Authors

Content

The ‘Peelian’ Principles of Policing

- To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment.

- To recognise always that the power of the police to fulfil their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour, and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.

- To recognise always that to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also the securing of the willing co-operation of the public in the task of securing observance of laws.

- To recognise always that the extent to which the co-operation of the public can be secured diminishes proportionately the necessity of the use of physical force and compulsion for achieving police objectives.

- To seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion, but by constantly demonstrating absolutely impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy, and without regard to the justice or injustice of the substance of individual laws, by ready offering of individual service and friendship to all members of the public without regard to their wealth or social standing, by ready exercise of courtesy and friendly good humour, and by ready offering of individual sacrifice in protecting and preserving life.

- To use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain public co-operation to an extent necessary to secure observance of law or to restore order, and to use only the minimum degree of physical force which is necessary on any particular occasion for achieving a police objective.

- To maintain at all times a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- To recognise always the need for strict adherence to police-executive functions, and to refrain from even seeming to usurp the powers of the judiciary of avenging individuals or the State, and of authoritatively judging guilt and punishing the guilty.

- To recognise always that the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, and not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with them.

Foreword

Rt Hon Priti Patel MP

former Home Secretary (2019 – 2022)

There are few public services with as vital a mission as policing. The protection of the public and prevention of crime and disorder in our communities is one of the most critical roles of the state.

Time and again as Home Secretary I had the privilege of meeting police officers who had demonstrated the most remarkable courage in protecting the public. I saw complex cases that had only been solved because of the tenacity of committed detectives. I met victims of crimes who were only able to go through the ordeal of giving evidence because of the support of their liaison officer.

However, it is a tragic reality that British policing is in crisis. That one in seven of the 43 police forces of England and Wales are in ‘special measures’ has been a stark wake-up call for Britain’s political and policing leaders. At the core of this crisis is what has become the blurring of the policing mission.

We regularly hear from some Chief Constables and Police and Crime Commissioners that policing resources are strained. Yet, simultaneously there are stories of police forces failing to utilise the resources they do have in the most effective way possible.

This report constitutes the most comprehensive examination of one example of the blurring of that mission. That there are well over 200 Staff Networks operating across the police forces of England and Wales is surprising in itself. That many of these groups are engaging in what has become an unhealthy internal competition for attention and resources rather than pursuing a relentless focus on serving the public is deeply concerning.

To take the name of this report, some of policing’s Staff Networks have blurred the lines between politics and policing. It is critical to our democratic settlement that police officers and staff stick to operational policing while politics is left to democratically elected politicians. This report clearly demonstrates that too often policing’s Staff Networks are crossing that line and failing to maintain the appropriate boundaries of impartiality that are so critically important. This cannot be good for policing, it cannot be good for the public and it cannot be good for our democratic settlement.

If policing is to regain the confidence of the public it must return to a single-minded focus on its crucial mission. Only an urgent and radical agenda for reform will be sufficient.

Policy Exchange has been at the heart of this debate. By following the recommendations outlined in David Spencer’s excellent Policy Exchange report, policing and government can rebalance the role of policing’s Staff Networks. In doing this they will be contributing to enabling everyone in policing to focus on that most vital of missions – keeping the public safe and preventing crime and disorder in our communities.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

The crisis in British policing continues. One of the central critiques of modern policing is that to many people it appears that robbers, drug dealers and fraudsters operate unfettered by the forces of law and order while police officers indulge in activities which too often fail to contribute to effective policing. This paper considers the role of the over 200 ‘Staff Networks’ operating within policing and, while recognising they may have a positive contribution to make, they risk being a significant distraction from policing’s core mission.

Within this report, the term ‘Staff Network’ is used when referring to organisations which focus on the interests of a specific group who self-select by specific characteristics, such as religion, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or disability. They include Networks such as the National Black Police Association (NBPA), the National Association of Muslim Police (NAMP), the Christian Police Association (CPA) and the Disabled Police Association (DPA). Since 2010 the number of national Staff Networks has grown by over 83%.

These Networks are distinct from the formal ‘Staff Associations’ which represent all officers at specific ranks – the Police Federation of England and Wales (PFEW), the Police Superintendents’ Association (PSA) and the Chief Police Officers Staff Association (CPOSA).

This report reveals that Staff Networks operate under a wide range of differing governance mechanisms with varying levels of transparency about their operations. Given Staff Networks operate under the banner of policing with their executives often undertaking activities in police duty time, this paper proposes applying a consistent governance mechanism to all Staff Networks. This report examines as a case study the governance arrangements of one of the best known Staff Networks – the Metropolitan Black Police Association (MetBPA).

The Metropolitan Police states that Staff Networks,

“…provide support; guidance and information to their members and the wider Met to ultimately improve what it’s like to work in the Met for everybody. Our [Staff Networks] are used as a sounding board within the Met, providing their insight to shape how the Met does things, both internally and externally with our communities of London.”1Metropolitan Police Service Website, last accessed 26th January 2023, link

However, the research undertaken as part of this report reveals that Staff Networks within policing are undertaking a far broader range of activities. These activities can be divided into:

- Providing pastoral support to their members, including coaching and mentoring.

- Community engagement and outreach, including supporting forces in making operational policing decisions.

- Supporting police forces to achieve ‘internal’ goals such as achieving recruitment objectives or improved employment conditions for staff through direct activities or by influencing force policies.

- Publicly attempting to influence government or policing policy.

This paper argues that providing pastoral support for colleagues is a legitimate activity and should be supported. Where Staff Networks are undertaking other activities however, far greater care is required.

Where Staff Networks attempt to act as a ‘bridge’ between policing and communities or as an ‘advisor’ in operational policing matters it is essential that the relatively small numbers of individuals involved in running such networks provide advice which is impartial and not affected by the ‘sectarian’ interests of one element of a network over another. In order that operational policing commanders can be assured they are receiving appropriately impartial advice it is essential that information on how each Staff Network operates is available. This would enable policing commanders to assess how much credibility can be ascribed to the information provided, particularly given those involved in Staff Networks are often self-selected from very narrow pools.

Where Staff Networks are influencing internal policies, it is necessary to ensure that they are unable to operate as a ‘pressure group’ which leads policing organisations into pursuing what might be inappropriate policies or activities which are inimical to effective, efficient and impartial operational policing. For example if training on an issue was delivered by an external organisation which publicly holds contested political views, at the request of and with the credibility of a Staff Network, this could have a direct impact on the subsequent ability of police officers to act impartially having received a one-sided perspective on the issue in a training environment.

Where Staff Networks are undertaking the fourth activity, that of publicly attempting to influence policing or government policy, they are straying well beyond the acceptable bounds of political impartiality required of those in policing.

This report examines as case studies the activities of the National Association of Muslim Police (NAMP) and the National LGBT+ Police Network.

‘Policing can win’ over those who would commit crime and disorder in our communities. However, that will only be possible if every person working in policing is focused on that core mission without distraction. The way that several Staff Networks are operating is contrary to enabling forces to achieve their core mission. Given the current crisis in policing, this cannot continue.

Next chapterSummary of Recommendations

- Bring every Staff Network under a consistent internal governance framework. This should include how each Network should be constituted, organised and run at a national and local level. It should be clear that Staff Networks are part of policing and not independent organisations. National Staff Networks should operate under the purview of the National Police Chiefs Council and force-level networks should operate under the purview of the local Chief Constable.

- Where Staff Networks have pre-existing independent arrangements as set out in statute (for example as charities, Community Interest Companies or Charitably Incorporated Organisations) they should be reconstituted to bring them into a consistent internal governance framework as part of policing. If these organisations are unwilling to do so, they should become truly independent with their members and executives no longer permitted to undertake activities in police duty time, they should not be permitted to use publicly funded police resources such as meeting spaces or IT, they should receive no funds from police budgets and the organisations should be treated as external stakeholders. In such circumstances an alternative Staff Network should be created which does operate within the internal governance framework.

- Every Staff Network should have as its primary objective to contribute to improving the effectiveness of policing on behalf of the wider public. It must be explicit that this must over-ride all other considerations.

