Authors

Content

Foreword

Nadhim Zahawi MP

Member of Parliament for Stratford-on-Avon

Former Secretary of State for Education

Throughout my tenure as Education Secretary, I put forward my vision for an education system that gives every child, regardless of their background, the best possible start in life. Such a system has to encourage schoolchildren to develop inquisitiveness and critical thinking skills. For this to be achieved, teachers need to embrace curiosity and criticism.

In order for this to be the case, there must be a culture free of fear and intimidation to explore and scrutinise ideas and beliefs. That is why I am greatly concerned that a new YouGov poll – commissioned by Policy Exchange – has revealed that a small but significant proportion of teachers in Britain are self-censoring to avoid causing offence on the grounds of religion, race, and gender or sexuality.

I was born in Baghdad, in Saddam’s Iraq, and grew up there until my parents fled when I was 11. At the age of 11, I sat at the back of my classroom in London, unable to utter a word of English. Thanks to my teachers, I began to understand, speak, read and write the language. I also began to think for myself. Unlike my schooling in Iraq, no topic was off limits.

As I have written before when arguing for blasphemy laws to be repealed, freedom of speech is not just a Western value – it is our common birth right as human beings.1Nadhim Zahawi, ‘Nadhim Zahawi MP: It’s time for the Islamic world to support free speech – and repeal blasphemy laws’, Conservative Home, 12 January 12, 2015, https://conservativehome.com/2015/01/12/nadhim-zahawi-mp-its-time-for-the-islamic-world-to-support-free-speech-and-repeal-blasphemy-laws/.

