Authors

Content

-

- The immediate parliamentary reaction to the ICJ’s advisory opinion

- The Government’s statement on the ICJ’s advisory opinion

- Sovereignty and justice for the Chagossians

- The Government’s November 2022 statement about negotiations on the exercise of sovereignty

- The debate about the UK’s sovereignty over the Chagos Islands

- Conclusions

Foreword

Admiral the Lord West of Spithead GCB DSC PC

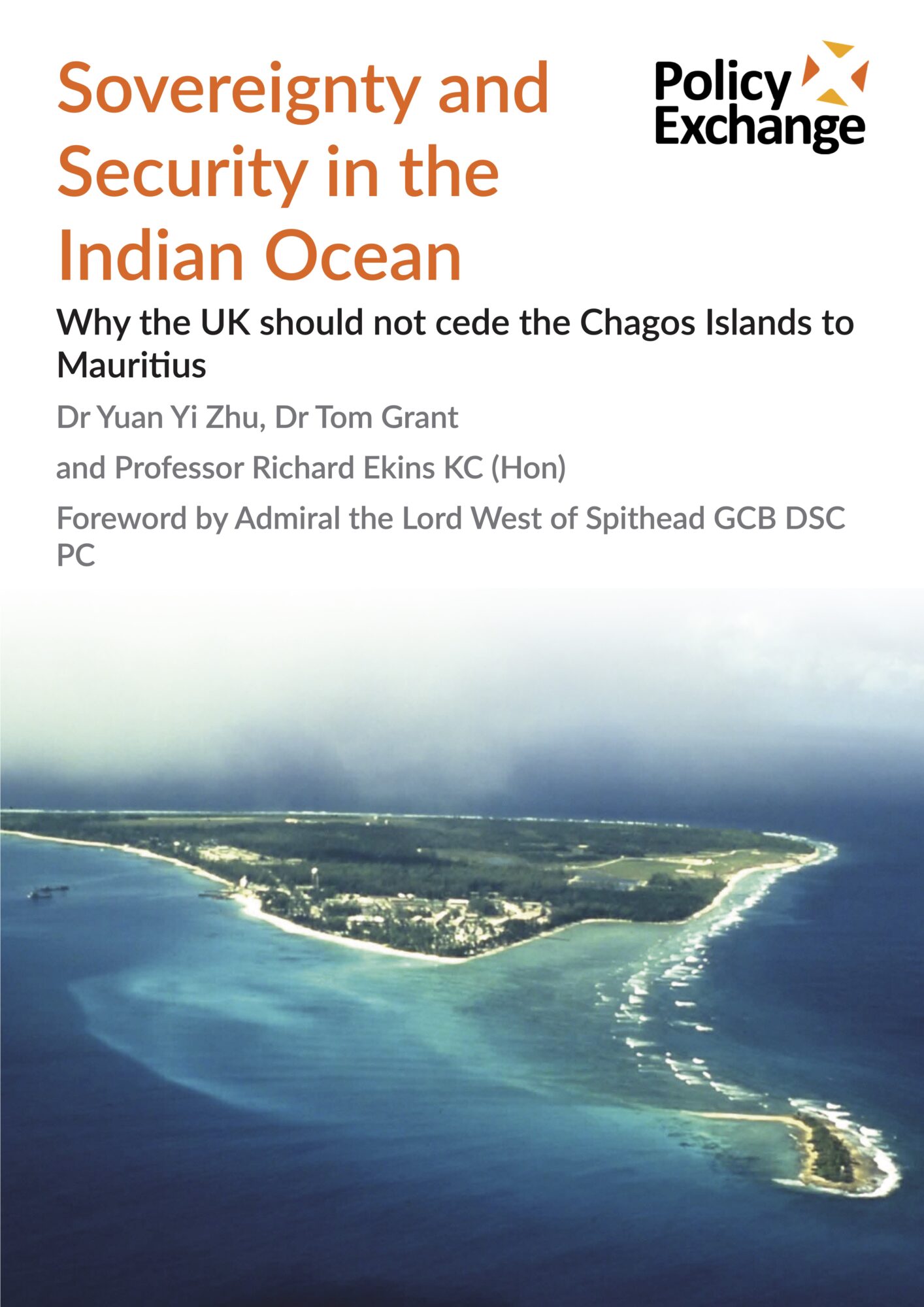

When looking at strategic options for military action in the Indian Ocean – and unimpeded access by sea and air to the bordering countries of the Indian Ocean, from South Africa past Somalia, Yemen, Iran, the Arabian Gulf, Indian sub-continent, Indonesia and Australasia – Diego Garcia is a strategic jewel, possession of which is crucial for security in the region and hence our national security. It allows coverage of the choke points south of the Cape of Good Hope, the Bab-el-Mandeb, Straits of Hormuz and Malacca Straits through which a huge quantity of global trade passes. It is no exaggeration to say that Diego Garcia – the largest of the Chagos Islands – hosts the most strategically important US air and logistics base in the Indian Ocean and is vital to the defence of the UK and our allies.

Having visited Diego Garcia twice and utilised it in op-plans and routine deployments of carriers and SSNs, I was delighted to read this paper by Policy Exchange which calls on the Government to cease negotiations with Mauritius about cession of the Chagos Islands.

The paper makes out an irrefutable case that ceding the Chagos Islands to Mauritius would be an irresponsible act, which would put our strategic interests – and the interests of our closest allies – in danger, while also recklessly undermining fundamental principles of international law.

It would drive a coach and horses through the vision set out in the Integrated Review in 2021 (Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 2021).

How on earth can the Government explain a decision to negotiate with Chinese-aligned Mauritius to hand over sovereignty of the strategically vital island of Diego Garcia, an island which is located some 2152 kilometres from Mauritius itself. It would be a colossal mistake and one which opposition parties in Parliament would also be complicit in, given they are supporting the Government’s stance.

There can be little doubt that the Chinese are pushing Mauritius to claim Diego Garcia and that China wants access to and control of the port and airfield facilities. The depth of the Sino-Mauritius relationship is evident in the 47 official Chinese development finance projects on the island.

The Integrated Review Refresh 2023 was sub-titled “Responding to a more contested and volatile world”. Is this how the Government wishes to respond? An agreement with Mauritius to surrender sovereignty over the Chagos Islands threatens to undermine core British security interests, and those of key allies, most notably the United States. By agreeing the very principle of a Mauritian claim over Diego Garcia they are also putting at risk other British Overseas Territories such as the Falkland Islands.

As the paper explains, the claim by Mauritius to sovereignty over the Chagos Islands is dubious at best. The report begins by reviewing the historical record, which reveals the artificial nature of the claim that Mauritius is now making. The link between Mauritius and the Chagos Islands amounts to little more than an accident of colonial history. Thousands of kilometres apart, the Chagos Archipelago was simply attached to the British colony of Mauritius for administrative convenience. If there is any legitimate grievance it is on the part of the descendants of those who were living on Diego Garcia at the time the joint UK/US air base was established between 1968 and 1973 and who were forcibly expelled.

The historical record makes clear that the Mauritian claim to the Chagos Islands is scarcely a campaign for justice for the Chagossians. The Chagossians have not been consulted in advance of these negotiations and indeed have been excluded from them. They have been cynically weaponised by Mauritius in order to press its territorial claims. Mauritian officials have even claimed that Chagossians who seek to be represented in the negotiations are no more than British pawns, merely for wanting to have their voices heard over the future of the Islands. Ceding the Chagos Islands to Mauritius will not address the plight of the Chagossians, who Mauritius has consistently ignored. Indeed, Mauritian treatment of the Chagossians has led many thousands of them to settle in the UK.

Should these negotiations proceed and result in effectively allowing the Chinese military to prevail we will have perpetuated the Chagossians’ long and unhappy impasse and needlessly put ourselves, our allies and the region at risk.

I strongly support the recommendations of the paper.

Next chapterExecutive summary

On 3 November 2022, in the course of the short-lived Liz Truss premiership, the Foreign Secretary announced that the UK was entering into negotiations with Mauritius about the exercise of sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), one of the United Kingdom’s fourteen overseas territories. Whatever terms the UK may agree with Mauritius, cession of the BIOT would be a major, self-inflicted blow to the UK’s security and strategic interests, which seems to be premised on the Government’s misunderstanding of the UK’s international legal position. In fact, the UK is under no moral or legal obligation to cede the BIOT to Mauritius.

