Authors

Content

Industrial Policy in an Age of Global Economic Uncertainty

This paper is the second in Policy Exchange’s new programme to shape the UK’s approach to Industrial Policy in an era of Global Economic Uncertainty.

Bringing together strands of thinking from economics, trade, energy, foreign policy and defence, the programme explores how Britain can not just survive, but thrive, in a new, more tempestuous, international order.

In a global economic environment increasingly buffeted by major economic shocks, how can the UK chart a successful economic and industrial policy? How does a commitment to free trade respond to the increase in protectionism from the United States, shaped by the twin drivers of domestic political imperatives and national security concerns? How do the economic imperatives of industrial policy interlock with security considerations, exemplified by the challenges faced by the western industrial base in supplying sufficient munitions to Ukraine? How can we position the UK to maximise the opportunities – and minimise the challenges – of the vital transition to Net Zero? How do new threats to national security, such as cyber and AI, impact the economic calculus? How can we be ready to weather repeated commodity price shocks? And what role, if any, should Government play as companies adapt to a new understanding of the fragility of global supply chains, acutely conscious of the stresses that geopolitical events can place on the global economy?

Policy Exchange believes free markets, competition and free trade remain at the heart of any route to prosperity. The question is how should the UK respond in a world where these values are less widely held, or where security, environmental or domestic political imperatives may give rise to priorities and policies that conflict with these? How to maintain and develop an industrial base that meets the needs of both economic prosperity and national security? How best to ensure the UK’s competitiveness in an increasingly uncertain world? How to increase our sluggish productivity – and get growth back on the right track? And how can we develop a clear framework that can allow decisions on competition issues, subsidies or trade to be taken on a transparent, objective and rational basis?

Papers in the series include:

- The Future of the UK Auto Industry (June 2023) – Sir Geoffrey Owen

- Delivering on the Atlantic Declaration (June 2023) – Alex Simakov and Iain Mansfield

Executive Summary

At a White House press conference on June 9th, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and President Joe Biden announced the Atlantic Declaration: A Framework for a Twenty-First Century U.S.-UK Economic Partnership.1Policy paper, The Atlantic Declaration. 8 June 2023: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-atlantic-declaration/the-atlantic-declaration The agreement reflects the continued evolution of the Special Relationship, reflecting tremendous pressures that have shaken international economic relations over the past years. If the Atlantic Charter of 1941 represented the dawn of globalisation, the Declaration hearkens to stormier times, in which the underpinning architecture of the global economy is being called into question.

The agreement is intended to reduce barriers to bilateral trade and cooperation across a swathe of sectors, including AI, data, defence, and pharmacology and biological security. However, its greatest impact is a closer partnership on clean technology and energy security; the defining economic issues of our time. In particular, it initiates negotiations to include components with British-produced critical minerals as eligible for American EV tax credits.

That the Declaration falls short of the full Free-Trade Agreement (FTA) contained in the Conservative’s 2019 electoral platform is very much a reflection of the evolving policy landscape. The pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s growing control over the commanding heights of the world economy have delivered devastating blows to the assumption that the world’s commercial and industrial systems must becomes relentlessly more interconnected.

The United States has again embarked upon the construction of a new vision for its economic future, one defined by a greater focus on security, green economic growth, and re-industrialisation. The EU is following suit. Responding to the risk that it will be left out in the cold, the Atlantic Declaration is the United Kingdom’s vital first step to ensuring that the United States continues to seeing us as a valued economic partner.

The principal legislative vehicle to deliver upon America’s ambition is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the cornerstone of a trillion dollar program to reorient the nation’s commercial and diplomatic trajectory, and ultimately to rally her allies in confronting the predation of the global trading system by revanchist powers. Other laws, notably the CHIPS and Science Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, support the same objective.

In this report, Policy Exchange delves into the impetus and objectives of the IRA, considers its consequences for the global economy, and reflects upon those lessons for Westminster as we aim to deliver on the Atlantic Declaration and develop our own green industrial strategy for the coming age of global uncertainty. The paper focuses upon the international implications of the IRA and how the UK can work internationally to support new climate alliances, integrate supply chains with allies and secure critical minerals essential for the Net Zero transition. The domestic response to IRA must be broad, multi-faceted and integrated within the UK’s wider green industrial strategy – and beyond the scope of this paper.

Next chapterThe Impact of IRA

In just ten months since the Inflation Reduction Act’s passage, the legislation has helped catalyse over $100bn of investment into clean tech and advanced technology manufacturing across the United States – a 10-fold increase in capital investment from 2019.2FT: ‘Transformational change’: Biden’s industrial policy begins to bear fruit, 16 April 2023 That year, there were four industrial projects announced worth at least $1bn. Since the introduction of the IRA, and the accompanying CHIPS & Science Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, at least 33 projects of that scale have been announced.

Even before these new facilities have fully come online, the country’s manufacturing production increased by 2.8 per cent last year – compared to a 2.7 per cent decline in the UK.3Office for National Statistics, March 2023 America’s new industrial strategy is being stimulated by the following incentives of the IRA:4Congress.gov: H.R.5376 – Inflation Reduction Act. Accessed at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

| Principal types of support under IRA |

|

After an initial wave of indignation at the protectionist measures embedded throughout, the European Union has since embraced the ideological pivot, culminating in the Green Deal Industrial Plan and grand commitments on re-industrialisation and economic independence from their leading statesmen.5Emmanuel Macron, FT, Europe needs more factories and fewer dependencies. 12 May 2023 After three generations of broad commitment to free-trade orthodoxy, the Western world is re-assessing the foundation of its economic and commercial relations – including a greater comfort with interventionism and protectionist measures.

Two primary factors have driven the reaction. A growing appreciation that the climate transition presents a major opportunity to revive former manufacturing hubs and other economically distressed communities. And most urgently, that the People’s Republic of China is seizing control over the choke points of the net zero future, posing an existential threat to the economic sovereignty of democratic nations. The shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have raised awareness in governments and boardrooms of the far-reaching economic implications of even a minor clash in the Straits of Taiwan.

Particularly acute is Beijing’s domination over critical minerals and rare earth metal supply chains, including elements like lithium, cobalt, and graphite that are essential for the manufacture of electric batteries, wind turbines and solar panels, few of which can be produced today without passing through Chinese-owned or operating processing facilities. Left unchecked, this near-monopoly would grant the Chinese Communist Party a geopolitical leverage comparable to that of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in the 1970s.

Next chapterThe challenge for the UK

These upheavals present a major challenge for the United Kingdom. The trillion dollars of incentives for domesticating clean tech investment unleashed by Washington and Brussels – and long deployed by Beijing – urgently requires a response from Westminster. After a decade of oscillating over the purpose and legitimacy of ‘industrial policy’, the nation’s economic growth and future prosperity now depends on implementing an effective green industrial strategy – regardless of whether it is called such – of our own.

To date, the British Government has stressed its historic success on decarbonisation, and articulated aspirations for a “pro-growth regulatory regime” combined with public investment towards ‘industries of the future’, to be outlined in the Autumn Statement later this year. However, the Chancellor has rightly emphasised his opposition to a ‘distortive subsidy race’ or protectionist impulses, stressing that “our approach will be different – and better.

Our report, “Delivering the Atlantic Declaration: Adversarial Trade, the Inflation Reduction Act & Britain’s Quest for a Green Industrial Strategy” argues that while the envisioned economic reforms, tax incentives and strategic investments are absolutely essential to improving our competitiveness, they are not enough to match the scale of the challenge we are facing. The UK risks arming herself with a 1990s policy toolkit to fight a 2020s geopolitical contest. A broad-based effort to built green alliances with like-minded nations is essential.

