Authors

Content

Foreword

Rt Hon Sir David Lidington KCB CBE

Minister of State for Europe, 2010-2016

It’s more than a year since the Union Flag was hauled down from its mast outside the Berlaymont: two months since the transitional period ended. For better or worse, this country is now fully outside the European Union.

Whether you were an enthusiastic supporter of Leave or, like me, an unrepentant Remainer, our focus now has to be on identifying and then implementing policies that will, in the world as it now is, best enable our country to succeed.

This paper, which reflects work done across Policy Exchange’s research teams, explores those choices, opportunities and risks that now face both this and future governments.

Readers will have a variety of opinions about the merits of this or that policy idea. That is as it should be: the paper is a map, not a manifesto.

For me, the notion that the UK should seek first-mover advantage in new sectors and technologies is immensely attractive. The UK has the potential to be world-leading in areas such as fintech, life sciences, AI and GM – and to move with more agility and creativity than the EU in the decade ahead. Indeed, I remember arguing more than once at the General Affairs Council that too cautious an application of the precautionary principle and a sluggish approach to innovation risked driving these new industries out of Europe altogether, to the advantage of North America and China.

Freer global trade in services, another opportunity highlighted in the paper, would also benefit our economy and should be a priority in future bilateral trade agreements. I would add that, given the heavyweight role that the European Union plays in setting world trade rules, and the long-standing support for trade liberalisation of Member States like the Netherlands and the Nordic and Baltic countries, a close future relationship between the UK and EU would boost our chances of securing serious global reform.

On climate policy, UK political leaders will need to weigh up the pros and cons of divergence versus alignment issue by issue. Moving ahead of the pack to phase out petrol and diesel fuelled vehicles or to introduce local electricity pricing could help us meet our climate targets sooner and push British industry to take early advantage of the growing global market for zero carbon goods and services. On the other hand, if UK and EU Carbon Border Adjustments had incompatible standards and designs, it would be hard to avoid imposing additional friction and costs on trade, including potentially between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Other proposals, like loosening planning safeguards currently provided by the Habitats Directive, would make little difference to the relationship between London and Brussels, but be very controversial in domestic politics.

In the months and years ahead, UK leaders will have to confront many difficult judgements of this kind. Every one of the ideas identified by Policy Exchange in its paper will need rigorous, detailed analysis and discussion. Leavers and Remainers alike have an obligation to the country to haul themselves out of the trenches of the last five years and contribute to hard-headed, pragmatic debates about where our national interest lies.

Next chapterBackground

The end of the transition period on 1 January 2021 marked the introduction of new legal and trading arrangements between the UK and the EU, which will now be governed by the terms of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) and, for certain issues in Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Protocol.

The new UK-EU arrangements will continue to place some legal and practical limitations on UK action and there will be some new impediments to UK-EU trade as a result of the UK’s exit from the customs union and single market.

The Northern Ireland Protocol

Under the terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol, Northern Ireland must remain in regulatory alignment with the EU single market for goods. This means certain new checks, such as customs declarations1. HM Revenue & Customs (7 December 2020), Guidance: Trading and Moving Goods In and Out of Northern Ireland; https://www.gov.uk/guidance/trading-and-moving-goods-in-and-out-of-northern-ireland-from-1-january-2021

and agri-food inspections, are required on trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland and that Northern Ireland remains bound by EU disciplines on state aid where they apply to the movement of goods and wholesale electricity markets. Northern Ireland will remain subject to the jurisprudence of the EU’s Court of Justice where it is aligned to the EU framework.

The UK has negotiated with the EU various easements, some of which are time-limited, designed to reduce the burden on Northern Irish traders of compliance with the Protocol. However, there has been some disruption due to the new arrangements, including to fresh produce reaching supermarkets and certain horticultural products, such as seed potatoes, soil and others, which are now banned from crossing from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.2. BBC (1 February 2021), Brexit: How much disruption has there been so far?; https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/55831263

This disruption could get worse as various grace periods on checks expire in the coming months.