The BIOT is situated in the middle of the Indian Ocean and is made up of more than a thousand islands in the Chagos Archipelago, most of which are very small. The largest island, Diego Garcia, is the site of a US/UK joint military facility, which is vital to the defence of the UK and our allies. The strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific region is only increasing. With the return of great power competition, and an increasingly aggressive Chinese regime active throughout the region, the BIOT is of fundamental importance to UK security and foreign policy.

Successive British governments have consistently maintained that UK sovereignty over the Chagos Islands, which dates from 1814, was beyond question. The Government’s announcement of its decision to enter into negotiations with Mauritius refers to “relevant legal proceedings”, which must mean an advisory, non-binding opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2019 and a decision of a Special Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS Special Chamber) in 2021, in a dispute between Mauritius and the Maldives.

In 2017, the United Nations General Assembly requested an advisory opinion on the initiative of Mauritius and over the objection of the UK, United States, Australia, and others.1GA res. 71/292, 22 June 2017. The proceedings concluded in 2019 with an advisory opinion in which the ICJ said that the decolonization of Mauritius had not been completed in 1968, notwithstanding the accession of Mauritius to independence that year, and that the UK is under an international legal obligation to terminate its administration of the BIOT.2Legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965, Advisory Opinion, 25 Feb. 2019, ICJ Rep. 2019, p. 95 at 140 (para. 183).

In 2021, in a dispute concerning maritime boundary delimitation in the Indian Ocean, the ITLOS Special Chamber adopted a judgment rejecting preliminary objections that the Maldives had advanced against its exercise of jurisdiction over the matter. This included the objection that the sovereignty dispute in respect of the Chagos prevents the adjudication of a maritime boundary between the Chagos and the Maldives. According to the ITLOS Special Chamber:

Mauritius’ sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago can be inferred from the ICJ’s determinations [set out in the 2019 Advisory Opinion].3Dispute concerning delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius/Maldives), ITLOS Case No. 28, Preliminary Objections, Judgment, 28 Jan. 2021, para. 246.

The Maldives, in October 2022, suggested that it now supports General Assembly action recognizing the Chagos to form part of the territory of Mauritius.4“Attorney General defences stand to recognise Chagos as part of Mauritius”, The Times of Addu, 23 October 2022, https://timesofaddu.com/2022/10/23/ag-defends-stand-to-recognize-chagos-as-part-of-mauritius/ This reflects a shift from the Maldives’ earlier position.5Philip Loft, British Indian Ocean Territory: UK to negotiate sovereignty 2022/23 (Research Briefing No. 9673, 22 Nov. 2022), https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9673/CBP-9673.pdf at p. 22, sec. 5.1.

Up until 3 November 2022, the Government consistently maintained that the ICJ’s advisory opinion had no legal force and did not require, or warrant, a change in the UK’s long-standing position that it enjoyed sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. The Foreign Secretary’s November announcement does not formally abandon this position, but may do so in effect. The same is true for subsequent ministerial statements in the House of Commons, including in answering parliamentary questions about the progress of the negotiations. There are thus strong reasons to fear that the Government is acting under the misapprehension that the 2019 ICJ advisory opinion and the 2021 ITLOS decision between Mauritius and the Maldives require a change in the UK’s legal position.

The aim of this report is to contest this misapprehension. We show that many parliamentarians have misunderstood the legal significance of the 2019 ICJ advisory opinion, the legal significance of which is plainly misrepresented in the 2021 decision of the ITLOS Special Chamber. The Government’s initial response to the advisory opinion was entirely correct. The ICJ’s advisory opinion does not and cannot place the UK under an obligation to cede the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. Neither does the opinion empower the General Assembly to determine the matter. Putting the point at its lowest, even if one overstated the legal significance of the advisory opinion, which would be a mistake, it would nonetheless still be open to the UK to consider options other than cession to Mauritius, including arranging some form of free association of the Chagos Islands with the UK.

Further, it would be a mistake for the Government to think that the UK’s legal position is likely to worsen, such that it should negotiate now to cede the BIOT on favourable terms, which might help assure the future of the joint military facility at Diego Garcia. As this report argues, the principle of state consent is fundamental to international law. Without UK consent, no tribunal, no court, including the ICJ, can exercise jurisdiction over the UK to require – to order – cession of the BIOT to Mauritius. The UK is entirely free to stand its legal ground, as previous governments have done. It is possible, of course, that a future British government might cede the BIOT to Mauritius without assurances (which in any case are of very little value) in relation to Diego Garcia, especially if such a government took the view that the international rule of law required immediate and unconditional cession. For all the reasons set out in this paper, this would be a gross failure of statesmanship. However, the risk that a future government might act irresponsibly is no reason for the present government to abandon the UK’s legal rights and thus compromise our national security and the strategic interests of our allies.

This report begins by reviewing the historical record, which reveals the artificial nature of the claim that Mauritius is now making. The link between Mauritius and the Chagos Islands amounts to little more than an accident of colonial history. Mauritius agreed to sell the Islands and to renounce its rights over them for £3m in 1965 and Mauritius’ first post-independence leader, who negotiated both his country’s independence and the cession of the Chagos Islands to the UK, described the islands as “a portion of our territory of which very few people knew… which is very far from here, and which we had never visited”. It was only in 1982, many years after independence, that Mauritius decided to claim sovereignty over the Islands. It has waged an effective political campaign through various international institutions, including the General Assembly, with the ICJ advisory opinion one important milestone in this campaign. The UK should not yield to this form of pressure, especially not when buckling under pressure would also put our vital strategic interests in danger.

The historical record also makes clear that the Mauritian claim to the Chagos Islands is scarcely a campaign for justice for the Chagossians. Many parliamentarians are rightly concerned about their plight, with legislation enacted in 2022 to extend British citizenship to them. The Chagossians have not been consulted in advance of these negotiations and indeed have been excluded from them. In effect, their expulsion from the Chagos Islands by British authorities (with Mauritian consent) – for which they have received compensation several times, and now British citizenship – has been cynically weaponised by Mauritius in order to press its territorial claims. Mauritian officials have even claimed that Chagossians who seek to be represented in the negotiations are no more than British pawns, merely for wanting to have their voices heard over the future of the Islands.

Ceding the Chagos Islands to Mauritius will not address the plight of the Chagossians, whose interests and voice Mauritius has consistently ignored and whose treatment of the Chagossians has led to many thousands of them to settle in the UK. Cession would, however, put the strategic position of the United Kingdom and its allies in the Indo-Pacific region in jeopardy, paving the way for China to fill the strategic void. If the UK does not enjoy sovereignty over the BIOT, the joint military facility is at risk. Whatever assurances Mauritius may give in relation to the future of the base at Diego Garcia, there is absolutely no guarantee that a future Mauritian government, under Chinese economic and political pressure, will not resile from these assurances or allow a Chinese military or intelligence presence on other islands in the archipelago, which would constitute a serious threat to our security interests.

For the Government to accept, even implicitly, that the ICJ’s advisory opinion was binding will undermine the principle of state consent, which underpins international law. The consequences of the Government’s apparent position do not end here. Accepting the maximalist Mauritian case threatens to encourage territorial irredentism around the world, and may even put into jeopardy the statehood of post-colonial sovereign states which were created as the result of the split of larger colonial territories.

Ceding BIOT will also threaten the UK’s sovereignty over other overseas territories, notably the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus, the last of which were also detached from a then-colony for defence purposes. Argentinian officials have already repeatedly used the UK’s willingness to negotiate with Mauritius on the basis of the ICJ advisory opinion to push for negotiations over the sovereignty of the Falklands.

The Government should revert to the longstanding, cross-party position that the UK enjoys sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. It should explicitly reject the assertion that the ICJ’s advisory opinion was legally binding and should make clear that the Chagos Islands will not be ceded to Mauritius. Other parliamentarians, from all parties and none, should make clear that they oppose cession and should refuse to ratify any treaty of cession. In particular, the Opposition should abandon its apparent (confused) policy of support for cession and, in company with past Labour governments, defend UK sovereignty over the BIOT. The Government should recognise that ceding the Chagos Islands, especially on mistaken legal premises, would be an irresponsible act, which would put our strategic interests – and the interests of our closest allies – in danger, while also recklessly undermining fundamental principles of international law.

