Authors

Content

Executive summary

Westminster is the physical heart of the British state, a centre of the Christian faith, and the symbol of Britain to the world. Nowhere else in Europe, with the possible exception of the Eiffel Tower, is more famous, or more emblematic of its nation. Nowhere else combines those supreme symbolic qualities with being the place where actual power resides and the highest work of government is done.

Yet what should be a showpiece has declined into a degree of squalor and disorder. Windows of the great public buildings, broken by protestors, are splintered or patched with duct tape. Anarchist and anti-police graffiti is painted on those buildings’ walls; some of it has been there for more than two years. Urine trickles from the corners.

Protestors have privatised the pavement, illegally and for hours blasting out amplified music that hinders the often critical work being done in the offices along Whitehall. Skateboarders use the steps of the parliamentary building, Portcullis House, as a regular practice area. The experience for visitors is dispiriting and may include being cheated by con-men on Westminster Bridge.

Crowds of people press round the entrances to Parliament, banging on the sides of MPs’ cars as they drive in. Parliament Square is a three and four-lane traffic roundabout. MPs are verbally abused, occasionally chased. Some parliamentarians say they feel physically afraid to leave the building. People coming to see their MPs, or keep appointments in government buildings, can’t always get in.

“Broken windows” theory says that visible signs of vandalism, anti-social behaviour and neglect encourage further crime and disorder. It appears to hold true amid the literally broken windows of Westminster.

Between 2013/14 and 2021/22, this study finds, violent crime in the quarter-mile immediately around Parliament has risen by 168 per cent, against a 47 per cent rise in the borough of Westminster as a whole and a 67 per cent rise in London. Public order offences have risen by 252 per cent – three and a half times – versus 75 per cent in the borough as a whole and 93 per cent in London.1Figures extracted from UK Crime Stats website, https://ukcrimestats.com/members/heatmap/heatmap_dev.php. Offences, particularly of violence, have fallen recently, but remain at very high levels.

Even without becoming a victim of any of these crimes, someone taking the ten-minute walk from, say, Waterloo Station to Parliament could easily pass as many as half a dozen breaches of the law, from the illegal vendors and confidence tricksters on the bridge, to the pedicabs blocking the traffic, to the bellowing loudspeakers of the protestors, to the people camping in the shop doorways. None individually is serious, but they have an important cumulative effect.

The area is a mess because its governance is a mess. Control of the public spaces around Parliament is split between eight different bodies, often with different policies. Parliament Square alone is controlled by three different official agencies. The government publishes a map to show you which bits are whose, and where certain restrictions apply.2https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/364469/Parliament_Square_Guidance.pdf, page 10 Symbolising the muddle, key details on it are wrong, so no wonder the policing of the area is a little confused.

But the area is also a mess because of a lack of confidence and consistency by those in charge. There is of course no right to urinate in the street, or cheat tourists, or vandalise, but the authorities often seem unwilling to challenge such practices. The law is often ignored around the very building where the laws are made.

There is a right to protest – or rather, there are rights to freedom of speech and assembly, including around Parliament, which this paper supports. But there is an important, if not always recognised, distinction between protest that happens to cause disruption to others (for instance, because many people have gathered in the same place) and protest that aims to cause disruption to others as a principal objective (for instance, by a handful of people blocking a road, or using amplification to make it difficult or impossible to work nearby.)

The disruption caused by demonstrations of thousands is part of the price of democracy. But we question the way in which much smaller numbers of people are regularly, repeatedly and illegally allowed to cause disproportionate disruption, sometimes risk, and sometimes fear to others. The right to protest has sometimes been privileged over other rights, such as the rights of others to move freely, to work, to speak, and even to be safe. The authorities should act more strongly against protest whose principal aim is to annoy, inconvenience or intimidate, rather than to convey a message.

Yet if enforcement is inconsistent, another part of the problem is that decisions by the courts and Parliament have made consistent enforcement harder. Over the last two decades the law has vaccillated. The “controlled area” around Parliament – where, for instance, loudspeakers and structures are supposed to be banned – has been reduced, then enlarged, then cut to almost nothing, then gradually enlarged again. But it is still smaller than it was – it excludes, for example, the whole of Whitehall (Parliament Street, which joins Whitehall to Parliament Square, is included, however).

The Supreme Court’s Ziegler judgement, which says that those obstructing the road should not be convicted if it was a disproportionate interference with their rights of protest, has made it more difficult for the police to act. Amendments currently in Parliament seek to deal with this issue.

Many of these problems were raised in a report by Parliament’s own Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR), more than three years ago, after high-profile mobbing incidents of MPs in the area.3https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf Some things have changed for the better. The protestor camps in the middle of Parliament Square went in 2013. In 2016, a new pedestrian crossing allowed the square to be reached, and reclaimed, by the public. More recently, there appears to be slightly more proactive policing in Westminster. But not enough has changed, as the crime figures show. The government took almost 18 months to respond to the JCHR report and much of its response is non-committal.4https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5160/documents/51000/default/ For a full discussion, see later chapters.

There are plans to dramatically improve at least the physical environment, removing traffic from two sides of Parliament Square and making the Palace of Westminster safer from terrorist attack. But they have been drawn up almost in secret; and they are stalled because the various official bodies are quarrelling about who should pay for them.

In all these ways, too, Westminster symbolises Britain.

Next chapterRecommendations

- As recommended by Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights, there should be zero tolerance for obstruction and intimidation around Whitehall and the Palace of Westminster (or for vandalism, illegal street trading or anti-social behaviour.) Any offenders should be immediately asked to stop, then arrested if they do not.

- As also recommended by the Joint Committee, there should be a statutory duty on police to protect the UK’s democratic institutions and to protect the right of access to the parliamentary estate for those with business there.

- Westminster City Council should take out a wider Public Space Protection Order, covering anti-social behaviour in the whole area round Parliament (there is one covering illegal gambling on Westminster Bridge, though it is not consistently enforced.) Lambeth Borough Council should do the same on its half of the bridge.

- The “controlled area” for protests should be restored to what it was until 2011, namely within broadly one kilometre of Parliament, covering all the main departments and Downing Street. Alternatively, the pre-2005 Sessional Orders, abandoned by Parliament because they lacked legal force, could be revived by passing new legislation to give them legal force.

- Demonstrations within the controlled area should still be allowed, but normally for shorter periods, longer at weekends, and in a way that allows the working life of the area to continue. Amplification and marches on weekdays and the erection of structures should not normally be allowed. This preserves the right of protest while upholding the rights of others to go about their business normally.

- The law should be consistently and predictably applied, including to professional or habitual demonstrators.

- The Public Order Bill currently before Parliament should be amended to reverse the effects of the Ziegler judgment, as recommended in previous Policy Exchange reports.

- It is not clear why events with no relationship to government policy such as celebrations of other countries’ national days – need to take place in Westminster at all, as opposed to other places, such as Trafalgar Square.

- For the purposes of authorising public gatherings, the whole controlled area should be brought under the control of one authority, the Parliamentary Security Department, responsible to the democratically elected Commons and Speaker. The roles of the Greater London Authority, Westminster City Council and (in Parliament Square) the Royal Parks in authorising public gatherings should end.

- The intermittent closure or fencing off of public spaces, such as College Green, to the public in order to pre-empt disruptive and illegal protests is wrong and should end. Authorities should target and interdict any law-breaking protestors rather than denying law-abiding citizens access to public land.

- A dedicated team of police officers should patrol the area on foot, bicycle and motor vehicle to maintain public order and to intercept unauthorised demonstrations before they can take hold.

- The rules should be made clear (to protestors, workers in the area and all those charged with enforcement) by being laid down in simple terms on a website and on noticeboards. Current information is confusing and sometimes incorrect.