Political tensions have been exacerbated by the EU’s decision to impose export controls on vaccines, due to a lack of supply within the EU. This caused controversy because the original regulation also contained a provision to invoke Article 16 of the Northern Ireland Protocol – a decision later described as an error and revoked within hours.3. Article 16 allows either the UK or the EU to unilaterally override or suspend the Protocol if its application leads to “serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties”.

The Government wrote to the European Commission on 2 February 2021 with proposals to improve the functioning of the Protocol, to be discussed in the UK-EU Joint Committee, the UK-EU body responsible for overseeing the Withdrawal Agreement and the Northern Ireland Protocol.4. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957996/2020_02_02_-_Letter_from_CDL_to_VP_Šefčovič.pdf

The Government has not ruled out invoking Article 16 of the Protocol itself if problems cannot be addressed via negotiation with the EU. Given that Article 16 can be invoked as a result of a “diversion of trade”, it remains unclear how much disruption to Great Britain-Northern Ireland trade would be tolerated.

It should be noted that Northern Ireland is able to diverge from the EU in all the areas not subject to the Protocol. For example, the Protocol only covers goods not services. Meanwhile, if the functioning of the Protocol proves too problematic or unpopular, the ability to terminate the Protocol remains a democratic option after four years, due to the review and consent mechanism available to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The level-playing field

The “level-playing field” provisions of the TCA are designed to broadly uphold the existing baseline and manage future divergence in certain fields (social and environmental protections, competition policy and subsidy policy). The UK and the EU have agreed not to lower their existing standards on employment and the environment or use subsidies to unfairly distort trade and investment. As such, any dispute would only concern the effects of any changes to legislation, rather than whether UK rules are exactly the same as the EU’s. This means that the UK should have the capacity to amend existing rules as long as the effect is not trade distorting.

Meanwhile, both sides also have the right to take countermeasures, such as imposing tariffs, if they are being damaged by future divergence in subsidy policy, labour and social policy, or climate and environment policy. However, this does not prohibit future divergence, it merely sets out potential consequences if divergence results in distortion to trade and investment that is damaging to the other party. Crucially, any countermeasures are subject to independent arbitration, which means there would need to be solid justification for any EU tariffs in response to UK divergence.

A comprehensive deal but new costs on UK-EU trade

The main economic benefit of the TCA is that it ensures there are no tariffs or quotas on goods traded between the UK and the EU, where they meet the relevant rules of origin. This is significant because it is the first time that the EU has agreed a completely zero-tariff, zero-quota deal with any other trading partner (for example, the EU retains a small number of tariffs on Canadian agricultural exports). The deal therefore provides important stability for the sectors most vulnerable to a no deal Brexit, such as agriculture, automotive, aerospace and chemicals.

The UK secured other benefits for businesses compared to a no deal scenario, such as:

- Provisions to reduce the non-tariff barriers for medical products, automotive, chemical products, organic products and wine.

- Access to bid for government procurement contracts, going beyond the obligations set out in the WTO Government Procurement Agreement.

- Hauliers can continue to operate between the UK and EU, and to transit through UK or EU territory.

However, there are a number of areas where the UK’s exit from the EU’s customs union and single market will result in new frictions and costs on UK-EU trade:

- The rules of origin requirements mean some products will struggle to qualify for tariff-free access.

- There is no agreement on the mutual recognition of conformity assessments by UK bodies, which means UK manufacturers will need to have their products assessed for compliance with an EU-body, and vice versa.

- The EU refused to a mutual recognition agreement on food standards, something it has agreed with New Zealand, which would reduce the frequency of checks on food imports.

- While services provisions have been included, they do not go much beyond existing EU practice, which means there will be new barriers. These include the end of the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, although there is a process to recognise them in the future.

- Financial services are largely outside the scope of the deal and a pending unilateral decision from the EU will determine whether to grant the UK “equivalence”, which would allow UK access to certain markets. If equivalence is granted, UK divergence in these areas would be limited by its desire to maintain the status, since the EU can also unilaterally revoke equivalence.