Next chapterRecommendations

The central argument of this report is simple. International law does not require the UK to cede the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. For the Government to misunderstand the ICJ’s advisory opinion to require cession would be a serious mistake which would harm the UK’s strategic interests, not only in the Indian Ocean but in relation to its other overseas territories and military installations abroad. For the Government to act on the basis of a fear that the UK’s legal position will somehow worsen in the future, such that the choice is between cession with conditions now or unconditional cession later, would be wholly irrational. As long as the British government refuses to give its consent to the dispute between it and Mauritius to be heard by an international court—which it has every right to do under international law—its sovereignty over the Chagos islands cannot be threatened.

This argument supports the following recommendations.

- The Government should not cede the Chagos Island to Mauritius and should discontinue negotiations to the extent that their aim is to conclude a treaty of cession.

- The Government should maintain British sovereignty over the entirety of the BIOT for as long as they are required for defence purposes. It should not relinquish sovereignty over the islands in return for an unenforceable promise by a third country that the military base at Diego Garcia will be allowed to continue to operate in the future.

- The Government should make a statement in the House of Commons affirming the long-standing position that the UK enjoys sovereignty over the BIOT and that the Government does not accept that the ICJ’s advisory opinion, or resolutions of the General Assembly, requires the UK to cede the Islands to Mauritius.

- The Government should make clear that under no circumstances will it cede the Chagos Islands to Mauritius without first consulting the Chagossians, which may include making provision for continuing free association with the UK.

- The Government should consult with the Chagossians about the possibility of facilitating returns to the Chagos Islands, provided that this does not constitute a risk to the UK-US joint facility at Diego Garcia.

- Parliamentarians of all parties and none, in both Houses of Parliament, should ask the Government why it has abandoned the UK’s long-standing position in relation to the Chagos Islands and should remind the Government that the ICJ’s advisory opinion cannot impose a legal duty on the UK to cede the Islands to Mauritius.

- Parliamentarians should put pressure on the Government to make the commitments noted above and, in accordance with the statement made by the minister on 7 December 2022, to undertake not to attempt to evade section 20 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (say by use of the Colonial Boundaries Act 1895 or some other means). That is, the Government should lay a treaty of cession before the Houses of Parliament, which should have the opportunity to consider and reject it.

- Parliamentarians should also make clear to the Government that they will resolve not to ratify a treaty of cession that is laid before Parliament.

- The Opposition should clarify (and should be asked by journalists and other parliamentarians to clarify) whether a future Labour government would treat the ICJ’s advisory opinion, with or without the subsequent ITLOS preliminary ruling and General Assembly resolution, as imposing a legal obligation on the UK to cede the BIOT to Mauritius.

- The Opposition should return to the UK’s and successive Labour governments’ long-standing position in relation to these matters and should demand that the Government do likewise, making clear that cession of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius would not enjoy cross-party support.

Chronology

- Antiquity: the existence of Chagos attested to in the Maldivian oral tradition.

- c. 1512: first European mention of the Chagos on a map.

- 1774: France claims Peros Banhos, the first territorial claim in the Chagos Islands.

- c. 1783: first permanent settlement by the French in the Chagos Islands.

- 1786: the British East India Company attempts to create a settlement in the islands, only to discover the French settlement.

- 1814: by the Treaty of Paris, France cedes to the UK Mauritius and its dependencies, including the Seychelles and the Chagos Islands, the latter of which was not specifically named.

- 1885–1888: a small force of policemen from Mauritius are stationed in the Chagos Islands, the only time a permanent official Mauritian presence existed in the islands. Mauritian administrative control over the Chagos remained minimal, except a yearly visit by magistrates from Mauritius.

- 1903: the Seychelles are detached from Mauritius to be constituted into a separate crown colony.

- 1908: Coëtivy Island is detached from Mauritius and transferred to the Seychelles.

- 1921: Farquhar Atoll is detached from Mauritius and transferred to the Seychelles.

- 1958: a ministerial system (partially responsible government) is introduced in Mauritius.

- 1959: first election on the basis of universal adult suffrage in Mauritius, won by the pro-independence Labour Party led by (Sir) Seewoosagur Ramgoolam.

- 1964: beginning of discussions between the UK and the United States about the use of the Chagos Islands for defence purposes.

- 1965 (8 November): with the agreement of the elected government of Mauritius, the Chagos Islands are detached from Mauritius to form the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). Mauritius receives £3m in compensation, as well as other concessions and UK agreement to fund future resettlement of Mauritian Chagos Islanders in Mauritius.

The anti-independence Parti Mauricien leaves the coalition government in protest against the agreement to detach the Chagos Islands: in its view, the size of the compensation package was inadequate.

The UK government agrees on a plan and timetable toward granting independence to Mauritius. - 1965 (16 December): UN General Assembly Resolution 2066(XX) “invites the administering Power [the UK] to take no action which would dismember the Territory of Mauritius and violate its territorial integrity”.

- 1967–1973: residents of the Chagos Islands are forcibly removed in stages from the Islands to the Seychelles and Mauritius, at all stages with the agreement of the governments of the Seychelles and of Mauritius, both before and after independence, pursuant to resettlement scheme agreed in principle in 1965 and in detail in 1971,

- 1968 (12 March): Mauritius becomes an independent country. Its constitution does not claim the Chagos Islands as being part of its territory.

(12 March) A defence treaty between the UK and Mauritius, one of the preconditions for the detachment of the Chagos Islands required by the Mauritian government, is concluded. - 1974: Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, Prime Minister of Mauritius, tells the Mauritius legislative assembly that the 1965 detachment of the Chagos Islands had been with the consent of Mauritius. He adds that “from the legal point of view, Great Britain was entitled to make arrangements as she thought fit and proper” even in the absence of Mauritian agreement.

- 1975: Prime Minster Ramgoolam tells the press that the UK having paid for the Chagos Islands, she could do whatever she liked with it.

- 1976: the Seychelles becomes independent.

- 1980: Prime Minister Ramgoolam tells the press that “a request was made in the [Mauritius Legislative] Assembly that we should include Diego Garcia as a territory of the State of Mauritius. If we had done that we would have looked ridiculous in the eyes of the world, because after excision, Diego Garcia doesn’t belong to us.”

- 1982: the Mauritian Militant Movement–Mauritian Socialist Party alliance defeats Ramgoolam’s Labour Party at the Mauritian general elections.

For the first time since its independence in 1968, Mauritius lays claim to the Chagos Islands through the enactment of the Interpretation and General Clauses (Amendment) Act. - 1982–1983: the Mauritian Legislative Assembly establishes a select committee to investigate the detachment of the Chagos Islands from the crown colony of Mauritius in 1965. Its final report claims that Mauritian consent was secured through UK blackmail.

- 1992: the Constitution of Mauritius is amended to claim the Chagos Islands as part of Mauritius.

- 2000–2016: litigation in English courts about the legality of the expulsion of the Chagossians from the BIOT. The question of sovereignty is not raised.

- 2015: an arbitral tribunal constituted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea declares that the UK government could not lawfully establish a Chagos Marine Protected Area because the UK had promised Mauritius in 1965, as part of the agreement to cede the Chagos Islands, that it would preserve the latter’s fishing and mineral rights in the Chagos. The tribunal declines to rule on the question of the sovereignty of the islands.

- 2017: the UN General Assembly refers the question of the separation of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius to the International Court of Justice.

- 2019 (25 February): the International Court of Justice issues its advisory opinion.

- 2019 (22 May): the United Nations General Assembly adopts a non-binding resolution supporting the ICJ’s advisory opinion.

- 2021: the Special Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea rules that the 2019 ICJ opinion had settled the sovereignty of the Chagos Islands, despite the fact that the ICJ opinion was explicitly not legally binding.

The historical record and its significance

The ICJ’s 2019 advisory opinion, the subsequent General Assembly resolution, and the ITLOS Special Chamber’s preliminary ruling do not provide any legal reason for the Government to abandon the UK’s long-settled position in relation to sovereignty over the BIOT. That long-settled position is entirely consistent with a close reading of the historical record, which makes clear the artificial and opportunistic nature of the claim by Mauritius, which has achieved some success in international institutions – the ICJ, the General Assembly and the ITLOS Special Chamber – but which should be firmly rejected by the UK.