- There should be full public transparency of how Staff Networks operate. This should include publishing committee memberships, minutes of meetings, workstreams, priorities and budgets.

- The amount of police duty time committed to Staff Network activities should be limited. The balance of every police officer’s and staff member’s work should be overwhelmingly focused on operational duties.

- Staff Networks should be bound by the requirements to remain politically impartial. Police officers and police groups must refrain from publicly lobbying on politically contested issues. This expectation should be made clear as part of the College of Policing’s Code of Ethics. Those who fail to follow these fundamental requirements of policing should be subject to appropriate disciplinary processes.

- Police managers must ensure that, when making policy decisions about both internal and operational matters, they act in the best interest of policing and the wider public. Managers must therefore not give inappropriate undue weight to the views of Staff Networks – an overarching requirement to act in the best interests of the public is paramount. Particular caution should be taken regarding proposals for external, politically active, organisations to deliver training or otherwise influence internal or operational policies.

1. Introduction

A central element of the crisis that has enveloped British policing is the distraction of officers from the core policing mission of keeping the public safe, preventing crime and catching those who would commit crime and disorder in our communities. British policing has a long and successful history, with a model often envied across the globe. One of the features of the last decade in policing has been the significant growth in Staff Networks during that time, with over 200 such networks now operating nationally and within forces across policing. Since 2010 the number of national Staff Networks in England and Wales has grown by over 83%. Although there are no formal figures available it is likely that the total number of Staff Networks, including those based in forces, has grown by at least that proportion.

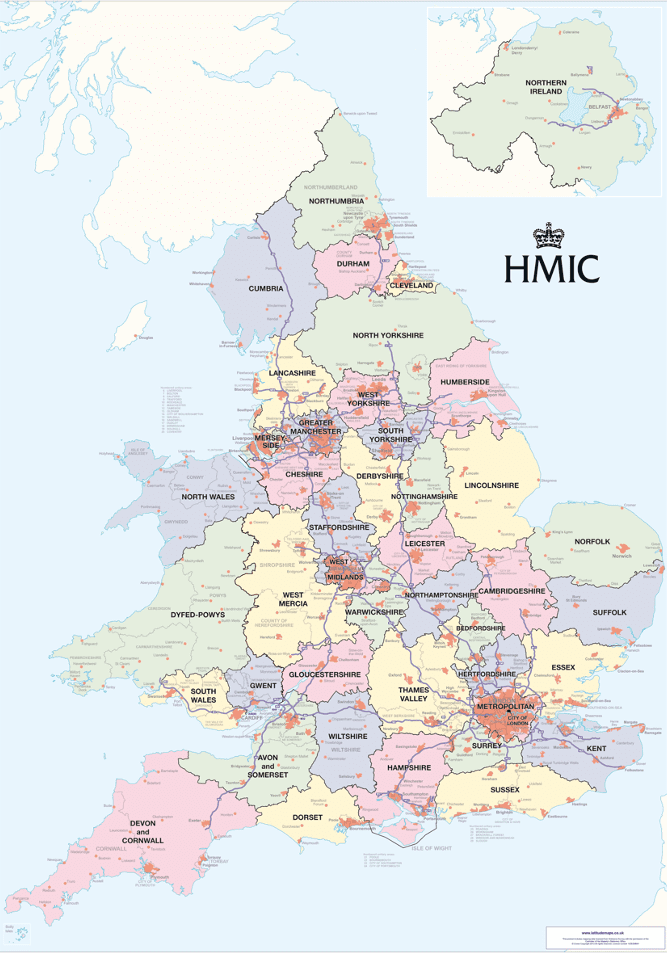

Policing in England and Wales is primarily undertaken by the 43 territorial police forces alongside three additional police forces with more specialist responsibilities (the British Transport Police, the Ministry of Defence Police and the Civil Nuclear Constabulary). Each force is led by a chief constable, or in the case of London’s Metropolitan Police Service and the City of London Police by a police commissioner. Forces range in size from London’s Metropolitan Police Service with 45,145 officers and staff to the City of London Police with 1,361 officers and staff.

Police forces of England, Wales and Northern Ireland2His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services, link

In addition to operational police forces a series of national policing bodies exist to set standards of recruitment, training and operational police practice as well as to co-ordinate policing across force boundaries. The College of Policing is policing’s ‘professional body’ and is an “operationally independent arms-length body of the Home Office”.3College of Policing Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link The National Police Chiefs’ Council performs a co-ordinating function nationally and is chaired by a chief constable elected by chief police officers from within their number.

Police officers are not permitted, by law, to join a trade union and as such they are formally represented, dependent on their rank, by one of a number of ‘Staff Associations’ – the Police Federation of England and Wales (PFEW), the Police Superintendents’ Association (PSA) and the Chief Police Officers Staff Association (CPOSA). There are similar organisations to the PFEW and PSA representing officers in Scotland and Northern Ireland, whilst CPOSA represents chief officers across all four UK nations.

Section 2 of this report provides a short summary of the formal arrangements surrounding the Staff Associations in policing.

In addition to the formal Staff Associations police officers and staff are also able to join Staff Networks. These Networks focus on the interests of specific groups who self-identify by specific characteristics, such as religion, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or disability. Nationally, they include groups such as the National Black Police Association (NBPA), the National Association of Muslim Police (NAMP), the National LGBT+ Police Network, the Christian Police Association (CPA) and the Disabled Police Association (DPA). In addition to organising on a national level there are also separate, but sometimes affiliated, Staff Networks which operate at a force level.

Section 3 of this report provides a detailed examination of the governance and activities of policing’s Staff Networks.

Next chapter2. The Staff Associations

The Police Federation of England and Wales: The Police Federation of England and Wales is the Staff Association representing all police constables, sergeants, inspectors and chief inspectors working within the police forces of England and Wales. They are one of the largest staff associations in the UK, representing more than 130,000 rank and file officers.4Police Federation of England and Wales Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link Although membership of the Police Federation is voluntary, the vast majority of officers at the relevant ranks are members.

Originally established in 1919 the Police Federation has a statutory responsibility for the welfare and efficiency of their membership alongside an obligation to act in the public interest.5Ibid The detailed governance and working arrangements of the Police Federation are set out in statute via The Police Federation (England and Wales) Regulations 2017.6The Police Federation (England and Wales) Regulations 2017, link

The Federation has a statutory role to represent its membership in relation to individual allegations of misconduct and other complaints, as well as the collective representation of its membership relating to their terms and conditions of appointment. The Federation is represented across a range of formal policing boards and governance forums, for example holding seats on the board of directors of the College of Policing7College of Policing Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link and the Police Advisory Board8Police Advisory Board Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link for police pensions, as well as attending the National Policing Board9National Policing Board Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link to contribute on matters relating to frontline policing.

Similar organisations to the Police Federation of England and Wales exist in Scotland and Northern Ireland to represent officers in those nations.

The Police Superintendents Association: The Police Superintendents Association represents police superintendents and chief superintendents in the 43 police forces in England and Wales, the British Transport Police, the Civil Nuclear Constabulary and a number of the forces covering overseas territories. They represent approximately 1,500 officers across those forces.

A series of conferences and meetings between 1920 and the early 1950s led to an early form of representation for superintendents before the formal creation of the Police Superintendents Association of England and Wales in 1952.10Police Superintendents Association Website, last accessed 26th November 2022, link In 2018 the Police Superintendents Association became a private limited company11Ibid but it is not governed by a statutory regime of the nature which governs the Police Federation of England and Wales.

The Articles of Association for the PSA states that they seek, “to negotiate the best possible conditions of service for members, and to provide support and advice to members regarding health and welfare or those ‘at risk’ in relation to conduct issues.”12Police Superintendents Association, Articles of Association, 18th October 2018, link Additionally, the Superintendents’ Association seeks, “to help lead and develop the police service to improve standards of policing” and “to actively contribute to helping to shape future policing policy and practice at the national and strategic levels.”13Ibid The Association is represented on a range of policing boards and governance forums, including the board of directors of the College of Policing14College of Policing Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link, as well as attending the National Policing Board15National Policing Board Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link on matters relating to frontline policing.

