to cause significant harm to the public, or was likely to result in public disorder and breaches of the peace. It is possible that the protestors will be acquitted in due course, which is likely an insoluble problem without remedial legislation. But whether they should be convicted or acquitted will usually turn on fact specific argument about the proportionality or otherwise of a conviction in relation to the protest in question. Police should not arrest protestors if they can see that there would be no prospect of a conviction. But they can (and should) arrest protestors if they reasonably suspect that an offence has been committed, even if this cannot be determined with confidence until trial, at which point the magistrate or judge (or jury) will have to decide whether a conviction would be a disproportionate interference with Convention rights.

In addition, police should recall that failure to respond in time to emergencies, resulting in death, can clearly constitute a breach of Convention rights.64Michael v Chief Constable of South Wales Police [2015] UKSC 2 Thus, police failure promptly to clear the roads, which may delay ambulances, fire brigade or police response to emergencies, risks exposing them to a different ground of legal liability. It follows that it would be a mistake for police forces to consider only the Ziegler risk, which in any case primarily concerns the likelihood of conviction rather than the lawfulness of arrest, given that the law also requires them to act to vindicate the Convention rights of other persons. Furthermore, it is clearly the case that members of the public, frustrated by inaction or delay, are increasingly likely to exercise force to clear the roads themselves. While police might arrest such members of the public, they will have an arguable defence under section 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967, which authorises use of reasonable force to prevent crime. The use of force by members of the public may well be lawful, but it would be much better for police rather than the public to act in order to avoid excessive uses of force or breach of the peace. Police have a good argument to make that they must move quickly to arrest protestors who obstruct the roads in part because delay in making arrests will increase the likelihood that a breach of the peace might otherwise arise. That is, the likely reaction of members of the public to the protest – a reaction that protestors may well intend to provoke – is relevant to whether or not arrests are a disproportionate interference in Convention rights.

In relation to charges of criminal damage, the Court of Appeal’s Colston judgment may minimise the risk that trials will descend into a political circus, in which defendants argue that the importance of climate change justifies their destruction of public or private property. But, in relation to cases in which the damage in question is minor (smashing milk bottles, deflating tyres), it appears the Colston defence is still being run, and there must be a risk that such trials will be very difficult to manage and convictions difficult to secure, despite clear, and sometimes admitted, damage to property and thus the rights of others. It is not at all clear why deliberately damaging public property, which concerns us all, should be subject to a different criminal law standard, but this is likely in view of the law as it currently stands.

In relation to charges of obstructing the highway, unless and until Ziegler is overturned by the Supreme Court or reversed by legislation (as this paper recommends), it is very likely that trials will continue to descend into a fact-specific argument about whether a conviction in each particular case is thought to be necessary in a democratic society. The criminal law in question is not fit for purpose and needs to be revised so that it can be applied swiftly and effectively in order to convict and punish those who choose to obstruct the roads in order to harm others and thus to make their political point. It is perfectly reasonable for the criminal law to tolerate protest that has the unintended side-effect that it slows traffic or causes noise. It is not at all reasonable for the criminal law to license protest that is intended to achieve its effects by disabling the highways, delaying others, and harming social and economic life (and even disrupting other emergency services). While the latter type of protest may not involve acts of violence as such, neither is it peaceful. In one sense it is not even protest. It is direct action, aiming to hurt members of the public and property owners in order to attract media attention and to force the public and our government to comply with their demands if the hurt is to cease. This is nothing like protest as ordinarily understood.