Since it began its diplomatic and legal offensive against the United Kingdom for the sovereignty of the Chagos Islands, Mauritius has offered a simple, yet attractive story. The Chagos Islands are an integral part of Mauritius. In 1965, the United Kingdom government blackmailed the leaders of the island into agreeing to cede them to the United Kingdom, threatening to sabotage its road to independence otherwise. Under duress, Mauritius agreed to cede the islands, which it is now reclaiming as a rightful part of its territory.

But saying it does not make it so, and the Mauritian account does not withstand the most basic scrutiny. The historical record shows clearly that the Mauritian government consented to the detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius in 1965, in exchange for considerable payment and non-monetary concessions. The record shows that Mauritius consistently affirmed the validity of the agreement for a generation after its independence from the UK.

Far from being an integral part of Mauritius, the linkage of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, more than 2,000 kilometres away, arose purely as an accident of colonial history, which was then perpetuated for reasons of convenience. As even Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, Mauritius’ first post-independence leader and the man who agreed to the detachment of the Chagos in return for cash, acknowledged, the Chagos were “a portion of our territory of which very few people knew… which is very far from here, and which we had never visited”.6Mauritius Legislative Assembly, Report of the Select Committee on the Excision of the Chagos Archipelago (No. 2 of 1983), June 1983, p. 22 (hereinafter “Mauritius Select Committee”). Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180301-WRI-05-03-EN.pdf (Annex 129). The post-1982 assertion that the Chagos Islands were in 1965, and have long been, an integral part of Mauritius is simply false.

Even more cynically, Mauritius has sought to conflate the plight of the displaced Chagos islanders, which have rightly attracted widespread international sympathy, with its claim to sovereignty over the Islands, viz. its attempt to renege on the 1965 agreement to detach the islands from the bounds of the crown colony. In the years after detachment, the Mauritian government treated the Chagossians with little consideration, viewing them as interlopers to the country. As a result, many Chagossians are today opposed to the Chagos becoming part of Mauritius, and seek to have a say in the future of the islands, which Mauritius has refused to allow. Far from being the simple morality tale in Mauritius’ telling, the sorry saga reveals the degree to which the historical truth has been subverted for political ends.

Early history

Although its existence was attested to in Maldivian oral tradition, it appears that the Chagos Islands, whose existence was first noted cartographically around 1512, remained uninhabited until the 18th century, when French planters established coconut oil plantations in the Chagos Islands, using enslaved Africans as labour.

Mauritius was acquired by the United Kingdom under the terms Article VIII of the Treaty of Paris of 1814, at the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition. The Treaty stipulated, in its material portion, that:

His Britannic majesty… engages to restore to his most Christian majesty, within the term which shall be hereafter fixed, the colonies, fisheries, factories, and establishments of every kind, which were possessed by France on the 1st of January 1792, in the seas and on the continents of America, Africa, and Asia, with the exception however of… the Isle of France [Mauritius] and its dependencies, especially Rodrigues and Les Sechelles, which several colonies and possessions his most Christian majesty cedes in full right and sovereignty to his Britannic majesty [emphasis added]

The Chagos Islands were not specifically enumerated, but were treated as a dependency of Mauritius for the purposes of the Treaty, and were therefore ceded to the United Kingdom. Though their geographical position would have suggested that a linkage with India or Ceylon, the path dependent nature of colonial administration meant that the Chagos Islands continued to be nominally administered from Mauritius, despite the distance and the general lack of links between the two territories.

Thus, until the Chagos Islands (also known as the Oil Islands) were transformed into the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) in 1965, they remained a dependency of Mauritius, and were usually grouped as one of the ‘lesser dependencies’. In practice, the administrative links between the Chagos and Mauritius were minimal throughout the colonial era. Some 2,150 kilometres away from Port Louis, the capital of Mauritius (some several days’ sailing by steam), it could hardly be otherwise.

Mauritius law did not apply to the Chagos Islands unless they were specifically extended to the Chagos Islands either by proclamation or necessary implication, a reflection of the very different conditions which prevailed in both places. Mauritius’ partially elected Legislative Council contained no representative for the Chagos Islands, nor was any unofficial member (meaning a member who did not hold office under the Crown) of the Executive Council from the Chagos Islands.

The Chagos Islands were administered by officers specially appointed for that purpose by the Governor of Mauritius, essentially two non-resident magistrates. A small Mauritian police force was present on the islands from 1885 to 1888, when they were withdrawn and never reintroduced. In practice, Mauritian oversight over the Chagos Islands was minimal, the islands being almost exclusively run by plantation managers. As Mr Justice Ouseley wrote in 2003:

The [plantation] companies ran the islands in a somewhat feudal manner. The vast distance from Mauritius left the plantation managers in day-to-day charge; visits by Mauritian officials were rare and the Magistrate was at best an annual visitor. Plantation managers had powers as Peace Officers to imprison insubordinate labourers for short periods, or to detain those threatening to breach the peace.7Chagos Islanders v Attorney General Her Majesty’s British Indian Ocean Territory Commissioner [2003] EWHC 2222 (QB), at [4].

In any case, although the magistrates operated out of Port Louis in Mauritius, it was not uncommon for British administrative officials to operate out of a remote headquarters for reasons of administrative convenience, particularly as dependencies often did not offer the possibility of adequate administrative facilities. For instance, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, responsible for Basutoland, Bechuanaland, and Swaziland, was based in the Dominion of South Africa. A similar arrangement exists today whereby the Governor of Pitcairn is based out of Wellington, New Zealand (Pitcairn is a British Overseas Territory, and is not a part of New Zealand). Thus, little can be made of the fact that the magistrates operated out of Mauritius.

Contemporary colonial administrative reports underscore the minimal connection that existed between Mauritius and the Chagos Islands. For example, the 1933 annual Colonial Office report for Mauritius did not contain a single mention of the Chagos, and only had a general mention of “the dependencies [which] comprise a large number of small islands between 230 and 1,200 miles away”.8“Annual Report on the Social and Economic Progress of the People of Mauritius, 1933”, Colonial Reports—Annual No. 1685 (London: HMSO, 1934), at 2. The 1946 Colonial Office List contained two short paragraphs about Diego Garcia under the “Dependencies” sub-heading for Mauritius; but otherwise all of the report’s substantive sections, covering subjects ranging from education to posts and telegraphs to health, focused on Mauritius only.9The Colonial Office List, 1946. Comprising historical and statistical information reflecting the Colonial Empire, lists of officers serving in the colonies, etc., and other information (London: HMSO, 1946), p. 160.

Economically, links between the Chagos and Mauritius were limited. The Chagos provided some coconut by-products to Mauritius for domestic consumption, and supplies were probably transported from Mauritius to the Chagos Islands by return boat. Labourers were recruited from Mauritius for the Chagos plantations; but labourers were also recruited from places such as the Seychelles, and there is evidence that after the Second World War Seychellois contract labourers outnumbered Mauritian ones.

The nature of the colony-dependency relationship

At the core of the loose relationship between Mauritius and the Chagos Islands is the relationship of a dependency to a colony, which international actors have repeatedly failed to grapple with, though, as we will see in the next section, several judges of the ICJ, writing separately in the Chagos advisory proceedings in 2019, suggested that the ICJ’s treatment of the Islands as fully integral to Mauritius is unconvincing.

In simple terms, a dependency, in British imperial usage, was a separate colonial territory which, for the ease of administration, was attached to a larger colony. As Sir Kenneth Roberts-Wray, the undisputed authority in Commonwealth and colonial law wrote in his famous treatise:

one dependent territory may be placed under the authority of another of which it does not form part, and… the former is then usually called a Dependency of the latter.10Sir Kenneth Roberts-Wray, Commonwealth and Colonial Law (London: Stevens & Sons, 1966), p. 61. [Emphasis added].

During the British colonial era, dependencies were frequently attached, detached, re-attached from their parent territories, sometimes to be attached to another parent territory, sometimes to be given the status of a colony of its own right, and sometimes as part of the road to independence. In fact, the Chagos Islands were not the first dependency of Mauritius to be detached from it. The Seychelles, which were acquired by the British Crown at the same time as the Chagos Islands as a dependency of Mauritius under the Treaty of Paris, were detached from the Crown Colony of Mauritius in 1903 and turned into a separate crown colony. Two further islands were detached from Mauritius to be attached to the Seychelles in 1908 and 1921. The Seychelles achieved independence in 1976.