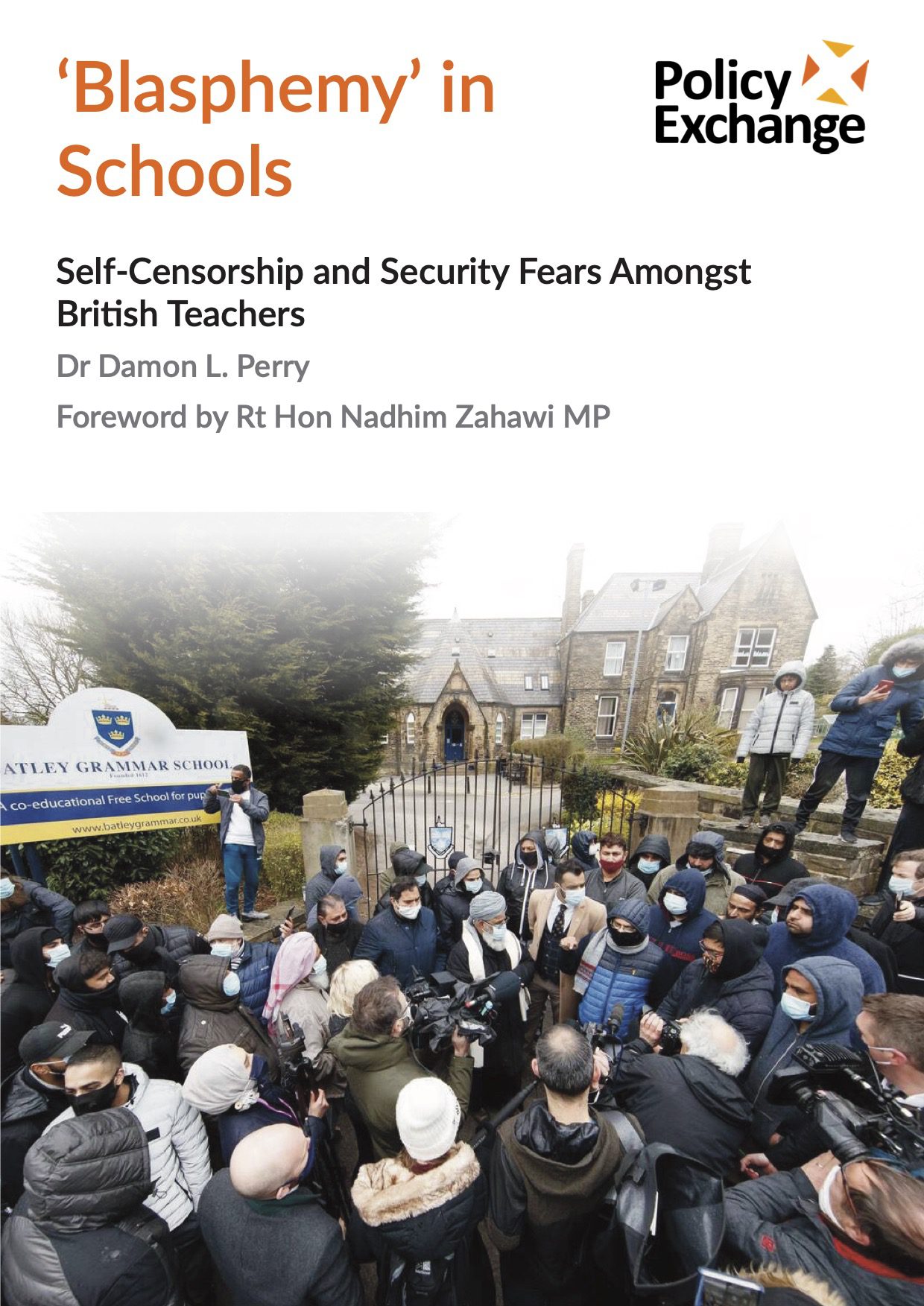

One factor in the self-censoring of teachers is undeniably a fear of losing one’s job – and even one’s life. Teachers in Britain remember the terrible fate of Samuel Paty in France, who was beheaded for showing a caricature of the Prophet Muhammad in a lesson highlighting the importance of freedom of speech. They also recall an incident closer to home: the teacher from Batley Grammar School who was forced into anonymity after showing a similar image in a lesson on blasphemy. The fact that he is still in hiding over two years later is a national disgrace.

The polling for Policy Exchange shows that around one in ten teachers are less likely to show an image of the Prophet Muhammad in lessons as a result of the Batley Grammar School protests. This is in addition to those – 55% overall, but rising to 64% of all art teachers – who would not use such an image anyway. These are not teachers who would show an image deliberately to offend anyone. The Batley Grammar School teacher had no intention of causing offence or distress – the image was shown as a visual aid to prompt an honest and necessary discussion about the acceptable limits of free expression. The teacher acted within the law.

It is, however, a sad and ironic consequence of activist bullying that in precisely the place where schoolchildren should be exposed to different and even potentially offensive ideas and images, the debate has closed down before it has even begun.

Of course, there is no need to expose pupils to offensive, satirical images gratuitously. But to display an image is not necessarily to endorse it; it is to reveal something about the world we live in. Context matters. We have laws against incitement to hatred; we do not need mobs outside school gates pressuring head teachers to fire teachers who are acting within the law and imposing de facto blasphemy laws in our country.

Thankfully, there are no blasphemy laws any more in Britain and we do not need them introduced by extremist mobs.

The negative influence of activist groups has been shown quite starkly by this poll: over half of all teachers think that there would be a risk to their physical safety if there were protests outside their schools led by activist groups. In the West Midlands, the proportion of teachers fearing this risk was around six in ten. These activists have somehow managed to persuade teachers and headteachers that all Muslims are offended by all images of the Prophet Muhammad. We actually have diverse traditions regarding the depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, but once again these activist groups – loud in their protests and easily offended – pretend to speak for all Muslims.

Teachers must not feel the need to self-censor out of fear. Headteachers, who set school policy, should not be bullied by de facto blasphemy codes.

But the evidence put forward in this report indicates that they would benefit from greater support from the Government. Proper national statuary guidance on the use of potentially offensive images and the freedom of expression would be a welcome thing – as recommended by this important and insightful report by Policy Exchange and as promised by the then Home Secretary back in March.

Our teachers – and their pupils – deserve better than this. We owe it to them to support them to provide a secure environment where open, honest and free discussion is not only permitted, but actively encouraged.

Next chapterIntroduction

In Britain, no one has the right not to be offended. Words or actions that are taken by some as offensive – whether they relate to religion, sexuality or race – are not criminal as long as they are not intentionally hostile and meant, or likely, to incite hatred. The statutory guidance on Non-Crime Hate Incidents, revised in March 2023, is consistent with the law in this regard. It states: “Fundamentally, offending someone is not, in and of itself, a criminal offence. To constitute an offence under hate crime legislation, the speech or behaviour in question must be threatening, abusive or insulting and be intended to, or likely to, stir up hatred”.2Statutory guidance, ‘Non-Crime Hate Incidents: Draft Code of Practice on the Recording and Retention of Personal Data (accessible)’, 16 March 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/non-crime-hate-incidents-draft-code-of-practice/non-crime-hate-incidents-draft-code-of-practice-on-the-recording-and-retention-of-personal-data-accessible.