The law as it stands makes it difficult in many circumstances to know whether an arrest will be lawful or, relatedly, to be confident that if certain facts are proved (or admitted) a conviction will be secured in due course. The law should be changed accordingly, as a matter of urgency. Nonetheless, in the meantime police can and should be more assertive in policing protest. The Ziegler case makes policing more difficult, no doubt, because police cannot simply treat deliberate physical obstruction of the highway as an offence and because the prospects of conviction for obstruction are at times very difficult to predict. But it remains open to prosecutors to argue in court that on the facts of this or that case the protestors in question were acting outside the scope of Convention rights (including in attempting to use Convention rights to impede or destroy the rights of others) and should be convicted. Police may lawfully arrest protestors where they reasonably suspect that a later court would conclude that protestors were acting outside the scope of Convention rights. On the facts of the Ziegler case this conclusion was not made out. But again, the Ziegler case is a judgment, not a statute (or a code), a judgment in which the five Supreme Court judges disagreed about how to evaluate the protest in question. There is much room for prosecutors to argue that a conviction in relation to this or that particular protest, in which the whole highway was blocked with a view to distressing or provoking the public, would not be a disproportionate interference in Convention rights.

Note that in acting (jointly) to commit offences of obstructing the highway, public nuisance or criminal damage, protestors likely also commit tortious wrongs, including the tort of unlawful means conspiracy.65Total Network v HMRC [2008] UKHL 19 It would be open to private persons or businesses, or relevant public bodies or government departments, to vindicate their rights in private law against protestors, their organisers and financial backers. The government, local authorities and public bodies (for example the Highways Agency and Transport for London) are, at a time of severe fiscal disruption and budgetary constraints, being put to significant costs by such protests. They should vigorously pursue compensation in the courts for such losses caused. Consideration might also be given, in appropriate cases, to the use of the Attorney General’s traditional power to seek injunctions to prevent public nuisance.66London CC v Attorney General [1902] AC 165

Nothing in the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 addresses the problems to which the Ziegler case gives rise.67These are problems to which Policy Exchange has been drawing attention for some time. See: Richard Ekins, The Limits of Judicial Power: A programme of constitutional reform (Policy Exchange, 1 October 2022); David Spencer, What do we want from the next Prime Minister? Crime & Policing – A force fit for the future (Policy Exchange, September 2022); Richard Ekins, “The Colston trial still leaves questions to answer”, The Telegraph, 21 April 2022; Charles Wide QC, Did the Colston trial go wrong? Protest and the criminal law (Policy Exchange, 13 April 2022); Richard Ekins, “Braverman is right to seek clarification from the Court of Appeal on the Colston case”, Conservative Home, 13 January 2022; and Richard Ekins, “The law is not fit to stop Extinction Rebellion’s street protests”, The Spectator, 28 August 2021. Likewise, the Public Order Bill, which has now made its way through the House of Commons, fails to address the problems in question. Instead, the Bill introduces a number of new offences, each of which is likely to prove unworkable in practice because of the provision each makes for “lawful excuse”, which on the law as it stands (per the Human Rights Act 1998) will simply import the question of Convention rights compliance. (By contrast, clause 9 of the Bill makes very harsh provision in relation to acts of protest, or religious practice, outside abortion clinics, protest that in contrast to obstruction of the highway or criminal damage is in fact genuine protest and does not involve preventing any person from exercising her rights under the law.)

What is required is for Parliament to enact legislation that provides that there is no lawful excuse for obstructing the highway when doing so is —

- designed to intimidate, provoke or inconvenience or otherwise harm members of the public by interrupting or disrupting their freedom to use the highway or to carry on any other lawful activities,68Compare section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2000. The proposed legislation might instead refer to obstruction of the highway that is “intended” to intimidate, provoke or inconvenience, etc. or

- designed to influence the government or to influence the media by subjecting members of the public or their property to a risk, or increased risk, of loss or damage.

Legislation should specify that for all the purposes of Convention rights and the Human Rights Act this provision must be treated as necessary in a democratic society for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. Legislation should make similar provision in relation to criminal damage and other related offences, thus ruling out any defence that one has a lawful excuse intentionally (or recklessly) to damage another’s property in order to make one’s political point.