There was, of course, no suggestion that the detachment of the Seychelles, a former Mauritian dependency, implied any right at international law for Mauritius over the Seychelles under the doctrine of uti possidetis juris, the principle that newly-independent post-colonial states should generally gain independence within the existing colonial boundaries (except on one occasion in 1980, when a Mauritian government minister introduced a legislative amendment to claim the Seychelles as part of Mauritius, in order to mock opposition MPs who were seeking to introduce such an amendment claiming the Chagos Islands as part of Mauritius).

Examples of dependencies detached and attached to other colonial territories abounded elsewhere within the British colonial empire. Dominica was governed as a part of the Leeward Islands until 1940 and as a part of the Windward Islands from 1940 to 1958: it is now an independent republic within the Commonwealth. More extraordinarily, Anguilla was administered from Antigua until 1825, from Saint Kitts from 1825 to 1882, federated with St Kitts and Nevis from 1882, a part of the West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962, a part of Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla from 1967, and finally a separate crown colony (then British overseas territory) from 1980 to the present day following a pro-British, anti-St Kitts rebellion.

Another extreme case was that of British India: British colonial territories (and protectorates) which fell under the political and administrative control of British India at one point or another include Aden, Somaliland, the Straits Settlements (today Malaysia, Singapore, and one Australian territory), and Burma, all of which became independent as separate entities from India. One British East India Company possession, St Helena, is located in the Atlantic Ocean, thousands of kilometres from the Indian sub-continent. It has never been suggested that any of these territories ought to have become independent as part of India and Pakistan in 1947 under the principle of uti possidetis juris.

Similarly, the seven Trucial States in the Gulf (now the United Arab Emirates), territories under British protection, were controlled by political agents appointed by the colonial government of India until 1947 when, in anticipation to Indian independence, oversight over the Trucial States was transferred to the Foreign Office in London. At no point was it ever suggested that they should have become a part of India as part of the decolonization process (like the Indian princely states, who were similarly controlled by political agents appointed by the Government of India), despite the extensive links which existed between the two.11As Crawford notes, “Although the British Government repeatedly qualified them as ‘independent States under the protection of Her Majesty’s Government’, commentators tended to deny their independence, and even that they had any separate personality at all”, though he argued for a position closer to the former view. James Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law, 2nd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 292.

The detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius: was it blackmail?

The loose linkage between Mauritius and the Chagos Islands undoubtedly explains why in 1965, three years before its independence, Mauritius’ government agreed to the detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius in exchange for £3m and other considerations, chiefly of an economic nature. The United Kingdom also promised to cede back the islands to Mauritius when they were no longer required for defence purposes.

Mauritian ministers who were members of the Parti Mauricien opposed the agreement and left the government, but only because they viewed the compensation package as inadequate, instead of objecting to the deal in principle.12Stephen Allen, The Chagos Islanders and International Law (Oxford and Portland, OR: Hart Publishing, 2014), p. 93. See also Mauritius Select Committee, p. 33 (“On no less than three occasions, documentary evidence will establish without the least possible doubt that the P.M.S.D. was indeed agreeable, in principle, to the excision of the Chagos Archipelago but objected to the terms thereof.”) Similarly, ministers belonging to the Parti Mauricien Social Démocrate also resigned, but only because although “they all said they were agreeable in principle to detachment for defence purposes but found the terms unsatisfactory”. At a press conference following their resignation, the three PMSD ministers stressed that they would have liked to obtain a larger sugar quota for export to the United States, as well as preferential UK immigration arrangements for unemployed Mauritians.13Mauritius Select Committee, p. 13.. Sir Gaëtan Duval of the PMSD claimed to the Select Committee that he had been in favour of allowing the Chagos to be used for UK-US defences purposes but against the cession of Mauritian sovereignty over them. The Select Committee rejected his claims, based on contemporaneous documentation.

In the words of Professor Stephen Allen, a leading authority on the issue, “[t]he available evidence suggests that none of the Mauritian political parties were deeply troubled by the prospective detachment of the Chagos Islands from the colony of Mauritius.”14Allen, The Chagos Islanders and International Law, p. 93.

In the current official Mauritian version of the story, which was crystallised in 1982 through the report of a Mauritian parliamentary committee and which has been uncritically accepted by many international commentators since, the agreement of the-then premier (Sir) Seewoosagur Ramgoolam and of his government to the detachment of the Chagos Islands was obtained through a “blackmail element”, as the United Kingdom would not otherwise have agreed to the independence of Mauritius (it is interesting that not even the partisan Mauritian select committee could, on the exhaustive evidence available to it, claim that the Chagos were detached from Mauritius as a result of British blackmail, hence the far more equivocal formula of “blackmail element”).15Mauritius Select Committee, p. 37. According to that story, Ramgoolam was placed in an impossible position, as the British would have refused to support Mauritian independence without a referendum if he did not agree to the detachment of the Chagos Islands.

However, the Mauritian version does not survive even cursory scrutiny. Firstly, by 1965, the United Kingdom was in the process of divesting itself from the vast majority of its overseas possessions. Outside of Mauritius, in Africa after 1965 the United Kingdom only retained Bechuanaland and Basutoland (who became independent in 1966), Swaziland (which became independent in 1968), the Seychelles (1976), and Southern Rhodesia (whose delayed independence, in 1980, was the result of a local rebellion against the Crown). The British policy of colonial divestment, by then well-known and mostly completed, was underscored by the merger of the Colonial Office into the Foreign Office in 1966.

The fact that Mauritius took so long to achieve independence was the result of domestic divisions within the territory. A significant minority of the Mauritian population was opposed to independence and sought some form of association (or even integration with) the United Kingdom. The Parti Mauricien, whose reaction was referred to at the beginning of this section, was opposed to independence and sought a referendum on independence or association with the United Kingdom. In fact, the British government consistently rejected proposals for integration of Mauritius with the United Kingdom, as it saw no tangible benefit for the United Kingdom to such an association between the two.

Furthermore, the Mauritian ministers only publicly committed to supporting the detachment of the Chagos after the United Kingdom publicly stated its support for Mauritian independence, underlining the separate nature of the two matters. The UK announced its commitment to Mauritian independence on 24 September 1965, while the Mauritian ministers gave their agreement on 5 November 1965. Simple chronology, therefore, fatally undermines Mauritius’ current claim that UK support for independence was conditioned on Mauritius agreeing to the detachment of the Chagos Islands.

Secondly, as even Mauritian participants later acknowledged, the Chagos could have been detached unilaterally by the United Kingdom government with or without Mauritian agreement—and it is plainly obvious that the Mauritian government would have found it far easier to protest an unilateral act on the part of the United Kingdom than to protest a quid pro quo agreement to which they gave consent and legitimacy.

More crucially, this version of history rests on the unstated assumption that a majority of the Mauritian population would have voted democratically in favour of continued association with the United Kingdom in a referendum, for if a pro-independence referendum result had been the outcome the pro-independence Mauritian ministers’ hand would have been immeasurably strengthened. If the Mauritian public voted in favour of free association with the UK, this would have fulfilled the requirement for decolonization under United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1541 (XV), which provides for “free association with an independent State” as one of the three possible paths to “a full measure of self-government”.

Thus, the Mauritian government freely and knowingly agreed to the detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius. Put at its highest, the most that can be said for the ‘coercion’ or ‘blackmail’ account is that the United Kingdom might have ordered a referendum on free association, through which the Mauritian people would have had the choice between independence and free association, both of which are legal outcomes to decolonization under international law. To call this ‘blackmail’ is to do violence to the English language and to reject the right of Mauritians to determine their own future.

In fact, not only did Mauritian ministers agree to the detachment, they energetically negotiated for enhanced compensation from the United Kingdom for the move. In private, the Mauritian ministers were blunt about their negotiation strategy. (Sir) Abdool Razack Mohamed, later the first deputy prime minister of independent Mauritius, told the British government that:

If only the U.K. were involved then they would be willing to hand back Diego Garcia to the U.K. without any compensation; Mauritius was already under many obligations to the U.K. But when the United States was involved as well they wanted something substantial by way of continuing benefit.16United Kingdom record of the meeting on “Mauritius – Defence Matters”, 9:00am, 20 September 1965, p. 8. Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180215-WRI-01-02-EN.pdf (Annex 29).