The political momentum away from unrestricted trading relations enjoys deep, multipartisan, and growing support in Europe and America. It is an ideology exhumed by a Republican President’s brand of ‘Make America Great Again’, and now practised by his Democratic successor. Under these conditions, we cannot afford to place all of our eggs into the increasingly beleaguered basket of the World Trade Organisation. While continuing to champion and strengthen the free trade regime, we must concurrently nurture a new ‘Green Trade’ alliance amongst our allies and at the expense of China and other adversarial powers.

Failure to find plurilateral alignment on defensive trading measures may instead see the return of 1930’s style protectionist fragmentation at great cost to national prosperity and the journey to decarbonisation. By opening negotiations on British critical minerals’ eligibility for the IRA’s clean vehicle tax credit, the Atlantic Declaration is a major initial step in embracing these new economic realities, but it cannot be our last.

The recommendations contained in this report are no panacea for generations of industrial decline and overseas outsourcing. In almost all futures, China will continue to be a major trading partner, but even a partial decoupling from China, our fifth largest trading partner, will inevitably increase consumer costs and disrupt supply chains, potentially slowing our decarbonisation journey over the immediate near-term. But these risks can be managed, and are unavoidable if the UK is to join our allies in restoring our economic sovereignty.

Alongside the international perspective the UK’s response to IRA – and to the wider question of how to maintain a competitive industrial sector in an increasingly protectionist world transitioning to Net Zero – requires a broad-based domestic response, considering matters from planning to skills to transport – and much more. The tightening fiscal environment of increased public debt and rising interest rates will make what was already a difficult task even more challenging.

How can the UK balance energy security, affordability and the transition to Net Zero? How to support UK industry in the face of subsidies that we cannot match? Which industries can we really be competitive in? And what might the change of government, and the political commitments already made by Labour – from its stance on North Sea Oil and gas to its plans for a new state owned clean energy company – mean for the UK’s green industrial strategy? These, and other related matters, will be addressed in future papers in this series.

Next chapterRecommendations

- Expeditiously reach an agreement over the UK’s inclusion in eligibility for the critical mineral sourcing requirements for the Section 30D clean vehicle tax credit for the IRA. This will be essential to improving prospects for the UK’s automotive sector and demonstrating the substantiveness of the Atlantic Declaration, supporting the recommendations set out in Policy Exchange’s recent paper The Future of the UK Auto Industry.

- Continue negotiations over sourcing requirements to ensure that British critical minerals and critical mineral-derived inputs are eligible for any subsequent supply chain conditionalities. On both sides of the Atlantic, there is a strong prospect for further policies imposing conditions on the origins of critical minerals, whether in eligibility for subsidies and credits, or restrictions in development of sensitive technologies and nationally significant infrastructure projects. The UK and USA must reach an agreement on proactive eligibility for each other’s critical mineral supply chains under all future legislation.

- Adopt a gradually expanding Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) as a first step to incorporate non-financial factors into our trading regime. Investment into the decarbonisation of our power sector has greatly reduced the carbon intensity of our electricity to 260 grams of CO₂e per kWh, but the transition to renewables, fixed costs and the inherent higher cost of gas as compared to coal has imposed significant near-term financial costs, contributing to industrial power prices averaging 15p per kWh. By contrast, China has opted for lower cost but highly-emitting coal-fired generation stations, producing a national average of 544 grams of CO₂e per kWh, priced at approximately 7p per kWh. Imposing a CBAM would charge a tariff on energy and carbon intensive imports, such as steel, from countries like China, thereby helping ‘level the playing’ for cleaner domestic producers and further increase demand for emission reduction investments.

- Develop a systematic Security-Risk Assessment Framework through which to analyse the UK’s resource dependencies and potential vulnerabilities with adversarial trading partners. As signalled in the Declaration, the state must expand its role in managing the national security threats inherent in our economic relations, ensuring incentives for sourcing supply chains domestically or through allies, and imposing limits on unreliable supply chains – particularly for green tech procurements including the hydrogen and CCUS clusters, Small Modular Reactor (SMR) competition, transmission system expansion, and other nationally significant infrastructure projects.

- In collaboration with allies, establish a Strategic Critical Mineral Reserve to improve our industrial resource security. Targeting our most acute supply vulnerabilities, the UK must expand availability of illiquid and monopolistically-produced materials that are essential to our clean technology manufacturing sector over the next 30 years. A commitment to stockpile purchases would reduce risks for new extraction projects, while strategically-timed releases would help mitigate commodity cycle volatility.

- In coordination with allies, develop a mechanism to support the Strategic Critical Mineral Reserve by establishing the state as a buyer-of-last-resort. This could be achieved either through either a floor price for domestic production or a Contracts for Differences (CfD) scheme – either would reduce risk and capital costs for prospective mining ventures in high potential areas, particularly Cornwall, Wales, and Northern Scotland, and metals recycling ventures in industrial clusters across the UK. It is also imperative to establish a systematic recycling regime for our industrial metals to process the retirement of first generation renewable assets. While the UK will continue to have a strong dependency on imported minerals, even a small domestic industry could help to relieve pressure. Such a mechanism could act as an important tool to attract major investment from allies – including the United States – to help grow the domestic supply of minerals.

- Revive negotiations on the Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) and expand initiative to include environmental services – within, or beyond, remit of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Delivering meaningful progress on a multilateral trade agreement covering environmental goods and services through the WTO would help revive the organisation and establish a rules-based framework for the post-IRA geopolitical reality. If progress cannot be achieved under a Most Favoured Nation (MFN) approach, then the UK and our allies must pursue an alternative, plurilateral agreement under the auspices of an independent ‘Climate Club,’ focusing on like-minded nations willing to implement similar CBAM regimes.

The Political Economy behind the IRA

The IRA is an unconventional piece of climate legislation. While the bill is the most impactful environmental action taken by the U.S. Congress since the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the single largest investment in climate action ever made, the primary focus of this bill is not emissions reductions but rather re-industrialisation and labour under a banner of ‘Made-in-America.’ The IRA’s development and mechanisms are also a reflection of America’s intense political partisanship within a frail legislative process, which this section will explore.

Most climate legislation introduced by developed economies since the Kyoto Protocol (1997) has fundamentally aimed to restrict national – or subnational – jurisdictions’ emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs), collectively referred to as carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e). Within the decades-long policy development processes led by academics and NGOs, the heterodox processes for reducing emissions was to adopt a form of either:

- Carbon taxes: whereby levy is imposed on market participants for each tonne of CO2 emitted; or

- Cap-and-trade: also known as emissions trading, whereby an annual limit is imposed on total CO2 emissions, and market participants are required to buy, or trade, an allowance for each tonne emitted

The premise of carbon pricing as being the most efficient means of incentivizing decarbonisation is near-universally supported within the economic profession, having been pioneered by the likes of Milton Freedman and unanimously endorsed by Nobel Prize laureates in Economics; however, it has faced political difficulties in being implemented effectively.

The premise of these policies is that CO2e emissions are a negative externality that imposes costs onto third parties, and by incorporating those costs into commercial transactions we can achieve a fairer and more rational market outcome. Further, carbon taxation is deemed a more effective policy than either subsidies or regulations, as it empowers market participants to determine the most efficient means of reducing their emissions rather than having governments ‘pick winners and losers’ or impose inflexible and manipulatable rules. Starting from an initially low level upon introduction, the price on carbon is meant to gradually increase – whether through a higher tax or a reduction in allowances – to achieve more ambitious emissions reduction targets.

Dozens of states around the world have adopted either carbon prices or cap-and-trade regimes as the linchpins or their climate strategies, including the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) in 2005 and the UK’s separate ETS as of 2021; Canada’s carbon tax introduced in 2019; and over a dozen carbon markets introduced in American states, including California and Washington.

Through varying designs and policy mechanisms, the governing principle of these national climate strategies is to increase the cost – and thereby restrict the total output – of CO2e emissions. This approach provides the overarching target through which all downstream commercial and economic developments are facilitated, from adopting EVs to installing solar panels to decarbonising steel. As national carbon pricing regimes mature and develop familiarity with industry, the clarity of a steadily increasing price signal – especially combined with long-term policy certainty – can create highly favourable conditions to drive large investments in decarbonisation and electrification.

However, in passing the IRA, the US has turned away from emissions reductions and instead adopted a fundamentally different governing principle in approaching the climate transition. The American strategy, described below, re-invents import substitution industrialisation (ISI) for the climate age, targeting a replacement of foreign energy imports with domestic renewables, and displacing clean tech supply chains with Made-in-America alternatives.

In a direct challenge to decades of accelerating globalisation, President Biden’s climate program prioritises revitalisation of America’s traditional manufacturing industries at the expense of trading partners and allies. The ongoing implementation of this strategy is already challenging long-standing norms from international trade policy and geopolitical competition. The weight of the IRA – both in its spending power and its soft power – has a gravitational pull that has changed the world around it, including the WTO.

Within this new world order, there are challenges as well as opportunities for the UK. the IRA introduces Local Content Requirements (LCRs) as eligibility requirements for tax credits and grants, from which the UK is shut out. However, America’s clean tech and critical mineral supply chains are not mature enough to support this level of demand – creating vital opportunities for the UK and other allies to develop closer partnerships in supporting the decarbonisation and re-industrialisation of each others’ economies.

In this section, our report will delve into America’s turbulent political history on climate policy, how the IRA was passed by virtue of being reframed as a re-industrialisation strategy in order to gain bipartisan support, and the consequent integration of America’s economic, industrial, trade, and foreign policies under a protectionist IRA banner.

Next chapterThe Political Road to an America-First Green Industrial Strategy

President Bill Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol but failed to secure Congress’ ratification. Instead, in 1997 the Senate passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution with a vote of 95-0, pre-emptively renouncing any agreements that limited US emissions unless those rules applied equally to developing countries.

The George W. Bush administration widely opposed efforts to restrict domestic emissions while raising doubts as to the scientific consensus on climate change. Under President Obama, the Waxman-Markey Bill (American Clean Energy & Security Act of 2009) would have introduced an EU-style Emissions Trading Scheme which was approved by the House of Representatives, but the inevitability of a Republican filibuster meant it never reached the Senate floor.

Within months of taking office, President Trump repealed domestic climate policies and withdrew from the Paris Agreement. President Biden was elected pledging to take unprecedented action to flight climate change, issuing an executive order reinstating the Paris commitments on his first day in the Oval Office, pledging to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, and has now committed over a trillion dollars of investment through the IRA, Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA) and CHIPS and Science Act.

Two factors defined the possible ambitions of the administration’s climate agenda. Firstly, the Democratic Party enjoyed control of both the House (222-213) and Senate (50-50, with Vice President Harris as tie breaker) at inauguration.6Senators Bernie Sanders and Angus King sit as Independent but are members of the Democratic Caucus However, being short of the 60 seat supermajority required to overcome the filibuster left the budget reconciliation process as the only avenue to pass substantive legislation. The reconciliation process requires a simple majority vote and allows for changes to federal spending, revenue, and the debt limit, but severely limits any attempts to introduce the kinds of regulatory restrictions, emissions standards and other provisions found in conventional climate policies as described above.7https://www.npr.org/2021/09/14/1026519470/what-is-budget-reconciliation-3-5-trillion

Secondly, the President’s razor-thin Senate majority required the support of every single Democratic Senator, representing a wide expanse of centre-left ideology with vastly divergent conceptions of climate justice and the state’s environmental responsibilities, as well as non-climate related spending. The administration faced particularly difficult negotiations with Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

Throughout his efforts to build support for his IRA and related legislation, President Biden has consistently framed his plans for climate action as the forging of an American industrial strategy for the twenty first century, invoking the precedence of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. While emissions reductions and fulfilling commitments under the Paris Agreement created the impetus, it was the opportunity to revitalise domestic manufacturing and improve economic competitiveness with China that gathered his political coalition to success where previous climate efforts had failed.

The Administration embraced myriad compromises from their ideal position to achieve support from all 50 Democrats. Foremost was the preemptive abandonment of any carbon pricing regime – either carbon tax or cap-and-trade – that would have been opposed by several Mid-Western Senators with high concentrations of emission intensive industries, as well as those from fossil fuel producing states, namely Sen. Manchin.

The administration’s first major success on climate-related policy was passage of the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA) in November 2021, including bipartisan support from 13 Republican representatives. The legislation approved $550bn of new spending across conventional infrastructure spending, but also included;

- $7.5bn to build a national EV charging network

- $71bn on environmental remediation and water storage

- $73bn on upgrading clean power infrastructure and transmission

- $106bn on improving rail and public transit systems

The IIJA was meant to accompany the more ambitious and comprehensive climate components of the Build Back Better Act, initially proposing some $3.5 trillion worth of spending on a post-covid recovery programs with a heavy focus on climate investments. Navigating it through the House of Representatives lowered that sum to $2.2tn. Thereafter, negotiations through the first weeks 2022 with Sen. Manchin collapsed on his opposition to the price tag and impact to federal debt impact (primarily related to the child tax credit). Renewed efforts through the spring and summer came to no avail and were publicly abandoned by July.

The administration found some recourse in passing the CHIPS and Science Act on 27 July, the clearest manifestation of America’s new ISI industrial strategy. The legislation provided some $280bn of new funding to support domestic research and attract manufacturing of semiconductors in the US. Development and production of semiconductors is a critical component in controlling advanced technologies, including Electric Vehicles (EVs), batteries and other clean tech assets, as detailed in Policy Exchange’s report in June 2022, Semiconductors in the UK.8https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/semiconductors-in-the-uk/

Framed as a response to China’s growing presence in the sector – and fear that their invasion of industry-leading Taiwan would shatter supply chains – the legislation was passed with strong bipartisan support. Several significant semiconductor manufacturing investments have been announced in the US, including $5bn from Wolfspeed, Inc. in North Carolina, $20bn from Micron Technology in New York, and TSMC expanded their investment in Arizona from $12bn to $40bn.

With opinion polls widely suggesting that Democrats would likely lose control of both the House and Senate at the forthcoming mid-term election in November, the window of opportunity for President Biden to pass any substantive climate program was quickly receding. This growing pressure evidently softened their caucus’ internal negotiating positions, leading Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Manchin to announce their joint sponsoring of the IRA, which was passed by the Senate after a 16 hour voting session on 7 August 2022 (with Vice President Harris casting the tie-breaking ballot).

At $739bn over ten years, the IRA was a reworked, lower-priced version of the original Build Back Better Act, with a number of substantive changes that diminished the focus on emissions reductions and reflected the increased influence of Sen. Manchin, a proud champion for – and beneficiary of – his state of West Virginia’s long-standing coal industry.9https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/15/politics/joe-manchin-coal-financial-interests-climate/index.html The structure and impact of this legislation is detailed below.

Drill Baby Drill

As a further accommodation to maintain their support, the IRA has numerous provisions requiring continued development of America’s thriving oil and gas sector. To the extreme chagrin of environmentalists, the IRA not only reinstated several previously planned auctions for offshore oil and gas drilling, but also imposed a requirement on the Department of the Interior (DOI) to conduct future offshore oil and gas auctions as a precondition to the DOI being permitted to host auctions for offshore wind leases. At his State of the Union address in February, President Biden went off-script from his prepared remarks to acknowledge that, “[W]e’re going to need oil [and gas] for at least another decade, and beyond that.”

The IRA also delivered a generous tax credit for carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) intended for use by oil and gas producers that can be realised for up to twelve years from the investment, against objections from progressives in the Democratic coalition who are opposed to existing fossil fuel development, much less the preeminence of new projects. There’s also $1.55bn to support these companies in reducing methane leakage, available for both existing and future projects. While studies suggest the IRA offers the opportunity to reduce nationwide emissions by an additional 7% to 9% by 2030, and the emissions intensity of oil and gas development will decrease, it is entirely possible for total emissions from extraction and processing of fossil fuels to increase through that period.

Any lingering illusions that President Biden would thereafter adhere to his campaign promise of banning new fossil fuel projects on federal lands were put to rest by his administration’s recent granting of approval for ConocoPhillips’s Willow project in the permafrost of the Alaska North Slope.10https://apnews.com/article/oil-climate-biden-alaska-willow-conocophillips-26d8195fec58bb0469ddf46df60a020a If completed, their investment would see 150 wells producing a peak of up to 200,000 barrels of oil per day – some 1.6% of America’s current production – over 30 years, creating some 2,800 jobs and $17bn of tax revenue. Combusting that petroleum output will also release 280m tons of CO2 emissions, the equivalent of Spain’s annual carbon footprint, and a major blow to climate activists around the world.

Made-in-America

As a conception of America’s economic future, the legislation is more strongly aligned with an America-First set of values that is more closely associated with Donald Trump than Democrats would care to admit.

Since the 1970’s, America embraced an increasingly interconnected economic world order that concentrated the higher value-added functions domestically while outsourcing the lower value-added functions to trading partners with lower labour and input costs. Initially starting with textiles and other unskilled or lower-skilled labour, American corporations increasingly pursued profit-maximisation by retaining only the most specialised activities like innovation, design, finance, and managerial functions, while off-shoring most of the supply chain, including materials processing and manufacturing. Employment in the latter peaked in 1979 at 19.6 million jobs, and has fallen to under 13 million at present – during which time the total American population increased by over 100 million.

Efforts to repair – or exploit – the social ailments caused by this economic dislocation have dominated recent generations of American politics. The urgency of adopting an alternative course was heightened by experiences through the covid pandemic, when global supply chain disruptions exposed the paucity of domestic chains as a severe impediment to American operational independence. The inability to produce personal protection equipment, and severe limitations on domestic vaccine manufacturing, delivered a more stirring call to action than decades of Appalachian plight.

Of even greater concern was China’s increasingly apparent supremacy and control over emerging clean tech sectors, the results of a concerted, decades-long green industrial strategy. This is best illustrated by the EV market, and control over the all-important critical mineral supply chains. Over the past thirty years, the Chinese regime committed to long-term, state-led investment in mining projects both domestically and across the Global South, combined with more state-led support for high-pollution and low-margin processing facilities.

To reduce costs and ensure reliable access, many advanced manufacturers were enticed to locate their facilities in close proximity, gradually nurturing comprehensive EV and renewable technology supply chains that concludes with the recycling and repurposing of those minerals. In most respects, China’s global prowess in advanced industry greatly exceeds the standing of the UK and the US at the height of their respective powers:11International Energy Agency, Technology Perspectives. 2023

| Global share of production; | Europe | US | China |

| Cathodes | 1% | 1% | 80% |

| Anodes | 0% | 1% | 89% |

| Li-On Battery Cells | 7% | 7% | 79% |

| Solar Wafers | 1% | 0% | 96% |

| Solar Cells | 1% | 0% | 85% |

| Solar Modules | 3% | 1% | 75% |

| Offshore Wind Tower | 41% | 0% | 53% |

| Offshore Wind Nacelle | 26% | 0% | 74% |

| Offshore Wind Blade | 12% | 0% | 84% |

Much as the CHIPS and Science Act aims to achieve for semiconductors, the IRA lays the foundation for addressing strategic weakness on critical minerals and clean tech manufacturing through a tactical disengagement from global trading partners. The Biden administration wants to encourage American and international industries to locate a large share of their supply chains within the United States with the offer of generous financial incentives, access to which was contingent on satisfying local content and labour requirements.

One prominent example is a tax credit of up to $7,500 made available for households to purchase a new electric vehicle (the Clean Vehicle Tax Credit).12In addition, the market price of the EV is limited to $80,000 for SUVs, vans and pick-ups, or $55,000 for other vehicles. Eligibility is also limited to those with a joint household income of $300,000 or less This can be delivered incrementally, with $3,750 contingent on its final assemblage being undertaken within North America, and up to $3,750 continent on a certain portion of the battery’s critical mineral components are sourced or recycled in either North America or in a country with whom America has a Free-Trade Agreement (FTA). This portion starts at 40% of critical mineral value in 2023, and rises by 10% each year until stabilising at 80% in 2027. Moreover, starting in 2025, eligibility for the tax credit requires that no critical minerals can be sourced from “foreign entities of concern”, intended to reduce imports from China and Russia. As the UK does not have an FTA with the United States, it is on this latter subsidy condition that the Atlantic Declaration is initiating negotiations for British supply chain eligibility.13The USA signed this type of agreement with Japan in March

Notably, existing EV manufacturers have expressed concern that, out of the 72 EVs currently available for sale in the US, 21 models were eligible for the tax credit in 2022, but potentially none of the current models might be in 2025 under the strictest interpretation of the rules, due to the prohibition on inputs from foreign entities of concern. Given the paucity of American critical mineral processing capacity, it is effectively impossible to build an EV with an all-American supply chain.

While many US. and multinational automakers that have entered into long-term partnerships with Chinese battery producers bemoan that none of them could qualify for the tax credit under their preferred supply chains, Sen. Joe Manchin would retort that’s exactly the point. His brand of politics is disinterested in subsidising new cars for middle-class families or reducing emissions, remarking in a debate on the stringency of domestic content requirements that “They almost act like they gotta send $7,500 or a person won’t buy a car. Which is crazy, ludicrous thinking for the federal government.”14https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/09/manchin-raising-hell-inflation-reduction-act-00081918

His support for approving half a trillion dollars of new spending was predicated on that car being produced in America, and that emission reduction contingent on supporting American jobs. The IRA is so generous precisely because it must offer automakers and other titans of global industry a compelling enough incentive to decouple from China and accept the immense expense of building all-American supply chains – in some parts from scratch.

Uncle Sam: All Carrot, No Stick

Of the total $739bn raised by the IRA, some $108bn is directed to healthcare spending through Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies and $238bn to deficit reduction. The outstanding $391bn is committed to the energy security and climate change programming that is the focus of this report, divided across the following categories:

- $128bn for renewables and energy storage

- $37bn for advanced manufacturing

- $36bn for home efficiency upgrades and associated supply chains

- $30bn for nuclear power and associated supply chains

- $27bn for a Green Bank

- $20bn for climate-resilient agriculture

- $13bn for EV incentives

- $3bn for Carbon Capture & Storage

The remainder dedicated a range of ecological regeneration, climate resilience, and just transition programming for rural and disadvantaged communities.

The bulk of these funds are delivered through tax credits ($216bn for corporations, $43bn for consumers), grants ($82bn), and loans ($40bn). This approach provides a clear distinction with the kind of climate programs offered in the UK, for example the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS). The BUS provides residential consumers up to £5,000 for upgrading to a heat pump or other low-carbon alternative, backed by a Treasury allocation of £150m per year for three years, a total of £450m.

Even aside from struggling with poor promotion and public awareness – only a third of its annual allotment has been claimed, equating to 7,600 installations by end of January – the scheme is structurally undermined by the finality of its funding model. Once the £450m has been claimed, the program is concluded and households will expect to pay the full price for heat pump installations, potentially tripling total costs.15https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/34006/documents/187196/default/ Suppliers, installers and vendors throughout Britain’s heat pump supply chain are therefore dissuaded from making long-term investments in skills training and domestic manufacturing as consumer demand for their product is designed to drop precipitously in the near future.

By contrast, while the IRA only offers a $2,000 tax credit for heat pumps – plus up to $1,200 per year for accompanying upgrades (such as insulation) – this tax credit is available to an unlimited number of claimants for at least 10 years. The American heat pump supply chain is thereby able to invest with much greater confidence over a longer time horizon without reservations over funding being exhausting.

This fundamental difference between tax credits and subsidies accounts for much of the divergence in adding up the climate investment components of the IRA, most commonly quoted as $369bn or $391bn, with some analysts estimating that the total could exceed $800bn of “spending” from the Treasury.16The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) cites $374bn 17Credit Suisse, 30 November 2022: US Inflation Reduction Act: A catalyst for climate action The distinction between the UK’s and the US’s philosophy to climate spending is made particularly stark on their respective hydrogen and CCUS strategies.

Westminster has undertaken a centralised, top-down approach of developing “clusters”, whereby first two and then eventually four existing industrial hubs will be decarbonised through investments into hydrogen production, storage and transport in parallel with CCUS infrastructure systems.18Cluster sequencing Phase-2: project shortlist (power CCUS, hydrogen and ICC) – GOV.UK The Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) is in the process of developing new “business models” for these sectors and consulting on a hydrogen levy to fund the initiative, backed by a £249m Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF) and myriad innovation competitions.19Energy Security Bill factsheet: Hydrogen and industrial carbon capture business models – GOV.UK The ambition is to help reach 10 GW of production capacity by 2030, but the initiative can only move at the speed of state, wherein any impediments within Departmental decision making will delay the entire sequence – as inevitable with three Cabinet shuffles in the past six months.

America has taken a simpler approach. There is a similar stream of state-led development for four Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs (H2Hubs) that received $8bn from the IIJA.20Federal Register :: Notice of Request for Information (RFI) on Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Implementation Strategy However, the IRA adds new fuel to the fire by offering a massive production tax credit of up to $3 per kilogram of clean hydrogen, locked into the tax code through to 2032 (Section 45V).21Reaching the full $3 is contingent on satisfying several conditionalities, namely a carbon intensity of under 0.45kg CO2e as well as a series of wage and labour standards. Falling short on any conditions scales down the tax benefit received. Alternatively, developers could choose and investment tax credit of up to 30% of the hydrogen production facility: United States: Tax credits for green hydrogen under the US Inflation Reduction Act 2022 At scale, this will reduce the cost of clean hydrogen production by between a third and up to half in optimal conditions, drastically improving the economics – and lowering the cost of capital – of investing into hydrogen systems.

Critically, unlike in the UK, the tax credit provides prospective developers with sufficient support to initiate major hydrogen projects at their own pace and sign long-term offtake agreements without the lengthy and uncertain process of applications and approvals for cluster participation. Equally importantly, the IRA is already funded for a decade, relieving any anxiety that the UK’s £249m NZHF being exhausted before a new funding stream is established, leaving otherwise viable projects stranded without support.

IRA Impacts

The range and breadth of the IRA’s programming affects almost every subcategory of the clean tech ecosystem. This includes a tax credit of $15/MWh for power generated at a nuclear facility, providing strong support for securing investments into upgrading and modernising these critical non-emitting sources of power generation to improve their flexibility. The rise of intermittent renewables has drastically increased periods of ultra-low or even negative marginal electricity prices, eroding the economics of baseload power providers, but who’s retirement would result in even higher consumer bills – especially during periods without wind and sun, and replaced by natural gas generation.22Baseload power refers to generation assets that are optimised for constant or near-constant operation at full-capacity. The practice of reducing nuclear power output during periods of high renewables generation is called “manoeuvring.”

The range and breadth of the IRA’s programming affects almost every subcategory of the clean tech ecosystem. This includes a tax credit of $15/MWh for power generated at a nuclear facility, providing strong support for securing investments into upgrading and modernising these critical non-emitting sources of power generation to improve their flexibility. The rise of intermittent renewables has drastically increased periods of ultra-low or even negative marginal electricity prices, eroding the economics of baseload power providers, but who’s retirement would result in even higher consumer bills – especially during periods without wind and sun, and replaced by natural gas generation.22Baseload power refers to generation assets that are optimised for constant or near-constant operation at full-capacity. The practice of reducing nuclear power output during periods of high renewables generation is called “manoeuvring.”

Over the coming decades, the goal for many of these assets is to redirect their “surplus” output (i.e., when there is abundant wind and solar generation) to non-electricity generation, such as hydrogen production, desalination, and provision of thermal energy for industrial applications or district heating networks.

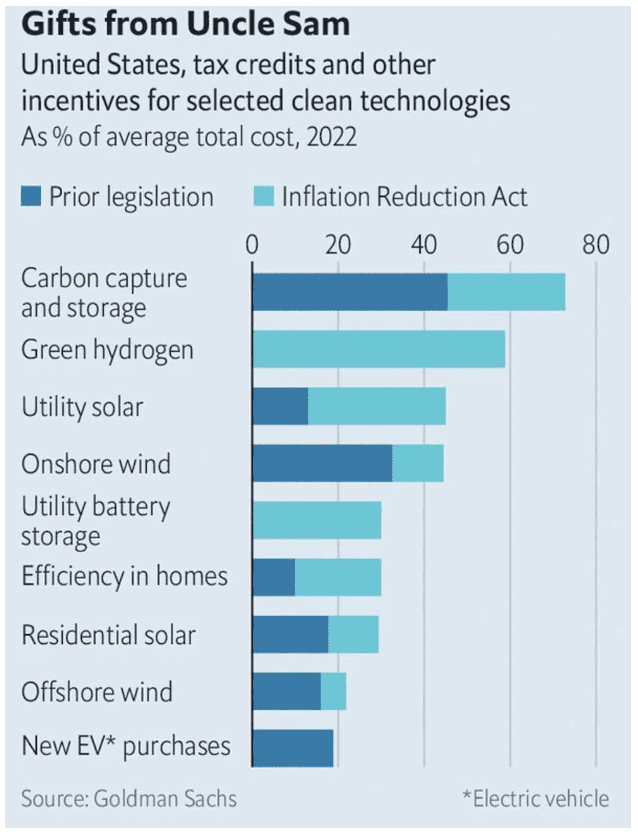

In combination with previously legislated funding, the IRA’s cost reductions and commercial impacts will revolutionise several emerging sectors over the next ten years, as depicted in the figure below. This will have profound implications on the economics of the global climate transition.

On the positive side, increased consumption by American industry will accelerate improvements to the learning curves of nascent technologies like clean hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCUS). This will mirror the rapid improvements to the cost of wind and solar, reducing by over 80% over the past decade, after first movers like Germany and Spain consciously committed to a strategy of early adoption and established reliable demand for global supply chains. Hundreds of billions of dollars of new state-side investment into batteries, smart-grids, and recycling facilities will fuel innovation and breakthroughs that could be replicated with greater certainty – and therefore lower-costs of capital – in the UK.

The near-term challenge is that capital investments contemplated for the UK and other jurisdictions are now pivoting to the USA instead. The prospect of cheaper deployment costs in the medium-term is cause for optimism, but the immediate risk is that Britain’s clean tech supply chains fall irreparably behind, become reliant imports, and no longer be seen as a leading destination for new investment.

Next chapterImplications and Shortcomings of the IRA

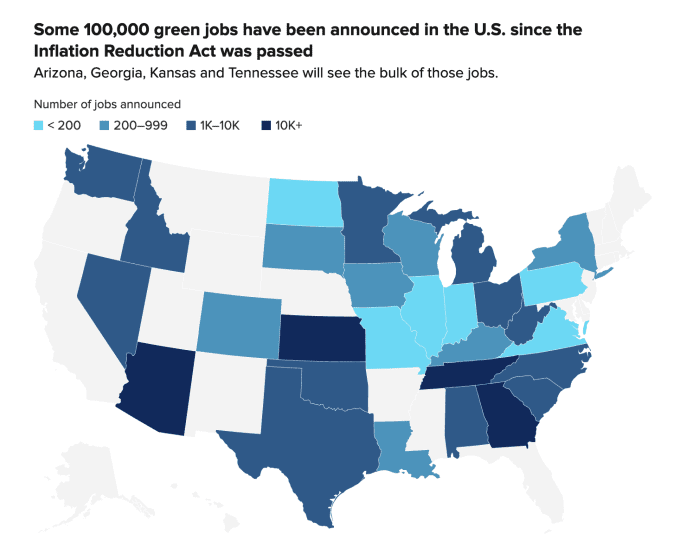

The past six months have seen a tremendous outpouring of announcements for new climate investments across the United States. Companies have announced more than 100,000 clean energy jobs across the country of almost $100bn invested since the IRA was passed into law in August 2022.29https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/us-climate-bill-green-jobs/

For all the applause, there are two significant limitations or shortcomings to the efficacy of the IRA in driving American industrial renewal and scaling a clean tech supply chain. These shortcomings derive from both the design of the legislation itself as well as the country’s broader technical and economic realities; therein lie the opportunities for the UK and other allies to establish themselves as integral partners in America’s climate transition.

The first major shortcoming of the IRA stems – as do so many ailments throughout the western world – from a broken planning system. Much like in the UK, an increasingly archaic, costly, and unpredictable permitting and approvals regime on both the state and federal level has emerged as the greatest hindrance to the deployment of large-scale renewable assets. By 2021, there were over 4,000 applications representing 1,400 GWs of new power generation and storage assets waiting for approval and a grid connection, with hundreds more irretrievably delayed.30For context, this is greater than the entire existing US generating capacity of 1,200 GWs, and would amount to over $2 trillion of investment. However, many of these projects would not necessarily proceed to development even without commercial delays: Record Amounts of Zero-carbon Electricity Generation and Storage Now Seeking Grid Interconnection – Berkeley Lab

In the meantime, the IRA’s benefits – and jobs – are largely accumulating in GOP-run states like Georgia and Tennessee because they tend to have more lax permitting rules, faster regulatory regimes, and lower development costs. The great irony of the IRA is that Democrats are losing out on investments from their own climate program.

The second challenge to the IRA is concerns from America’s global trading partners that the IRA is protectionist and isolationist. These concerns are compounded for trade partners who do not have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the US.

Earlier Congressional attempts to forge a green industrial policy attempted even more isolationist approaches, seeking to restrict incentive eligibility to exclusively American-made products with no foreign inputs. Lobbying from domestic manufacturers – especially automakers – to include North American supply chains built throughout Canada and Mexico since NAFTA (now USMCA) first loosened the stringency. The Biden administration’s determination to sustain America’s global standing by respecting their 18 other FTA partners31America has FTAs with: Australia, Bahrain, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Israel, Jordan, Korea, Mexico, Morocco, Nicaragua, Oman, Panama, Peru, and Singapore. further expanded the benefits – that some of them could be important sources of critical minerals and other primary inputs was another key factor.

Crucially, neither Great Britain nor the European Union have entered into an FTA with the United States, and therefore are excluded from many of the IRA’s more generous financial incentives. The latter’s objection were best summarised through their November submission to the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) consultation, raising objections to nine specific tax credits with local content requirements32The (1) Extension and Modification of credit for Electricity from Certain Renewable Resources Tax Credit, the (2) Extension and Modification of Energy Tax Credit, the (3) Sustainable Aviation Fuel Tax Credit, the (4) Tax Credit for Production of Clean Hydrogen, the (5) Clean Vehicle Tax Credit, (6) the Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit, the (7) Clean Electricity Production Tax Credit, the (8) Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit, and the (9) Clean Fuel Production Tax Credit., expressing that:

“Given their size and design, the financial incentives deployed to meet the United States’ climate objectives unfairly tilt the playing field to the advantage of production and investment in the United States at the expense of the European Union and other trading partners of the United States, potentially resulting in a significant diversion of future investment and production, threatening jobs and economic growth in Europe and elsewhere.

“[…] Furthermore, transatlantic trade, investment and integrated production and supply chains will suffer from disruptions and distortions. The effect of the Act on supply chain resilience and integration (transatlantic and beyond) is particularly worrying. Its intention of nationally reshoring supply and production chains to the United States and decoupling/diverting them from partners like the European Union could lead to negative effects both for the United States and other trading partners. It will contribute to limit sourcing of critical inputs and fuel a harmful competition for inputs at a time when both the US and the EU have committed to closer cooperation on supply chain resilience[.]”

The EU’s letter identifies that the IRA’s domestic content requirements are violations of both the national treatment obligations of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1994) and the prohibition on import substitution subsidies in the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM). They take particular umbrage with the Clean Vehicle Tax Credit, the final assembly requirement for which is similarly in violation of trade-related investment measures (TRIMS).

In simpler terms, the global trading system allows for Governments to introduce subsidies and financial incentives to achieve social and other policy objectives like climate action, but these cannot favour domestic producers to the exclusion of foreign imports. Crucially, while the EU offers a wealth of climate incentives – with a variety of nationally-developed green programs that represent a larger share of their GDP than the IRA does for America – none are so blatantly discriminatory towards imports. For example, Austria offers up to €5,000 for a residential heat pump, irrespective of whether it was manufactured in Salzburg or St. Louis.33When particularly necessary for political purposes, the more civilised approach is to take the extra steps of contriving that local installers only offer a domestically manufactured product, rather than explicitly limiting incentives for foreign versions as done in the IRA

The UK has expressed similar concerns. At Davos, Energy Secretary Grant Shapps described the IRA as “not just anti-competitive, but protectionist,” while Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch remarking that the US;

“[I]s onshoring in a way that could actually create problems with the supply chain for everybody else. And that will not have the impact that it wants to have when it’s looking at the economic challenge that China presents.

So no, I don’t think it’s a good idea, not just because it’s protectionist. But it also creates a single point of failure in a different place, when actually what we want is diversification and strengthening of supply chains across the board.”

The UK and EU’s objections are more than a performative objection in support of the global trading order. With America’s Silicon Valley having established a dominant position in the telecommunications and digital sectors, their European counterparts have patiently nurtured advantageous positions in the renewables, hydrogen and other cleantech sectors, slowly developing the carbon pricing regimes that deliver market signals to incentivise decarbonisation. There is some irony in Europe having spent decades admonishing the United States for lagging on climate action, only to find itself in economic distress over Washington’s belated efforts to catch up.

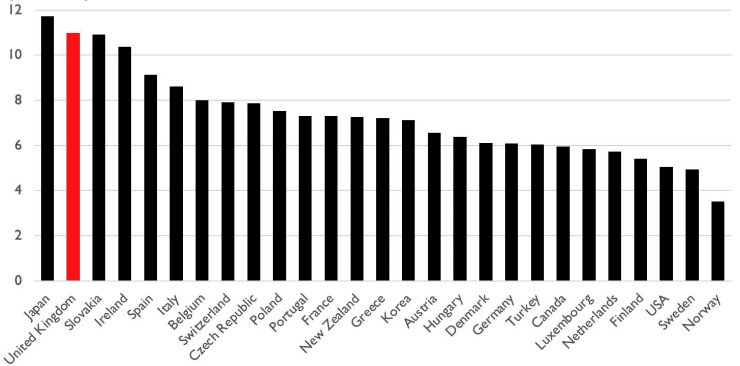

These anxieties predate the IRA. The wholesale price of natural gas and electricity throughout Europe – already consistently higher than those available in the US – began a sustained increase from the start of 2021, and accelerated to multiple times its historic average following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These weaknesses were exacerbated by self-defeating approaches to domestic energy policy, with aggressive restrictions on domestic fossil fuel production and the premature closure of nuclear generating stations.

By contrast, the US embraced the potential of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to unleash a major driver of economic growth, and in 2019 become a net energy exporter for the first time since 1953. With the further advantage of lower corporate taxes, the most energy intensive industrial operators throughout the continent – especially in chemicals, steel and heavy manufacturing – were increasingly looking to the US as their preferred expansion and investment destination. The cost of energy has been a particular challenge for the UK, which the recently announced British Industry Supercharger program may potential relieve:34https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-action-to-supercharge-competitiveness-in-key-british-industries-and-grow-economy

Average pre-tax industrial energy prices over the past five years (pence per KWh)

Source: BEIS, IEA

The IRA poses a further challenge to Europe’s economic interests in the climate transition. Many businesses, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that emerged to supply the EU’s and UK’s adoption of renewables, have since found successful niches in providing those specialised inputs throughout America’s burgeoning cleantech supply chains. The IRA’s LCRs may encourage US developers to replace those providers with domestic suppliers. The larger, longer team challenge is that those European SMEs may elect to protect their market position by opening future facilities in Michigan instead of expanding and exporting from Manchester or Munich, with all of the impact on local jobs and tax revenues that entails.

The EU is taking a multi-faceted approach in responding to the IRA, their Green Deal Industrial Plan, with potentially major consequences for the Union. The scheme would see the EU Commission relax state-aid rules, thereby allowing individual nation-states to tailor subsidies to local content requirements as done by the IRA. Critics are concerned this would advantage larger members with the fiscal capacity to support their domestic industry, at the expense of smaller and poorer neighbours, thereby introducing the kind of protectionism the European project was meant to erase. Either as an alternative or complementary measure, the EU may attempt to raise another green transition fund from general revenues to offer similar tax incentives throughout the Union.

Next chapterThe World Trade Organisation in the Climate Transition

Of all the familiar habits and institutions unsettled by the IRA, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) may face the most challenging future. First incarnated as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) under American leadership in the wave of multilateral institution building that followed World War II – and formally established as a standing body in 1995 – the WTO has served as the foremost guardian of globalisation. The body’s success in reducing average tariff levels from 22% in 1947 to under 5% by the turn of the millennium understates the crucial role it has played in lifting billions of people out of poverty by ensuring the rules around free-trade and enabling export-oriented industrialisation.35Bown, Chad P.; Irwin, Douglas A. (2017). Elsig, Manfred; Hoekman, Bernard; Pauwelyn, Joost (eds.). “The GATT’s Starting Point: Tariff Levels circa 1947”. Assessing the World Trade Organization. Cambridge University Press: 45–74

However, after peaking with China’s accession in 2001, the WTO has struggled in recent years. The latest major initiative, the Doha Development Round, stalled in negotiations over agricultural subsidies and intellectual property rights. In the summer of 2014, negotiations began between 46 members towards an ‘Environmental Goods Agreement’ (EGA) to improve trade rules over renewable generation assets, components, and other clean tech, and ultimately better align the WTO with global climate commitments, with the potential to affect over $1 trillion worth of global trade.

These talks achieved limited progress – even a definition of ‘environmental good’ could not be reached – and collapsed by 2016.36Environmental Goods Agreement: A New Frontier or an Old Stalemate? Few developing countries participated, and the likelihood of achieving their unanimous support for implementation of such a deal – the ‘single undertaking principle’ – was virtually nil. The breaking point was bicycles. China, a highly efficient manufacturer, was determined on their designation as environmental goods for which duties would be eliminated. The EU, advocating on behalf of their smaller and higher-cost set of manufacturers that have thrived behind a 14.6% tariff wall, was resolutely opposed to the measure.37FERDI WP n°287 de Melo, J. & Solleder, J-M. >> Towards An Environmental Goods Agreement Style agenda to improve the regime complex for Climate change, 2022.

Further, the WTO’s integral role in adjudicating trade disputes has been deliberately hampered by the USA. The Obama Administration took the unconventional step of blocking re-appointment of a judge to the all-important Appellate Body in 2011, implying there was a bias against American interests. In his protectionist zeal, President Trump institutionalised a habitual veto – judges’ terms expired without renewal or replacement and by 2018 the body lost quorum to try cases.

Hopes that the election of President Biden would mean a return to normal were misplaced; the pattern of vetos and broader withdrawal from multilateral obligations has largely continued. Efforts by other WTO members to develop an alternate ‘Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement’ have faltered.

US Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai has expressed more positive rhetoric towards overcoming the impasse, but hasn’t offered or meaningfully pursued any proposals for a resolution. Senior Republican Senators have voiced their support for the retrenchment.38Rubio, Cotton, Colleagues Oppose Efforts to Reassemble WTO Dispute Settlement Body – Press Releases This bi-partisan evolution has seen the centre of gravity in American trade policy shift from the USTR towards the Commerce Department; from an organisation dedicated to minimising constraints on cross-border flows of goods and investment to an agency committed to advancing the interests of American companies.39Why the U.S. Trade Office No Longer Runs Trade | Council on Foreign Relations

The roots of this evolution are found in the overwhelming and unresolved frustration towards the WTO’s inability to confront – much less resolve – the systematic abuse and exploitation of free trade rules by China. As remarked by Hugo Paemen, the EU’s former Ambassador to the US, “The world was very happy when China came to the WTO because most people thought China was going to change, but it’s China that changed the WTO.” Even where the WTO has taken decisive action against Chinese market manipulation, as in the 2015 case on rare earth metal quotas described in the next section of this report, the outcome was deemed a failure by western countries.

Passage of the IRA is the next, major step in America’s ideological decoupling. While some politically sensitive sectors like farming and maritime shipping have always enjoyed special ‘accommodation’ within America’s broader commitment to free-trade, the LCRs, preferences for domestic suppliers, and restrictions on sourcing input from economic adversaries are deliberately unaligned with the most-favoured-nation (MFN) principle that underpins the WTO. Even under a functional Appellate Body, Washington has little anxiety over the prospect of the WTO’s retaliatory measures, such as countervailing duties from aggrieved trading partners. The Biden Administration has stressed they “make no apologies for the fact that American taxpayer dollars ought to go to American investments and American jobs” and stressed their expectations that the EU and others should pursue similar industrial strategies, regardless of consistency with WTO rules.40US makes ‘no apologies’ for prioritising American jobs, clean energy tsar tells EU | Financial Times

In the meantime, political momentum has swung towards regional trade agreements that can offer greater flexibility and focus, like the EU and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

In trade policies where the US and EU are cooperating, they are doing so outside the mandate and blessings of the WTO, a prominent example being their negotiations over new rules concerning the carbon intensity of steel and aluminium products that have escalated to a ‘concept paper’ being formally submitted in December.41US Proposes Global Green Steel Club That Would Put Tariffs on China – The New York Times The Administration envisions the creation of an international consortium – a ‘Climate Club’ – that would offer advantages to producers and consumers of metals with low embodied carbon (such as those made in the USA or EU using Electric Arc Furnaces) while imposing tariffs or other disadvantages on metals with higher carbon intensity (such as those manufactured in China with coal-fired generation). The establishment of this consortium would be a major step towards realising the ultimate goal of America’s new green industrial strategy; leveraging climate objectives to drive domestic economic renewal – and it is essential for the UK’s future prosperity that it is part of any such club.

The original – and still acting – agreement from 1947 does offer members exemptions to its rules for environmental purposes, namely Articles 20(b) and (g), which allows for free-trade inconsistent measures if necessary to “protect human, animal, or plant life” or “relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources.”42The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947) However, this allowance is clearly insufficiently flexible to achieve the green industrial strategies that are supported with overwhelming democratic mandates. While the WTO has triumphed over numerous populist waves in the past, the current, post-Great Recession hostility towards multilateralism has combined with existential angst over the global climate crisis. As both forces continue to accumulate influence over democratic societies and their policy makers, the WTO must either submit itself to evolution in both function and ideology, or brace for insurrection.

The UK must embrace a leading role in the body’s transformation. Great Britain is the founder, and foremost beneficiary, of open global markets. Just as we have much to lose from the rise of unbridled protectionism, there is much to gain from the emergence of a new global trading regime that more effectively values the climate commitments into which our nation has made such significant investments.

The triumph of an economic framework for one generation does not mean it should be frozen in time by the next. The same Gold Standard that ushered prosperity for the Victorians spread poverty after the First World War. The merits of competition and comparative advantages are timeless, and in a world in which our principal allies are tilting away from this, we should seek to secure as many of their benefits as we can through a new trading regime that encourages environmental protection and is more effective at preventing exploitation by free-riders and cheaters.

A successful revival of the Environmental Goods Agreement negotiations under new parameters would be a crucial demonstration of the WTO’s capacity to embrace climate action. Crucially, renewed negotiations must expand the scope of the agreement to include environmental services, thereby becoming the Environmental Goods and Services Agreement (EGSA). Expanding this scope would be a major advantage to the UK and other mature, service-oriented economies that have a distinct competitive advantage across the financial, legal, consultancy, and educational markets.

The brave new trade world ushered in by the IRA may provide the critical momentum to achieve results that we could not in 2014-2016. However, as those fundamental disagreements between nations persist, we must be prepared for the possibility of another stalemate. This would provide the credibility and opportunity to convene the touted ‘Climate Club’, as a coalition of nations committed to climate action, as a parallel framework to the WTO in developing trade agreements. The first priority would be development of an enhanced EGSA.

The founding principles must expand the scope of GATT Articles 20(b) and (g) to enable trade exclusionary measures for environmental harms committed both domestically and abroad, whether in the exporting nation itself or elsewhere in their products supply chain.

This agreement should offer clear pathways to the “on-ramps” for aspiring members to access certain benefits (or avoid punitive measures), especially developing countries that are committed to climate action but understandably face a longer runway to achieve emission reductions. Prospective access to the Climate Club would deliver a clear, commercially actionable signal to accelerate decarbonisation in exchange for market access.

Another critical role for the Climate Club would be coordinating the development of carbon leakage measures, namely carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs). As detailed in Policy Exchange’s 2018 report, The Future of Carbon Pricing: Implementing an independent carbon tax with dividends in the UK, the mechanism would help create a level playing field between our domestic industry, which must bear the significant near-term costs incurred for decarbonisation, with foreign competitors from jurisdictions that are not investing in decarbonisation. These foreign industries would incur a carbon tariff when exporting to the UK that would be equivalent to what domestic producers incur under the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Inversely, UK exporters of such goods will be rebated the cost of their carbon compliance at the border when trading with jurisdictions without carbon pricing.

Several jurisdictions are currently considering or adopting CBAMs, most notably the EU, where it comes into effect in October.43Importers will have to account and report embedded emissions, but the tariff itself will only be imposed in 2026 Canada announced its intentions to do so in the fall of 2020 and is consulting with stakeholders.44https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2021/border-carbon-adjustments/exploring-border-carbon-adjustments-canada.html and Even the United States, with Washington’s noted aversion to domestic carbon pricing, is increasingly advancing the idea of border measures, most recently the bi-partisan Prove It Act.45Maxine Joselow, Washington Post. A bipartisan plan to punish global climate laggards: Tax them. 7 June 2023

In the UK, the Environmental Audit Committee of the House of Commons produced a report in March 2022, Greening Imports: a UK carbon border approach, which recommended that “the

Government commence work on this UK carbon border approach immediately, to enable its implementation during the 2020s.” In his Powering Up Britain package in March, Secretary of State Grant Shapps announced a consultation on carbon leakage and vowed to introduce relevant measures before the end of year.46Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, Addressing carbon leakage risk to support decarbonisation. 30 March 2023: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/addressing-carbon-leakage-risk-to-support-decarbonisation

The Climate Club trade framework would deliver an essential convening and coordinating function to achieve alignment on these implementations. Crucially, it would establish common principles to prevent the abuse of carbon leakage and other climate policies for protectionist purposes, and ensure domestic industries remain competitive between openly trading peer economies. As CBAMs expand beyond primary imports like steel and aluminium, the organisation would undertake the difficult work of reaching agreement on calculating carbon intensities on more complicated imports from wind turbine blades to EVs.

Undoubtedly, there will be significant challenges in reconciling the Climate Club’s proposed mandate with prospective members’ existing obligations under the WTO, most notably the MFN clause. But these obstacles are inevitable for any major geopolitical reforms, and overcoming the climate crisis will demand far more demanding compromises from our leadership. The WTO must either enable this evolution from the 20th to the 21st century or witness itself superseded by conflicting plurilateral agreements.

Next chapterSecuring Critical Mineral Resources

China is the world’s pre-eminent source of critical minerals and rare earth metal supplies, including elements like lithium, cobalt, and graphite that are essential for the manufacture of electric batteries, wind turbines and solar panels, few of which can be produced today without passing through a Chinese-owned or operating processing facilities. Left unchecked, this near-monopoly would grant the Chinese Communist Party a geopolitical leverage comparable to that of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in the 1970s.

The UK published its first critical minerals strategy, Resilience for the Future, in July 2022, followed by an update this March, Delivering Resilience in a Changing Global Environment.47HM Government: Resilience for the Future: The United Kingdom’s Critical Minerals Strategy, July 2022. The reports recognise a list of 18 critical minerals48Antimony, Bismuth, Cobalt, Gallium, Graphite, Indium, Lithium, Magnesium, Niobium, Palladium, Platinum, Rare Earth Elements, Silicon, Tantalum, Tellurium, Tin, Tungsten, Vanadium that are of vital importance to our energy security and industrial resilience. While many dozens of elements are required for the climate transition, these 18 are unique because the higher risk factors entailed in using them, including high concentration of reserves within specific geographies/countries, constrained supply chains, presence of monopolistic actors, or non-substitutability across key applications.

Throughout the 20th century, almost all of these elements played a role in various industrial processes, but demand was relatively stable and easily matched by supply. Notably, many of these minor resources were not mined directly, but were extracted as by-products of more mainstream metals, such as cobalt coming from copper mines or indium produced as a result of lead mining. The situation started to evolve in the 1980s with the advent of computers, personal electronic devices, and the batteries that powered them, which required a higher level of technical performance that could only be delivered through the unique chemical properties of these elements.

Beijing realised the growth potential of this sector, and invested tremendous resources and policy direction into supporting the development of domestic minor and rare earth metal mining, processing, and refining. Western companies and their consumers were keen on outsourcing the inherently high environmental impacts, ravenous energy consumption, and difficult labour conditions to distant shores. Reliable access to these commodities was a key feature in attracting further investments up the value-added ladder from primary manufacturing to assemblage. To undercut competition, the Chinese Government provided generous subsidies to their critical mineral sector, allowing them to flood the market with low-cost supply and push the competition out of business. The tens of millions of pounds lost in selling below cost has garnered billions of pounds of foreign investment in advanced manufacturing across China’s industrial clusters.

As domestic reserves began to diminish by soaring consumption, China’s 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-2005) placed a heavy emphasis and financial backing to “Going Global”, encouraging statement owned enterprises (SOE) to scour the world and secure access to the commodities necessary for China’s continued growth.49The Climate & Finance Policy Centre, China’s Mining Industry at Home and Overseas, 2014 For metals, this increasingly meant sourcing from regions scarred by political challenges, including states of the Former Soviet Union, the least developed parts of Southeast Asia, and war-torn Central Africa, most notably the Democratic Republic of Congo. Western companies – averse to the risks of dealing with corruption and human rights violations in those regions – were again complacent and content with Chinese initiative in developing these reserves. Even on minerals over which it has limited domestic reserves, such as cobalt, China has been able to secure global control through a near-monopoly over processing and refining facilities, similarly secured through state subsidies and ruthless cost cutting at the expense of labour and environmental standards. As a result, China dominated critical mineral processing by 2022, leaving little room to its economic rivals:

| Global share of processing; | Europe | US | China |

| Nickel | 10% | 1% | 68% |

| Cobalt | 15% | 0% | 73% |

| Graphite | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Lithium | 0% | 4% | 59% |

| Manganese | 5% | 0% | 93% |

| Rare Earths | 1% | 0% | 87% |

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, 2022