If legal order is to be restored, it is imperative that protestors who repeatedly obstruct the highways and/or damage property are swiftly arrested, convicted and punished. Magistrates and judges should be imposing severe sentences on repeat offenders who aim deliberately to harm the public by breaching the criminal law, particularly where the breach is intentional and yet results in a not guilty plea, contrary to the traditional understanding of civil disobedience (in which the offender accepts the legitimacy of punishment imposed on him or her). But there must be a strong risk that judicial sympathy for the cause for which protestors act, or even tolerance for the antics of persons from a similar (middle) class background, results in the court imposing unduly lenient punishment.

For this reason, the legislation recommended above should also specify that when sentencing the court shall not regard sincere belief in a cause to be mitigation. The Lord Chancellor should formally request the Sentencing Council to promulgate guidance in relation to the punishment of acts of political protest. It is to be expected that these guidelines would restate the obvious and very well-established point that repeat offenders are to be treated much more harshly than a first-time offender, especially where further offences take place while a person is on bail or otherwise display a brazen contempt for the criminal law and for court orders.

Next chapterThe Policing of Protests

David Spencer

The policing of protests will always be amongst the most challenging of operational policing activities. Over recent years, this has become only more so with a measurable increase in the number of confrontational protests, as well as a change in the applicable criminal law, following the Ziegler judgement, as previously outlined.69D. Bailey, Decade of dissent: how protest is shaking the UK and why it’s likely to continue (January 2020), The Conversation, link Confrontational tactics include activities such as ‘locking on’ (where protestors attach themselves to buildings, the transport network and other structures with glue, chains or D-locks), mass obstruction of the highway and criminal damage by highly motivated protestors.

The current legal framework concerning protest fails to satisfactorily resolve the central question of dividing lawful and criminal activity. This lack of legal clarity has led to a situation whereby the policing of protests is not only challenging, but an activity where the police seem destined to satisfy no-one. However, while the current legal framework may well be unsatisfactory, it is essential that the police do all they can within it to maintain order and deal with those individuals who they reasonably suspect of committing criminal offences. It is clear there are cases where some police forces could be doing so more promptly and more effectively.

The police response: Once officers arrive at the scene of a protest, as with all policing activities, their immediate priority must be to ‘protect life’ by ensuring the immediate safety of the protestors, motorists and wider public. Before making arrests and removing individuals who are obstructing the highway officers should make an assessment of the facts present before they are able to justify an arrest. This will almost always require officers to consider the disruption and potentially to engage the protestors in some form of discussion, albeit given the repeated circumstances of the Just Stop Oil protests this could be completed rapidly. Once officers have completed this process lawful arrests can be made. With upwards of 20 arrests at each scene, the added complication of protestors needing to be ‘de-bonded’ from the carriageway and then needing to be carried away as they refuse to walk to waiting police vans, this frequently means up to 50 officers must be deployed to each incident.

Given the scale of disruption caused by protestors across the capital and elsewhere it is essential that police officers are deployed to protest scenes and take steps to deal with those committing criminal offences as swiftly as possible. Scenes of protestors being permitted to obstruct the highway for extended periods, such as the occupation of London’s Oxford Circus by Extinction Rebellion for five days in April 2019, cannot be repeated. Reviewing the policing of the Just Stop Oil protests suggests that officers are typically taking less than two hours from arriving on scene to making arrests and removing individuals who are obstructing the highway. Comparing this with previous protests, it is apparent that the Metropolitan Police are taking a swifter and more assertive approach than they may have done historically. This is to be welcomed.

However, while some progress may have been made, the Met continues to take an unnecessarily risk-averse approach to the speed of arrests. In addition to an overly risk-averse reading of the Ziegler judgement, as outlined in the previous section, the College of Policing ‘five step-appeal’ model for dealing with individuals who are refusing to comply with officers’ instructions appears to be contributing to the delay in dealing with protestors in a timely manner. Requiring officers to follow each of these steps before taking action, while disruption is mounting around them, does appear to be overly-cautious. This over-abundance of caution is leading to delays in the arrest and removal of offenders and could be overcome with a more proportionate approach.