- Parliament and government departments should more actively use civil sanctions against individuals who persistently harass and damage – including seeking community protection notices, injunctions and monetary recompense. Anyone convicted of a criminal offence of harassment should normally be placed on a Criminal Behaviour Order. Equipment confiscated after being used illegally should not be returned.

- The owners of the area’s buildings and structures – nearly all of them official bodies – should immediately repair broken windows and properly remove graffiti. They should ensure that each building is inspected every day and that damage is immediately and fully rectified.

- The plans for part-pedestrianising Parliament Square, while maintaining vehicle access to Parliament, should be taken forward without delay.

One day in Westminster

Directly opposite Downing Street, the antivaxxers have taken over part of the pavement, erecting a semi-permanent, eight-foot-high wooden shack to store their camping chairs, generators and ladders out of sight of the police. At least they only want to try the chief medical officer for murder and treason. Let us hope no terrorist realises that such a structure could be used to hide a bomb. (As this paper went to press, the structure was removed.)

On Westminster Bridge, the pavement is blocked with crowds of tourists gathered round illegal scam games and unlicensed hot chestnut salesmen. The pedestrian crossing is blocked by a pedicab parked on the pavement. The bus lane is blocked by three more pedicabs and a van selling £7 hotdogs. The cycle lane is blocked by a line of customers waiting to buy the hotdogs.

Halfway between the two places, the traffic island outside the HMRC and Treasury building has been taken over by sometimes dozens of protestors and their sound equipment, there every week. Pedestrians must squeeze past them to cross. The railings have been turned into a political advertisement hoarding. The amplifiers have been playing the Darth Vader theme and a song about “sex offender Tories” on loop, loudly, for the past four hours. A guy with an EU badge and My Little Pony hair is singing along, waving a plastic chicken.

Graffiti, only half-heartedly cleaned off, is still visible. The letters ACAB, “all cops are bastards,” can still be seen over the tube station entrance at the corner of Parliament Street and Bridge Street, two and a half years after they were sprayed there by the Black Lives Matter protestors. The base of the Boudicca statue on the Embankment is covered in scribbles. The anarchist symbol, and a large phallus, are sprayed on the front of the parliamentary office at Portcullis House. Six of this building’s foyer windows – broken by demonstrators, and not repaired – are patched with duct tape. Two more are cracked and splintered. They have been like that for more than a year.

And this is just a normal day. On other days, the whole of Whitehall has been turned into a campsite by eco-activists, living for almost a week in dozens of small tents pitched in the middle of the street. Protestors have played loud music, late at night, for hours outside the Downing Street gates to keep the prime minister and his family awake. Animal rights devotees have climbed up the side of the Home Office, past the Home Secretary’s window, and covered it with a banner demanding “investment in a plant-based future.”

Entrances to Parliament are too often blocked, with MPs and peers sometimes diverted to other entrances or unable to enter the building at all. Peers and MPs have been asked by parliamentary staff to complain to the authorities, with senior officials of parliament saying that the police in Westminster feel constrained from intervening to prevent obstruction.

It is now routine for prime ministerial statements outside Number Ten to be half-drowned out to those listening in the street itself by loud music and chanting from mobs gathered outside the gates; TV viewers don’t fully appreciate this because of the effectiveness of the directional microphones. And it is quite common for crowds outside the gates to force the lockdown of the street. Visitors cannot enter, and the staff cannot leave, or must use other exits.

The thought occurs: if the authorities cannot maintain order in SW1, where can they maintain it?