Similar organisations to the Police Superintendents Association exist in Scotland and Northern Ireland to represent officers in those nations.

The Chief Police Officers Staff Association: The Chief Police Officers Staff Association (CPOSA) represents chief police officers and senior police staff across the UK’s police forces. Its stated aims are to “ensure that terms and conditions of service are considered and [to offer] advice, guidance and support in relation to welfare” to its membership of around 400 officers and staff.16Chief Police Officers’ Staff Association Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link

Following the 2013 Parker Review of the Association of Chief Police Officers17General Sir Nick Parker KCB CBE, Independent review of ACPO 2013, link, CPOSA became an independent and private company limited by guarantee in 2015.18Chief Police Officers’ Staff Association, Certificate of Incorporation, 16th January 2016, link CPOSA is represented across a series of policing governance committees including the Police Advisory Board19Police Advisory Board Website, last accessed 23rd December 2022, link relating to police pensions and the staff side of the Police Negotiating Board.20Police Negotiating Board, Constitution of the Police Negotiating Board, link

Next chapter3. The Staff Networks

The origins of policing’s Staff Networks stretch back to the formation of the Christian Police Association, established in 1883 by Catherine Gurney OBE.21Christian Police Association (2016), A short history of the Christian Police Association, link Although Gurney was not a police officer nor member of police staff herself, she had become concerned for the ‘spiritual welfare’ of the police. In addition to playing a central role in founding the Christian Police Association she also went on to establish the first convalescent home exclusively for police officers.22Ibid

Recent years have seen a substantial increase in the number of Staff Networks established both nationally and within forces. While this growth may be reflective of a similar pattern in other workplaces it is a trend particularly worthy of examination given policing’s unique position within our society. It is inescapable that whilst policing has many individuals who serve the public honourably with unstinting courage and commitment, there are elements of the policing culture which have demonstrated itself to be a more challenging environment for those who are ‘different’. Given this environment it is perhaps unsurprising that Staff Networks have become so prolific across the police service; whether they are leading to more effective policing on behalf of the public is however a crucial question.

The Governance of Police Staff Networks

There are at least eleven Staff Networks operating nationally within policing, covering a range of characteristics.23Joining the Police Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link There are currently no consistent governance arrangements for how these Networks operate. Two of the eleven Staff Networks are registered as charities – the Christian Police Association24Christian Police Association, Charity Commission Record, link (CPA) and the National Black Police Association25National Black Police Association, Charity Commission Record, link (NBPA). The National Sikh Police Association26National Sikh Police Association UK, Charity Commission Record, link (NSPA) is registered as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO). The National Association of Muslim Police27NAMP CIC, Companies House Record, link (NAMP) is registered as a Community Interest Company (CIC). Where Networks are registered as a charity, a CIC or CIO they are legally required to publish how they will operate, usually through their Articles of Association. Although not formally required, some Staff Networks which are not formally registered have nonetheless published constitutions or similar documents which outline in detail how they operate (such as the Jewish Police Association28Jewish Police Association (2009), Constitution of the Jewish Police Association, link). While most Networks do publish their broad aims and objectives on their websites, many Staff Networks have not published a formal constitution or similar document which outlines how they make decisions, how their executive committees are chosen or how they organise their activities.

It is possible for individual police officers and staff to join some of the national Networks directly, although this is not universally the case. Generally, the larger Networks (including the National Black Police Association, the National Association of Muslim Police and the LGBT+ Police Network) operate purely as national ‘umbrella’ organisations which the force-level affiliate Networks then join. In these cases it is not possible for individuals to directly join the national grouping directly and members must join their local force Network.

Table 1: National Police ‘Staff Networks’29A Chief Constables’ Council paper titled “Proposal to establish a national Internal Stakeholder Engagement Group” dated the 11th August 2022 does refer in Appendix B to a ‘Hindu Police Association’, however given this association is not listed on the Home Office run ‘Joining the Police’ website and the association appears to have no formal website presence they have not been included in this list.

| National Staff Network | Year Established | Formal registration | Published Constitution | Direct Membership/ Network |

| Christian Police Association | 1883 | Charity30Registered in 1964, link |

Yes | Both |

| British Association for Women in Policing | 1987 | None | No | Unclear |

| National Black Police Association | 1998 | Charity31Registered in 2002, link |

Yes | Network |

| Jewish Police Association | 2001 | None | Yes | Direct |

| National Association of Muslim Police | 2007 | CIC32Registered in 2021 as a Community Interest Company, link |

Yes | Network |

| National Police Pagan Association | 2009 | None | No | Direct |

| Disabled Police Association | 2012 | None | No | Direct |

| Gypsy Roma Traveller Police Association | 2014 | None | No | Direct |

| National Police Autism Association | 2015 | None33The National Police Autism Association website states it is “Owned, funded and run by a police officer”, link |

No | Direct |

| National LGBT+ Police Network | 201534Although the National LGBT+ Police Network was founded in August 2015, a predecessor organisation, the Gay Police Association, existed from 1990 to 2014. |

None | No | Network |

| National Sikh Police Association | 2019 | CIO35Registered as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation in 2020, link |

Yes | Direct |

In addition to the national groups there are also Staff Networks which operate at a force level, often affiliated or linked with the relevant national Network. The number of Staff Networks within each force varies considerably. Most forces have between five and eight groups although the Metropolitan Police Service has at least twenty operating. Almost every force has a different Staff Network dedicated to each of: ethnic minority staff, women or gender equality, staff with a disability and LGBT+ staff. In total there are over 200 individual Networks operating across the forces of England and Wales.36See the Appendix of this report for a list of all of the identified Staff Networks nationally and across the 43 territorial forces of England and Wales

| The Metropolitan Police Service’s Staff Networks37Metropolitan Police Service Website, last accessed 24th November 2022, link – the Metropolitan Police Service refers to their Staff Networks as ‘Staff Support Associations’ |

| The Association of Muslim Police

Association of Senior Women Officers British Association for Women in Policing London Christian Police Family Metropolitan Police LGBT Network Jewish Police Association Metropolitan Black Police Association Metropolitan Police Service Chinese and South East Asian Staff Association Metropolitan Police Humanists Metropolitan Police Service Emerald Society Metropolitan Police Service Greek & Cypriot Association Metropolitan Police Hindu Association Metropolitan Police Ibero-American Association Metropolitan Police Italian Association Metropolitan Police Polish Association Metropolitan Police Sikh Association Metropolitan Police Disability Staff Association Metropolitan Police Service Turkish Police Association Metropolitan Police Romanian Association Network of Women |

While most of the Staff Networks are based on self-selected specific characteristics, such as religion, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or disability there are a number which stray beyond these boundaries. Two examples are the Cleveland Police Vegan Network and the West Yorkshire Green Police Network.

Cleveland Police, which the former Chief Inspector of Constabulary Sir Tom Winsor described in April 2022 as the ‘worst performing force in the country’38‘Police Watchdog Tom Winsor’, Financial Times, 8th April 2022, link, nonetheless has a Vegan Network listed as one of Cleveland Police’s ‘Staff Networks’ contributing to “foster[ing] an inclusive working environment in which every employee feels valued and supported”.39Cleveland Police Website, last accessed 24th November 2022, link Although the Vegan Network does not appear to have its own website it is also listed as part of the force’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2020-2025. The strategy states that “Cleveland Police Vegan Network supports the Everyone Matters programme and fully believe in being: Compassionate, Respectful and Considerate”. In 2018 there were reportedly “close to 20 members” of the Vegan Network, although not all twenty were apparently vegans.40Cleveland Police Facebook (9th August 2018), last accessed 23rd November 2022, link

According to the West Yorkshire Police website, the West Yorkshire Green Police Network exists to provide support, advice and guidance to its membership and other colleagues in relation to “green/ethical and dietary matters”.41West Yorkshire Police Website, last accessed 24th November 2022, link The West Yorkshire Police website states that its Green Police Network exists to “influence West Yorkshire Police policy development in making positive changes in relation to these matters, whilst building an effective network which benefits its members and wider Officers and staff”.42West Yorkshire Police Website, last accessed 24th November 2022, link Given the primary role of Staff Networks has traditionally been focused on providing support to those groups who are under-represented in policing, this Staff Network appears to be exceptional by being primarily focused on influencing policy. It is worth posing the question whether it would be considered permissible for other Networks to be established which exist primarily to lobby in relation to other policy issues which staff members might consider to be important.