Yet, this does not seem to be fully acknowledged in Britain’s schools. As this revealing survey of over a thousand teachers from YouGov and Policy Exchange demonstrates, since the Batley Grammar School protests, a small but significant proportion of British teachers have self-censored to avoid offence on religious grounds – 16%. (That proportion is slightly higher for teachers of certain subjects, including almost a fifth of all English teachers and art teachers – 19%). In areas with the largest Muslim populations, around 10% fewer teachers do not self-censor than those in areas with the smallest Muslim populations. A worrying proportion believe that – regardless of a teacher’s intentions – images of the prophet Muhammad should never be used in classrooms, even in the teaching of Islamic art or ethics: In addition to the 55% of teachers that would not personally use an image of Muhammad independently from the Batley Grammar School protests, an additional 9% said they personally were less likely to use it as a result of the events in Batley. The case of the teacher at Batley Grammar who went into hiding after death threats thus appears to have had a significant impact on teachers’ confidence and willingness to use materials that fall within the scope of the law.

Alarmingly, half of British teachers believe that if blasphemy-related protests led by activist and advocacy groups occur outside their schools, there would be a risk to their physical safety. Despite most teachers thinking that headteachers get the balance right – between supporting them to use materials that are on the right side of the law but which might offend, and ensuring no offence is caused – they are clearly in need of greater confidence in the support they can expect from their headteachers and, in the case of activist-led protests outside their school gates, the police.

Recent events have given further impetus to concerns regarding the physical safety of teachers and the security at schools. On 13 October, 2023, in Arras, France, a literature teacher, Dominque Bernard, was killed in a knife attack; the suspect, an Islamist extremist, was looking for teachers of history or geography.3Gabriel Joly, ‘“Il m’a demandé si j’étais professeur d’histoire”: un enseignant confronté à l’assaillant d’arras témoigne’, BFMTV, 13 October 2023, https://www.bfmtv.com/police-justice/il-m-a-demande-si-j-etais-professeur-d-histoire-un-enseignant-confronte-a-l-assaillant-d-arras-temoigne_AV-202310130575.html. The case has been compared to that of Samuel Paty, the teacher who was killed three years ago by an Islamist extremist for showing cartoons of Muhammad to a class on freedom of expression.4‘Hommage à Dominique Bernard et Samuel Paty : Gabriel Attal annonce “179 saisines du procureur de la République” après des incidents dans des écoles’, Le Monde, 17 October, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2023/10/17/hommage-a-dominique-bernard-et-samuel-paty-gabriel-attal-annonce-179-saisines-du-procureur-de-la-republique-apres-des-incidents-dans-des-ecoles_6195023_3224.html. Both teachers have been described by President Macron as champions of the values of the French republic. Although this tragic incident took place across the Channel, France’s battle with Islamist extremism is one shared with the UK.

Closer to home, in the wake of the Hamas terrorist attacks on hundreds of civilians in Israel on 7 October, protests on the streets of the UK against Israeli reprisals in the name of the Palestinian “resistance” have demonstrated alarming levels of hateful extremism and antisemitism.5Robin Simcox, ‘Hate marches in Britain are a wake-up call to all decent people’, The Times, 19 October 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/be0119e8-6dd6-11ee-b5d7-5487922f056f. Some Jewish schools were forced to close on 13 October, when Hamas called for a “Global Day of Jihad”, and several Jewish schools were vandalised with red paint.6Ibid. See also: Ali Mitib, Matt Dathan, and Chris Smyth, ‘Jewish schools in north London vandalised with red paint’, The Times, 17 October 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/jewish-schools-in-north-london-vandalised-with-red-paint-gsgw3fzxs. The atmosphere has been fraught. The Department for Education wrote to school leaders “to ensure that any political activity from pupils in response to the crisis does not create an ‘atmosphere of intimidation’”.7‘Israel-Hamas conflict: Ministers urge “sensitivity” in schools’, TES Magazine, 18 October 2023, https://www.tes.com/magazine/news/general/israel-hamas-conflict-dfe-ministers-urge-sensitivity-schools.