Next chapterA disturbing picture on crime and disorder

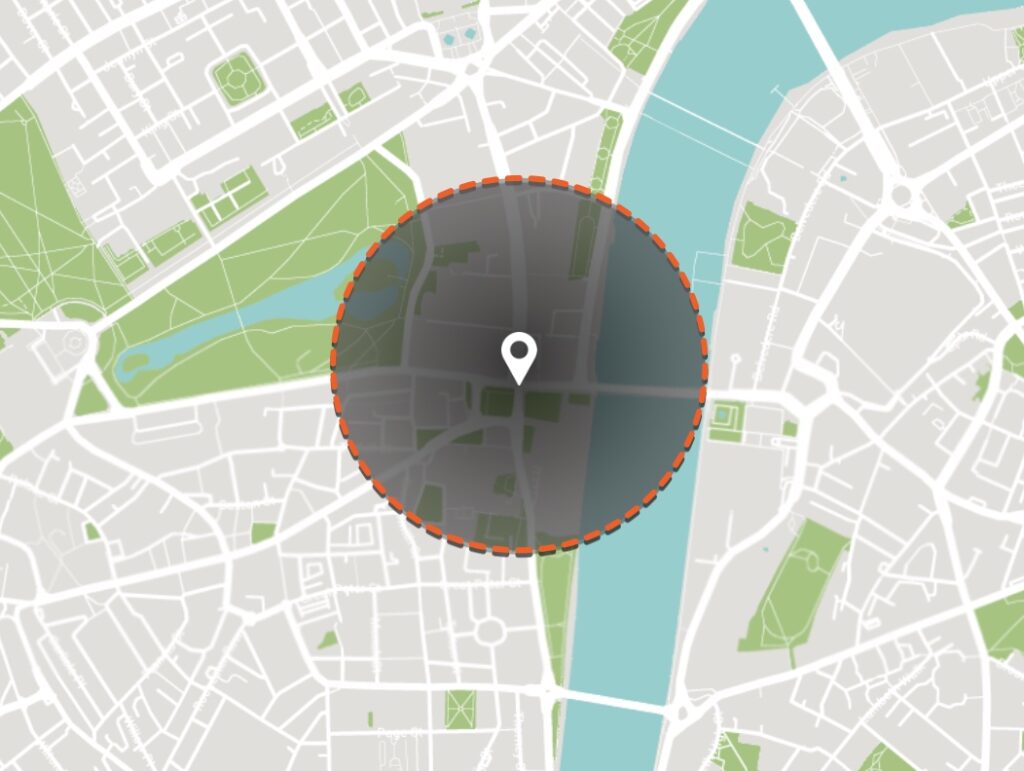

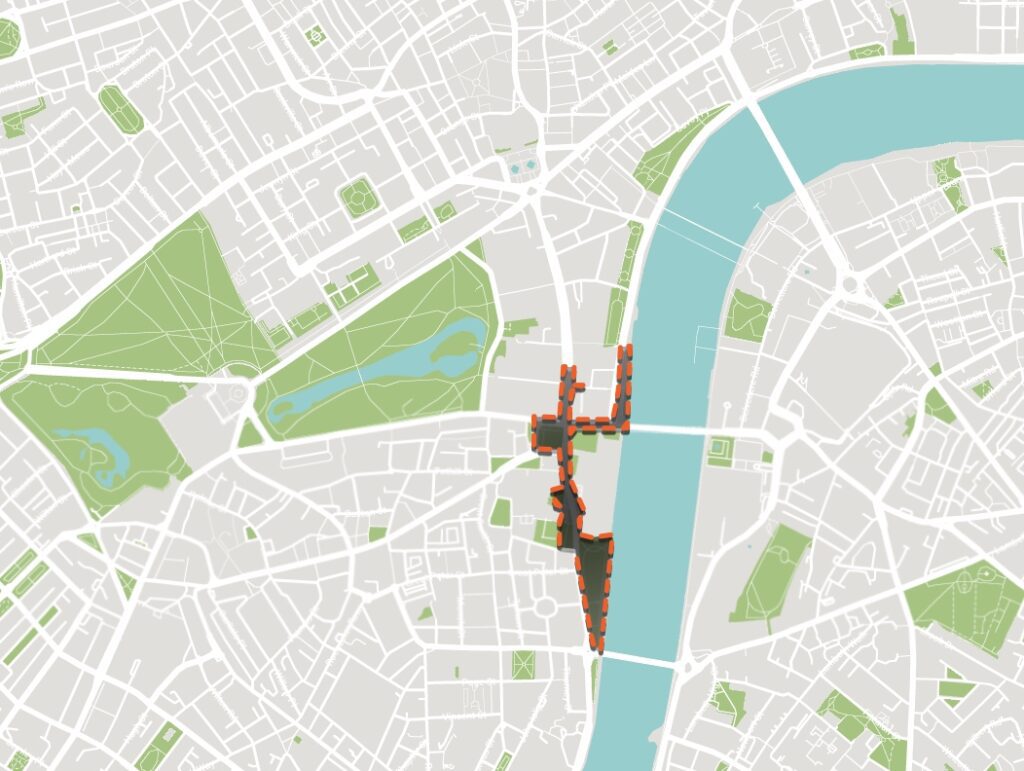

We used the UK Crime Stats website to generate records of crimes committed up to 31 August 2022 within a quarter-mile radius of postcode SW1A 2JX, the parliamentary bookshop on the corner of Parliament Street and Bridge Street.5https://ukcrimestats.com/members/heatmap/heatmap_dev.php – entering “Postcode 1/4 mile radius” and postcode SW1A 2JX. The area includes the whole of Parliament Square, the Palace of Westminster, and Whitehall as far as Horse Guards (see map below). The bookshop is across the road from Parliament and was chosen over the Palace of Westminster’s own postcodes (SW1A 0AA and SW1A 0PW) because a quarter-mile radius of those postcodes includes areas on the other side of the Thames.

Quarter mile radius of SW1A 2JX

Between 2013/14 and 2021/22, violent crime in this area rose by 168 per cent, against a 47 per cent rise in the borough of Westminster as a whole and a 67 per cent rise in London. Public order offences have risen by 253 per cent – three and a half times – versus a rise of 75 per cent in the borough as a whole and 93 per cent in London.6Figures extracted from UK Crime Stats website, https://ukcrimestats.com/members/heatmap/heatmap_dev.php – entering “Postcode 1/4 mile radius” and postcode SW1A 2JX.

We also extracted figures for the census “lower super output area” covering Parliament, Westminster 020C. These show a 146 per cent rise in violent crime and a 210 per cent – more than eight-fold – rise in public order offences since 2013/14.7https://www.ukcrimestats.com/LSOA/E01004733 This area, about a quarter of a council ward, is bigger and not quite as exclusively governmental. But it is still overwhelmingly composed of the government area and includes some flashpoints, such as the Home Office, MI5, and DEFRA, which aren’t within the quarter-mile radius.

Offences in both geographies rose to high levels in 2018/19 and have remained high since, though have declined, particularly violence, from their 2018/19 peak. Some of the rise (particularly in 2019, when concern at intimidation of MPs was at its height) may have been because policing intensified, and more offences came to police attention. But this is unlikely to be the whole reason for such big and sustained increases.

Lower super output area, Westminster 020C

Crimes within a quarter-mile radius of SW1A 2JX (corner of Parliament Street and Bridge Street)

| Violent | Public order | |

| Sep 21-Aug 22 | 182 (+168%) | 67 (+253%) |

| Sep 20- Aug 21 | 199 | 58 |

| Sep 19- Aug 20 | 210 | 64 |

| Sep 18-Aug 19 | 364 | 81 |

| Sep 17-Aug 18 | 155 | 18 |

| Sep 16-Aug 17 | 159 | 35 |

| Sep 15-Aug 16 | 147 | 38 |

| Sep 14-Aug 15 | 112 | 35 |

| Sep 13-Aug 14 | 68 | 19 |

(figures in brackets are change since 2013/14)

Source: UK Crime Stats8https://www.ukcrimestats.com/members/heatmap/heatmap_dev.php Entering “Postcode 1/4 mile radius” and postcode SW1A 2JX

Crimes in lower super output area “Westminster 020C” (figures in brackets are change since 2013/14)

| Violent | Public order | |

| Sep 21-Aug 22 | 244 (+146%) | 90 (+210%) |

| Sep 20- Aug 21 | 295 | 90 |

| Sep 19- Aug 20 | 316 | 100 |

| Sep 18-Aug 19 | 430 | 106 |

| Sep 17-Aug 18 | 319 | 51 |

| Sep 16-Aug 17 | 254 | 68 |

| Sep 15-Aug 16 | 184 | 47 |

| Sep 14-Aug 15 | 167 | 42 |

| Sep 13-Aug 14 | 99 | 29 |

Source: UK Crime Stats9https://www.ukcrimestats.com/LSOA/E01004733

Westminster borough as a whole

| Violent | Public order | |

| Sep 21-Aug 22 | 10040 (+47%) | 2929 (+75%) |

| Sep 13-Aug 14 | 6807 | 1672 |

Met as a whole

| Violent | Public order | |

| Sep 21-Aug 22 | 257649 (+67%) | 59257 (+93%) |

| Sep 13-Aug 14 | 154226 | 30690 |

Next chapter

Both political and non-political lawbreaking is a problem

Significant illegal street-trading and confidence trickery also occur on Westminster Bridge. It is described by a local council report as a “persistent and continuing” problem which has generated more than 1000 calls to police in the last three years, even with the disappearance of tourists during covid. It involves “large groups with upwards of 100 known individuals operating on the Bridge at any given time” and some victims, the council says, have had “several hundred pounds stolen.”10https://www.westminster.gov.uk/media/document/street-gambling-order—pspo A previous version of the report said this activity was directly responsible for a quarter of notifiable offences on the bridge.

The usual trick is the “cup and ball” game, which deceives tourists that there is money to be made by betting on the position of a ball concealed under one of three cups. In practice, the game is unwinnable because the gang can place the ball under whichever cup the player has not bet on. As well as the public order and crime aspects, it is obviously not desirable that being cheated is some visitors’ main experience of the area.

Westminster council has had a “public space protection order” (PSPO)banning street gambling on Westminster Bridge since 2016. This upgrades the level of fine which can be given for the (already illegal) activity. Some success was initially achieved, with police boasting that by 2017 the practice had been “all but eradicated” and winning an international award for their work.11https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/17-01.pdf Since then the problem has returned and the PSPO is not being consistently enforced.

Half the bridge comes under a different council, Lambeth, which also had a PSPO to tackle this activity. However, Lambeth’s order expired in October 2022 and has not been renewed. According to Westminster, Lambeth “intend to reintroduce the PSPO although a timeline for this not yet known. Lambethhave cited challenges due to other priorities and resourcing as well as organisational changes which are ongoing as the reason for the delay.”12https://www.westminster.gov.uk/media/document/street-gambling-order—pspo

Multiple ice-cream vans park illegally in the bridge’s bus lane or on thepavement, blocking both the bus lane and the segregated cycle lane next to it (customers of the vans step or queue across the cycle lane, risking bikes crashing into them). The problem has existed for more than ten years; in 2012, an illegal van was seized and crushed, but again this appears to have been a one-off. More recently, two traders have been prosecuted. Local cyclists say police have told them this year that they can only issue each van with one fine every 24 hours for stopping in a bus lane, which is treated by the operators as simply a cost of doing business.13https://www.reddit.com/r/londoncycling/comments/w1e7zr/comment/igk3ky9/ The Met said in June that they were “working on a long-term solution as [the fines] clearly do not deter them.”14https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-61879138 Eight months later, they are still working and the vans are still there. Numerous other street traders also operate on the bridge, including hot chestnut and flower sellers. None had licences when approached by the author.