Contrary to later claims from Mauritian participants, Mauritius’ main interest in the detachment of the Chagos Islands was economic, and Mauritius energetically bargained for an enhanced compensation package, which led to the cash payment from the United Kingdom to be increased from £1m to £3m. Indeed, the financial windfall was recorded in the Mauritian financial reports under the heading of “Sale of the Chagos Islands”.17Allen, The Chagos Islanders and International Law, p. 95. The faraway Chagos were, after all, only “a portion of our territory of which very few people knew”.18Mauritius Select Committee, p. 22. But the prospective economic benefits were by no means limited to cash. Nor were the substantial benefits to Mauritius (as perceived by Mauritius politicians) only economic.

The 1965 agreement between Mauritius and the UK, negotiated between 23 September early October 1965 included the following benefits to Mauritius:

(i) negotiations for a defence agreement between Britain and Mauritius;

(ii) in the event of independence an understanding between the two governments that they would consult together in the event of a difficult internal security situation arising in Mauritius;

(iii) compensation totalling up to £3m. should be paid to the Mauritius Government over and above direct compensation to landowners and the cost of resettling others affected in the Chagos Islands;

(iv) the British Government would use their good offices with the United States Government in support of Mauritius’ request for concessions over sugar imports and the supply of wheat and other commodities;

(v) that the British Government would do their best to persuade the American Government to use labour and materials from Mauritius for construction work in the islands;

(vi) the British Government would use their good offices with the U.S Government to ensure that the following facilities in the Chagos Archipelago would remain available to the Mauritius Government as far as practicable:

(a) Navigational and Meteorological facilities;

(b) Fishing Rights;

(c) Use of Air Strip for emergency landing and for refuelling civil planes without disembarkation of passengers.

(vii) that if the need for the facilities on the islands disappeared the islands should be returned to Mauritius.

(viii) that the benefit of any minerals or oil discovered in or near the Chagos Archipelago should revert to the Mauritius Government.19“Record of a meeting held at Lancaster House on “Mauritius Defence Matters”, 2.30pm, 23 September 1965. Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180215-WRI-01-02-EN.pdf (Annex 33).

Between then and 5 November 1965, the agreements in relation to several of these matters, and to reversion of the Islands to Mauritius on cessation of UK defence use, were somewhat firmed up in Mauritius’ favour.

Mauritian attitudes toward the Chagos Islands after independence

After it gained independence, Mauritius did not contest the United Kingdom’s sovereignty over the Chagos Islands for the next fourteen years. In fact, the government of the newly-independent country reaffirmed on multiple occasions that it had voluntarily agreed to cede the islands to the United Kingdom, that sovereignty over the Chagos Islands was vested in the United Kingdom, and did not wish to make any further claims to the islands. Mauritius did not raise the issue of the Chagos in the United Nations or other multilateral forums until well into the 1980s.

Mauritius’ acceptance of the detachment of the Chagos stood in stark contrast with neighbouring Comoros’ persistent protests against France’s detachment of the island of Mayotte from its territory in the run-up to Comoran independence a decade later, which have continued uninterrupted into the present day. Clearly, if its government thought that consent to the detachment of the Chaos had been obtained under duress, it could have followed Coromos’ lead: the fact that it chose not to speaks volumes as to Mauritius’ view of the binding nature of the agreement. As a matter of fact, the premier of Mauritius had been in contact with the Secretary-General of the United Nations before independence on unrelated matters concerning a dispute over the future electoral system of Mauritius, and nothing stopped him from raising the issue of the Chagos Islands with the United Nations had there been the least wish in doing so.20S R Ashton and Wm Roger Louis (eds.), British Documents on the End of Empire, Series A, Volume 5 (London: TSO, 2004), p. 184.

Far from viewing the 1965 agreement as the result of ‘blackmail’, as the Mauritian government would later claim, post-independence Mauritius political leaders repeatedly reaffirmed the validity of the 1965 agreement, rejected calls to lay claim to the Chagos Islands, and dismissed any notion that their agreement to the detachment of the Chagos had been obtained through British coercion. Opposition figures who were involved in the decision to detach the Chagos Islands also consistently affirmed that there was no blackmail or coercion involved in their decisions.

Mauritian ministers repeatedly made public statements reaffirming the validity of the decision to detach the Chagos. In 1974, prime minister Ramgoolam told his country’s legislature that:

Even if we did not want to detach it, I think, from the legal point of view, Great Britain was entitled to make arrangements as she thought fit and proper. This in principle was agreed even by the P.M.S.D. who was in Opposition at the time; and we had consultations, and this was done in the interest of the Commonwealth, not of Mauritius only.21Mauritius Legislative Assembly, 26 June 1974, cols 1946-1947. Available at https://files.pca-cpa.org//pcadocs/mu-uk/Annexes%20to%20Memorial/MM%20Annexes%201-80.pdf (Annex 71).

In 1980, some Mauritian MPs tried to amend the General Clauses (Amendment) Bill (No. XIX of 1980) to include the Chagos Islands as part of the definition of Mauritius. Sir Harold Walter, then the Minister of Foreign Affairs, was categorical that the Chagos Islands

forms part of Great Britain [sic] and its overseas territories; just as France has les Dom Tom; it is part of British territory there is no getting away from it: this is a fact, and a fact that cannot be denied; no amount of red paint can make it blue!22Mauritius Legislative Assembly, 26 June 1980, col 3415. Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180215-WRI-01-02-EN.pdf (Annex 46).

Another government minister introduced an amendment to claim the Seychelles, detached from Mauritius in 1903 and independent in 1976, apparently to mock the opposition amendment, which was not passed.23Mauritius Legislative Assembly, 26 June 1980, cols 3392-3405. Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180215-WRI-01-02-EN.pdf (Annex 46).

The same year, prime minister Ramgoolam told the press that:

a request was made in the [Mauritius Legislative] Assembly that we should include Diego Garcia as a territory of the State of Mauritius. If we had done that we would have looked ridiculous in the eyes of the world, because after excision, Diego Garcia doesn’t belong to us.24“Port Louis, telno 104 of 28 June 1980”. Available at https://files.pca-cpa.org//pcadocs/mu-uk/Annexes%20to%20Counter-Memorial/UKCM%20Annexes%2028-46.pdf (Annex 36).

It would be difficult to imagine more categorical recognitions of UK sovereignty over the Chagos Islands, which have special weight coming from the prime minister and the minister of foreign affairs of Mauritius, among others. More important still, the Mauritian ministers who negotiated both independence and the excision of the Chagos Islands were rightly adamant that they agreed to the latter for the sake of benefits to Mauritius, both general and specific:

In 1980, in a debate of the Mauritius Legislative Assembly on 25 November, the following exchange with the Prime Minister was recorded:

Mr Boodhoo: Was the excision of these islands a precondition for the independence of this country?

Prime Minister: Not exactly.

Mr Bérenger: Since the Prime Minister says today that his agreement was not necessary for the “excision” to take place, can I ask the Prime Minister why then did he give his agreement which was reported both in Great Britain and in this then – Legislative Council in Mauritius?

Prime Minister: It was a matter that was negotiated, we got some advantage out of this and we agreed.25Mauritius Legislative Assembly, 25 November 1980, col 4223. Available at https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/169/169-20180215-WRI-01-02-EN.pdf (Annex 48). [Emphasis added].

The statements of Mauritian ministers, as well as of Mauritian political leaders from different political parties with radically diverging political agendas from the period are particularly important because the ICJ simply ignored these statements in its advisory opinion, declaring baldly and without any further explanation or reasoning that:

Having reviewed the circumstances in which the Council of Ministers of the colony of Mauritius agreed in principle to the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago on the basis of the Lancaster House agreement, the Court considers that this detachment was not based on the free and genuine expression of the will of the people concerned.26Legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965, Advisory Opinion, 25 Feb. 2019, ICJ Rep. 2019, p. 95 at 137 (para. 172).

With respect, this unexplained and unsupported statement is simply unsustainable in the face of both the documentary record on the events of 1965, and in light of the later statements of the Mauritians who were involved in the talks.

The Mauritian stance only changed in 1982, when the Mauritian Militant Movement and the Mauritian Socialist Party won a majority at that year’s general elections. The new governing coalition, more radical in its politics than its predecessor, sought to claim the Chagos as Mauritian. The same year, it enacted the Interpretation and General Clauses (Amendment) Act 1982, which for the first time since Mauritius’ independence claimed the Chagos Islands as part of the territory of Mauritius, with retroactive effect to 13 July 1974. Thus, even Mauritius’ own statute books do not claim that the Chagos were part of its territory from 1965 to 1974.