- A temporary arrangement has been put in place to allow personal data to continue being transferred from the EU to the UK. Meanwhile, the European Commission has proposed to issue the UK with “data adequacy” decisions – a unilateral process – which would provide a smooth and long-term basis for personal data transfers for commercial and law enforcement purposes. The draft decisions of the Commission, which need to be formally approved by representatives of EU member state governments, would be valid for a first period of four years when they could be renewed after a review. 5European Commission, Data protection: European Commission launches process on personal data flows to UK, 19 February 2021; https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_661

- Maintaining data adequacy could constrain the UK’s ability to diverge significantly from the EU framework, but adequacy does not require the UK to adopt exactly the same rules as the EU.

New freedoms and opportunities

1. Governance

Subject to the limitations set out above, the UK now has a great deal of new policy flexibility. The flow of new rules and regulations from the EU has come to an end. The UK can regulate independently of the EU in the future, allowing the UK to experiment in dynamic and fast-moving sectors where it has a comparative advantage, such as the life sciences or fintech.

Brexit should allow greater transparency and accountability around UK policymaking. EU policymaking operates under a broad and often cumbersome model of consensus – including complex intuitional compromises between the Council and the European Parliament – the UK system can be more responsive in adapting to global or technological change or to correct policy failures.

Meanwhile, retained EU law is no longer supreme in the UK. The UK should systematically assess the legacy of rules and regulation that it has inherited from the EU. The UK could set up working groups to consider opportunities for improving or modifying the law in a range of fields. Several broad principles should inform this assessment, including:

- the extent to which the original EU directive and evolution of EU case law is congruent and convenient for UK legal, business and employment institutions, traditions and practices;

- to what extent does it cohere with common law principles as opposed to a European Roman civil law tradition in terms of matters such as burdens of proof and proportionality;

- the extent that evolving ECJ legal jurisprudence such as the concept of indirect discrimination interacts with wider UK legislation in unexpected, awkward or unduly costly ways;

- examining long standing regulation to ensure that it is needed and is appropriately and effectively framed for contemporary circumstances;

- and to examine regulation to ensure that it has not evolved into a form of rules that raise costs and effectively protect incumbent producers from domestic and foreign competition and the contest and challenge of new market entrants.

This could be part of a clearing up exercise whereby the government commits to continuous rule of law improvement, making sure that retained EU law works effectively after our exit from the EU. One practical opportunity is to help restore the rule of law by overhauling otherwise uncertain or open-ended (retained) EU law, further domesticating it by way of primary and secondary legislation and removing the opportunities for UK courts to exercise an over-sized role in relation to policymaking.

2. Trade

The UK can use an independent trade policy, alongside traditional diplomacy and development policies, to forge closer relationships our allies beyond the EU and among developing nations, boosting relations with the high-growth regions of the globe, and compensating for the relative decline in Europe’s economic weight.

A new tariff regime to benefit consumers and reflect UK economy

Outside the EU’s customs union, the UK can conduct a fully independent trade policy, enabling the UK to set its own tariffs and conclude its own trade deals. The UK has already liberalised its tariffs relative to those of the EU, but there would be scope to go further after bilateral negotiations with the US, Australia, New Zealand and the CPTPP are concluded. This could include removing tariffs on products the UK consumes but does not produce, such as certain foods and textiles.

Trade agreements tailored to UK strengths

Services account for around 45% of total UK exports, making it the most specialised exporter of services in the world – the corresponding EU average share excluding the UK is only 26% (in the US it is 33%).6. UK Trade Policy Observatory (1 April 2019), Hiding in Plain Sight – Why Services Exports Matter for the UK; https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2019/04/01/hiding-in-plain-sight-why-services-exports-matter-for-the-uk/

The recent UK trade deal with Japan improved on the existing EU agreement by incorporating the most comprehensive and cutting-edge digital and data provisions, supporting a wide range of sectors including finance, tech, telecoms, professional services, and creative industries.7. Department for International Trade (2019), Digital and Data Provisions in the UK-Japan CEPA;https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933990/uk-japan-cepa-digital-and-data-explainer.pdf

The UK can now prioritise liberalisation of trade in services to a greater extent than the EU did on our behalf.

Summary

This paper draws together analysis from the range of Policy Exchange’s experts – in Law & Constitution, Trade & Economics, Immigration & Policing, Energy & Environment, Health & Social Care – of the new freedoms and opportunities open to the United Kingdom under the terms of the new relationship with the European Union.

The end of the transition period on 1 January 2021 marked the introduction of new legal and trading arrangements between the UK and the EU, which will now be governed by the terms of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) and, for certain issues in Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Protocol.

Withdrawal from EU arrangements enables the UK to pursue policies or amend legislation it was previously unable to within the terms of EU membership. Equally, there are actions (such as the early introduction of Covid-19 vaccination and liberalising non-EU migration) that the UK was theoretically able to pursue while an EU member, which the political or practical logic of EU membership worked against. It can now implement these policies with greater speed and agility, unencumbered by the EU’s legal and political framework.

The new arrangements will continue to place some limits on UK action. In particular, under the terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol, Northern Ireland must remain in regulatory alignment with the EU single market for goods. This means certain checks are required on trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland and that Northern Ireland will remain subject to the jurisprudence of the EU’s Court of Justice where regulations are aligned.

Meanwhile, the level-playing field and dispute settlement arrangements in the TCA also place some practical and legal limitations on UK action. These provisions are innovative but they resemble arrangements increasingly used in other advanced trade agreements. Both sides have agreed not to lower their existing standards on employment and the environment or use subsidies to unfairly distort trade and investment. Both sides also have the right to take countermeasures, such as imposing tariffs, if they believe they are being damaged by future divergence in these fields. Crucially, any countermeasures are subject to independent arbitration, which means there would need to be solid grounds before any EU tariffs could be imposed in response to UK divergence.

The trade-off at the heart of any future UK-EU relationship has always been between UK sovereignty versus the degree of integration with EU markets and structures. Ultimately, the TCA reflects the UK’s desire for regulatory independence and the EU’s political imperative that withdrawal must come at the price of reduced access to the single market. This will inevitably impose some new friction and costs on UK-EU trade.

This paper acknowledges these difficulties. However, its primary purpose is to outline the freedoms and opportunities open to the UK under the new arrangements and provides examples of how the UK could use them to its advantage.

Governance

- An end to the supremacy of EU law over British law (subject to qualifications in the Withdrawal Agreement and Northern Ireland Protocol).

- The ability to amend or repeal retained EU law.

- Greater democratic accountability and ability to correct policy failures more quickly – the EU can take years to amend or repeal legislation.

- Flexibility and first mover advantage to act or regulate independently of the EU in the future, allowing the UK to experiment in dynamic and fast-moving sectors, such as the life sciences or fintech, where it has a comparative advantage.

- Autonomy for UK courts, and the end to oversight by the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

Trade

- A fully independent trade policy, enabling the UK to set its own tariffs and conclude its own trade deals.

- The UK has already liberalised its tariffs relative to those of the EU, but there would be scope to go further after bilateral negotiations with the US, Australia, New Zealand and the CPTPP are concluded. This could include removing tariffs on products the UK consumes but does not produce, such as certain food products and textiles.

- The UK is likely to prioritise liberalisation of trade in services to a greater extent than the EU did on our behalf. The recent UK trade deal with Japan improved on the existing EU agreement by incorporating the most comprehensive and cutting-edge digital provisions.8. Department for International Trade (2019), Digital and Data Provisions in the UK-Japan CEPA;https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933990/uk-japan-cepa-digital-and-data-explainer.pdf

- Using trade agreements and development policies to forge closer relationships with our allies beyond the EU and among developing nations, boosting relations with the high-growth regions of the globe, diversifying trade and compensating for the relative decline in Europe’s economic weight.

Economics and regulation

- The UK’s contribution to the EU budget has ended – the UK’s net contribution was approximately £11bn a year.9. Office for National Statistics (30 September 2019), The UK Contribution to the EU Budget; https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/articles/theukcontributiontotheeubudget/2017-10-31 These funds can now be spent on UK priorities.

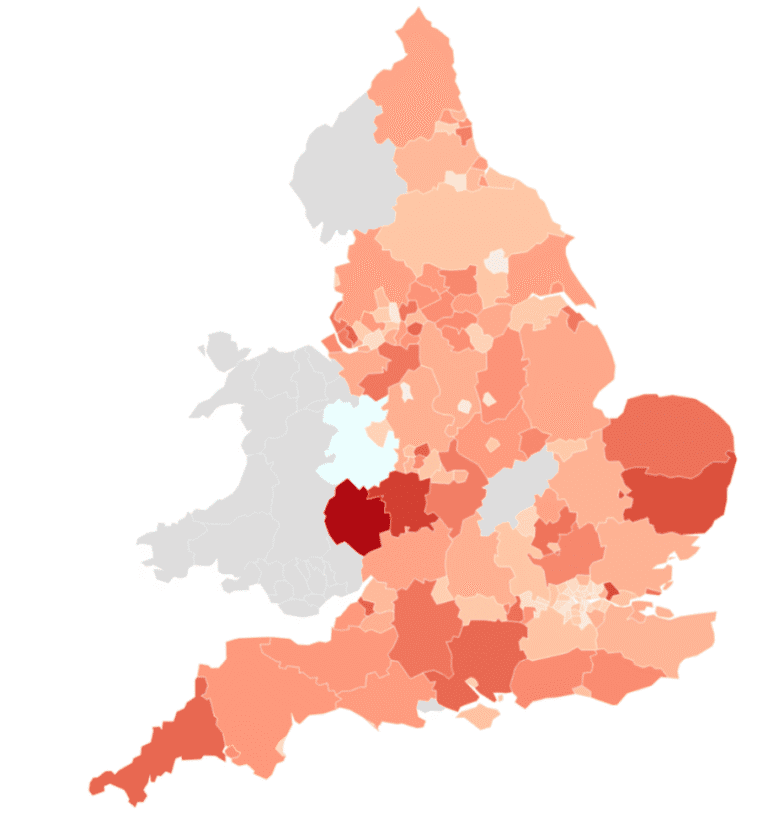

- EU state aid law no longer applies to Great Britain. A new UK regime could make it easier for the government to pursue several of its key policy objectives, particularly boosting R&D spending in economically underperforming regions, incentivising development of green technologies, subsidising transport infrastructure, assisting SMEs or reforming public procurement. Successfully designing such a regime is therefore a significant opportunity for the UK.

- Freedom to set rates and narrow or widen VAT base. For example, there is an environmental case for zero VAT on electricity bills, but maintaining the rate on gas and other fuels, in order to help the transition to low-carbon forms of heating, as well as to electric vehicles. The UK has already removed VAT on women’s sanitary products from 1 January 2021, also known as the “tampon tax”.10. HM Treasury (1 January 2021), Tampon Tax abolished from today; https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tampon-tax-abolished-from-today

- More flexibility on financial regulation, potentially including:

- Compensation – the EU’s cap on salary-to-bonus ratios is unique and an additional fixed cost compared to other jurisdictions. Diverging here would make the UK a relatively more attractive compared to the EU.

- Insurance capital requirements – the EU’s Solvency II regulations do not allow UK regulators sufficient flexibility and are not particularly well tailored to the features of the UK’s insurance sector. Reform could unlock more long-term investment, such as in infrastructure.

- Dual regime to exempt domestic firms for rules designed for international firms – the EU (CRD IV, CRR) elected to apply the same Basel capital rules to all banking and investment firms. The US, in contrast, has not. It applies the Basel rules only to its international banks. There is scope for a more flexible and proportionate approach post-Brexit.

- Other regulations, the UK might consider addressing include:

- Artists resale right to safeguard the London art markets’ competitiveness relative to other jurisdictions where the right does not apply, such as New York and Switzerland.

- The Habitats directive to reduce delays and costs currently imposed on development projects. Reforms could reflect UK’s unique environmental circumstances, rather than a one-size-fits-all EU model.

- The Port Services Regulation, which was not designed with UK ports in mind and is opposed by domestic industry stakeholders, could be repealed.

- See further sector-specific examples below.

Immigration, borders and security

- The end of free movement from January 1 has provided the political space for a deregulation of skilled migration(among other things abolishing the old cap for non-EU migration) and a closing of low skilled entry.

- The end of free movement and the skill shift in future immigration could have some quite profound demographic and economic consequences, including a possible increase to labour-saving and productivity-enhancing investment in sectors heavily reliant on low skill labour.

- EU nationals will face immigration checks of the kind that most non-EU arrivals have always faced.

- It is also likely that it will now be somewhat easier to remove EU criminals accused of summary offences, and rough sleepers and illegal workers, though immigration enforcement will need extra resources and clear legal authority.

- A new “surrender agreement” will replace the European Arrest Warrant with time restraints for responding to extradition requests. However, there are greater safeguards so that extradition can be refused if a person’s fundamental rights are at risk, extradition would be disproportionate, or they are likely to face long periods of pre-trial detention. The UK would now also be able set specific conditions for the extradition of UK nationals.

Health and social care

- The UK now has greater political flexibility and first mover advantage, demonstrated by the uniquely early introduction of Covid-19 vaccination, in contrast with the EU’s slow and “coordinated” response. The UK fast-tracked its vaccination approval while bound to EU rules, but without Brexit would have faced far greater political pressure to take part in the joint EU purchasing scheme.

- The UK can similarly accelerate licencing and reimbursement of the most innovative treatments and incentivise the development of orphan medicines.

- The UK can reconsider how EU employment law and ECJ jurisprudence has impacted on the training of junior surgeons and doctors working in acute specialisms, introducing an inflexibility in working patterns. The UK could amend the Working Time Regulations so that there is more flexibility for training – a change that the Royal College of Surgeons has called for.

- The UK has the most productive pharmaceutical manufacturing industry in Europe. The Government has made £20m available for a Medicines and Diagnostics Manufacturing Transformation Fund to encourage further companies to site facilities in the UK. More funds could be made available to encourage further companies to establish domestic supply chains.

- Post-Brexit, there is a further opportunity to strengthen medicine supply resilience, by HMG enacting legislation which would make it possible to invite new trading partners to become trusted supply partners – with agreements to keep general medical supply lines open in the event of pandemics or other emergencies, in return for a commitment to avoid new trade restrictions.

- The UK can accelerate, pre-empt and improve upon EU directives on health improvement interventions, reconsidering alcohol and tobacco pricing and the regulatory regime.

Energy, agriculture, environment and animal welfare

- There is some ambiguity in what EU rules allowed regarding the ban of petrol/diesel vehicles and local electricity pricing. It is clear that outside the EU, the could ban the sale of new petrol/diesel vehicles and it could adopt an electricity market design based on local electricity pricing, following the example of Texas, Singapore, New Zealand and others.

- The UK Government now controls its own carbon pricing regime. This means it can look to implement a carbon border adjustment mechanism, ensuring that all carbon-intensive goods consumed in the UK face the same carbon price.

- New Free Ports offer an important role for energy innovation. There is potential for the ‘regulatory sandbox’ approach to include testing new energy systems, such as hybrid renewable projects or Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

- The UK could form a coalition for a new diplomatic campaign in favour of principles-based regulation on Green Finance, using the Commonwealth, the G7 and COP26 as key forums.

- The UK’s fish stocks could be managed more sustainably, based on the latest scientific advice. This would help to protect the long-term economic and environmental sustainability of the British fishing industry.

- Replacing the CAP provides a chance to modernise our farming and reverse its long decline in relative productivity. The government should ensure ELMS includes ‘experimental’ provisions to support experimental new technologies in farming and food production, such as precision farming, alternative/lab-grown proteins, vertical farming and aquaponics.

- Allowing more GE organisms to be used in agriculture, which could reduce the cost of food whilst reducing the environmental footprint of farming.

- Ending the live export of animals for slaughter and fattening.