College of Policing’s ‘Five Step Appeal’ Model70College of Policing, Conflict Management Skills, link

- Simple appeal – ask the person to comply with your request.

- Reasoned appeal – explain why the request has been made, what law (if any) has been broken, and what has caused the request.

- Personal appeal – remind the person that they may be jeopardising things that are high priorities to them (eg, loss of free time if arrested, loss of money, loss of income, possibility of a criminal record, loss of respect of their partner and family).

- Final appeal – tell the person what is required and use a phrase that means the same as the following: ‘Is there anything I can reasonably do to make you cooperate with me/us?’

- Action – reasonable force may be the only option left in the case of continued resistance.

The level of complexity and risk taken by officers dealing with confrontational protests, both on the ground and those leading policing operations, should not be under-estimated. The risk of officers receiving vexatious complaints from protestors poses a considerable occupational hazard. It is essential, in order that officers can be confident in dealing with protests, that the College of Policing and Chief Constables make far clearer, to both officers and the public, that where officers act in good faith they will be supported.

Where there are delays in officers clearing the highway, there is a particular concern that members of the public may elect to intervene themselves71See for example Twitter, @juststopoil, link. Scenes of apparently angry and frustrated members of the public remonstrating with and dragging protestors from the road have become all too common. The police themselves have now called for members of the public not to intervene, for fear of the escalating tension between protestors and the public72Metropolitan Police Service, Statement regarding ongoing protests across London, link.

In addition to the risk that members of the public and protestors may cause injury to one another, members of the public intervening may find themselves be at risk of prosecution. Although members of the public may have a lawful defence by claiming that they were attempting to prevent protestors from committing a criminal offence,73Under Section 3 Criminal Law Act 1967 if their actions are determined to be disproportionate prosecutions and convictions may well follow. During the October 2021 protests by Insulate Britain a motorist used her Range Rover to drive into protestors, claiming she ‘nudged them’ in an effort to move protestors from obstructing the highway.74The Sun, 6th May 2022, link She subsequently pleaded guilty to a charge of Dangerous Driving, was banned from driving for a year and instructed to complete 20 days of community service.

Given the clearly mounting tensions on London’s streets, there is little doubt that such situations pose a significant risk to all parties. The police must act quickly to ensure they are avoided.

It is also clear that not all police forces are following the Met’s lead in dealing with protestors more quickly. While the Met may typically be dealing with the removal of protestors and obstructions within (the still too long) two hours, the failure of Essex Police to arrest two protestors who had suspended themselves above the Queen Elizabeth II bridge for two days, leading to the closure of the Dartford Crossing, suggests that a swift and assertive approach is not being universally applied. Given the Dartford Crossing is the only means of crossing the Thames east of London, there can be little doubt that its closure for any period of time would lead to significant disruption, yet the protestors’ actions led to this critical transport infrastructure being closed for almost 48 hours. In future all police forces must follow the path of speedy and assertive response to protests which the Metropolitan Police has started to chart under its new Commissioner.

The public’s confidence in policing: The public’s confidence in whether the police are doing a good job is more than just a glorified customer satisfaction rate. It is central to the British concept of “policing by consent” and significantly impacts whether the police can be effective at the core policing mission to fight crime and keep the public safe. Where people have higher trust and confidence in the police they are more likely to come forward with information or intelligence, are more likely to obey the law, and are more likely to defer to police authority. Yet the policing of high-profile protests, particularly given the confused legal framework that police officers are operating within, is putting the public’s confidence in the police at risk.