We recommend that the PSPO for illegal gambling should be extended to the whole of the (enlarged) controlled area and cover all forms of anti-social behaviour. Parliament and the councils should consider employing more civilian wardens to deal with non-political disorder (a few are already employed by the GLA), filling gaps in the police presence.

Dealing effectively with low-level nuisance and lawbreaking is a matter of consistency and repetition, but current efforts appear sporadic and unsustained. Seizing illegal vehicles which cause danger to others should happen every day until it stops, not once every ten years.

Next chapterProtestors’ rights versus other people’s rights

The role of liberal democracy has often been described as being to reconcile conflicting interests and rights. There are obvious conflicts between people’s right to protest – which can, and these days often does, involve disruption – and other people’s rights to go about their work and lives unimpeded.

In Westminster this is particularly acute. It engages not just the rights of the 20,000 people working there, the thousands of bus passengers and drivers passing through each hour and the several hundred residents – but broader public interests, affecting the welfare and safety of millions, because of the work done in the offices worst affected by protests.

That includes protecting national security (in the Cabinet Office and Ministry of Defence, on Whitehall); crisis management, emergency planning and the protection of key infrastructure (the Cabinet Office again); fighting tax evasion and raising the money to pay for public services (HMRC, on Parliament Street); and holding the state to account (MPs, peers, parliamentary committees and shadow ministers in the buildings overlooking Parliament Street and Bridge Street).

This is nationally critical work and there is a clear public interest in allowing it to be done well, without constant distractions and interruptions. In practice, the offices are not fully soundproofed, noise can be heard and it can be distracting. Broadcast interviews – whose aim, again, is to perform a public service, holding power to account and telling voters what is being done in their name – are also regularly interrupted by protestors shouting or playing music over them.15https://order-order.com/2022/07/07/farce-reaches-fever-pitch-on-college-green/ It is an attempt to deny people who the protestors dislike another right, their right to speak.

If a protest attracts mass numbers, it is perhaps fair for it to dominate central London for a time, provided the rules are observed. But we question the way in which much smaller numbers of people are repeatedly allowed to cause disproportionate disruption, risk, and sometimes fear to others, day after day and week after week.

There is a distinction between protest that happens to cause disruption to others (for instance, because many people have gathered in the same place) and protest that aims to cause disruption to others as a principal objective (for instance, by a handful of people blocking a road, or using amplification to make it difficult or impossible to work nearby.)

The best-known professional protestor, Steve Bray, does observe some limits – he will follow politicians16https://order-order.com/2021/09/10/senior-minister-tells-steve-bray-to-fk-off/, harangue them, film them17ibid, accost them outside pubs18https://order-order.com/2021/06/17/watch-in-full-lee-anderson-mauls-steve-bray/, and shout “Tory scum” at them19https://order-order.com/2022/06/28/watch-police-threaten-to-arrest-steve-bray/ but not actually physically assault them – and there are differing views on whether his behaviour constitutes harassment. But there is a relationship between this sort of protest, the general atmosphere around Parliament, and the othering and dehumanisation of political opponents. One of Mr Bray’s placards asks: “Who doesn’t detest Tories?”

Free speech rights are not unqualified, and should not be exercised in a way that prevents others enjoying their rights. There is a temptation in some quarters, not all on the left, to claim or even celebrate Mr Bray and others like him as harmless, if annoying, British eccentrics. But they are not harmless.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights’ view (not of Bray specifically) was that while “there must be a high level of protection for political speech, and politicians should accept challenge…the current assumption that it is legitimate to speak to and about politicians in a way which would not apply to ‘ordinary people’ should be challenged… Speech or behaviour which would be considered intimidating or abusive if directed toward an ordinary member of the public should not be acceptable if directed toward an MP or his or her staff.”20https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf Many hold to the mantra that any “non-violent protest” is acceptable. But though following someone and screaming abuse at them, as some protestors do, may not be violent, it is surely not acceptable either.

The emerging field of “acoustic jurisprudence” holds that excessive noise can breach a person’s rights. It was developed initially against the police use of equipment such as the Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD), which can be used both as a loud public address system or to emit high-frequency noise to disperse crowds, which can also cause pain, disorientation, and injury. British police have not used the devices, though the Ministry of Defence purchased them ahead of the Olympics. A less powerful device, the Mosquito, which emits a sound wave irritating only to young people’s acute hearing, has been installed in some places to deter loitering by teenagers. Some groups have attempted to bring cases against institutions which emit high noise levels and it is possible that similar arguments could be used against loud and repeated protests in a single concentrated area.

There is also a risk of other harms. In an emergency, crowds of people and street closures make it more difficult for help to arrive in time. Westminster is one of the most terrorist-threatened places in Britain. Though this has not yet happened, demonstrations, particularly involving the erection of structures, could unwittingly provide cover for terrorists – who have attacked the area at least ten times over the years, most recently in the 2017 attack by Khalid Masood, killing five people and injuring almost 50, and the 2018 attack by Salih Khater, injuring three people.

It is puzzling that in an area where every manhole has been sealed and every wastebin removed a wooden structure large enough to conceal a powerful bomb was allowed to stand opposite the entrance to Downing Street for months; and that in 2019 protestors were allowed to pitch tents for days in Whitehall and Horse Guards Road, feet from the windows of government departments and the PM’s flat.

Against all this is the public interest in citizens’ right to protest against the government, including in the place where it does its work. The fact that an act of protest is annoying or offensive to others is not itself a reason to suppress it. But if a protestor’s principal aim is to annoy, offend or abuse, that is a reason for the law not to protect his or her freedom to act.

It is perhaps worth asking what political message playing the Darth Vader march in Whitehall seeks to convey, what change it demands, and whether anyone will actually make that change as a result of hearing it, or just close the window and speak more loudly?

Currently, the right of protest has been privileged over the rights of others to work, to move freely, to be safe and even in some cases (through the interruption of broadcast interviews) to speak. But the two sets of rights, both of them important, can be reconciled. The proposals in this paper represent a rebalancing which protects protestors’ rights while reducing their infringement of other people’s rights.

We recommend that demonstrations within the controlled area should still be allowed, but normally for shorter periods on a working weekday, longer at weekends, and in a way that allows the working life of the area to continue. Amplification and marches on weekdays and the erection of structures should not normally be allowed. This preserves the right of protest while upholding the rights of others to go about their business normally.

The law should be consistently and predictably applied, including to professional or habitual demonstrators. The Public Order Bill currently before Parliament should be amended to reverse the effects of the Ziegler judgment, as recommended in previous Policy Exchange reports.

| The “contentious” Cenotaph |

| A Freedom of Information Act request to the Metropolitan Police shows the force has produced a list of “contentious statues,” including the Cenotaph. The majority are in the Westminster area.21https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/foi-media/metropolitan-police/disclosure_2021/february_2021/correspondence-relating-to-protection-of-sir-churchill-s-statue-in-parliament-square2 The notes on some of the subjects of the “contentious statues” are often selective or slanted (this may, to be fair, be intended to reflect the reasons why they could be attacked by protestors rather than the force’s actual view).