Staff Networks are frequently engaged by forces to be closely involved in the development of policies across a broad range of activities. Given this it is reasonable to ask who the individuals are who have been selected to undertake decision-making roles within Staff Networks and how they have been selected. Different Networks take differing approaches in relation to making this information publicly available. While the Metropolitan Black Police Association for example publishes the names and photographs of its entire Executive Committee43Met Black Police Association Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link, others such as the Police Emerald Society GB and MPS Greek & Cypriot Association list only a series of obscure acronyms such as “Mr P.O’D”, “Mr J.M”, “Tom H-S”.44Police Emerald Society GB Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link and Metropolitan Police Service Greek and Cypriot Association, last accessed 25th November 2022, link

Dependent on their structure, organisations which are registered as charities, Community Interest Organisations (CIO) or Charitable Interest Companies (CIC) are required to provide information regarding their trustees or directors with Companies House or the Charity Commission. An examination of the relevant registers for the four national Staff Networks which are registered as charities, CICs or CIOs suggests an inconsistent approach to how trustees or directors are selected and registered.

The National Black Police Association (NBPA) lists two trustees on the Register of Charities45National Black Police Association, Charity Commission Record, last accessed 28th November 2022, link, only one of whom is also listed on the NBPA’s website.46National Black Police Association Website, last accessed 28th November 2022, link Meanwhile, four of the NBPA Cabinet are not listed as trustees including the Chair.47Ibid

The National Association of Muslim Police lists two directors with Companies House48Companies House Register for NAMP CIC, last accessed 28th November 2022, link while the remaining seven members of the NAMP Executive Board are not listed.49National Association of Muslim Police Website, last accessed 28th November 2022, link Notably one of NAMP’s two directors registered with Companies House is currently listed on NAMP’s website as ‘taking a break from her duties’.50National Association of Muslim Police Website, last accessed 28th November 2022, link It is perhaps not unreasonable to ask whether the sole remaining trustee is therefore acting alone in fulfilling their legally mandated duties.

The National Sikh Police Association lists eleven members of their Executive Team on their website, while only four of the eleven are listed as trustees on the Register of Charities.51Charity Commission Register for National Sikh Police Association, last accessed 28th November 2022, link

The Christian Police Association lists sixteen trustees on the Register of Charities52Charity Commission Register for Christian Police Association, last accessed 28th November 2022, link, although only eleven individuals are listed on the CPA’s ‘Our Team’ section of their website.53Christian Police Association Website, last accessed 28th November 2022, link

There is certainly no legal requirement for every member of a Network’s executive body to be, or to be listed as a trustee or director, nor for every trustee or director to be a member of the executive body listed on a Network’s website. However, this lack of consistency across the four Networks suggests a lack of clarity or consensus as to which individuals are the most appropriate to be formally and legally responsible for the activities of Staff Networks. This cannot be a situation that is in the best interests of either policing or the public.

Case Study: The Met Black Police Association (MetBPA)

Although not the first Staff Network established within policing, the Black Police Association is perhaps the best known. During the late 1980s and early 1990s a series of initiatives by officers and staff within the Metropolitan Police raised concerns over the high numbers of black officers who were leaving policing. These meetings, known as the ‘Bristol Seminars’, led to the formation of a support network for black officers, eventually culminating in the creation of the Metropolitan Black Police Association in 1994 and the National Black Police Association in 1998.54National Black Police Association Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link The creation of the Black Police Associations received the support of the then Metropolitan Police Commissioners and subsequent Home Secretaries.55ibid

The MetBPA has its own constitution with full voting-rights membership open to, “serving police officers, special constables and police staff directly employed by the MPS [Metropolitan Police Service], MOPAC [Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime] or retired or former members who are of African, African-Caribbean, or Asian origin.”56Met Black Police Association, Membership Constitution, last accessed 24th November 2022, link While applicants to the Association self-declare their origin as part of their application57Met Black Police Association, Membership Application, last accessed 24th November 2022, link, according to the MetBPA’s constitution the Executive Committee reserves the right to refuse membership, apparently without explanation.58Met Black Police Association, Membership Constitution, last accessed 24th November 2022, link It is unclear what would constitute a reason for refusal. Non-voting associate membership is available to those officers and staff who do not meet the full criteria either by not working for the Met or MOPAC or not being of African, African-Caribbean, or Asian origin. The cost of full membership is an annual payment of £20.59Met Black Police Association, Membership Application, last accessed 24th November 2022, link

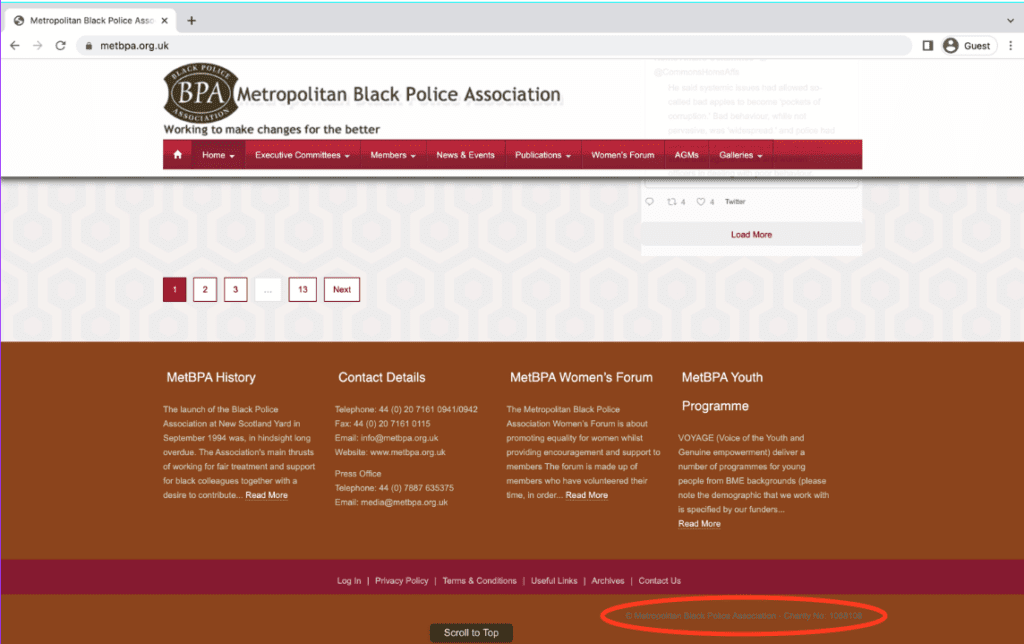

The Met Black Police Association has a note on its website which states, “© Metropolitan Black Police Association – Charity No: 1068108”60Met Black Police Association Website, last accessed 22nd November 2022, link. However, according to the Charity Commission’s register of charities, the MetBPA does not actually appear to be charitably registered.61There is no apparent entry for the MetBPA on the Charity Commission Website (last accessed 25th November 2022) although the National BPA is registered (Charity number: 1093518), link The charity number quoted on the MetBPA website actually relates to a separate and independent charity called Voice of Youth and Genuine Empowerment (VOYAGE). While VOYAGE was founded in 1998 by members of the MetBPA (and was originally known as the Black Police Association Charitable Trust), it now appears to be a separate and independent organisation.62VOYAGE Website, last accessed 26th November 2022, link Charitable registration is a detailed and laborious process, governed by statue, which provides organisations with certain advantages and obligations.63Primarily through the Charities Act 2011, link Given the MetBPA is not charitably registered, despite the entry on their website, they are therefore not entitled to the advantages conferred upon charities nor required to comply with the governance obligations required of charities. There is certainly nothing to suggest that the website entry is anything other than an innocent error (rather than for example an active effort to deceive), it does raise questions as to whether the MetBPA’s existing governance arrangements are sufficiently robust given they seem unable to prevent such basic mistakes from occurring.