Polling conducted last year showed by an overwhelming margin that the public did not support similar protest action by Insulate Britain in October last year.7573% of the public opposed or strongly opposed Insulate Britain protests in October 2021(1667 respondents), YouGov, link In light of recent scenes of ambulances and fire engines being prevented from reaching emergencies and members of the public forcibly moving protestors from blocking roads, it is unlikely that the standing of protestors in the eyes of the public will have since improved. Given previous polling and recent events there are indications that the public’s perception is that police inaction is at least partially responsible for the disruption being caused. If this is the case, it is highly likely to be having an impact on the public’s broader confidence in the police.

In contrast, a perception of over-reaction by the police also poses considerable risk to the public’s confidence in policing. This was perhaps most clearly seen in the policing of the vigil at Clapham Common on Saturday 13th March 2021 following the murder of Sarah Everard. The vigil itself led to large numbers of people gathering on Clapham Common and the police making a small number of arrests. A subsequent inspection by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services stated that, “the examination and analysis of body-worn video presented a true picture of the disorder, and the commendable restraint shown by police officers. This entirely contradicted the false assertions of police violence on that occasion”76Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (2021), State of Policing: Annual Assessment of Policing in England and Wales, link. Despite this they also concluded that, “media coverage of this incident led to what many will conclude was a public relations disaster for the Metropolitan Police. It was on a national and international scale, with a materially adverse effect on public confidence in policing”77Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, An Inspection of the Metropolitan Police Service’s policing of a vigil held in commemoration of Sarah Everard (30th March 2021), link.

Given criticism seems to follow the police for being either too heavy-handed or too soft in the policing of protests, it would perhaps be unsurprising if they were tempted to ask whether they are ‘damned if they do and damned if they don’t’. Even were the legal framework meticulously crafted, the policing of protests is such that this may always be the inevitable path that police leaders must chart. However, the uncertainty provided by the existing legal framework, as previously outlined, substantially increases the risk that the public’s confidence in the police will be negatively impacted whatever action they take.

In order to retain the public’s confidence in policing, officers must not only act swiftly and assertively when confronted with protests, but they must also communicate that they are doing this to the public. The police should publicise, for every protest they attend:

- the time they arrive on scene,

- the time arrests begin,

- whether protestors were ‘glued-on’,

- the time it took to remove protestors,

- the number of arrests made, and

- the details of charges along with the basic biographical details of those charged.

- Impartiality and professionalism: The perception that an officer’s operational decision making, such as whether to arrest someone, might be influenced by a partisan political view has the potential to be hugely damaging to the public’s confidence that policing is being done fairly. The current protests pose a particularly acute risk where there may be a perception that the police may well be willing to act swiftly and robustly in response to ‘have-a-go’ heroes intervening, while failing to do the same in relation to the protestors themselves.

To prevent any risk of officers being accused of failing to act impartially, they must always act with the utmost professionalism. There is a clear difference between officers discharging their duty of care once arrests have been made, for example by providing protestors with water, and suggesting that they sympathise with or are otherwise willing to indulge lawlessness, as for example dancing with protestors who may be committing unlawful acts, as was observed during the 2019 Extinction Rebellion protests on Oxford Street, London.

Even if actions such as police officers dancing with protestors have, in reality, been very rare, they have grown in prominence given that officers’ actions are now frequently broadcast widely through social media78See for example The Times (10th June 2020), link. Recent polling has found that, “the public were almost twice as likely to agree than disagree with the statement that ‘the police are more interested in being woke than solving crimes’”79L. Tryl, ‘The police must show they care more about tackling crime than being woke, CapX’ (23rd August 2022), link. While this may be a grossly unfair distortion of what police officers engaging with the public are attempting to achieve at the policing of protests, the potential prominence of this perception is reflective of the scale of the challenge for modern policing.

To maintain the public’s confidence in policing, officers policing protests must always act impartially in service of the law and with the utmost professionalism. To support officers in dealing with the increase in confrontational protest, police officers would benefit from additional training and greater clarity from leaders, relating to policing protests with professionalism and impartiality.