Churchill’s entry on the Met list states, for instance, that he “referred to Indians as a ‘beastly people with a beastly religion’…his handling of the 1943-44 Bengal famine is particularly contentious, with Churchill having been accused of murdering over 3 million Indians.” The quotation is not in fact a documented direct quote but was said by a Cabinet contemporary, Leo Amery, to have been said to him by Churchill, in diaries published long after the former prime minister’s death. Most historians agree that an accusation of deliberate murder in Bengal cannot remotely be supported by Churchill’s actions and statements; he did order food to be dispatched and repeatedly expressed concern about the situation there, but wartime shortages of shipping and food restricted how much could be sent. |

Groups with no obvious interest in government policy or connection to the area appear to be allowed to treat it as a stage for their festivities and ceremonies

On 19 August 2021, a weekday, Whitehall was closed for thousands of Shia to march in commemoration of the festival of Ashura. There is no Shia place of worship or holy site in the vicinity. On the evening of November 28 2022, a hundred or so cars spent more than two hours, until after 10.30pm, driving in circles around Westminster to celebrate Albania’s national day, continuously hooting, playing loud music, revving their engines and causing traffic chaos, as the police looked on. No permission was sought for the latter event.

We recommend that festivities of this nature, except where they are of genuinely UK-wide national importance, should not take place around Parliament. There seems no reason why they should. Trafalgar Square (outside the proposed extension to the controlled area) or elsewhere are better places for these festivities, with more public space. The square, indeed, has a long history of such events. Where permission is sought for such events in Westminster, it should be refused and places such as Trafalgar Square offered as alternatives. Where it is not sought, vigorous enforcement should be applied.

There is significant disruption to travel affecting thousands and particularly the poorest

Parliament Square is a transport hub, used by around 40,000 motor vehicles a day22DfT traffic count estimates, https://roadtraffic.dft.gov.uk/#16/51.4995/-0.1274/basemap-countpoints and served by up to 128 buses an hour on ten routes which between them transported 43 million people in 2021/2.23https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports/buses-performance-data All these routes are regularly subject to hours, sometimes even days, of disruption by protests and events in the square and in Whitehall. Not all their passengers travel through the square, but the disruption would of course be felt all along the route.

Some of the worst-affected routes saw patronage fall by as much as 15 per cent between 2014, when there was little protestor disruption, and 2019, when there was substantial disruption, including the closure of Whitehall by eco-protestors for almost a week. There were also general declines in central London bus use in this period, but not by as much. Comparisons since 2019 are made difficult by changing working patterns after covid. The people affected by these disruptions are disproportionately the poorest workers, who use buses because they cannot afford the Tube.

Separately, some commuter coach services have stopped picking up in Westminster altogether because of “unpredictable traffic conditions caused by political related events.”24https://www.keybuses.com/article/what-future-commuter-coach

The public realm is poor and needs to be improved

Westminster is an extraordinary spectacle – the icon of Parliament, the broad, open square, the thirteenth-century Abbey, the grand Government buildings, and the river. But it is somehow no longer the sum of its parts.

Perhaps that is because you cannot appreciate the whole without making an effort. It is a choked and polluted traffic sluice, with most of its users – pedestrians – forced to the edges, to jostle with each other on narrow pavements. Just as the balance between protestors and everyone else is wrong here, so is the balance between people and traffic.

It is not always well cared for. As described, windows have remained broken and graffiti not fully cleaned for months, if not years. The small arcades under the buildings on Bridge Street are grubby and smelly, splotched with urine. As of November 2022, the grass in the middle of Parliament Square had been largely worn away, leaving a brown mudflat.

As long ago as 1947, the Architectural Review proposed pedestrianising the south side of the square.25https://www.thelondongardener.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Volume13_06_BarbaraSimms.pdf The Mayor, Sadiq Khan, promised during his 2016 election campaign to “revive plans to part-pedestrianise Parliament Square.”26https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/themes/569cb9526a21db3279000001/attachments/original/1457451016/x160668_Sadiq_Khan_Manifesto.pdf?1457451016

The car-borne terror attack on Parliament in 2017 gave new impetus to the idea and there is now a serious plan to remove general traffic from two sides of the square, the Parliament side and the St Margaret’s Church side, and send it two-way round the northern and western sides. The scheme is described by the Government as “similar to the conversion of Trafalgar Square from a large roundabout to the central pedestrianised area we see today, that connects the National Gallery on one side and a two-way working road system on the other.”27https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5160/documents/51000/default/

Abingdon Street, the road running south alongside the Palace of Westminster, would also be closed. The existing vehicle entrances to both the Commons and Lords would remain; access to them would still be allowed for those entitled to drive in, through security checkpoints moved further away from Parliament than now.

Physical barriers would prevent other traffic from driving on to the pedestrianised area. The scheme would create “security benefits for Parliament, particularly by pushing the perimeter of the estate further away from the palace,” according to Parliament’s director of security, Alison Giles.28https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8773/documents/88841/default

These plans are separate from another scheme, which is already being implemented, to install barrier gates in all the surrounding streets. Normally kept open, they can be closed if the area needs to be secured or a special event needs protection.

The pedestrianisation plans have been developed between the Speakers of both Houses, the GLA, TfL, the Abbey, the Supreme Court, Westminster Council and other local interests29ibid but have been drawn up rather quietly, with the only published details tucked away in the minutes of obscure parliamentary committees.

Parliament has agreed to fund concept designs, work on which began in March 2022 and was due to “take a year to complete with engagement across both Houses.”30https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9344/documents/160656/default/ But there is a row about who should pay for the actual works, estimated at a surprisingly high £80m.

“The intention is that the overall project costs would be shared between Westminster City Council, Transport for London and Parliament,” according to minutes of the Lords’ finance committee, but “Covid-19 has affected the financial position of the former two,” so they were refusing money.31https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8773/documents/88841/default The House of Commons finance committee “declined to recommend approval of the costs for the next phase until they received additional reassurances that Parliament, having covered the £3m for the [concept designs], would not be expected to pay the estimated £80m for the delivery phase in full.”32ibid

We recommend proceeding with the pedestrianisation scheme, which would greatly improve the experience of Westminster for visitors and those working there and would confer significant security benefits. Trafalgar Square has shown how it can be done. TfL, which now has a stable financial deal from the Government, and Westminster City Council should cover a share of the costs.

The owners of the area’s buildings and structures – nearly all of them official bodies – should immediately repair broken windows and properly remove graffiti. They should ensure that each building is inspected every day and that damage is immediately and fully rectified. Most of the streets are reasonably clean but whoever is responsible for the arcades under the buildings is falling down on their job.

| The “National Covid Memorial Wall” |

| The wall of St Thomas’s Hospital on the river walk opposite Parliament has been painted with more than 150,000 red hearts, stretching about a quarter of a mile, to commemorate the dead of covid. It is important, moving, aesthetically attractive, and has comforted many of the bereaved. The fact remains, however, that – as its creators admit – this substantial public space was appropriated without anyone’s permission.33https://news.sky.com/story/bereaved-families-paint-mural-of-almost-150-000-red-hearts-to-represent-covid-19-victims-12260412

Nor, despite its self-proclamation as a “national memorial,” was the nation or any national institution involved. The creators are two left-wing activist groups – Led by Donkeys, which specialises in billboards attacking Brexit and the Tories, and Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, which is stridently hostile towards the government’s performance during the pandemic. On the wall next to the hearts at the Westminster Bridge end are the prominent words, larger than almost any others, that the “gov[ernment] have failed.” These are, of course, views held by many people, but are not necessarily representative of all the victims commemorated – or of the nation. Two months after the memorial was unveiled, partly due to the success of the covid vaccine programme, the Tories won the 2021 local elections with an 8 per cent swing. It is seldom right to mix political slogans and monuments to the dead. And however righteous this cause, it establishes a precedent for the seizure of public space which could be used by others. Might, for instance, a far-right group apply the same logic to put a politically-charged “national memorial” in Westminster to the victims of Islamist terror? We recommend that there should be a prominent national memorial in central London to the victims of covid – maybe even this one, on this site, though shorn of political slogans. But the decision on where it is and what it says should be for a nationally representative body, not partisan and self-appointed campaign groups. |