MetBPA Website indicating Charity Number 1068108, which is the charity number for the organisation ‘VOYAGE’64Met Black Police Association Website, last accessed 15th December 2022, link

The MetBPA is one of a small number of Staff Networks within the Metropolitan Police which are permitted to have a police officer post committed to its work full-time. It is unclear how the small number of Staff Networks which are permitted to have a funded full-time post dedicated to its work have been selected but it is difficult to avoid the perception that the Met has created an unofficial ‘hierarchy’ of the differing Staff Networks.

As part of the MetBPA’s arrangements the Network has a Code of Ethics within its Constitution65Met Black Police Association Constitution, Article 10, link and a separate Code of Conduct.66Met Black Police Association Code of Conduct, link Much of the contents of the MetBPA Code of Ethics is laudable, with strong similarities to the College of Policing’s Code of Ethics that all police officers and staff are required to abide by.67College of Policing, Code of Ethics, link However, the MetBPA Code of Ethics states that executive members should, “take decisions solely in terms of the MetBPA interest. They should not do so in order to gain financial or other material benefits for themselves, their families or their friends.”68Met Black Police Association Constitution, Article 10, link In the event that an executive member of the MetBPA might be required to make a decision which would require ‘trade-offs’ between the best interests of the public, the wider police service or the MetBPA it appears that the MetBPA Constitution suggests that the MetBPA’s interests should take primacy. This cannot be right for a group which exists as part, or at the very least is perceived as being part, of policing.

In addition to the long-established Met Black Police Association another grouping for black officers within the Met, the Black Police Networking Strand (BPNS), was established in 2021.69Metropolitan Police Service Quarter 3 2020-21: Business Plan progress report, p. 27, link The BPNS was apparently modelled on a similar initiative previously trialled by the Met’s most senior female black officer, in another force.70MyLondon News, 27th April 2022, link The BPNS aims to introduce the public to black police officers via outlets such as podcasts and social media channels an effort to improve the Met’s recruitment objectives.71Ibid

It is intriguing that the BPNS was created despite the long-established MetBPA already existing. Based on publicly available information, it would certainly appear that there was concern within the National Black Police Association at the creation of the BPNS. In March 2022 the Chair of the National Black Police Association commented critically on the BPNS and the female black police constable who created it.72Twitter, @andygeorgeni, 27th March 2022, link – although the news article which this tweet links to has since been removed from the Met’s website it remains available via the webarchive, link

The MetBPA is a long-established Staff Network which has been distinguished by having many outstanding police officers and staff as members. Many members have made significant contributions to policing and serving the public. However, the existing governance arrangements suggest that neither the public nor everyone working in policing can be entirely confident that the MetBPA is operating in a way which is demonstrably leading to better outcomes for the wider public and the police service as well as their own members. A new governance framework, consistent for all Staff Networks, could provide that confidence to the public and to the entire policing workforce.

It is apparent that there is no consistency of governance and oversight for differing Staff Networks at a national or force level. In particular, it is unclear whether Staff Networks are in effect operating as part of the formal policing infrastructure provided by forces and national policing bodies, or are independent organisations, or are organisations which are attempting to operate as some kind of hybrid body.

It is particularly the case that if Networks are charitably registered (or registered as Community Interest Companies or Charitable Incorporated Organisation) they are, in reality, already independent organisations which cannot therefore operate under the purview and governance of the formal policing infrastructure. It is highly questionable whether this is an appropriate framework for a Staff Network in policing, particularly given the sensitivity of policing’s role in society and the broad range of activities within policing that Staff Networks are involved in.

Given there are hundreds of Networks operating nationally within and across forces the lack of consistent governance arrangements is likely, at the very least, to be leading to significant inefficiencies across policing. This cannot be in the best interests of the public. It is therefore necessary that a consistent governance and oversight regime is applied to these organisations at both a national and force level. Ensuring that they are operating in the best interest of the wider public is essential – there can be no more important role for any Network that is part of policing.

Were the opacity of the governance arrangements the only issue this would be concerning. However, when the actual activities of some Staff Networks are examined, it is clear the issues run much deeper. They are considered in the next section.

The Activities of Police Staff Networks

The Metropolitan Police states that,

“The [Staff Networks] provide support; guidance and information to their members and the wider Met to ultimately improve what it’s like to work in the Met for everybody. Our [Staff Networks] are used as a sounding board within the Met, providing their insight to shape how the Met does things, both internally and externally with our communities of London.”73Metropolitan Police Service Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link

However, it is clear that the activities of Staff Networks in policing often go far further than might be imagined given this limited description. The activities of Staff Networks can broadly be divided into four categories:

- Providing pastoral support to their members, including coaching and mentoring.

- Community engagement and outreach, including supporting forces in making operational policing decisions.

- Supporting police forces to achieve ‘internal’ goals such as achieving recruitment objectives or improved employment conditions for staff through direct activities or influencing police policy design.

- Publicly attempting to influence government or policing policy.

Where Staff Networks are providing pastoral support for colleagues these activities are likely to be legitimate and should be supported by policing and government.

Where Staff Networks attempt to act as a ‘bridge’ between policing and communities it is essential that the relatively small numbers of individuals involved in running such Networks provide advice which is impartial and not affected by the ‘sectarian’ interests of one element of a network over another. A safeguard to ensure that operational policing commanders can be assured they are receiving appropriate and impartial advice is essential. To enable this, information must be available on how each Staff Network operates in order that commanders can assess how much credibility can be ascribed to the information and advice they receiv. This is particularly necessary given those involved in Staff Networks are often self-selected from a very narrow pool of officers and staff.

Where Staff Networks are undertaking the third activity, that of influencing internal policies, far greater care is required to ensure that they are not operating as an internal ‘pressure group’ which leads policing organisations into pursuing what might be inappropriate policies or activities. It is incumbent on leaders across policing and government to be alive to this potential risk and, if necessary, intervene to prevent the introduction of policies which may be advocated by Staff Networks but may be inimical to effective and efficient policing. For example, if a Staff Network requested that training be delivered by an organisation with known, and contested, political views on a matter, this could have a direct impact on the ability of police officers to act with impartiality, as they may receive a one-sided perspective on the issue in a training environment.

Where Staff Networks are undertaking the fourth activity, that of publicly attempting to influence policing or government policy, they are straying well beyond the acceptable bounds of political impartiality required of those in policing.

The fundamental ‘Peelian’ principles of British policing74The ‘Peelian’ Principles of Policing are often considered the fundamentals on which British policing is based. They first appeared as an appendix to A New Study of Police History by Charles Reith (1956). For more on their creation see S. Lentz & R. Chaires (2007), The invention of Peel’s principles: A study of policing ‘textbook’ history, Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 35 (1), pp. 69-79, link remain one of the bedrocks of British policing. Police officers are instructed, “to seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion, but by constantly demonstrating absolutely impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy…” Policing’s contemporary Code of Ethics is similarly clear in relation to the expectations of police officers in relation to membership of other groups and not permitting officers to be involved in political activity.

| Police Code of Ethics75College of Policing, Code of Ethics, July 2014, link |

| “Associations

6.3 Membership of groups or societies, or associations with groups or individuals, must not create an actual or apparent conflict of interest with police work and responsibilities. 6.4 The test is whether a reasonably informed member of the public might reasonably believe that your membership or association could adversely affect your ability to discharge your policing duties effectively and impartially. Political activity – police officers only 6.5 Police officers must not take any active part in politics. This is intended to prevent you from placing yourself in a position where your impartiality may be questioned.” |

Despite these requirements it has become increasingly common for police officers, and Staff Networks in particular, to publicly wade into political debates. The track record of police officers intervening on contested policy issues is neither new, nor has it only been limited to relatively junior officers from Staff Networks. In the run up to the 2005 general election, when most public servants were constrained by purdah from even the most mundane of tasks or statements, the then Commissioner of the Met announced his support for the Labour Party’s proposal to introduce identity cards. For a senior police officer to make such an overtly partisan intervention during an election campaign was rightly condemned by many commentators at the time, but the die was cast for all and sundry in policing to feel they could publicly share their views on whatever issue came along.

Case Study: National Association of Muslim Police (NAMP)

The National Association of Muslim Police (NAMP) was established in 2007, at an event at the British Transport Police headquarters, with Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) Secretary General Dr Abdul Bari speaking.76‘Launch of National Association of Muslim Police at the British Transport Police’, International Quran News Agency, 21st July 2007, link By 2021 NAMP claimed to have 1000 members in police forces, with 13 local associations.77National Association of Muslim Police, Membership and Community Survey Report, 2021, link p. 3 NAMP gives little further detail in terms of breaking down its membership by age, gender, ethnic background or sectarian affiliation. It is unclear for example, to what extent Muslim minorities such as Shia or Ahmadis are present. On its website, the organisation lists four workstreams78National Association of Muslim Police Website, last accessed 24th November 2022, link:

- Inclusivity in the workplace

- Anti-Muslim Hatred

- Counter-Terrorism

- Muslim Representation.

However, within these workstreams, NAMP has regularly moved into overtly political commentary and public lobbying, a troubling practice given the expectations for policing to remain politically impartial.

On the 14th November 2022, NAMP issued a statement calling on the Home Office and police forces to change the terminology used when discussing terrorism.79Twitter, @Official_NAMP, 14th November 2022, link NAMP specifically objected to the terms “Islamist”, “Islamism” and “Jihadist”. NAMP argued the use of these words raises three specific areas of concern: “increased levels of Islamophobia, greater risks of radicalisation, lower levels of trust and confidence.”80National Association of Muslim Police, National Association of Muslim Police calls for updating Counter Terrorism terminology, 14th November 2022, link In its place, NAMP proposes changes in terminology to “Daesh Inspired Terrorism”, “Irhabism”, or “Anti-Western Extremism”. NAMP made these proposals previously, in a paper published in March 2022, additionally stating:

“Those with right wing views may feel that the new terms are not accurate descriptions due to the lack of a direct connection to Islam. This may result in conspiracy theories, negative publicity of the police service and rise in Islamophobia in the short term.”81National Association of Muslim Police, Proposal for Changes to Counter-Terrorism Terminology, 17th March 2022, link, p. 5

It is difficult to conceive of a more political approach for a police Staff Network to take than to wade into the traditional left-right divide of British politics and to then, without simultaneously providing any evidence to support the claim, assign a particular position to those on one side of the political divide.

NAMP’s March 2022 statement concludes that “NAMP would like to see this inform and influence change within the CONTEST Strategy 2022.”82National Association of Muslim Police, Proposal for Changes to Counter-Terrorism Terminology, 17th March 2022, link, p. 5 Given CONTEST is the government’s overarching counter-terrorism strategy, it is clear that NAMP is seeking to influence government policy through a process of public lobbying. The statement by NAMP in November 2022 is particularly notable as it closely follows a government announcement on the 30th October 2022 of a ‘refresh’ of the CONTEST counter-terrorism strategy.83Home Office: Review of government counter-terror strategy to tackle threats, 30th October 2022, link

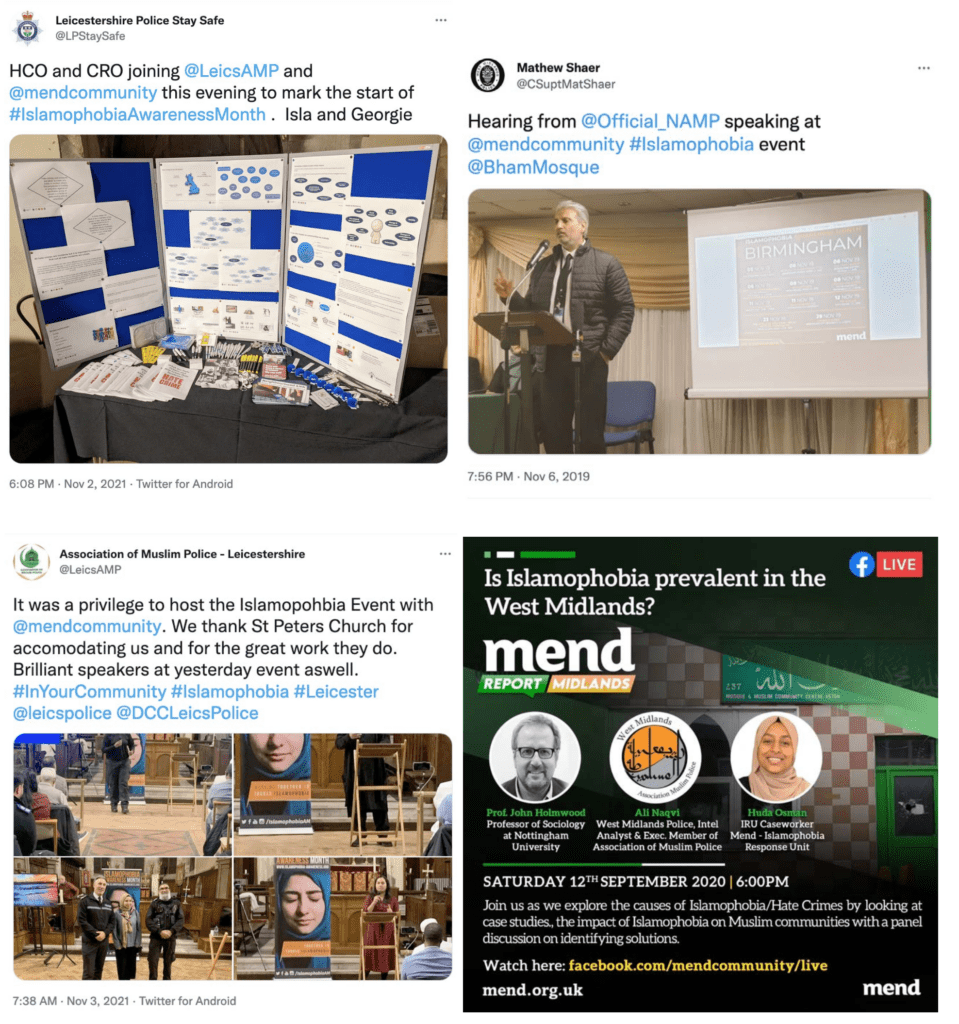

Straying into political debates is consistent with NAMP’s history, indeed it has campaigned as part of the annual Islamophobia Awareness Month, appearing on the campaign’s website as a supporter of the 2022 campaign.84Islamophobia Awareness Website, last accessed 9th January 2023, link Central to Islamophobia Awareness Month is the campaign for the recognition of the definition of ‘Islamophobia’85See for example the Islamophobia Awareness Month website ‘Community Pack’, link, p. 6 ‘ proposed within the 2018 report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims which takes a wide-ranging approach to defining ‘Islamophobia’.86All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims (2018), Islamophobia Defined, link The proposed concept of ‘Islamophobia’ and the examples provided within the report are so broad ranging as to potentially risk equating criticism of a faith – Islam – with prejudice against Muslims themselves. In a liberal democracy where ‘free speech’ is a core value, whilst individuals should be (and in the UK are) protected by the law from violence or discrimination on the grounds of their faith, people should surely remain free to criticise a religion more broadly. For this and other reasons, including incompatibility with the Equality Act 2010, the government rejected the definition of Islamophobia as proposed by the All-Party Parliamentary Group of British Muslims.87Hansard, House of Commons, 16th May 2019, link For NAMP to be involved in a campaign whose central feature is contrary to existing government policy strays beyond the bounds of what is acceptable for an organisation operating within policing and which therefore should be making every effort to remain politically impartial.

It is also worth noting the campaigning nature of one of the organisations which NAMP and other local force Muslim associations have chosen to work with, Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND). Over recent years Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND) has devoted considerable energy to campaigning against a key aspect of Britain’s counter-terrorism strategy, the Prevent policy, which aims to stop people from committing or being involved in acts of terrorism. A 2021 article on MEND’s website, for example, called for Prevent to be abolished and claimed, “Muslims are being specifically singled out for referrals.”88MEND, ‘Time for Prevent to be scrapped’, 13th July 2021, link It is notable that official data indicates that only 22% of referrals to Prevent are of individuals suspected of Islamist extremism, a proportion which has declined by 79% since 201689Home Office, Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, England and Wales, April 2020 to March 2021, 18th November 2021, link with referrals concerning far-right extremism now outnumbering those for Islamist extremism. This is despite the fact that Islamist terrorism remains the most substantial terrorist threat faced by the United Kingdom, equalling some three-quarters of the Security Service’s counter-terrorism workload.90Director General Ken McCallum gives annual threat update, Security Service, 16th November 2022, link

It is clear that there have been concerns at the most senior levels of policing regarding MEND. In 2018 the current Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, who was then the national policing lead for Counter Terrorism, Sir Mark Rowley QPM, criticised MEND for making inaccurate claims stating,

“Leaders of MEND have claimed the UK is approaching the conditions that preceded the Holocaust, seeking to undermine the State’s considerable efforts to tackle all hate crime and making an absurd comparison with state-sponsored genocide. One of MEND’s former leading figures lost a libel case labelling him as “a hard-line Islamic extremist” in the context of comments he made supporting the killing of British soldiers in Iraq.”91Mark Rowley, ‘Extremism and terrorism, the need for a whole society response: The Colin Cramphorn Memorial Lecture’, Policy Exchange, 26th February 2018, link

Despite the campaigning nature of MEND and criticism from the highest levels of the police service there are examples of local force Muslim associations and NAMP representatives working with MEND and speaking at MEND events. Recent examples of this can be seen with officers working with MEND in Birmingham in 201992Twitter, @CSuptmatShaer, 6th November 2019, link, West Midlands (an online event) in 202093MEND Website, last accessed 9th January 2023, link and Leicestershire in 202194Twitter, @LPStaySafe, 2nd November 2021, link & Twitter, @LeicsAMP, 3rd November 2021, link.

These partnerships are surely, at best, a deeply unwise approach for an organisation from policing to be undertaking.

While many police officers and staff who are members of the National Association for Muslim Police and similar local staff networks are no doubt undertaking important work in their operational posts, the actions by NAMP in publicly lobbying for changes to government policy are politically partisan in nature and are inappropriate for a Staff Network in policing to be undertaking. They should not continue.

Case Study: The National LGBT+ Police Network

The National LGBT+ Police Network was established in 2015 following the closure of a predecessor organization, the Gay Police Association during the previous year. The National LGBT+ Police Network does not give individuals the opportunity to join the Network, with only individual force-level groups permitted to join the national Staff Network. The Network’s national co-ordination group members are listed on its website. They are apparently elected to the national co-ordination group, although it is unclear how these elections operate.

The National LGBT+ Police Network website states its priorities are to95National LGBT+ Police Network Website, last accessed 12th December 2022, link:

- Provide a reference to stakeholders in the Police Service, the wider criminal justice sector and LGBT+ organisations on LGBT+ issues in policing

- Support the development of local and regional LGBT+ staff networks

- Represent local and regional LGBT+ staff networks on issues collectively faced

- Support police forces and national police establishments in the development of operational policing knowledge and services that will enhance services to the LGBT+ community

- Support police forces and national police establishments in being representative and inclusive of the LGBT+ community

However, beyond these workstreams the National LGBT+ Police Network does stray into more overtly political territory. This is a practice which is beyond both its own stated priorities and is concerning given the expectations for those in policing to remain politically impartial.

On the 31st August 2020, in response to campaigners seeking to exclude police officers from marching as part of the annual Pride in London event, a serving Metropolitan Police Chief Inspector who was also the Chair of the Met’s LGBT+ Network, wrote a blog published on the National LGBT+ Police Network’s website making the case that officers should be permitted to attend and march in uniform.96‘Get the Police Out Of Pride’, National LGBT+ Police Network Website, last accessed 12th December 2022, link Although not specifically articulated, given the need for police officers to remain politically impartial, part of the case for police officers to attend is presumably based either on a claim that the event is not political or that this case should be an exemption.

While the Pride in London event may well be intended partly as a show of solidarity against discrimination, it is also very clearly a political event. This was recently most clearly demonstrated as part of the 2022 Pride in London event, where organisers made a series of policy demands from government97Pride in London Website, last accessed 12th December 2022, link:

- A ban on conversion therapy for all LGBT+ people;

- Reform of the Gender Recognition Act;

- The provision of equal protection for LGBT+ communities against hate crime;

- An end to its hostile environment toward migrants;

- The establishment of a national AIDS memorial that acknowledges the impact of HIV and AIDS, honours and remembers those who we have lost;

- Taking a leading role in tackling violence and discrimination against LGBT+ people around the globe.

Without ascribing any judgement as to whether these are policies which government should or should not adopt, they are clearly demands of a political nature. Although the desire of those in policing to show solidarity with groups that have disproportionately experienced unlawful discrimination may well be understandable (particularly given this has at times been due to police actions), the need to demonstrate political impartiality is of greater importance. It cannot be appropriate for police officers in uniform, with the over-riding need to demonstrate political impartiality, to be part of a march which has, as a central feature, the making of political demands.

It is worth noting that it is not only the National LGBT+ Police Network who have sought for police officers to take part in Pride events. The National Police Chiefs’ Council stated in 2022 that, “Taking part in Pride is important for LGBTQ+ colleagues within policing. It allows LGBTQ+ people to see that they are represented in the police service and it is an excellent public engagement opportunity where we can promote safety messages, understand community concerns and recruit from diverse communities”.98Guardian Website, 30th June 2022, last accessed 12th December 2022, link Two years previously, during the coronavirus pandemic, the national police lead for LGBT+ issues, similarly encouraged “supervisors and senior managers to support their LGBT+ staff to be part of the virtual Prides, just as we would normally”.99National Police Chiefs Council Website, last accessed 12th December 2022, link Given the encouragement of senior police officers, it is perhaps unsurprising that Staff Networks are following their lead and seeking to actively participate in Pride marches, despite their clearly political nature.

The National LGBT+ Police Network’s website is hosted at the address https://lgbt.police.uk/. The usage of the police.uk web domain is restricted to those approved through the College of Policing by the chief police officer who is the relevant national ‘Portfolio Lead’ for that area.100College of Policing Freedom of Information Request Response, Ref: FOIA-2022-128, 3rd January 2023 A number of the articles hosted on the National LGBT+ Police Network’s website raise questions as to whether they are appropriate for serving officers to have written for publication on an official police website.

A blog published in February 2021 and written by a serving Police Sergeant describing the meaning of the ‘Rainbow Flag’ and its development in recent years states,

“It [The ‘Rainbow Flag’] also includes the white, blue and pink chevron for transgender people. It has been widely adopted recently due to the international focus on Black Lives Matter protests and vitriol in the UK press about Trans lives fuelled by comments made by J K Rowling.”101National LGBT+ Police Network Website, 15th February 2021, last accessed 13th December 2022, link

That a serving police officer has been provided with a what is, in essence, an official police platform to make a claim that an individual, who has herself been the subject of a campaign of threats and abuse, has ‘fuelled vitriol’ in the press is at the very least remarkable.

The National LGBT+ Police Network website also provides a platform to support the campaigning organisation Stonewall Equality Ltd. One example of this is the Network’s website publishing information in September 2020 concerning the Stonewall ‘Trans Rights are Human Rights’ campaign where elements of the campaign are highlighted including writing to the Prime Minister to call on the Government to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004.102National LGBT+ Police Network Website, 14th September 2020, last accessed 13th December 2022, link

The Network’s website also hosts the ‘Trans Guidance for the Policing Sector’ which appears to have been published by Stonewall and co-authored by representatives from Stonewall and Surrey Police.103Stonewall (undated), Trans Guidance for the Policing Sector: An Overview, link The introduction to the Guidance is authored by an Assistant Chief Constable who was previously the national lead for LGBT+ issues in policing. The Guidance contains various proposals relating to how police forces should approach employees who are transgender. This includes the proposal that when police officers or staff transition their gender their personal records should not refer to their previous name and that the individual should be marked as having left the force with a fresh record showing their new details.104Ibid. p. 6 It is unclear how this might affect the availability of police performance or misconduct records for individuals in such circumstances. The Guidance also suggests that individuals who ‘identify as gender-fluid may require two warrant cards to reflect their gender on different days’.105Ibid. p. 8 The impact on the security of individuals being issued with two warrant cards is similarly left unclear.

There is no doubt that amongst the membership of the National and force LGBT+ Police Networks there are many outstanding and courageous police officers. It is also clear that the Group’s membership is often seeking, through their work, to protect those who may be particularly vulnerable to becoming victims of crime. However, the Network’s practice of straying into political activity or inappropriate commentary cannot be permitted given the vital importance of the police service remaining impartial. The LGBT+ Police Network’s political activities, including their work with external campaigning organisations, should not continue.

The perception of impartiality is critical to maintaining the public’s confidence that policing is being done fairly. Even the perception that those in policing, with their coercive powers of arrest and detention, might attempt to influence political debate has the potential to be hugely damaging in a democracy. That is not to say that police officers should be prevented from offering professional contributions to private policy discussions, nor should there be an expectation of silence on settled ethical questions. However, where there are unresolved political questions, whether divided along party political lines or not, far greater care is required and there are clear examples of Staff Networks too often over-stepping what is appropriate.

Next chapter4. Conclusion & Recommendations

Police Staff Networks have grown significantly in number over the last twenty years. Existing in a broadly ungoverned space has enabled many Staff Networks to broaden their activities to those which are beyond the scope of what is appropriate for individuals working in policing.

It is time for policing and if necessary Government, to bring policing’s Staff Networks into a more structured and consistent framework. This approach would support everyone in policing to maintain a focus on those activities which contribute to the core mission of keeping the public safe, preventing crime and catching those who would commit crime and disorder in our communities.

At the very least Chief Constables, and if necessary Government, should:

- Bring every Staff Network under a consistent internal governance framework. This should include how each Network should be constituted, organised and run at a national and local level. It should be clear that Staff Networks are part of policing and not independent organisations. National Staff Networks should operate under the purview of the National Police Chiefs Council and force-level networks should operate under the purview of the local Chief Constable.

- Where Staff Networks have pre-existing independent arrangements as set out in statute (for example as charities, Community Interest Companies or Charitably Incorporated Organisations) they should be reconstituted to bring them into a consistent internal governance framework as part of policing. If these organisations are unwilling to do so, they should become truly independent with their members and executives no longer permitted to undertake activities in police duty time, they should not be permitted to use publicly funded police resources such as meeting spaces or IT, they should receive no funds from police budgets and the organisations should be treated as external stakeholders. In such circumstances an alternative Staff Network should be created which does operate within the internal governance framework.

- Every Staff Network should have as its primary objective to contribute to improving the effectiveness of policing on behalf of the wider public. It must be explicit that this must over-ride all other considerations.

- There should be full public transparency of how Staff Networks operate. This should include publishing committee memberships, minutes of meetings, workstreams, priorities and budgets.

- The amount of police duty time committed to Staff Network activities should be limited. The balance of every police officer’s and staff member’s work should be overwhelmingly focused on operational duties.

- Staff Networks should be bound by the requirements to remain politically impartial. Police officers and police groups must refrain from publicly lobbying on politically contested issues. This expectation should be made clear as part of the College of Policing’s Code of Ethics. Those who fail to follow these fundamental requirements of policing should be subject to appropriate disciplinary processes.

- Police managers must ensure that, when making policy decisions about both internal and operational matters, they act in the best interest of policing and the wider public. Managers must therefore not give inappropriate undue weight to the views of Staff Networks – an overarching requirement to act in the best interests of the public is paramount. Particular caution should be taken regarding proposals for external, politically active, organisations to deliver training or otherwise influence internal or operational policies.

Appendix: List of Police Staff Networks

National Networks106Based on those listed on the Joining the Police Website, last accessed 25th November 2022, link

British Association for Women in Policing

Christian Police Association

Disabled Police Association

Gypsy Roma Traveller Police Association

Jewish Police Association

National Association of Muslim Police

National Black Police Association

National LGBT+ Police Network

National Police Autism Association

National Police Pagan Association

National Sikh Police Association

Force Networks107The forces in Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Greater Manchester, North Yorkshire and Warwickshire do not appear to have listed their Staff Networks on their open-source websites

Avon and Somerset Constabulary

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

Disabled Police Association

LGBT+ Liaison Team

Police Pagan Association

Women’s Network

Bedfordshire Police

Diversity Support Group

Women of Colour in Policing

Cambridgeshire Constabulary

Christian Police Association

Disability Support Network

Fusion (Women)

Nexus (LGBT)

UNITY (all under-represented groups)

Cheshire Constabulary

Enable (Disability and Carers)

Encourage (Men’s Wellbeing)

Gypsy Roma Traveller Police Association

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender

Multi-Cultural Network

Veterans, Reservists, Cadet Instructors Network

Women In Policing

City of London Police

Association of Muslim Police

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

Disability Network

Health & Wellbeing Network

LGBT Network

Women’s Network

Cleveland Police

Armed Forces Network

Autism Association

Christian Police Association

Disability Support Network

LGBT+ Network

Support Association for Minority Ethnic staff

Vegan Network

Women’s Network

Cumbria Constabulary

Autism Support Group

Christian Police Association

Disability Support Group

Menopause Support Group

Multicultural Police Association

Pride Network (LGBT+)

Women’s Emergency and Public Services Support Group

Derbyshire Constabulary

Association of Muslim Police

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

enABLE (Disability)

Gender Equality Network

LGBT+ Support Network

Devon & Cornwall Police

Christian Police Association

Family Support Group

LGBTQ+ Network

Mental Wellbeing Network

Men’s Health Network

Neurodiversity Support Network

Women’s Network

Dorset Police

Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Support Network

Christian Police Association

Disability Support Network

LGBT+ Support Network

Neurodiversity Support Network

Women Inspire Network

Durham Constabulary

Autism Association

Disability Support Group

Ethnic Minority Support Association

LGBT+ Support Group

Menopause Awareness Group

STAR – Gender Equality Through Inclusion

Essex Police

Catholic Police Guild

Christian Police Association

Disability Network

LGBT Network

Menopause Support Group

Men’s Forum

Minority and Ethnic Support Association

Women’s Leadership and Development Forum

Gloucestershire Constabulary

Ability (Disability)

Christian Police Association

Ethnic Minority Association

LGBT+ Staff Support Network

Women’s Initiative Network

Humberside Police

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

Disabled Police Association

Gypsy, Roma, Traveller Police Association

Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual and Transgender Network

Pagan Police Association

Women’s Network

Kent Police

Armed Forces Network

Christian Police Association

Enable (Disability)

Kent Network of Women

LGBT+ Network

Race Equality Network

Lancashire Constabulary

Autism Network

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

Disability Network

European Staff Network

Inspire – Women in Policing

LGBT Network

Leicestershire Police

Adoption and Fostering Network

Association of Muslim Police

Christian Police Association

Black Police Association

Disability Support Network

Hindu Police Association

LGBT+ Network

Sikh Police Association

Women’s Inclusive Network

Lincolnshire Police

Christian Police Association

Menopause Group

Neurodiversity Network

Women’s Inclusive Network

Merseyside Police

Black and Asian Minority Ethnic Police Association

Catholic Police Guild

Christian Police Association

Disability Support Network

LGBT+ Network

Merseyside Parity 21 (Gender Equality)

Part-Time and Flexible Workers Network

Metropolitan Police Service

Association of Muslim Police

Association of Senior Women Officers

Police Christian Police Association

Black Police Association

Chinese and South East Asian Staff Association

Disability Staff Association

Emerald Society

Greek & Cypriot Association

Hindu Association

Humanists Association

Ibero-American Association

Italian Association

LGBT Network

Polish Association

Romanian Association

Sikh Association

Turkish Police Association

Norfolk Constabulary

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

LGBT+ Police Network

Reach Out (Disability)

Northamptonshire Police

Association of Muslim Police

Black Police Association

Christian Police Association

Disability and Carers Support Network

LGBT+ Network

Women’s Forum

Nottinghamshire Police