In parallel, the Mauritius Legislative Assembly appointed a select committee to investigate the excision of the Chagos Archipelago. The committee interviewed all key living protagonists who were involved in the 1965 talks, which included former premier minister and Labour Party leader Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, leader of the opposition (later deputy prime minister) and leader of the PMSD Sir Gaëtan Duval, former minister of foreign affairs Sir Harold Walter, and former minister of commerce Maurice Paturau.

Despite its best efforts, the select committee on excision was unable to produce evidence that the Mauritian agreement to the detachment of the Chagos had been improperly obtained. In fact the witnesses it examined categorically denied that there was coercion involved. Sir Ramgoolam, in the words of the committee, “refused to describe the deal as blackmail”, in accordance with his longstanding position that it was not blackmail. It was to the committee that Sir Ramgoolam described the Chagos as “a portion of our territory of which very few people knew… which is very far from here, and which we had never visited”.27Mauritius Select Committee, p. 22.

Sir Harold Walter told the committee that none of the delegates at the Lancaster House constitutional talks of 1965 disagreed with the principle of detaching the Chagos Islands. Sir Veerasamy Ringadoo, who later became Mauritius’ first president, told the committee that he did not oppose the detachment of the islands at the time either, and that there was no dissent on this point among the delegates.

Nevertheless, in the face of such evidence, the committee insinuated, without any evidence, that there was a “blackmail element” to the agreement, using the aforementioned logic that the British government might have organised a referendum on independence if Mauritian agreement was not forthcoming. But as explained earlier, Mauritian society was deeply divided on the question of independence; and the organisation of a referendum to ascertain the views of the Mauritian population would have been perfectly in accord with the international law and practice surrounding decolonization, and so cannot be said to be “blackmail” in any sense, unless one takes the view that independence was the only legitimate option, a position not supported by international law.

Nor does the record of discussions between the UK and the Government of Mauritius between September and November 1965 give any support to the notion that the threat of a referendum on independence was an element in the agreement of the Council of Ministers to the excision. The statement of the UK Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, at the crucial meeting of 23 September 1965, made crystal clear to the Mauritian ministers two things: grant of independence and excision of the Chagos Islands were entirely distinct. The Mauritians readily agreed to excision, for the sake of a substantial package of benefits, including a defence umbrella after independence, UK representations to the US about Mauritian exports, guarantee of fishing rights, the benefit of any mineral or oil discoveries, financial aid in resettling displaced Chagos Islanders, several other benefits, and above all the agreement to return the Chagos Islands to Mauritius the moment UK/US defence needs permitted.

Although the Mauritian government has since the early 1980s more or less consistently maintained that the agreement to detach the Chagos was obtained under duress and therefore invalid, it has adopted the curious position that only the part of the agreement relating to the relinquishment of the Chagos to the United Kingdom are invalid, while the other parts of the agreement, which are to the benefit of Mauritius, are legally valid and enforceable. Instead, it has accepted various payments agreed upon as part of the agreement to cede the islands, and has sought to claim other benefits under the agreement as well.

Indeed, its 2015 case in front of the UNCLOS tribunal was based on the premise that the United Kingdom’s promises to Mauritius in relation to mineral and fishing rights in the Chagos are legally valid, but the same is not true for Mauritius’ agreement to cede the islands to the United Kingdom. This is, to put it mildly, a hypocritical and self-serving position. Mauritius cannot claim the benefit of the agreement while resiling from its core feature; yet this is exactly what it has done.28Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom), Award of 18 March 2015, Case No. 2011-03, Permanent Court of Arbitration, paras 390–406 and 417–428.

The treatment of Chagossians in Mauritius

There are many territorial disputes around the world; but few have acquired such a status of cause célèbre as the one over the Chagos Islands. In no small part, this is due to the fact that the inhabitants of the Chagos Islands were required to leave the Islands in the years following the creation of the BIOT, which has provoked moral indignation. The United Kingdom government, which was responsible, has since apologized and paid enhanced compensation to the islanders, as well as granted most of them and their descendants British nationality/British citizenship and residence in the UK.

Mauritius has repeatedly sought to link its campaign for the return of the Chagos Islands to the plight of the displaced Chagossians. It has engaged in symbolic gestures, such as including Chagossians in a recent flag-raising expedition to the Chagos Islands, and the current prime minister has promised that Chagossians and their descendants will be allowed to resettle in the Chagos Islands, though with no details as to how this is to be achieved, in view of the difficulty of sustaining economic activity in the islands.

But the linkage between the two issues, which has no doubt greatly helped Mauritius’ case in the eyes of the international community, is deceptive. As Milan Jaya Meetarbhan, formerly Mauritius’ representative to the United Nations, has bluntly admitted,

Over the years there have been two very different legal battles; those of the Chagossians against the UK government as UK citizens in UK courts to be allowed to resettle on the Chagos, and the international fight of Mauritius which has been about sovereignty.29Iqbal Ahmed Khan, “Mauritius: Chagos – Are we seeing an attempt at using the ‘falklands option’?” lexpress.mu, 16 January 2023, https://lexpress.mu/node/417865.

This point is especially important given that there is no consensus among the displaced Chagossians and their descendants that they want the Chagos Islands to revert to Mauritian sovereignty. Indeed, many Chagossians reacted to the opening of negotiations between the United Kingdom and Mauritius with dismay. This is hardly surprising. In the words of Stephen Allen, who has acted as a legal consultant to the Chagossians’ legal team,

The Chagos Islanders are ambivalent about the Mauritian sovereignty claim to the Chagos Islands… the decision of the elected representatives of the Mauritian colonial government to agree to the detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius in return for Mauritian independence, which was embodied in the 1965 Lancaster House Agreement; continuing British patronage in the form of a defence treaty which protected Mauritius’s external and internal security; and the role of the Mauritian State in the maltreatment of Chagossians, both in terms of the Mauritian government’s collusion in the involuntary displacement of the Chagos Islanders from the BIOT and their subsequent chronic impoverishment in Mauritius, have compromised Chagossian support for the Mauritian sovereignty claim.30Allen, The Chagos Islanders and International Law, p. 260-261.

Or as Chagossian activist Rosy Leveque puts it:

The descendants I’ve spoken to in Mauritius do not support Mauritius sovereignty over the Chagos Islands… Chagossians should be given the same respect as the Falkland Islands – a referendum. We should be given the choice to decide if we want to be governed by either Mauritius or UK. Our right to self-determination is not being respected.31Daniel Boffey, “Chagos Islanders demand say as UK-Mauritius sovereignty talks begin”, The Guardian, 2 January 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/02/chagos-islanders-demand-say-as-uk-mauritius-sovereignty-talks-begin

Laura Jeffery, an anthropologist who has studied the issue, writes that:

many Chagos islanders who were relocated to Seychelles opposed Mauritian sovereignty. From their perspective, Mauritian politics and business are controlled by Indo-Mauritians for their own interests to the exclusion of Creoles and other ethnic groups in Mauritius. In this formulation, resettlement of the Chagos Archipelago under Mauritian sovereignty would be controlled by Mauritian business interests, and Chagossians might not be given the opportunity to return to the Chagos Archipelago, or they might be enabled to return only as cheap unskilled manual labour. Furthermore, Chagos islanders in Seychelles suggested to me that if the Chagos Archipelago were Mauritian territory, controlled by Mauritian immigration laws, Seychellois Chagossians might find themselves unable to resettle there since they do not hold Mauritian passports. The solution to both of these problems suggested by Seychellois Chagossians was that the Chagos Archipelago should continue to be administered as a UK Overseas Territory, in which all UK passport-holding Chagossians would be entitled to residency.32Laura Jeffery, Chagos Islanders in Mauritius and the UK: Forced Displacement and Onward Migration (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), p. 46-47.