Next chapter

How we got here: recent legislation protecting access to Parliament

Until 2005: sessional orders that didn’t quite work

From 1842 to 2005, the main instrument controlling gatherings round Parliament was the Sessional Order passed at the beginning of each session, directing that the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police “do take care that during the Session of Parliament the passages through the streets leading to this House be kept free and open and that no obstruction be permitted to hinder the passage of Members to and from this House.”34https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmproced/855/3070202.htm

The consequent directions made by the Commissioner covered an area far wider than anything more recent: “East side of the River Thames between Waterloo and Vauxhall Bridges, Vauxhall Bridge Road, Victoria Street (between Vauxhall Bridge Road and Buckingham Palace Road), Grosvenor Gardens, Grosvenor Place, Piccadilly, Coventry Street, New Coventry Street, Leicester Square (north side), Cranbourn Street, Long Acre, Bow Street, Wellington Street, crossing Strand and Victoria Embankment to Waterloo Bridge.”35ibid

The Lords still passes this order each session.36https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2022-05-10/debates/68A747E0-7E5B-44D3-9D54-969B82AE09AD/StoppagesInTheStreets But the Commons gave up after learning that the order and the directions do not, in fact, confer any special powers of enforcement. In 2003, after Churchill’s statue had been defaced by anti-capitalist marchers, the Iraq war had begun the more protest-ridden modern era, and the demonstrator Brian Haw had set up camp in Parliament Square, the Commons’ procedure committee looked at the issue.

It heard that any arrest would have to be under other, general powers, such as for wilfully obstructing a police officer in the execution of his duty, for breach of the peace, or for public order offences.37https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmproced/855/85507.htm The then Clerk of the Commons, Roger Sands, said that the Sessional Order might make MPs “feel better”38https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmproced/855/3070206.htm but gave them the “mistaken belief that its effect is to confer special and additional legal authority on the police in relation to the precincts of Parliament.”39https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmproced/855/3070202.htm In practice, “new legislation would be needed to change the situation [on protests] to a significant degree.”40ibid

2005-2011: a controlled area is created

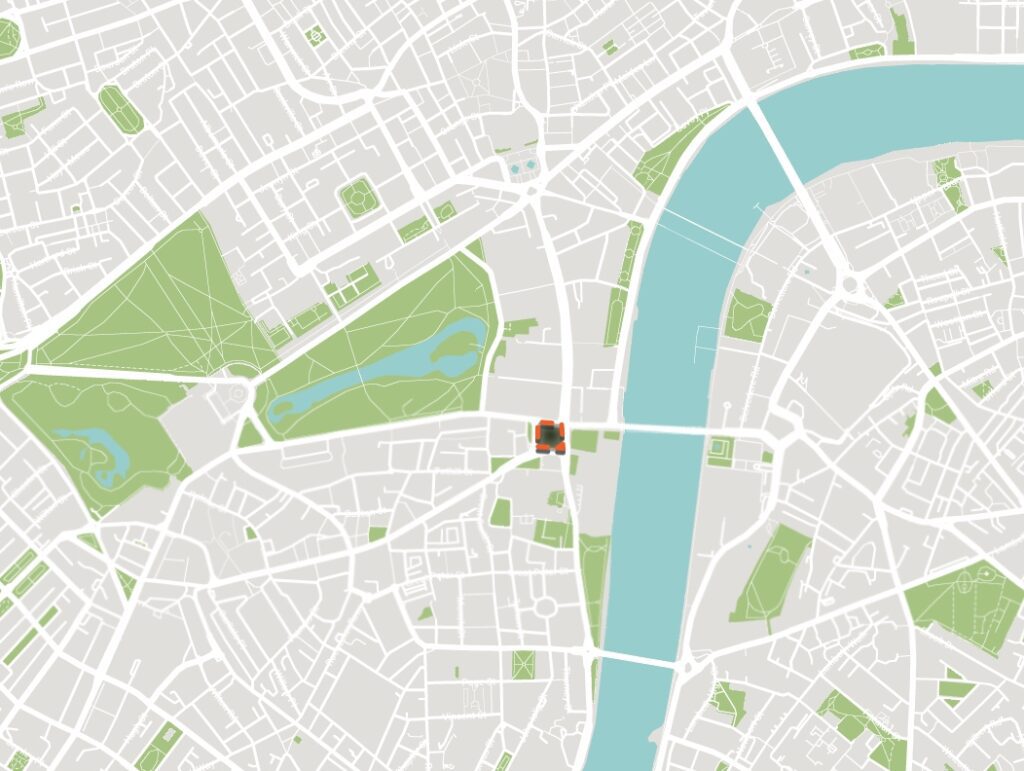

Controlled area between 2005-2011

The new legislation duly arrived. Under sections 132-8 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 200541https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/15/section/132/enacted, the Home Secretary could specify a “designated area” of up to a 1 kilometre radius from Parliament Square. The area42https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2005/1537/article/2/made wasn’t in practice a perfect 1km circle (see map above) but covered almost all the government departments.

Inside it, loudspeakers were banned at all times. Demonstrations had to be notified to the police at least 24 hours before. Crucially, under section 134(2) police were obliged to allow them if this notice was given – but could impose conditions on duration, size, location, banners, and noise. Demonstrators were not allowed to obstruct access to Parliament.

During this period, significant progress was made on clearing Parliament Square of the wider protestor campsite that had set up there. A 2010 High Court ruling, citing the 2005 act, led to the eviction of the so-called “Democracy Village” which took up 70% of the green space in the square.43https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2010/1613.html, para 33

But the law – often wrongly described as a “ban” on protests – became a cause celebre for a wide spectrum of groups including the opposition Conservative Party, then in its hug-a-hoodie phase. David Davis, the shadow home secretary, branded it a “contempt of democracy and a contempt of people’s right to protest.”44Financial Times, 16.6.05. A Daily Telegraph leader called it “grossly disproportionate.”45Telegraph, 24.5.06.

One 25-year-old, Maya Evans, was given a conditional discharge for standing at the Cenotaph and reading out the names of the war dead – though Bow Street magistrates were told she would have been given permission had she asked.46Evening Standard, 8.12.05. The artist Mark Wallinger won the 2007 Turner Prize for recreating Brian Haw’s peace camp at Tate Britain, claiming a line he’d drawn on the gallery floor showed how the restricted zone “bisects the Tate and the work itself.”47Telegraph, 16.1.07.

Tate PRs panted that they’d had to consult lawyers lest the work was itself illegal. Art critics swooned that Mr Wallinger had made “protestors – and lawbreakers – of us all.”48Observer, 21.1.07. Alas, the actual restricted zone49https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2005/1537/article/2/made came no closer to the Tate than Thorney Street, separated by 150 metres and the Millbank Tower from Mr Wallinger’s line on the floor – and didn’t apply indoors anyway.

It was usually also overlooked that Mr Haw – having failed in his legal claim that the 2005 act didn’t apply to him – was in fact not banned under it, but was given permission to continue his demonstration and camp in Parliament Square.50Telegraph, 26.5.06, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-13828800 (He was banned from displaying large numbers of banners, and there was criticism of a “heavy-handed” police operation to confiscate these.)