As this report argues, support for schools – whether in the context of these broader political currents or not – should include clearer and firmer guidance in the event of blasphemy-related incidents. This guidance was promised by the then Home Secretary in the wake of the Kettlethorpe School “Quran incident” in February this year, when a 14-year old autistic student was suspended from school and sent death threats from other students for scuffing a copy of the Quran, which he had brought into school as a forfeit for losing a video game amongst friends. But the Department for Education has said existing guidance is adequate,8Samantha Booth, ‘DfE snubs Braverman pledge for new blasphemy guidance’, Schools Week, 9 March 2023, https://schoolsweek.co.uk/dfe-snubs-braverman-pledge-for-new-blasphemy-guidance/. and in a written statement the Home Office has suggested such guidance is not being developed.9‘Schools: Blasphemy’, Question for Home Office, UIN HL6624, UK Parliament website, 20 March 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-03-20/HL6624/. According to this poll, 40% of teachers say that their schools do not have any guidance for teachers on avoiding offence to religious or community groups from teaching materials or lesson content. This means that many schools lack a code of practice for dealing with blasphemy-related incidents and similar situations where unintentional offence caused by teachers or the use of certain teaching materials may lead to protests and even violence. Schools should not be left to their own devices; there should be national statutory guidance on these matters, since they potentially involve security risks to individuals that we should not take lightly.

In April 2023, Lord Sharpe, Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Home Office, said that “the Government has been repeatedly clear that there is no blasphemy law in Great Britain” and, as such, there are no plans to produce guidance for blasphemy-related incidents.10Ibid. The then Schools Minister Nick Gibb said the same thing after the events at Kettlethorpe School. Indeed, blasphemy is no longer a crime in England, Scotland and Wales. And that is a good thing. But the kind of blasphemy that is a concern today is not some outdated transgression against Christianity – as blasphemy was defined in English law until 2008. It is, rather, a perceived act of symbolic violence against Islam, which, in the eyes of those claiming blasphemy, may justify threats, and even violent acts of retribution.

It is not good enough to dismiss blasphemy as a crime of the past, when incidents such as those at Batley and Wakefield have over the last decade become increasingly frequent. Last year, in 2022, the Shia-produced film, ‘Lady of Heaven’, caused protests around the country from Sunni Muslims unhappy with the film’s portrayal of the prophet Muhammad. Several cinema chains cancelled their planned screenings of the film. In the same year, a teacher was suspended after photos of him holding a ‘Jesus and Mo’ mug appeared online. In 2021, in addition to the Batley protests, the Christian convert Hatun Tash was stabbed at Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park for wearing a Charlie Hebdo T-shirt. In 2016, Ahmadi shopkeeper Asad Shah was murdered by Tanveer Ahmed for Shah’s alleged disrespect of Muhammad by claiming to be a prophet himself. In 2012, the producer of a Channel 4 documentary that questioned the orthodox Islamic account of the religion’s origins received threats. The programme has not been re-aired.

It is important that the British Government recognises that blasphemy does not need to be defined in the country’s current lawbooks or by any specific school of Islamic jurisprudence for some to resort to violence or issue death threats after taking offence to what they see as blasphemy against their religion or founding prophet. There has clearly been an increasing number of blasphemy-related incidents in Britain in recent years – including violence, threats or intimidation – as the timeline in this report demonstrates. Several of the most concerning of these incidents have taken place outside schools, where additional protests have occurred regarding the teaching of LGBT-inclusive education.

The polling in this report demonstrates that a significant number of teachers – who are self-censoring regarding the use of images of the prophet Muhammad – have been affected by the Batley Grammar School protests. It also suggests that teachers would benefit from firm statutory national guidance from the Government that makes clear that no one has the right not to be offended, and that schools have both a moral and legal obligation to protect teachers’ freedom of expression, as long as it is lawful, as well as their physical safety.

Next chapterKey Findings & Recommendations

Key findings

In March, 2023, YouGov conducted an online survey of 1,132 teachers from around the country. The key findings of the survey include a widely shared view amongst teachers that protests outside schools, particularly involving activist groups, present a risk to teachers’ physical safety; an admission from a significant minority of teachers that they self-censor to avoid causing offence (held most commonly by English and art teachers); a view held by over half of all teachers that they would not use an image of Muhammad even if it did not break any laws (e.g., incitement to hatred); and that around four out of ten schools have no guidance for teachers relating to situations in which what they teach or the materials they use may cause offence.

Protests and physical safety

The vast majority of teachers – three quarters (75%) – thought that if protests break out, they would be “damaging” to the teacher involved, with around four in ten (39%) indicating that they would be “very damaging”. More teachers in regions with the highest proportion of Muslims (45%) thought that the protests would be “very damaging” to the teacher than in regions with the lowest proportion of Muslims (34%). In Yorkshire and the Humber, where Batley is located, 60% of teachers said protests would be “very damaging” (in addition to 25% that said protests would be “fairly damaging”).

Alarmingly, half (50%) of all teachers thought that there would be a risk to the physical safety of a teacher accused of showing an offensive image if the protests were led by external advocacy groups or activists. In areas with the largest Muslim populations, 55% expressed such a view, and in areas with the smallest Muslim populations, that figure dropped to 40%. In the East Midlands, as many as six out of ten (60%) teachers indicated that there would be a risk to their physical safety in the event of activist-led protests. This view was shared by 59% of teachers in Yorkshire and the Humber, and 58% of teachers in the West Midlands.

Nationally, one in five (20%) indicated that there would be “a very big risk” to a teacher’s physical safety in such an event. In areas with the highest percentage of Muslims, one in four (25%) expressed such a view; in areas with the lowest percentage of Muslims, however, around one in eight teachers (13%) indicated as such. The region with the highest percentage of teachers indicating a “very big risk” was Yorkshire and the Humber, at 33%.

Thus, it is fair to say that a significant proportion of teachers believe that the participation of external groups in protests – rather than parents, governors, or students – pose the greatest risk to their physical safety. This concern is compounded by the view shared by a third of all teachers (33%) that external activists and advocacy groups would be the most likely source of protests.

Self-censorship

Only around 60% of teachers reported that since the Batley Grammar School protests, they have not self-censored with regards to materials that whilst not breaking any law might cause offence to religious groups. Significantly fewer teachers from parts of the country with the highest proportion of Muslims said they had not self-censored (57%) compared with teachers from parts of the country with the lowest proportion of Muslims (67%). These are both lower than we would expect in a society that values open and honest inquiry.

This does not mean that around 40% of teachers have self-censored. Nationwide, just 16% of teachers affirmed that they had self-censored – i.e., self-consciously refrained from teaching content or using materials that they otherwise would have taught or used – since the Batley Grammar School protests. But this is still a notable proportion of teachers, demonstrating the nationwide impact of the Batley protests and, it should be added, of the threats against the teacher involved. The number of self-censoring teachers could be even higher, since a further 24% – almost a quarter of all teachers surveyed – either could not remember or preferred not to answer.

When the figures are broken down by subjects taught, it is notable that almost a fifth of all teachers of English, art, and modern languages (19%) admitted to self-censor to avoid offence on religious grounds. Self-censorship was reported by similar proportions of teachers of history (18%), science (18%), citizenship (17%), geography (17%), and maths (17%).

It is worth noting that across all subjects, a similar proportion of teachers – around a fifth – reported that they had self-censored in relation to issues either of gender and sexuality (20%) or race (21%). This suggests that teachers’ fear of causing offence is not limited to matters of religion. Any future guidance to support schools on dealing with blasphemy-related incidents would thus best address all kinds of possible offence.