Conclusion: Occurring in full view of the press, social media and the public, police forces cannot afford to get the policing of these events wrong. The impact of these protests is considerable. To enable the rapid deployment of large numbers of officers to protests, the Metropolitan Police Service has, throughout October 2022, been required to remove hundreds of officers every day, equal to nearly 8,000 frontline policing shifts over the course of the month, from their normal duties, in communities across the capital.80Metropolitan Police Service, Statement regarding ongoing protests across London, link There can therefore be no doubt that the protests are having a knock-on impact on the Met’s ability to maintain public safety and tackle crime elsewhere across London. This cannot be in the wider public’s interest.

It is incumbent on the police to act within their best interpretation of the law. That requires police officers to be well trained, led by experienced public order commanders and to possess the courage necessary to deal with disruptive and violent individuals. Officers must be willing to act as swiftly and assertively as the law allows. There is currently evidence to suggest that forces and officers can go further in this regard, particularly given the current guidance issued by the College of Policing for dealing with the conflict caused by confrontational protestors.

It should not be necessary for police forces and individual officers to have to clean up where the legislature and the courts have failed to act. Yet the current combination of legislation, case law and formal guidance is limiting policing from being as effective as it might be in successfully navigating these highly challenging events. Parliament must act.

Next chapterPolicy Recommendations

- Parliament should enact legislation reversing the effect of Ziegler and thus providing that there is no lawful excuse for obstructing the highway when doing so is —

- designed to intimidate, provoke or inconvenience or otherwise harm members of the public by interrupting or disrupting their freedom to use the highway or to carry on any other lawful activities; activities, or

- designed to influence the government or to influence the media by subjecting members of the public or their property to a risk, or increased risk, of loss or damage.

- This legislation should specify that for all the purposes of Convention rights and the Human Rights Act this provision must be treated as necessary in a democratic society for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

- Legislation should make similar provision in relation to criminal damage and other related offences, thus ruling out any defence that one has a lawful excuse intentionally (or recklessly) to damage another’s property in order to make one’s political point.

- All police forces must act with speed when protests occur including making swift arrests when the law is broken and preventing criminal offences at the earliest opportunity.

- The College of Policing should overhaul its Conflict Management Model which appears to be delaying police officers from taking swift action to deal with protests.

- The police should provide detailed public information on every protest they attend to demonstrate they are acting within the law, assertively and with appropriate speed.

- All police officers should receive training relating to the policing of protests with professionalism and impartiality.

- Given the presence of crowdfunding sites assisting activists who are fined for criminal offences, magistrates and judges should consider carefully whether fines are an appropriate penalty in cases involving protestors.

- Just Stop Oil protestors have been encouraged to sign paperwork committing them to breaking the law, and that they will not back out from attending protests. The police and Crown Prosecution Service should investigate whether agreeing such “contracts” itself represents a criminal offence

- The current wave of protests raises a clear problem of repeat offences, committed at times by repeat offenders. With activists holding rolling protests in a short period of time, it is now necessary to review bail and sentencing guidelines, to ensure they are fit for the changed circumstances. Allied to this, the use of injunctions against Insulate Britain protestors who repeatedly protested around the M25, should be repeated more widely.

- Parliament should enact legislation that specifies that when sentencing offenders for obstructing the highway, or other relevant offences, the court shall not regard sincere belief in a cause to be mitigation.

- The Lord Chancellor should formally request the Sentencing Council to promulgate guidance in relation to the punishment of acts of political protest. It is to be expected that these guidelines would restate the obvious and very well-established point that repeat offenders are to be treated much more harshly than a first-time offender, especially where further offences take place while a person is on bail or otherwise display a brazen contempt for the criminal law and for court orders.

- Private persons or businesses, relevant public bodies and government departments should consider vindicating their rights in private law against protestors, their organisers and financial backers. In particular, the government, local authorities and public bodies (for example the Highways Agency and Transport for London) should vigorously pursue compensation in the courts for the losses they have suffered.