In 2006, figures on the supposed ban were given in an answer to the London Assembly. In the first fourteen months, police said, 1163 applications for protests within the restricted area were made of which 1158 were approved and five, presumably including Brian Haw’s, had conditions placed on them.51https://www.london.gov.uk/questions/2006/0350-0

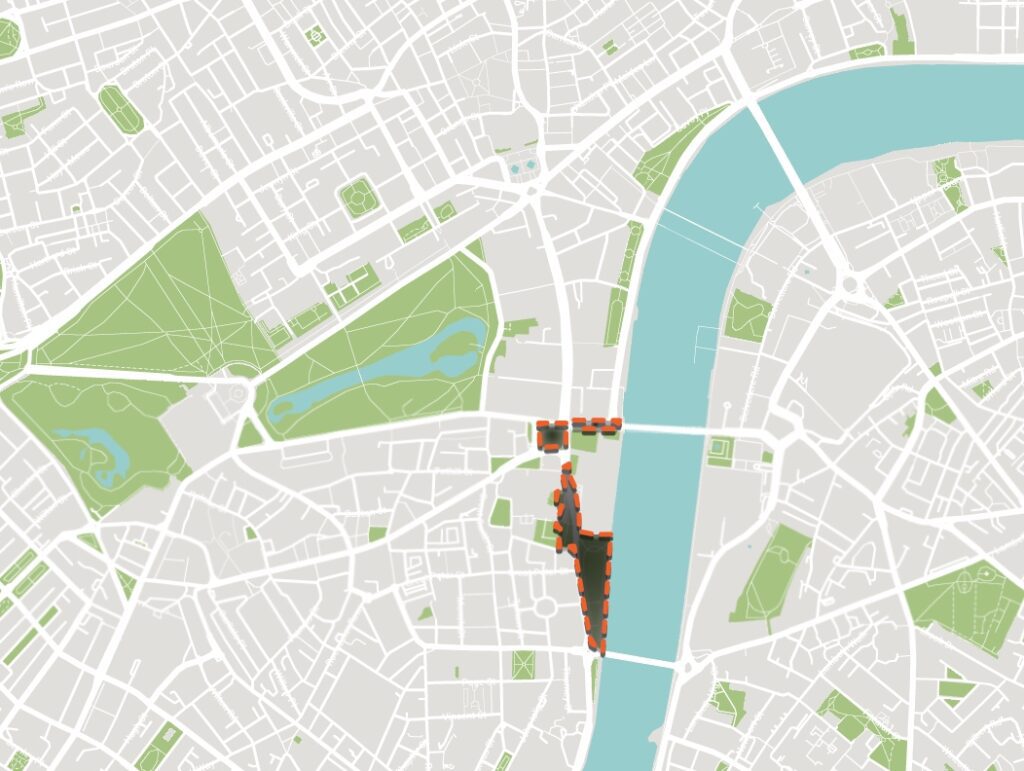

2011-2014: the controlled area is almost totally abandoned

Controlled area between 2011-2014

In 2011, the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act repealed sections 132-8 and created a much smaller controlled area, only the green space and pavements in the middle of Parliament Square (see map above). The 2005 restrictions had been so successfully delegitimised that even the David Cameron government appeared to accept the claim that they had banned demonstrations. As the Home Office put it in its briefing on the new Act: “The Government is committed to restoring rights to non-violent protest.”52https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/98383/fact-sheet-parliament-square.pdf

But the Act did remove the presumption that demonstrations had to be approved if permission was sought in time, and added new provisions directly banning camping and structures on the square. Brian Haw’s peace camp lost steam after he died in 2011, though it continued for a while under sympathisers. By 2013, after 12 years, it was gone, the fences protecting the green space from future protest camps came down and the public was able to picnic on the grass.53https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/peace-at-last-final-antiwar-protesters-leave-parliament-square-after-12-years-8608893.html

Even as the 2011 act went through parliament, some – including the Home Office’s briefing document – were asking if the controlled area was now too small.54https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/98383/fact-sheet-parliament-square.pdf Massive, sometimes violent, demonstrations against austerity and tuition fees by students and others sealed off Parliament for hours on end. This was the time when one young man, Charlie Gilmour, swung from the flag of the Cenotaph. By 2013, peers were complaining that noisy demonstrations at their end of the building, outside the controlled area, made work “almost impossible” and demanding an extension of the restricted area as “the only thing between us and our sanity.”55https://www.theyworkforyou.com/lords/?id=2013-11-25a.1208.2

2014-22: the controlled area is enlarged, first a bit and then some more

Controlled area between 2014-2022

Controlled area currently

The Antisocial Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 amended the 2011 act, extending the controlled area to Bridge Street, St Margaret Street, Old Palace Yard, Abingdon Street, Abingdon Street Garden (also known as College Green, often used for media interviews), and the Victoria Tower Gardens.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 further extended the controlled area to Parliament Street, Canon Row, Derby Gate, all of Parliament Square and the Victoria Embankment as far as Richmond Terrace, just south of the Ministry of Defence.

But it is still much smaller than in 2005, and most of the government district remains outside the controlled area

The controlled area now covers the roads outside the main parliamentary buildings, most of the outbuildings, and New Scotland Yard. However, large parts of the government district – including the whole of Whitehall, the entrance to Downing Street, and almost all departments – remain outside it. That is one of the reasons why protestors still play loud music late at night to keep the PM awake, for instance, block the pavements, or erect shacks on the pavement opposite Downing Street – though other legislation could still be used against them with sufficient will, see below. The 2022 Act allows the Home Secretary to extend the controlled area, but only to roads outside buildings where Parliament may move as a result of the (now stalled) refurbishment project.

We recommend that the “controlled area” for protests be restored to what it was until 2011, namely up to within one kilometre of Parliament, covering all the main departments, Whitehall, Downing Street, King Charles Street, Horse Guards Road and Marsham Street. The actual operation of the 2005 act – as opposed to the false picture of a “protest ban” which was created around it – successfully balanced the right to protest with the rights of others to go about their work and lives.

Even where the controlled area does not apply, existing public order and highways legislation offers several avenues which could be more fully exploited, particularly with new legislative moves now in Parliament

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 gave the police new nationwide powers to restrict public processions and public assemblies which could cause “serious disruption to the life of the community” or cause noise sufficient to cause “serious disruption to the activities of an organisation which are carried on in the vicinity.” So far, these powers do not seem to have been used against disruptive protest outside the controlled area.

Under the Highways Act 1980, obstructing the highway without lawful authority or excuse is a criminal offence. However, the Supreme Court has ruled (the so-called Ziegler judgment) that protestors should not be convicted if obstructing the highway was a disproportionate interference with their European Convention rights of assembly and free expression. The judgment has spilled over into offences other than obstruction, including criminal damage. It has caused the police more difficulties and made them more cautious in making arrests, often meaning that they wait to act until it is clear that a protest is causing “significant obstruction.” College of Policing (CoP) guidance to officers imposes further layers of hesitancy on the police response.

Policy Exchange described the problem in our report The ‘Just Stop Oil’ protests: a legal and policing quagmire, October 2022,56https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-%E2%80%98Just-Stop-Oil-protests.pdf arguing that the CoP guidance should be overhauled and that Parliament should legislate to reverse Ziegler. Amendments to do the latter have been tabled to the Public Order Bill currently in Parliament. See our recent paper Amending the Public Order Bill (January 2023) for further detail.57https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Amending-the-Public-Order-Bill.pdf

We recommend that until the controlled area can be extended, existing public order and highways legislation should be used to its fullest extent; that College of Policing guidance on Ziegler should be overhauled; and that Parliament legislate to reverse the Ziegler judgment.

Enforcement has long been poor, and still remains hesitant

Concern about disorder round Parliament perhaps peaked with the harassment of the then Tory MP Anna Soubry by a mob in early 2019, in the controlled area, as police officers stood by. The columnist Owen Jones was also targeted in the same period. Other notable crowd incidents include when the BBC journalist Nick Watt and the levelling-up secretary, Michael Gove, were chased by mobs in June and October 2021 respectively. Those incidents took place in areas which were part of the original 2005 controlled area, but were removed from it by the 2011 Act.

The Soubry incident, which was filmed, sparked a full-scale inquiry by Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights. This concluded that “those responsible for policing and controlling [the area round Parliament] have not always given the need for access without impediment or harassment the importance it requires… While some MPs find the police concerned and helpful, others report the police showing more sympathy with the assailant rather than the MP victim.”58https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf

The SNP MP Joanna Cherry KC told the committee: “Police officers have been present [while I was being harassed] and, in my experience, done nothing. I do not think it is legitimate for someone to walk alongside an MP screeching ‘Traitor’ or something more abusive at them… I know from personal experience MPs who have refused to go out because they have been afraid of abuse or indeed physical violence.”59http://data.parliament.uk/WrittenEvidence/CommitteeEvidence.svc/EvidenceDocument/Human%20Rights%20(Joint%20Committee)/Democracy,%20free%20speech%20and%20freedom%20of%20association/Oral/101203.html

In evidence to the committee, the then Metropolitan Police commissioner, Dame Cressida Dick, said that the force’s “posture generally at the time [of the Soubry incident]… was too passive overall. Since then, you will have seen a very big step-up in the resourcing of the policing of the protests around Parliament… We believe that we are now much more present and more active, and the officers are, if you like, more interventionist.”60http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/human-rights-committee/democracy-free-speech-and-freedom-of-association/oral/101929.html

The Joint Committee on Human Rights pointed out: “No matter how strict a legal regime is, it will be ineffective if not enforced.”61https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf But the crime statistics shown above suggest that insufficient progress has been made, with only modest reductions (even in the pandemic years) in public order offences since the big spike in 2018/19.

It is possible that some of the sustained nature of the increase is related to more intense enforcement. However, police do not seem to be consistently using their new powers. The traffic island in Parliament Street occupied by Steve Bray is within the extension to the controlled area under the 2022 act, in force since June. Amplifiers and loudspeakers are now explicitly banned in this area without permission. The law also allows police to make a simple oral direction that Mr Bray, or anyone else carrying on a banned activity, stop it and not resume for up to 90 days.62https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/13/section/144 But as of November 2022, Mr Bray is still being allowed to regularly play loud amplified music on loop there for hours on end.63https://twitter.com/MrHarryCole/status/1592898425175306240

Occasionally, officers confiscate his equipment. The law explicitly allows them to “seize and retain” it for up to 28 days, or until court proceedings are finished, or permanently on conviction for breaking the ban64https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/13/section/145 – but according to Mr Bray, it is instead swiftly and painlessly returned for him to start the performance again. Even he appears surprised by this. On November 3, after a performance the previous week, he tweeted: “Strange but true: I went to Charring (sic) Cross Police station to collect my amp on Tuesday. “I’ve come to collect my speaker, do you want the reference number?” “Your what?” “My Amplifier” “Oh you’re Steve Bray” Less than 1 min later Amplifier returned, no signing, paperwork etc.”65https://twitter.com/snb19692/status/1588317225056096257

The law (section 147 of the 2011 act, as amended) allows demonstrations or amplified protests in the controlled area with permission. To balance the rights of protestors with the rights of others, we recommend that there be a presumption (as in the 2005 legislation) that protestors must be given permission, if they apply, but that conditions should be applied. These should typically require protests to be shorter.

We endorse the Joint Committee’s recommendation that there should be zero tolerance for obstruction and intimidation around the Palace of Westminster. A dedicated team of police officers should patrol the area on foot, bicycle and by motor vehicle to achieve this, maintain public order, reduce harassment and intercept and pre-empt unauthorised demonstrations before they can take hold. For protests in breach of the conditions, the law should be consistently and firmly enforced. Directions to protestors should be given. Where these are breached, equipment should be confiscated and prosecutions brought.

Ownership and lines of responsibility are deeply confused

As the Joint Committee report put it, “the fragmentation of responsibility is particularly noticeable when it comes to policing the Palace of Westminster and the area around Parliament.”66https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf In total, the public spaces near Parliament are controlled by at least eight different bodies – Parliament itself, Westminster council, TfL, the GLA, Lambeth council, the Royal Parks, the Government and the Church. The government publishes an 11-page guidance document and five-colour map showing who has which bits.67https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/364469/Parliament_Square_Guidance.pdf Symbolising the confusion around the subject, it is now wrong, not having been updated with the 2022 extensions to the controlled area.

Tiny sub-areas are a patchwork quilt, with Parliament Square alone split between three bodies. The Greater London Authority – in effect, the Mayor of London – controls the grass in the middle of the square, and licences protests and events on it. Westminster City Council controls the pavement immediately around the grass, the roadway, and the pavement on the other side. The Royal Parks controls the grass area in front of the Supreme Court.

Just down the road, half of Old Palace Yard is controlled by the council and the other half is controlled by the Government; the Home Secretary is the responsible minister. College Green, immediately to the south, is controlled by the House of Commons. On Westminster Bridge, the road belongs to TfL. Half the pavement is the responsibility of Westminster council and half of it Lambeth. Of the 35-odd street statues in the area (frequent targets of attack by protestors), about half are cared for by Westminster council, 40 per cent by English Heritage, 5 per cent by Parliament and 5 per cent by others. Policies on cleaning them up appear to differ between custodians.

Protestors have often been able to exploit the different jurisdictions – and policies – of the different bodies. When the courts evicted Brian Haw from the (GLA-controlled) grass in Parliament Square, he simply moved a few feet to the (Westminster Council-controlled) pavement next to it.

The GLA and Westminster City Council can also licence protests or events in their parts of the estate. The police are still the ultimate authority and can overrule them. However, they feel constrained in setting conditions in the GLA-owned part. Both national legislation and the GLA’s own bylaws68https://www.london.gov.uk/media/1062/download prohibit loudspeakers, but in evidence to the Joint Committee on Human Rights, the Met’s then commander of major operations, Jane Connors, explained that the loudspeaker ban was not enforced on the Parliament Square grass because it was “under the GLA… [and] depending on the protest they will allow some activity in relation to that. For us to be able to enforce [the ban] the landowner needs to say that they are not going to have it.”69http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/human-rights-committee/democracy-free-speech-and-freedom-of-association/oral/101929.html

As the committee noted, “we asked the GLA about [its] approach to policing around Parliament… We were surprised that while the GLA takes freedom of expression and freedom of assembly into account in deciding what to allow, its response made no reference to the needs of Parliament or a functioning democracy.” The committee was further surprised to learn that the GLA did not consult with the Parliamentary Security Department in deciding what protests to allow.70https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201919/jtselect/jtrights/37/37.pdf It said there was “a case for considering… legislative change in control of the area round the precincts.”71ibid

We recommend that control of the centre of Parliament Square, grass and pavements, is removed from the GLA and Westminster City Council and returned to the Government. We recommend the same for the Royal Parks-controlled part of Parliament Square and the whole of Old Palace Yard. Westminster Council should continue to control the streets and pavements elswehere but its role and that of the GLA in respect of applications for protests should end.

We recommend that the rules should be made clear (to protestors, workers in the area and all those charged with enforcement) by being laid down in simple terms on a website and on noticeboards in the area.

The Government has been relatively non-committal on most of these issues

The Government took 18 months to respond to the Joint Committee on Human Rights’ report. It said it had “worked closely with [the police]… to identify where the police need more powers to deal with protests which are peaceful but cause significant disruption. We have considered what can be done to make a real difference in the policing of such protests.” It pointed towards the extended powers in the 2022 act but did not commit to any further Westminster-specific powers, or to supporting the public realm proposals for Parliament Square.