Despite its rhetoric to the contrary, Mauritius has excluded Chagossians from the talks with the United Kingdom. Earlier this year, Bernadette Dugasse, who was removed from the Chagos as a child, issued a pre-action letter against the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, arguing that the bilateral negotiations are unlawful as they “are being held without consulting her and the Chagossian people”. While the legal prospects of the claim are poor, it nevertheless illustrates the exclusion of the Chagossians from negotiations about the future of the Chagos.33Daniel Boffey, “Negotiations on Chagos Islands’ sovereignty face legal challenge”, The Guardian, 9 January 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/09/negotiations-chagos-islands-sovereignty-legal-challenge-talks-uk-mauritius

Another group, the Seychelles Chagossian Committee, has also asked the United Kingdom government to be included as part of the negotiations. It seeks a high degree of autonomy for the Chagos Islands if the islands are returned to Mauritius, and has asked for a referendum on whether the Chagos should remain under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom if Mauritius does not agree to this demand.34Sedrick Nicette, “Seychelles’ Chagossians seek to be part of ongoing negotiations between UK and Mauritius”, Seychelles News Agency, 19 January 2023, http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/18063/Seychelles+Chagossians+seek+to+be+part+of+ongoing+negotiations+between+UK+and+Mauritius Even Chagossian groups which do not oppose Mauritian sovereignty have complained about their exclusion from the talks.35Owen Boycott, “The UK expelled the entire population of the Chagos Islands 50 years ago. Reversing that injustice won’t be easy”, Prospect Magazine, 13 Janaury 2023. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/world/60403/the-uk-expelled-the-entire-population-of-the-chagos-islands-50-years-ago.-reversing-that-injustice-wont-be-easy

Mauritius has so far not included the Chagossians in the talks, nor has indicated any interest in doing so. In fact, high-ranking Mauritians have claimed, without evidence, that the demands of Chagossian groups to be heard are a British ploy to sabotage the talks. Arvin Boolell, a former Mauritian prime minister and leader of the opposition, has claimed that “this is a ploy to try to delay matters” to “have indefinite discussions”.36Khan, “Mauritius: Chagos – Are we seeing an attempt at using the ‘falklands option’?, https://lexpress.mu/node/417865. A Mauritian political commentator has claimed that UK-based Chagossians were being used “against Mauritius, and this referendum mostly in Crawley with Chagossians carrying UK passports seems to be the same old trick”.37Khan, “Mauritius: Chagos – Are we seeing an attempt at using the ‘falklands option’?, https://lexpress.mu/node/417865. The same outlet suggests that this is part of a ploy to use the “Falklands option”, i.e. to hold a referendum among the Chagossians about the future of the islands.

Because the issue was framed as a matter relation to decolonisation and not self-determination, Mauritius has steadfastly refused to acknowledge Chagossians as a “people” under international law, which would entitle them to self-determination and to choose the future of the Chagos Islands. As far as Mauritius is concerned, international courts have decreed that the islands are Mauritian, so that Chagossians have no further role to play (though, as will be seen in the next section, the Mauritian view is wrong).

Many Chagossians are suspicious of Mauritius given the way they were treated there after they were relocated to the island, where they encountered systematic discrimination as unwelcome interlopers, particularly as most of them were of African descent, unlike the majority of the Mauritian population who are of Indian descent. According to a 2005 report, “Chagossians have generally been considered to occupy the lowest social strata in the Mauritian and Seychellois social hierarchies.”.38David Vine, S. Wojciech Sokolowski, and Philip Harvey, “Dérasiné: The Expulsion and Impoverishment of the Chagossian People”, 11 April 2005, p. 257-258. https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/D_RASIN_Draft_THE_EXPULSION_AND_IMPOVERISHMENT_OF_THE_CHAGOSSIAN_PEOPLE/23888868/1. 50% of first-generation Chagossians in Mauritius reported discrimination in employment, while 66% reported being verbally abused from the Mauritian population.39Ibid, at p. 11. Among second-generation Chagossians, 45% report being verbally abused. So pervasive was the discrimination that in Mauritius, the word “Ilois”, used to referred to Chagossians, became a term of abuse. Unsurprisingly, Mauritius-based Chagossians suffer from extreme levels of poverty and social deprivation.

After their displacement, the Mauritian government took little interest in the welfare of Chagossians even though they were unquestionably citizens of Mauritius from the time of excision in 1965 and on and after Mauritian independence in 1968. In fact, some senior Mauritian politicians such as Sir Gaëtan Duval, the leader of the PMSD, took the view that the Chagossians were not entitled to Mauritian citizenship at all, as the islands were detached before Mauritius’ independence.40Mauritius Select Committee, p. 14.

The government accordingly did little to help Chagossians. For instance, in 1972, the United Kingdom government pursuant to the 1965 agreements on excision, paid £650,000 to Mauritius to compensate the displaced Chagos islanders living there. Lamentably, the money was only disbursed by Mauritius to the Chagossians in 1978, after months of protests by Chagossians, and after inflation had greatly eroded the value of the original sum. In the 1980s, the Mauritian government provided housing to some Chagossians: these houses were located in either a slum district or a brothel district.41Vine, et al. “Dérasiné”, p. 152.

Finally, there is mounting concern that history is repeating in Agaléga, an island dependency of Mauritius, which has been developed into an Indian military base with the agreement of the Mauritian government. Although information is difficult to obtain, there are growing concerns that Mauritius is doing to the inhabitants of Agaléga what was done to the inhabitants of the Chagos Islands five decades before. Already, inhabitants of Agaléga have reported restrictions on their movements and on what they are allowed to bring to Agaléga, which are making it harder to live on the islands; whilst the Mauritian and Indian governments have refused to divulge further information about their plans for the islands.42Yarno Ritzen, “Agaléga, a secret base, and India’s claim to power “, Al Jazeera, 2021. https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2021/island-of-secrets/index.html Unsurprisingly, many Chagossians view these developments with alarm, and fear for the future of the inhabitants of Agaléga, many of whose inhabitants are of Chagossian descent.

Next chapterParliamentary reaction to the ICJ’s advisory opinion

The ICJ’s advisory opinion was handed down on 25 February 2019. It has been raised repeatedly in the Houses of Parliament since then. The Government’s initial response to the advisory opinion was clear and correct, firmly maintaining UK sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. However, in the statement on 3 November 2022 and in subsequent statements in Parliament the Government has struck a very different tone. The Government has not quite conceded that it has an obligation to cede the Islands to Mauritius, but neither has it affirmed the UK’s legal rights. These statements raise serious concerns that ministers and their advisors have misunderstood the UK’s legal position and that the UK may conclude a treaty of cession with Mauritius on a false premise.

The parliamentary record also reveals that some parliamentarians, including at one stage the Labour shadow minister, have wrongly taken the ICJ’s advisory opinion, and other actions of international bodies, to require the UK to cede the Chagos Islands to Mauritius immediately. Some MPs, again including the Labour shadow minister, run together cession of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius with the question of whether the Chagossians should be entitled to return to the Islands. Others reason that it is the Chagossians themselves who should decide who enjoys sovereignty. Some are concerned about the damage that cession would do to the UK’s strategic interests and to the environment, although for others these are not reasons against cession as such.

The immediate parliamentary reaction to the ICJ’s advisory opinion

On 26 February 2019, in a debate about the Transatlantic Alliance, Helen Goodman MP (Labour) asked:

Yesterday, the International Court of Justice found that the UK’s control of the Chagos islands is illegal and wrong. This damning verdict deals a huge blow to the UK’s global reputation. Will the Government therefore heed the call of the ICJ to hand back the islands to Mauritius, or will they continue to pander to the United States military?

The response from the minister, Sir Alan Duncan MP, was short and sharp:

The hon. Lady is labouring under a serious misapprehension: yesterday’s hearing provided an advisory opinion, not a judgment. We will of course consider the detail of the opinion carefully, but this is a bilateral dispute, and for the General Assembly to seek an advisory opinion by the ICJ was therefore a misuse of powers that sets a dangerous precedent for other bilateral disputes. The defence facilities in the British Indian Ocean Territory help to keep people in Britain and around the world safe, and we will continue to seek a bilateral solution to what is a bilateral dispute with Mauritius.

On the same day, in the House of Lords, Lord Luce (cross-bench and member of the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on the Chagos Islands) asked the government what assessment they had made of the ICJ’s advisory opinion. The minister, Baroness Goldie, replied:

My Lords, this is an advisory opinion, not a judgment ruling. The opinion refers to our administration, not occupation. Of course we will look at the detail of it carefully. The defence facilities in the British Indian Ocean Territory help to protect people in Britain and around the world from terrorist threats, organised crime and piracy. We reiterate our long-standing commitment to cede sovereignty when we no longer need the territory to help keep us and others safe.

In response to a question from Lord Collins of Highbury (Labour), which noted the number of countries who had supported the referral to the ICJ, she added: