Authors

Content

-

- Lesson 1: A strategy is needed, but not necessarily a plan.

- Lesson 2: Drop the search for a silver bullet: there needs to be a package of measures.

- Lesson 3: Fiscal prudence is usually a necessary but insufficient condition for transformation.

- Lesson 4: Low inflation helps, but on its own it is not decisive.

- Lesson 5: Tax can matter immensely – not always, but often.

- Lesson 6: High rates of investment are usually critical: except temporarily, this requires high rates of national saving.

- Lesson 7: Competition is the key driver of efficiency: openness to international trade is a major element, but not the only one.

- Lesson 8: Once the basics of sound macro policy are in place, the reform agenda must be focused on a series of micro measures.

- Lesson 9: Leadership is crucial: but success requires more than the contribution of one key individual.

- Lesson 10: Early successes and a clear vision for the future are key to retaining political support.

- Getting through the political barriers

Foreword

Professor Leszek Balcerowicz

Former Minister of Finance and Deputy Prime Minister of Poland, and former President of the National Bank of Poland

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, which enabled the fall of communism in Central-Eastern Europe, Poland had a historic chance to change its political and economic system. The Polish economy was not only struggling but was in ruin, with Poland’s GDP per capita being lower than some African countries. Inflation amounted to 245% in 1989 and 568% in 1990. In the 1980s Poland was a recipient of humanitarian aid from the West. The situation was utterly dire. But as this powerful Policy Exchange report sets out, the economic reforms we introduced in the 1990s were crucial in setting Poland on a path towards rapid economic growth and radically higher living standards.

There is no silver bullet or generalisable blueprint for economic transformation. Each political leader must think hard about the characteristics of their own economy: what its particular affliction is, and what medicine therefore ought to be administered. We opted for a radical stabilisation and liberalisation programme in 1990. This direction has been pursued by successive governments, but at different speeds. The first element of the reform was stabilisation – curbing inflation. The second, even more fundamental was institutional transformation – including privatisation, liberalisation of the economy and as a result introducing domestic and external competition. It included, perhaps most importantly, a transformation in the role of the state which included radically shrinking the power of the central government vis-a-vis the economy and society, and the creation of genuine local government.

As a result of these reforms, between 1990 and 2022 Poland was the second fastest growing economy in Europe, after Ireland. From 1990 to 2022, Poland’s GDP per capita PPP grew by more than 220%, with an average real economic growth rate maintained at about 3.5% annually. The early adoption and fast pace of the reforms made it possible to outperform other post-socialist countries that delayed changes.

However, transformation cannot be taken for granted. Recent years have seen dangerous reversals of the reforms that enabled Poland’s leap forward. Increasing expenditures on social programmes, the halt of privatisation and weakening of the rule of law raise concerns about a return to the inefficient practices of the past. Let us hope that the new government will continue the necessary reforms.

What might be learned from the Polish experience? The authors show how many features of Poland’s economic transformation were evident in other cases of rapid economic growth. Strong leadership, a cadre of motivated allies, a strategy for change which recognises the trade-offs required and assesses the battles that need to be fought – all of these things have been common to successful projects for economic transformation. And they remind us that the politics of delivering growth is just as important as the individual policies.

Policy Exchange’s Policy Programme for Prosperity asks exactly the right questions about how to turn a nation’s economic fortunes around, and I commend this first paper in the series to the reader.

Next chapterPolicy Exchange’s Policy Programme for Prosperity

The economic performance of the UK economy has deteriorated over the last decade and a half compared to its performance beforehand. Admittedly, after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007/9, productivity growth deteriorated pretty much everywhere, suggesting that there was some common factor at work caused by the GFC. Along with Italy, however, the UK has done especially badly. Moreover, on key measures such as output per hour worked, the UK was a poor performer even before the recent deterioration.

Nor are there serious grounds for optimism about the outlook. Unless there are fundamental reforms of the economy, the most likely scenario is that the UK staggers on with very low growth, meaning very low rates of increase of living standards, as well as a continual slide down the international economic league tables, implying a weakening of British influence in world affairs.

Without a much stronger economy, the ambitions of politicians of all parties for a better economic future for our citizens will come to nought. Yet neither of the main political parties has a properly worked out plan of action to improve the economy – or even any prospect of developing one.

Our economic problems can be summed up in a single word: productivity. Everyone knows this but doing something about it is a different matter. Typically, political parties never really have a strategy for improving the level and growth rate of productivity, not least because they do not have the time to devote to thinking clearly about the problems and assessing possible solutions.

Every so often, politicians and others come up with a bold sounding mega solution that is supposed to bring salvation. But it never arrives. Either the vision is too narrow, or the supposed solution is too difficult to enact, or it is watered down, or it fails to address more than a fraction of the problem, or it ignores basic economic reality.

To have a hope of improving our performance on productivity we have to get to grips with the many factors that are holding it back. What is needed is a radical look at the underlying problems of the economy and a set of clear-eyed radical proposals to deal with them. That is exactly what this Policy Exchange programme aims to provide.

The Vision

The philosophy that underpins this venture is one of belief in the market economy. But this does not mean that there is nothing for government to do in both a micro and a macro sense. In fact, in much of the private sector economy – from housing to childcare to energy – government is integrally entwined in the functioning of these markets. Indeed, the very fact that this study is directed towards constructing an agenda of action for government should make it abundantly clear that it is not simply a panegyric to the market economy.

Some of what is wrong with the British economy is of the state’s own making; some is not. Either way, when things are as malformed and malfunctioning as they are in Britain today, leaving everything to the market will deliver, at best, the most efficient in the circumstances path to decline and disappointment. Even if an efficient and prosperous future involves more use of market mechanisms, the market alone will not be able to get us to this result. This will require a programme of action by government. That is what this Policy Exchange initiative is designed to construct.

Much of what will be discussed will be controversial – as will be its conclusions and recommendations. It will not be possible to produce the answer, which everyone accepts. But in advancing both a diagnosis and a prospective cure, at the very least this venture can hope to spark a serious debate about British economic policy and what needs to be done to improve the performance of the British economy.

Micro and macro

Sometimes, what holds a country back is essentially macro: for instance, excessive inflation, high public deficits and debt, politicised monetary policy, or an inappropriate exchange rate. There are elements of this list of macro problems in today’s economic situation in the UK but, in our view, they are not the dominant causes of poor economic performance. Once the current inflation spike has been dealt with, inflation should cease to be a major problem in the economy and the regime for deciding monetary policy, although it has its flaws, is a big improvement on the regime of politicised monetary policy-making that ruled before. Public debt is excessive but there is a plan to bring it down as a share of GDP. The exchange rate is not egregiously mispriced and the current floating rate regime is right for the UK.

Rather, the British economy suffers from a series of micro problems in each major sector. In some respects, serious problems are shared across all sectors but in many cases they are peculiar to a particular sector. Accordingly, this study takes a predominantly sectoral approach. It concentrates on key sectors of the public sector where poor performance is of major relevance to the economy overall – the NHS, the benefits system, crime and the justice system – and areas of the private sector where there is room for huge improvement – housing being a key example.

Two key macro subjects influence all sectors and are in turn affected by them, namely the level and structure of taxation and the level and type of real investment. They are covered in separate chapters. Nevertheless, the examination of major micro failings in the various sectors of the economy is relevant to them as well.

If we are to achieve and sustain a much lower rate of taxation, this will require a lower share of government spending in GDP. This will require a re-imagining of the role of the state across various sectors and a drive towards efficiency. Simply imposing across the board cuts would be stubbornly opposed, would lead to gross inefficiencies and would probably in time be reversed. Equally, sorting out the various micro problems of the economy can play a critical role in boosting real investment.

Our final chapter will draw together lessons from what has gone before and assess the relative importance of the sectoral failings that we have identified and the relative size of the benefits of the reform programmes that we have laid out. While it would be possible for governments to take a smorgasbord approach to a programme of reform and adopt one or more of our suggested measures because they seemed appropriate and/or doable, we try to show how the different areas of our programme are related and make some suggestions about inter-relationships and about sequencing.

The first subject that we address is the international evidence on how countries can achieve an economic transformation. We all know that economic transformation is difficult. Indeed, there is widespread pessimism about British governments ever being able to achieve anything at all. Yet there are a number of examples of countries being able to deliver just this. These cases are often trotted out as examples that the UK should follow. So, a study of these experiences is a good place to start our review of a detailed economic policy programme for the UK. If they can do it, why can’t we?

Next chapterIntroduction to Economic Transformation: Lessons From History

There are many examples of countries that have achieved dramatic economic transformations. Our intention here is not to produce a definitive, all-embracing examination of all of those examples. Rather, we want to examine a variety of different cases of economic transformation occurring at various points in the post-war period to see what key messages they may have for the UK today.

Accordingly, we do not examine the case of the dramatic transformation of the Chinese economy after 1978, nor of the later take-off of the Indian economy, nor umpteen other examples of drastic economic improvement in Asia or other parts of the emerging world. Those countries’ circumstances were both individual and radically removed from those that confront the UK today.

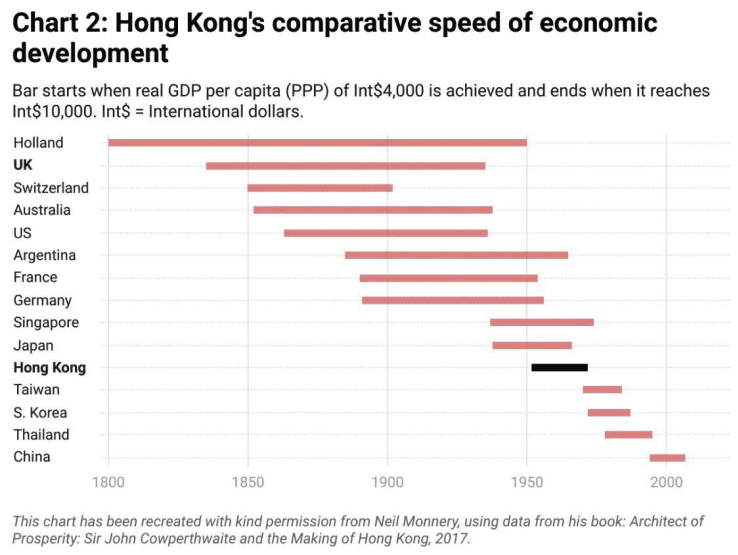

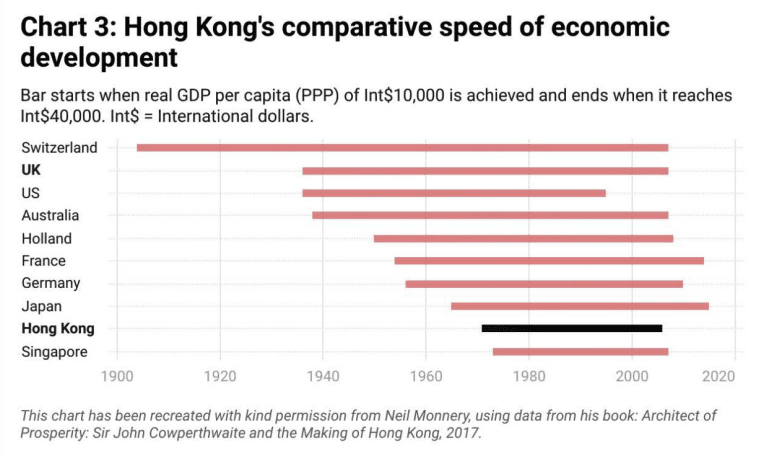

Rather, our main focus is on relatively developed economies in the west, although for reasons that should become obvious once readers have digested the sections on these economies, we do include Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea.

Similarly, the study of economic recovery after the collapse of communism is a large subject on its own and we have neither the space, nor the need, to delve deeply into this area. However, we have thought it useful to look at one successful post-communist country, namely Poland.

Arguably, we should have extended our study to include Australia and New Zealand, both of which have undergone substantial reforms of economic policy. But our list of countries was already long and we had to draw a line somewhere. Nevertheless, in later sections of this study, we will make reference to these countries’ experiences.

This study of different countries’ experience of transformation examines the following examples:

- Mrs Thatcher’s Britain – Turning the Country Round: 1983-2007.

- Germany after the War – The German Economic Miracle: 1945-1973.

- France after the War – The Thirty Glorious Years: 1945-1973.

- Ireland – “The Celtic Tiger”: 1981-2020.

- Poland – From Communism to the Market Economy: 1990-2020.

- South Korea – Interventionism plus Competition: 1963-2007.

- Hong Kong – The Free Market Rules: 1962-1988.

- Singapore – Capitalism with Socialist Characteristics: 1959-2007.

For purposes of comparison, we show in Table 1 how these countries compare in regard to the growth of GDP per capita, presented as decade averages, starting in 1950.

Each of these cases is different. The aim is to draw out whether there are any shared themes which might be of relevance to the British case. There is a great deal of published material on these examples, and we draw on it, as well as conducting some original research. In particular, we try to draw out the answer to what we consider to be some key questions which may have a major bearing on the British case:

- Was the transformation achieved in these examples the result of a pre-envisaged plan by the Government in question?

- How long into the period of transformation was it before major advances were discernible?

- To what degree did the programme of economic transformation create losers as well as winners and how was political support sustained?

- To what extent did transformation involve a fundamental restructuring of the economy as opposed to doing the same things better? Was the dominant thrust of reform macro or micro?

- What was the sequencing of the various changes that took place to make the transformation happen and was the sequencing adopted in practice in accordance with how things were originally envisaged? Was this sequencing ideal?

- To what extent did the transformations involve higher savings rates by households and/or the whole economy?

- To what extent was the transformation the work of one key person?

Summary and Conclusions

- The episodes of economic transformation that we have examined are purposely both diverse and distinctly different in economic circumstances from those that confront the UK today. Because of these differences, unsurprisingly, there is no single blueprint that emerges for the UK to follow. Nevertheless, there are many suggestive aspects of these countries’ experience that provide food for thought about what can be done to improve the UK’s economic performance, and these lead on to some key lessons for the UK, as discussed below.

- Most importantly, the experience of these countries should issue a sharp rebuke to all those in the UK who regard it as next to impossible for us to achieve a marked improvement in economic performance. In most of the cases examined, economic transformation would have been regarded as highly unlikely when the process of improvement began. This is clearly true of the Asian cases of Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea.

- Closer to home, it was by no means obvious that Ireland would be able to achieve the dramatic increases in GDP per capita that it did in fact achieve. In retrospect, it may seem obvious that Germany would recover much of its pre-war pre-eminence in key sectors, but it didn’t seem obvious at the time. Much the same is true of France.

- Meanwhile, Poland’s success has come as a surprise to most analysts – although it has had the EU level of prosperity and EU practices to converge on.

- All these cases are ones where either something dramatic had happened (France and Germany) or they were so far behind the leaders in development (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Ireland, Poland) that they had a clear path ahead. The UK’s present case in very different in that nothing dramatic has happened – just a slow relative decline. Accordingly, you might easily conclude that these other countries’ experience – particularly that of France and Germany recovering after the war – is of limited relevance to the UK’s case today. But we think this is would be a mistake. These two countries provide a rich fund of experience about the political economy of radical reform programmes and the relative roles of leadership and a sense of common purpose in achieving results.

- Nevertheless, perhaps the most encouraging experience for the UK now is the UK’s own transformation during the 1980s. When Mrs Thatcher was elected in 1979, there was widespread pessimism about the UK’s prospects. Yet within a few years the country was making decided progress relative to its nearest competitors in Europe. Moreover, it had not gone through a national trauma, although perhaps the experience of the 1970s came close to it.

From our study of these eight cases of economic transformation, 10 clear lessons emerge. We lay them out and then explain them below:

- Lesson 1: A strategy is needed, but not necessarily a plan.

- Lesson 2: Drop the search for a silver bullet: there needs to be a package of measures.

- Lesson 3: Fiscal prudence is usually a necessary but insufficient condition for transformation.

- Lesson 4: Low inflation helps, but on its own it is not decisive.

- Lesson 5: Tax can matter critically – not always, but often.

- Lesson 6: High rates of investment are usually critical: except temporarily, this requires high rates of national saving.

- Lesson 7: Competition is the key driver of efficiency: openness to international trade is a major element, but not the only one.

- Lesson 8: Once the basics of sound macro policy are in place, the reform agenda must be focused on a series of micro measures.

- Lesson 9: Leadership is crucial: but success requires more than just one key individual.

- Lesson 10: Early successes and a clear vision for the future are key to retaining political support.

Lesson 1: A strategy is needed, but not necessarily a plan.

In our eight case studies, there is a wide variety of approaches to planning. South Korea planned intensively, France did so indicatively, Singapore guided its development, Germany knew where it was going, but Hong Kong had no plan at all. Ironically, Mrs Thatcher had a financial plan which was supposed to give confidence to the markets but she had no plan for the real economy.

She did, though, have a clear strategy for economic policy, that is to say, a clear view of what needed to be done, and this had been thought through carefully by a group of leading figures in the Party while they were still in Opposition. The restoration of macro stability, reducing inflation and making fiscal policy sustainable, came first. Thereafter, the key elements of her reform package evolved naturally and the limits – e.g. no fundamental reform of the NHS – continued to be observed.

Even if there is no plan as such, there needs to be such a clear strategy because successful transformation of an economy requires that a consistent policy be sustained for a prolonged period. Otherwise, a government risks being blown hither and thither by the changing winds of politics. The temptation will always be to court easy, short-term popularity without addressing the country’s long-term, structural problems. Moreover, a clear strategy helps a government to retain political support through difficult times. (See Lesson 10 below.)

Lesson 2: Drop the search for a silver bullet: there needs to be a package of measures.

It has been a feature of British post-war policy-making that the economic establishment has tended to believe that there was a single underlying cause of our relatively poor economic performance and accordingly that there was a single “silver bullet” solution. At one point, joining the EU was widely thought to be the silver bullet. Ironically, decades later, some analysts and commentators believed that leaving the EU was the silver bullet. Incredibly, some now seem to believe that rejoining the EU offers a one-stop, radical solution to our troubles.

At various other times, a lower exchange rate or a change of exchange rate regime, or the conquest of inflation, have been believed to be silver bullets.

What does the international evidence suggest about silver bullets? For most of our fast-growing countries, the solution was not one measure or set of measures but several. Perhaps one clear exception to this pattern is Hong Kong, where the silver bullet was simply to allow the unfettered market to have free rein. But even here, this was accompanied by a tight fiscal policy which built up a substantial fund of investments for the government. (See Lesson 5 below.)

In all the other cases studied, rapid growth involved several different elements. This was even true of the Thatcher Revolution of the 1980s, once the government had brought inflation down and got over its monetarist obsession.

This makes perfect sense. When an economy has been malfunctioning for some time, its failings are likely to show up in a number of different areas. This also ties in with the analytical approach taken in this study, namely to examine several key areas where the British economy appears to be under-performing. We will identify those reforms that would make the greatest difference.

Lesson 3: Fiscal prudence is usually a necessary but insufficient condition for transformation.

Fiscal prudence has been a factor in the economic success of Hong Kong and Singapore. More strikingly, its opposite, fiscal imprudence, has been a significant factor in many countries’ failure. This was surely true of the UK’s experience in the 1970s when the dire state of the public finances contributed to an atmosphere of revolving crisis.

By contrast, by the mid-1980s, with the fiscal position much improved, UK fiscal policy contributed to a sense of greater stability. As it turned out, however, there was to be another bout of high inflation at the turn of the decade, and another period of fiscal stringency in the early to mid-1990s.

Fiscal policy can also be of key relevance for countries trying to deal with a tendency for consumers’ expenditure to leap ahead. Tighter fiscal policy helps to restrain inflation at lower rates of interest, thereby helping to keep the exchange rate competitive, and limiting the extent of any deterioration in the current account of the balance of payments. And it is highly relevant to the rate of national savings. (See Lesson 6 below.) Yet, putting the public finances on a sound footing is not enough, on its own, to transform an economy.

And, as so often, South Korea is in a different category. It is an example of a country that has transformed itself despite experiencing, in its early years of rapid development, pretty lax fiscal and monetary policies.

Quite apart from the question of public sector deficits, there is the matter of the share of government spending in GDP. There are examples of successful economies with quite different levels of government spending in relation to GDP, from Singapore’s 15% and Hong Kong’s 20% to France’s 40-50%. Yet clearly, as a matter of arithmetic, if a country is to have a low ratio of tax to GDP without a budget deficit, then it must have a correspondingly low ratio of government spending to GDP.

If a reforming British government seriously wanted to move the UK to a much lower rate of taxation, then it would have to have a plan for a substantial reduction in the share of government spending in GDP.

Lesson 4: Low inflation helps, but on its own it is not decisive.

In virtually all our cases, transformation occurred against the backdrop of low inflation. In the cases of Germany and France in the early years at least, this was partly a reflection of the global economic conditions of the time. But in Germany, throughout the period of transformation and beyond, there was an institutionalised hatred of inflation. After a while, as confidence in low inflation bedded in, the associated feeling of stability surely contributed to Germany’s economic success.

Under Mrs Thatcher, the UK turned its back on the rampant inflation of the 1970s but she did not manage to achieve lastingly low inflation in the UK. The strong economic revival in the second half of the 1980s saw inflation resurging.

The clear outlier is South Korea, which prospered despite experiencing rather high and quite volatile inflation.

But, as with fiscal prudence, although the establishment of low inflation can remove many inefficiencies that high inflation engenders, in and of itself it will not deliver economic transformation. High inflation is often a symptom rather than a cause of deep malaise.

What Mrs Thatcher achieved in improving British economic performance was not mainly down to lower inflation but rather to the series of micro reforms that she introduced which increased the tempo of competition and boosted efficiency. (See Lessons 7 and 8 below.)

Lesson 5: Tax can matter immensely – not always, but often.

Among our eight cases, there are three examples where tax has played a very major role in promoting economic success – Hong Kong, Singapore and Ireland. This is less clear in the other cases.

It is not even clear in the case of the UK in the 1980s. It proved devilishly difficult to reduce the average tax rate even under a leader like Mrs Thatcher who strongly believed in lower taxes. By the end of her tenure, the tax to GDP ratio was only some 4% of GDP lower than it had been when she took over. This was not enough to transform the UK into a low tax economy. Moreover, the tax-take quickly rebounded. It is difficult to see Thatcher’s reduction in the tax-take as a leading force behind the decided improvement in economic performance during the 1980s, continuing into the 1990s.

What mattered much more, though, was the restructuring of the tax system and, especially, the reduction, in two bites, in the top rate of income tax from 83% to 40%. This contributed to a transformation of incentives and a radical change in the business and social climate.

In Ireland the establishment of an ultra-low rate of corporation tax has transformed the country’s attractiveness for multinational businesses, which has been a key factor behind its success.

In two of the countries examined – Singapore and Hong Kong – quite apart from the low level of taxation, the simplicity and stability of the tax system has been a key feature. This has allowed businesses and households to plan with some confidence that tax changes would not scupper the advantages of undertaking a particular course of action.

In contrast to nearly all other governments which have to pay out a significant part of their tax revenues in debt interest, the Hong Kong and Singapore governments receive a very large sum each year from their investments. For any given level of government expenditure, this extra source of revenue allows them to operate with lower rates of tax.

The fact that two of our countries, Germany and France, managed to achieve high rates of growth in their transformation years without operating with ultra-low tax rates is potentially misleading. In both cases, two overwhelming factors at work in effecting a transformation were recovery from the war and the transfer of labour from low productivity employment in agriculture and services. As long as the tax system was not completely dysfunctional, these structural factors were going to lead to rapid growth, even if tax rates were relatively high.

Moreover, although France has a reputation as a country of high public spending and high tax rates, these features were nothing like as prominent during France’s years of rapid economic growth. Rather, government spending started to rise markedly as a share of GDP from the 1970s onwards, after France’s “thirty glorious years”.

It is noteworthy that in recent decades, when the benefits of post-war recovery and labour transfer were exhausted, the growth rate of both economies has slowed markedly. Admittedly, even the low tax economies of Singapore and Hong Kong have also slowed but they continued to grow faster than most developed economies and continued to show marked economic dynamism.

Lesson 6: High rates of investment are usually critical: except temporarily, this requires high rates of national saving.

In all our examples, economic transformation was accompanied by, and partly facilitated by, strong investment, certainly by the private sector and often by the public sector as well. The British case under Mrs Thatcher appears to be an exception but, by British standards at least, investment was strong during the peak Thatcher years.

Of course, the quality of investment matters a great deal as well as the quantity. Wasteful investment amounts simply to consumption – but without the enjoyment. In the UK we have a history of making some poor public sector investment decisions, or not making them at all, as with Heathrow’s third runway. All other countries in this study seem to do a better job of this.

In the private sector, to a considerable extent, success breeds success. Private investment would be stimulated by businesses having confidence that government policy would be stable and directed at the long term. This would sharpen the private sector’s appetite for risk and encourage it to think and act long-term.

How a higher rate of investment links with a country’s savings behaviour does not receive the attention that it deserves. If a country is to enjoy strong investment then, unless it borrows extensively from abroad, which brings its own problems, it has to find domestic sources of finance. It is notable that in East Asia, private sector savings rates have been high, enabling high rates of investment to be financed domestically. Indeed, saving has been so strong that these countries have all run significant current account surpluses, that is it say, they have been exporting savings abroad. Within Europe this is also strikingly the case with Germany.

By contrast, the UK has a problem with an endemically low rate of personal savings, combined with a low rate of investment. If the latter is to be increased, surely a requirement for a much better growth performance then, unless the current account deficit is to widen further (which would be a decidedly bad idea), then the UK must make room for this investment by constraining public expenditure and/or private consumption. Potentially, both of these are unpopular but restraining private consumption is probably more so. The way to minimise the extent to which a consumption squeeze is necessary lies in containing public non-investment spending.

Lesson 7: Competition is the key driver of efficiency: openness to international trade is a major element, but not the only one.

In nearly all our cases, the growth of international trade has been a feature of their experience and a major contributor to their success .

Yet again, South Korea is a case on its own. It developed behind a tariff wall designed to shelter and develop so-called “ infant industries”. Even here, though, protected companies were driven to export and there was intense competition between different Korean companies. The weakest went to the wall.

In most of our cases, success in export markets has been a key feature. This is true of Germany, Singapore and Hong Kong. In all these countries, the current account of the balance of payments was in surplus. This was not true for South Korea up to 1976, but it was true afterwards.

For most countries, heavy involvement in international trade has been a key driver of efficiency. Not only does it enlarge the size of the market for domestic producers, thereby enhancing the scope for economies of scale, but it also increases competition in domestic markets. In fact, it acts as a sort of Competition Policy.

For Poland, however, the main factor making for increased efficiency was the switch from public to private ownership as a result of the privatisation drive – which had also featured prominently in the factors making for increased efficiency in the UK under Mrs Thatcher.

For the UK now, the fact that this privatisation drive is long behind us, plus the UK’s already heavy exposure to international trade, argue in favour of the idea that the UK economy is pretty competitive internally. However, that is not necessarily true of all parts of the service sector. Moreover, compared to the rapidly growing countries of Hong Kong and Singapore, the UK has a large public sector where there are next to no competitive pressures.

The UK is the world’s second largest exporter of services. But she could be even more successful in this sphere. The success of Hong Kong and Singapore pleads the case for low taxes but other features of a country’s domestic economy are also important to make it attractive for international businesses to locate there, to retain key personnel and to make its services compete effectively in world markets.

These include factors such as the efficiency of the transport system, the effectiveness of public administration, the cost effectiveness of regulatory systems, the good functioning of the housing market, low crime and many more. In many cases, for a country like the UK, the key to achieving improvements lies with making markets work better, or even in introducing markets where none currently exist. (See Lesson 8 below.)

Lesson 8: Once the basics of sound macro policy are in place, the reform agenda must be focused on a series of micro measures.

In some of our cases, there was a considerable contribution from good, conservative, macro policy-making. But this was not true of South Korea and, strikingly, it wasn’t entirely true of Mrs Thatcher’s Britain.

Of course, gross errors of macro policy can scupper an economy. But, starting from where we are, it is unlikely that tweaks to the macro policy regime – changes to the inflation target or the fiscal rules, for instance – can deliver the keys to economic success.

In all our cases, including Mrs Thatcher’s Britain, the major contribution to promoting economic growth was made by good micro policy-making. This points the way for the UK today. In contemplating the way forward, a reforming UK government would need to get into the weeds of the British economy, into the detailed workings of its under-performing sectors. This may include, as far as its actions are concerned, getting out of those workings. In many cases, government intervention is part of the problem, not the solution. At the very least, government interventions, including regulatory regimes, must be reviewed in relation to their effect on economic performance. But there are other cases, such as road pricing, where a proper market does not currently exist and where it could only come into being as the result of government action.

Lesson 9: Leadership is crucial: but success requires more than the contribution of one key individual.

In all but one of the cases studied, economic transformation enjoyed strong leadership from the top, with one key individual driving things forward: Mrs Thatcher in the UK, Jean Monnet in France, Ludwig Erhard in Germany, Lee Kwan Yew in Singapore, Sir John Cowperthwaite in Hong Kong, General Park in South Korea and, arguably, Leszek Balcerowicz in Poland. Only Ireland lacked an outstanding figure without whom the growth push probably wouldn’t have happened.

But this does not amount to a case for the UK to set off in search of a transformational leader. This would be the search for a silver bullet in human form. In any case, transformational leaders cannot really be searched for: they just appear. More positively, in all our eight cases, there was a cadre of politicians and officials who shared a common goal. This was even true in the case of Mrs Thatcher.

It is especially noteworthy that in some key examples, the quality of the civil service was critical. This was true of Singapore and, strikingly, it was also true of free-wheeling, pure capitalist Hong Kong. One of the key advantages enjoyed by France in the post-war period has been the technical expertise of its senior civil servants who have been able to make key decisions effectively and to co-operate with business leaders in pursuit of economic success.

If the UK is successfully to pursue a programme of economic reform it will probably require a fundamental restructuring and reform of the civil service.

Lesson 10: Early successes and a clear vision for the future are key to retaining political support.

Mrs Thatcher’s position was unique. She won power in 1979 but initially she was in a precarious position politically. She won two stunning election victories in 1983 and 1987 against weak and divided opposition. This enabled her to push through and sustain radical and unpopular policies. But even she was ultimately vulnerable and she was deposed in 1990. So she had only 11 years as Prime Minister. 11 years is, by British standards, a very long period in power but this is short compared to the periods over which our three strong Asian leaders effected their economic transformations. And out of her 11 years in power, she enjoyed political dominance for only 6 years (from 1983 to 1989).

Our three Asian examples all benefitted from having powerful leaders who were not constrained by all the usual factors that apply in democratic systems. This wasn’t the case for France and Germany but at least they had the recent experience of the war to act as a spur and unifying force. And Poland had the spur of the adjustment from communism to a market economy and the escape from the Russian sphere of influence. It also had the lure of future EU membership to bind society together.

How could a country like the UK muster and sustain the political support necessary to persevere with an extended programme of radical reform? After all, it would be impossible to prevent some people from being short-term losers from the programme.

It would be important to try to ensure that the gains from economic improvement were widely distributed. Where there are major losers from a reform programme, effective compensation can help to sustain support. A carefully constructed programme of tax reductions could also help to retain support, as could the wider spread of property ownership.

Over and above this, in our view, it is important that, as reform progresses, there are some early successes in order to retain confidence and sustain political support. In addition, it is important that there should be a clearly articulated vision for future measures and a shared understanding of how these are going to deliver economic benefits for everyone.

Getting through the political barriers

Even so, and even If it were clear what needed to be done to radically improve economic performance, the political barriers against achieving something meaningful are huge. How could they be overcome? In a democracy like the UK, there are four possible routes:

- A coalition government is formed by the major political parties, pursuing a policy of national economic resurgence.

- One political party achieves such dominance that it is able to develop policies for the long-term and to sustain them across an extended period.

- A consensus develops across the main political parties to such an extent that if one party takes over from another in government, much the same reform policies are pursued.

- One political party, on winning power, sets out with a phased programme of reforms. Early successes on the first stages build support for further changes and so radical reform proceeds in a step-by-step manner.

The first of these, a coalition government dedicated to economic reform, does not look like a realistic prospect. In the British system, coalition government does not come easily. True, the wartime coalition is generally reckoned to have done a good job but those were exceptional circumstances of great national peril amidst general agreement about what needed to be done, namely to defeat Germany. Even then, the coalition only lasted for 5 years and once the war was over, normal politics resumed straightaway.

The Coalition Government of 2010-15 did a reasonable job, although it was no radical reformer of the UK economy. Anyway, it only lasted for five years. Serious reform of the UK economy is a project for at least 10 years, and more like 20.

The second route, namely political dominance by one party seems more feasible but it is not at all clear that any of the UK’s political parties could achieve such dominance, and sustain it, let alone knowing what to do with its power anyway, unless it is by adopting the fourth approach, as discussed below.

Similarly, the third route, whatever its attractions, does not seem within reach in current circumstances. But perhaps it could be within reach through a merger with the fourth route, that is to say, if a government started to deliver economic success, bit by bit, then either it might become dominant in government for a sustained period or the opposition parties could adopt its approach so that whoever was in power did not matter very much, rather in the way that happened after Mrs Thatcher’s fall from power in the UK.

So, the best hope for getting a sustained economic revival in the UK rests with the pursuit of a reform agenda, proceeding bit by bit, and delivering successful outcomes along the way in the context of a clear strategy for economic reform. This would then help to build confidence and support for further measures in such a way that an early reversal of the reform strategy was not politically attractive, whoever was in power.

Policy Exchange’s Policy Programme for Prosperity aims to lay out just such an agenda for reform.

Next chapterI Mrs Thatcher’s Britain – Turning the Country Round: 1983-2007.

The dates of Mrs Thatcher’s period as Prime Minister are a matter of history – 1979 to 1990. Yet the dates of the transformation of the UK through her policies are a matter of conjecture and dispute. Her reform programme began straightaway upon taking office, but the immediate macro performance of the economy was dire. It wasn’t until after her second election victory in 1983 that things started to look a lot better and not until after the third victory in 1987 that the economy was really motoring. It was then that people spoke of the Thatcher Revolution.

And establishing the end date is also difficult. It is probably best to date the period of transformation according to the rate of growth of per capita GDP relative to the rest of the EU and other leading developed countries. On this measure, the UK started to outperform a few years into Mrs Thatcher’s period in office and, with a slip at the beginning of the 1990s, this continued under Prime Ministers Major and Blair. But it came to an abrupt halt in 2007/9 with the onset of the GFC.

The strategy for transformation

During the Conservatives’ period of Opposition in the late 1970s, Mrs Thatcher developed a clear set of principles on which the economic strategy would be based. The strategy was hammered out by a set of close associates and was accepted by her inner circle.

This was pretty unusual. In his much referenced paper known as the “Stepping Stones Report”, one of her senior advisers, Sir John Hoskyns, wrote: “Strategy can be defined, for political purposes, as “ the careful thinking we wish we had done two years ago, but don’t have time to do today”.1Available from the Thatcher Archive at Cambridge University, p 3. But Mrs Thatcher’s government was different. It did have a strategy. Senior figures, including Mrs Thatcher herself, had done the thinking.

It is difficult to over-estimate the power and authority of Mrs Thatcher in her pomp. And it is difficult to believe that anything quite like the Thatcher Revolution could have happened without her. Yet, for all that, this was no one woman band. The Thatcher Revolution was the work of several key people, including especially her chancellors, Sir Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson, and also Norman Tebbit, Sir Keith Joseph and Cecil Parkinson.

Although there were differences of opinion on some issues, such as mortgage interest tax relief, attitudes to the EU and the Poll Tax, there was a strong cadre of ministers who were united behind the Thatcher reform agenda.

The primary intellectual driver was Sir Keith Joseph and, through him, the strongest intellectual influence was Friedrich Hayek. In essence, Mrs Thatcher and her acolytes believed that the UK had been weakened by its lurch towards collectivism in the post-war period. This began under a Labour Government immediately after the war, but it was largely endorsed by, and continued under, Conservative governments.

Accordingly, breaking away from this approach entailed conflict, not only with the Labour Party but also with much of Mrs Thatcher’s own Conservative Party as well. Indeed, throughout the first few years, a considerable number of Conservative MPs, as well as many Cabinet ministers, wanted to oust her and to stage a complete about-turn in economic policy.

And you can understand why. Her economic policy was deeply unpopular in the country. That was partly because many saw it as unjust and uncaring but also it was because for a long time it did not seem to be working. The policy was supposed to reduce inflation but in the first months inflation rose, as Chart 1 shows, thanks to a combination of the rise in global oil prices, the increase in wages in the wake of the Clegg Commission’s Report on public sector pay and the effects of the near-doubling of VAT in the Conservatives’ first budget.

Moreover, the variable on which the whole strategy of inflation reduction was pinned, namely the measure of the broad money supply known as Sterling M3, continued to expand rapidly, despite interest rates being increased in 1979 in two stages from 12% to 17%, in an attempt to reduce the rate of monetary growth. (See Chart 2.) Unsurprisingly, the effects on the housing market and on many individual home-owners were severe.

And the effects on the real economy were devastating. As Chart 3 shows, unemployment continued to climb throughout the first 5 years, reaching a post-war record of nearly 12% in 1984, compared to 5.5% when the Conservatives took office in 1979. The nightly television news, then regularly watched by millions of families across the country, was dominated by stories about factories closing and businesses contracting or going bust. The aggregate GDP statistics showed a peak to trough decline in output of more than 5%, making this the then deepest recession since the 1940s.

The effects were very unevenly distributed across the country. Many parts of the Midlands and the North were devastated by the closure of businesses on which entire communities depended.

Meanwhile, most of the economic establishment was against these policies – and that included senior figures in the Treasury and the Bank of England. In response to the fiscally contractionary budget of 1981, a letter was sent to The Times newspaper, complaining about these policies, signed by no less than 364 economists (not including the authors of this study). Ironically, it was just about at this point that the economy started to recover.

And much of big business was opposed to the Government as well. In November 1980, Sir Terence Beckett, the head of the employers’ organisation, the CBI, who in those days would normally have been expected to be supportive of a Conservative administration, promised “a bare-knuckle fight” with the Government.

Politically, the Government was helped by the fact that the opposition Labour Party was weak and poorly led. And it then had the apparent good fortune of seeing the Labour movement split as the breakaway Social Democratic Party (SDP) was formed in 1981. But even this was of limited help because this new party soon soared to a commanding position in the polls. It attracted not only disillusioned Labour Party supporters but also many disillusioned Conservatives as well. For a time, it seemed that in a general election the SDP was going to win a majority of seats in parliament.

Given the scale of the opposition to her government and its policies, therefore, in her first few years, Mrs Thatcher’s freedom of manoeuvre was extremely limited. It was only after the victory over Argentina in the Falklands War of 1982, and her stunning victory over Labour in the general election of 1983, that her political position was secure and she had a more or less free hand to push strongly ahead. Her position was further consolidated by the victory in the miners’ dispute of 1984/5 and the subsequent general election victory of 1987.

Yet not long after this victory, opposition to Mrs Thatcher and her policies began to intensify. This was partly because they were widely seen as harsh and her style as dictatorial and insensitive, but also partly because of her anti-Europeanism. But the real killer was her strong belief in the Community Charge, which was widely referred to as “the Poll Tax”. This eventually undermined her support so much that she was effectively forced to resign in November 1990.

Meanwhile, inflation had risen alarmingly and interest rates had to be raised to 15% to try to rein it in. Moreover, just before she left office, Mrs Thatcher was forced to accede to the UK joining the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), the antecedent of the euro, in October 1990. For the succeeding two years, the economy was devastated, inflation was still high, interest rates were in double figures until May 1992, house prices were falling and unemployment was rising.

At this point you could have been forgiven for believing that the “Thatcher Revolution” was over, if it had ever been more than a mirage in the first place. Yet, as we show below, the effects of the Thatcher reforms could be seen in the UK’s economic performance for almost twenty years after her departure from office.

The Policy Programme

Mrs Thatcher and her close advisers and colleagues had the ambition of halting and reversing Britain’s relative economic decline. To achieve this, they focussed on eight key objectives which they saw as critical to improving economic performance:

- Reducing inflation;

- Weakening the trade unions, thereby reducing their ability to disrupt businesses and getting them out of their close and privileged position in government;

- Reducing public borrowing and reducing the weight of public debt;

- Reducing the size of the state and its role in the economy, including eschewing state support for both ailing firms and industries and potential successes (“picking winners”) 2In the event, the policy of abandoning all state support was not always rigidly adhered to. See Sir Geoffrey Owen’s paper “Where Now For UK Industrial Policy”, Policy Exchange, London, 2024. ;

- Reducing the average rate of tax and reforming the structure of tax so as to minimise distortions and boost incentives to work, save and invest;

- Privatising the large parts of British industry that were in state ownership;

- Increasing competition;

- Attracting Foreign Direct investment (FDI).

The priority attached to these objectives and the intensity with which they were pursued changed over the years that Mrs Thatcher was in office but none of these objectives was abandoned, or even appreciably watered down. To that extent, therefore, there was a consistency of vision across the period.

Sequencing

Mrs Thatcher and her inner circle had a clear idea about sequencing. First and foremost, they wanted to bring the inflation rate down, which they did, albeit there was some slippage at the end of the 1980s, as Chart 1 shows.

Although they desperately wanted to reduce the general rate of tax, they believed that it was first imperative to bring the public finances under control. This meant a tightening of fiscal policy which initially involved an increase in the tax-take as a share of GDP. Indeed, the share did not start to fall until 1982/3. (See Chart 4.) Similarly, as Chart 5 shows, the share of government spending in GDP initially rose. (We comment on fiscal policy in more detail later.)

Interestingly, although the privatisation of state-owned businesses was begun with the privatisation of BP in 1981, it was not initially a top priority. (This is not true of the sale of council-owned houses to their existing tenants, which was a key objective early on.) Privatisation did not figure in the 1979 manifesto and hardly figured in the manifesto for the 1983 election. Its beneficial effects on economic performance were largely stumbled upon. Privatisation was first envisaged primarily as a way of raising money for the Government and thereby reducing the size of its borrowing requirement.

In the event, largely because of the privatisation programme, employment in state-owned corporations fell from 8 million to 3 million and their contribution to GDP fell from 10% to less than 5%.3Russell Jones, The Tyranny of Nostalgia, London, 2023, p 83.

This not only had a beneficial effect on efficiency but it dramatically reduced the percentage of the workforce that was unionised and radically reduced the share of the economy taken up by enterprises whose ultimate paymaster was the state.

The Thatcher government was acutely aware of its potential weakness in relation to the miners’ union, the NUM. It had played a key role in bringing down the Conservative government led by Edward Heath in 1974 and it continued to exercise a strong hold over the Labour Party. Strange as it is now to imagine, but in those days dependence on coal was seen as critical.

One of the smartest things that the Thatcher government did was not to take on the miners early on and instead to concede to their demands and then to use the breathing space to build up coal stocks at the power stations. This meant that when the miners went on strike in 1984, the power stations had enough coal to continue producing power for many months, while the strikers had to carry on under increasingly difficult conditions. They eventually wilted.

Another key element of the Government’s approach to sequencing was the absence of major reform of the NHS. Not that Mrs Thatcher and her ministers were under any illusions about the failings of this service and the strains that these were placing on the public finances and overall economic performance. They merely judged that the NHS figured too large in the nation’s affections and that most voters would be fearful of any attempts radically to reform it. Across the Thatcher years, the share of NHS spending in overall government spending rose slightly and its share in GDP was broadly stable.

There were various reforms to the welfare system but there was no fundamental weakening of the welfare state. In 1990, the share of welfare spending in total government spending was broadly the same as it had been in 1980.

Similarly, there was no major reform of the education system, nor any weakening of the power of the teachers’ unions.

The economic facts

How successful was the Thatcher programme? When you look at the bare figures for the growth of GDP per capita, there is no sign of a transformation in the UK’s economic performance, as Tables 1 and 2 make clear. In the period from 1979 to 1990, the average annual increase in GDP per capita was 2.4%. This was well below the 2.8% recorded in the 1950s and ‘60s. It was even below the 2.9% recorded over the supposedly disastrous 1970s. (Mind you, this decade average is flattered by strong growth in the early years. The figure for the disturbed period 1973-1979 was much lower.)

This makes a marked contrast with most of the other countries in this eight country study. For these others, some spectacular growth figures were registered in the period of transformation. In the UK’s case, it is only in comparison with other countries that the achievement of the Thatcher government becomes apparent. Whereas before the Thatcher years, GDP per capita was growing much more slowly in the UK than in France, Germany and the US, during the Thatcher years its growth was above the equivalent in France and the US, and even marginally above Germany. (See Table 2.)

The change in the UK’s relative performance was even starker in relation to manufacturing where, in the years 1979 to 1995, labour productivity per hour worked rose much faster than in France and Germany. By contrast, in the two decades before then, it had increased by much less. (See Table 3.)

On many of the subsidiary indicators of economic success and wellbeing, there were also real signs of progress. Although the UK’s share of international trade did not pick up, the previous steep decline was at least arrested. (See Chart 6.)

The working population increased significantly, both absolutely and as a share of the total population, although both have subsequently risen far higher. (See Charts 7 & 8.) Nevertheless, unemployment remained high even after the strong economic recovery of the mid to late 1980s. (See Chart 3.)

By the end of Mrs Thatcher’s tenure, fixed investment (GFCF) was running at close to a post-war high of almost 25% of GDP, but in the subsequent post-Thatcher period under premiers Major and Blair, it fell back sharply to levels below where it had been in the 1970s. (See Chart 9.)

Inflation was reduced but it never reached the low levels that became normal later and by the end of the Thatcher years it was rising again. In the later stages of the Thatcher/Lawson boom, the economy was in the throes of a strong, cyclical expansion. CPI inflation peaked at over 8% in October 1990.

The average inflation rate for the Thatcher years, at 8% on the RPI and 6.8% on the CPI, was not spectacularly low. Mrs Thatcher managed to overcome many of the inflationary forces of the 1970s but really low inflation, i.e. about 2%, only came about under a Labour Government. (Refer back to Chart 1.)

After initially rising in 1979-81, the ratio of tax receipts to GDP subsequently fell. But the scale of the achievements in this regard was distinctly limited. By the time that Mrs Thatcher left office in 1990, the ratio of government revenue (mainly tax receipts) to GDP was standing at 34%, compared to 38% when she took office. 4This refers to the OBR’s “Public Sector Current Receipts” definition. On another OBR definition, “National Account taxes”, the figures are slightly lower but the overall picture is very similar. (See Chart 4.) This was a meaningful drop but it did not transform Britain into a low tax country. And subsequently, after falling a bit further, the ratio settled at 37%, before the recent rise to above 40%.

These limited reductions in the tax burden mirrored developments with regard to government spending. Chart 5 shows the share of government spending in GDP on the Total Managed Expenditure definition. It fell from a peak of 43.2% in 1982/3 to 34.6% in 1988/9. On the chart, this reduction looks pretty impressive but that is because the vertical axis, against which expenditure is measured, does not start at zero. Moreover, the readings at the end of the 1980s were distorted by the fact that the economy was roaring away at this point. In any case, just before the GFC began in 2007, the share of government spending in GDP was back to 40%.

The budget deficit was brought down and indeed the budget was briefly in surplus at the end of the 1980s. But the budget balance quickly turned into a large deficit with the onset of recession. (See Chart 10.) The ratio of government debt to GDP also fell significantly, before rising pretty much continuously after 1990. (See Chart 11.)

Four other key features of economic performance over the Thatcher years need to be noted. The first is the relentless fall in the share of GDP accounted for by manufacturing. This fell from about 23% in 1979 to about 19% in 1990. It has subsequently fallen further to about 9%. (See Chart 12.)

This sharp fall was significant for several reasons, including the regional imbalance of the economy, but especially because of its effects on the possibilities for productivity growth. In nearly all economies, productivity grows faster in manufacturing than in other sectors.

Mind you, the declining importance of manufacturing was far from being a uniquely British phenomenon. France experienced a similar decline. Germany is the major outlier here. Even there, the share of GDP accounted for by manufacturing has fallen considerably but it remains far higher than the equivalent in the UK and France.

The second key feature is the dominance of consumers’ expenditure in the boom of the late 1980s, with much of it debt-financed and associated with a sharp fall in the personal savings ratio.

The third is connected with this - the weakness of the current account of the balance of payments. After an initial spike caused by North Sea oil revenues – and government receipts from the North Sea reached a peak of 3% of GDP in 1984/5 - the current account balance deteriorated to a deficit of about 4% of GDP in 1989. (See Chart 13.)

The fourth feature is that, despite several redefinitions aimed at disguising its true extent, unemployment remained high throughout the Thatcher years. As Russell Jones puts it: “ However it was measured, the jobless rate was higher in its best year in the 1980s than it was during its worst year of the 1970s.”5Jones, The Tyranny of Nostalgia, p 59.

Success in the political after-life

1990 and 1991 may have been difficult years for the economy but after the UK left the ERM in September 1992, economic performance revived. For the years 1991 to 1997, the UK’s average annual growth rate of GDP per capita was 1.8%, again nothing spectacular but higher than the rate in France Germany and the US. (See Table 2.)

Admittedly, this growth performance was boosted by the benefit of the lower exchange rate made possible by the ERM exit, but this does not undermine the point abut supply side performance. After all, the point is that the economy was able to benefit from the lower exchange rate rather than losing all of its initial benefits in a burst of inflation, as has happened on some other occasions.

Moreover, the improved economic performance continued under the following Labour Government which largely accepted the Thatcher settlement on trade union laws, privatisation, fiscal policy and taxation. Indeed, this “New Labour” Government saw the fulfilment of Mrs Thatcher’s reforms. During the period from 1998, the year after Labour took power, to 2007, the onset of the GFC, GDP per capita grew at an average rate of about 2.2% per annum, faster than the rates in France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States. (See Table 2.)

Nor can this performance be explained by changes in workforce participation, as Table 4 makes clear. The UK’s relative performance was similarly good when measured on output per employed person. And on the growth rate of GDP per hour worked, shown in Tables 5 and 6, the UK also generally did well until 2007. (Table 5 shows the growth of real GDP per hour worked, broken down into decade averages, whereas Chart 6 shows the same data but broken into sub-periods that align with political changes and the onset of the financial crisis in 2007.)

The distinguished economic historian, the late Professor Nick Crafts, noted that by 2007, the UK had a slightly higher GDP per capita than either France or the former West Germany. Admittedly, labour productivity per hour worked was still lower in the UK. But it made up for this through longer working hours and higher rates of employment. These factors were themselves very much the result of the reforms of the Thatcher period.6Nicholas Crafts, “The Economic Legacy of Mrs Thatcher”, Voxeu, 8 April 2013.

It looked as though the UK had indeed turned a corner and was now gaining ground against other leading countries. Unfortunately, as Tables 2, 4 and 6 make clear, the UK’s outperformance came to an end with the GFC. After that, the UK’s growth in per capita GDP fell back to only 0.5%, the same as France, but well below the rates recorded in Germany and the US.

An overall assessment

What are we to make of the Thatcher years? Was there a real economic transformation? The first couple of years of the Thatcher period were a macroeconomic disaster. Many apologists will say that imposing such pain on the economy was the only way of bringing about the transformation that Mrs Thatcher desired and the country needed.

They may be correct that the economy needed some strong medicine but we are sceptical that the type and intensity of the treatment were well-chosen. And the medicine very nearly killed the patient. It is striking and surely telling that the policy on inflation reduction was based on a critical misunderstanding. Key ministers, including the chancellor and Mrs Thatcher herself, believed that controlling the money supply would bring inflation down ineluctably – and perhaps painlessly. A Medium-Term Financial Strategy was constructed, laying down target rates of increase of the money supply and levels of public borrowing in the years ahead.

In the event, inflation fell despite the money supply continuing to grow rapidly. It was economic recession and unemployment, brought on by high interest rates and the associated strong pound, that brought inflation down in time-honoured fashion. In subsequent years, red claw monetarism was gradually (and quietly) abandoned.

In the disinflationary process, the exchange rate of the pound played a key role. It was allowed, and even encouraged, to soar to extreme heights. During the two years after the first quarter of 1979, the pound rose by about 25%. Meanwhile, the UK’s domestic labour costs were rising about twice as fast as the equivalent in our competitors. This had devastating effects on the competitiveness of British industry and was itself responsible for a large part of the deindustrialisation that followed.

Apologists might say that the strong pound was not only due to Mrs Thatcher’s monetary policies but also to the advent of North Sea Oil. For a time, sterling was seen as a petro-currency. This is true but this does not really exonerate the government because surely what it should have done was to have used the revenues from North Sea Oil to build up overseas assets by selling sterling on the exchanges. This would have moderated the strength of the pound and provided a useful rainy day fund. As a share of GDP, gross oil production rose from zero in 1974 to 2.7% in 1979, the year Mrs Thatcher took power, and 7.4% by 1984.7C. Bean, “The Impact of North Sea oil” in Rudiger Dornbusch & Richard Layard, The Performance of the British Economy, Oxford, 1987.

Instead, the revenues from oil taxes disappeared into the general public finances and, because of the adverse macroeconomic effects of the strong pound and tight policy, much of the benefit was lost in the need to pay increased amounts in unemployment benefits. (There is a marked contrast here with Norway, which used its North Sea revenues to build up a huge sovereign wealth fund.)

We believe that the government’s macro policy in the early Thatcher years was a mistake. Yes, without it, the inflation rate would have come down more slowly but equally, more of Britain’s industrial base would have been saved. The process of weeding out inefficient firms and practices did not have to take place at a speed and intensity dictated by the balance of opinion among international portfolio holders on the desirability of holding sterling.

Perhaps the clearest evidence that this policy was bizarre is the fact that within ten years the Treasury was attempting to steer the economy by reference to the exchange rate, firstly by surreptitiously shadowing the Deutschmark, and then by openly joining the ERM. It is difficult to believe that both the earlier complete indifference to the exchange rate and the later obsession with it were right.

Moreover, this macro policy almost destroyed the whole Thatcher experiment. As argued here, the transformatory effects of Thatcherism on the economy derived from various micro reforms which only began in earnest in 1983. Yet pushing through these reforms and being able to sustain them in a democratic country like the UK in the end depended to a considerable degree upon an accident of history.

Despite the very weak leadership of the Labour Party, without the Falklands victory, the Conservatives might well have lost the 1983 election. In that case, whether under a Labour Government or the SDP, or some coalition, economic policy would surely have been different. The legacy of Mrs Thatcher would have been a devastated economy with next to no reform accomplished.

Admittedly, some good judges believe that this exaggerates the importance of the Falklands victory and contend that the Government’s popularity was starting to recover before the war. Yet, even if the Conservatives would have been able to win an election without the Falklands factor, their majority would surely have been nowhere near as large as the one which actually materialised in 1983, and it would have been more difficult for Mrs Thatcher to be as radical as she turned out to be.

Interestingly, macro policy also went off the rails at the end of Mrs Thatcher’s tenure, with the economy roaring away and inflation rising, setting up the need for much tighter policy which duly sent the economy into another serious recession. So these Conservative governments led by Mrs Thatcher presided over two serious recessions in the space of not much more than a decade, both associated with gross errors of macro/monetary policy.

There were two other major areas of failure, this time in the micro sphere. First, the Thatcher government presided over, and arguably worsened, serious distortions in the housing market. It is paradoxical that whereas millions of British home-owners have regarded the housing market as a wonderful feature of the economy and the bedrock of their own financial security, in regard to its effects on the economy, in fact it has been a serious failure. 8For an excoriating assessment of this failing see John Muellbauer and David Soskice, “The Thatcher Legacy: lessons for the future of the UK economy”, The Resolution Foundation and the LSE, November 2022.

Second, for all the benefits that it brought, as noted below, the rapid growth of the financial services sector unbalanced the economy and laid the groundwork for the UK’s acute vulnerability in the global financial crisis of 2007/9, from which the country has never fully recovered.

Yet there were some highly positive things about the Thatcher governments, mainly in the micro sphere:

- Astonishing boldness, with the chancellor, Sir Geoffrey Howe, in his first budget, cutting the top rate of tax from 83% to 60%, increasing VAT from 8% to 15% and abolishing exchange controls;

- More radical tax cuts, tax reform and simplification of the tax system under chancellor Lawson;

- Resilience and determination, with the course of policy adhered to despite widespread and intense opposition and in the face of weak economic performance;

- Fundamental changes in labour relations with huge reductions in union power and a large drop in the number of days lost to strikes;

- A fundamental re-structuring of the ownership of the economy through the privatisation programme that transformed the post-war settlement;

- An intensification of competition which pressurised management into improving performance9See Nicholas Crafts “British Relative Economic Decline Revisited: The Role of Competition”, Explorations in Economic History, Volume 49, 2012.;

- Huge inflows of FDI which strengthened UK economic performance;

- The stimulation of entrepreneurship and venture capital which gave a spur to the development of new industries such as biotech;

- The revival of the City of London to the point where it became the largest international financial centre in the world for the first time since 1914.

Answers to the key questions

In the introduction to this study, we posed several key questions, the answers to which we hoped to find in our investigations. For the UK in the Thatcher period, these are our answers:

Was there a plan?

There was no pre-envisaged plan as such for economic revival but there was a vision and a strategy. The conquest of inflation and the stabilisation of the public finances came first. Interestingly, there was an explicit plan for this in the shape of the Medium-Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) which laid down target rates of growth of the money supply and for the level of public borrowing.

There was no explicit strategy for tax rates but the ambition was clearly to bring the overall rate of taxation down, to eradicate high marginal rates and to simplify the system. These changes were themselves supposed to bring increased efficiency Over and above the effect of these changes, the hope for growth rested on a reduction in trade union power, privatisation and an intensification of competition, as with the “Big Bang” in the City in 1986.

How long did it take for improvement to be clear?

A radical improvement in the UK economy was not evident for a few years after the reform programme began. Inflation initially rose, peaking in Q2 1980 about a year after Mrs Thatcher’s election victory in 1979, although by 1981 it had fallen back considerably. The economy started to recover in Q2 1981, But the perception that there was a “revolution” in economic performance did not gain hold until after 1983. The “Lawson boom” occurred after the 1988 budget. Unemployment continued to rise well after the economic recovery began. It peaked at 11.9% in Q2 1984, about five years after Mrs Thatcher’s election victory in 1979. Thereafter it fell rapidly but it was still extremely high when Mrs Thatcher left office.

Were there losers? And how was support for reform sustained?

Mrs Thatcher’s economic reforms created many losers. Prime among them were all those who lost their jobs, especially in manufacturing in the recession of 1979-81 and in the restructuring and the wave of privatisations that followed. Moreover, because of the concentration of manufacturing in particular areas, many towns, cities and regions were effectively losers from the Thatcher programme.

Mrs Thatcher nevertheless retained adequate support because she carefully and gradually sidelined major figures within her own party who opposed her policy and because the external political opposition was weak and divided. There was also a reservoir of support from the widespread feeling that things could not go on as they had been in the 1970s and that change was bound to be painful. Success in the Falklands War of 1982 undoubtedly helped and may well have been vital. Soon after that victory, the clear signs of economic improvement helped to strengthen her position.

Did the transformation involve a radical restructuring?

The Thatcher transformation most certainly did occur through a radical restructuring of the economy, most notably through the privatisation programme. But the improvements to be expected from weaker unions, lower inflation, lower and better structured taxes and a more competitive regime affected just about all parts of the economy and therefore some improvement could be expected even in activities and sectors that were not restructured.

Was there a sequencing of reforms and was this ideal?

The radicalism of the Thatcher government started straightaway but there wasn’t an attempt to do everything at once. It was probably correct to put the conquest of inflation and the stabilisation of the public finances first. And it was surely correct to delay some of the more radical measures until after support for the government had strengthened, as it did after 1982.

Did the transformation involve much higher savings ratios by households and/or the whole economy?

The Thatcher transformation did not occur as the result of a radically higher savings and/or squeezed consumption. The personal savings ratio remained low throughout the period. Moreover, an improved fiscal position was not enough to stop a radical deterioration in the current account of the balance of payments.

Was the transformation the work of one key person?

It is impossible to imagine the Thatcher transformation without Mrs Thatcher. That said, this was no one woman band. She worked closely with a group of senior ministers who were fully bought in to the approach. She could not have achieved what she did without them.

Acknowledging the unmeasurable

There was something else that was extremely important. Although economic historians who confine themselves to the statistics may miss this effect, anyone who lived through those years will know better: Mrs Thatcher changed the zeitgeist.

Under her leadership, it became desirable, even cool, to work hard and to aspire to succeed. For good or ill – and plenty of people thought, and still do think, that the apparent elevation of the importance of individual economic advancement and the apparent denigration of “community” were distinctly ill – Mrs Thatcher and her leading ministers changed the economic climate in this country. So much so, that they even managed to change the Labour Party. You cannot get much more radical than that.