Use of images of Muhammad

Over half (55%) of all teachers said they would not use an image of Muhammad in the classroom, independently from the Batley Grammar School protests. For teachers of certain subjects, the figure was significantly higher: 64% of art teachers and 60% of citizenship teachers, for example, said they would not use an image of Muhammad. Such a significantly large proportion of teachers unwilling to use an image of a major religious figure – not just caricatures that are clearly mocking – surely demands an explanation. Is this out of fear or respect? If respect, how have so many teachers – including art teachers – arrived at the view that images of Muhammad are simply taboo in Islam, when there have been Islamic artistic traditions that both revere and depict Muhammad?11Christiane Gruber, associate professor and director of graduate studies at the University of Michigan, whose primary field of research is Islamic book art, paintings of the prophet Muhammad, and Islamic ascension texts and images, writes: “The Koran does not prohibit figural imagery. Rather, it castigates the worship of idols, which are understood as concrete embodiments of the polytheistic beliefs that Islam supplanted when it emerged as a purely monotheistic faith in the Arabian Peninsula during the seventh century.” Christiane Gruber, ‘The Koran Does Not Forbid Images of the Prophet’, Newsweek, 9 January 2015, https://www.newsweek.com/koran-does-not-forbid-images-prophet-298298. “The Islamic legal basis for banning images, including Muhammad’s, is less than straightforward and there are variations across denominations and legal schools,” writes Suleyman Dost, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam at Brandeis University. “It appears, for instance, that Shiite communities have been more accepting of visual representations for devotional purposes than Sunni ones. Pictures of Muhammad, Ali and other family members of the prophet have some circulation in the popular religious culture of Shiite-majority countries, such as Iran. Sunni Islam, on the other hand, has largely shunned religious iconography.” Suleyman Dost, ‘Muslims have visualized Prophet Muhammad in words and calligraphic art for centuries’, 24 November 2020, https://theconversation.com/muslims-have-visualized-prophet-muhammad-in-words-and-calligraphic-art-for-centuries-150053. Professor Hugh Goddard, director of the Alwaleed Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World in the University of Edinburgh, observes: “There isn’t unanimity [on the issue of depicting Muhammad] in either of the foundational sources – the Koran and the Hadiths. The later Muslim community has tended to have different views on this question as on others.” John McManus, ‘Have pictures of Muhammad always been forbidden?’, BBC News, 15 January 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30814555. See also Sameer Rahim, ‘Eye of the beholder – how the Prophet Muhammad has been depicted through the centuries’, Apollo Magazine, 18 December 2019, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/prophet-muhammad-depictions-art/, and Emma Graham-Harrison, ‘Drawing the prophet: Islam’s hidden history of Muhammad images’, The Guardian, 10 January 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/10/drawing-prophet-islam-muhammad-images. Where are these teachers learning about Islam and why are they not respecting the diversity of Muslim views on aniconism in Islam? Are they learning about Islam, directly or indirectly, through Islamist organisations? In addition to these teachers, an additional one in ten teachers (9%) said they were personally less likely to use an image of Muhammad as a result of the Batley protests. (The same proportion of art and citizenship teachers – 9% – said as much). This clearly shows a negative impact that the protests have had. For these teachers, at least, fear seems to be the motivating factor for self-censorship.

Teachers were also asked about the general acceptability of using an image of Muhammad in different educational settings. Significantly, more teachers expressed the view that images of Muhammad were generally unacceptable in formal displays in classrooms or assembly halls (51%) than other settings, such as in lessons in religious studies (35%), art history (32%), and ethics and freedom of speech (31%). Overall, this perhaps suggests an appreciation of a difference between using such images gratuitously and purposively. But that around a third of all teachers think it is generally unacceptable to use images of Muhammad for educational purposes in relevant subjects is a cause for concern.

Significantly, in areas of the country with the largest proportion of Muslims, 40% of teachers said it was generally unacceptable to use an image of Muhammad when teaching religious studies, but in areas of the country with the lowest proportion of Muslims, those sharing that view comprised just 28%. Furthermore, around four in ten (38%) art teachers stated that using an image of Muhammad is generally unacceptable when teaching topics such as Islamic art or art history, and 36% of citizenship teachers indicated that it is generally unacceptable to use such an image in lessons on ethics, political expression and freedom of speech.

School guidance

Only 36% of teachers said that their schools have issued guidance to avoid causing offence from teaching materials or lesson content. As many as four in ten teachers (40%) indicated that their schools do not have any such guidance. There is thus a significant lack of consistency amongst schools regarding whether or not they have guidance on managing possible offence. But the lack of national guidance from the DfE that specifically relates to managing blasphemy-related incidents suggests that even those schools that have guidance to avoid offence may lack consistency in approach and in the extent to which they prioritise freedom of expression.

The then Home Secretary’s promise in March of this year to work with the DfE to produce guidance “prioritis[ing] the physical safety of children over the hurt feelings of adults”12Suella Braverman, ‘We do not have blasphemy laws in Great Britain’, The Times, March 4 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/suella-braverman-we-do-not-have-blasphemy-laws-in-great-britain-9ps9lj8r5. was a welcome response to what has been recognised as a growing issue. But on 3 April, responding on behalf of the Home Office to a Parliamentary question regarding the matter, Lord Sharpe stated that there are “no plans to develop new blasphemy guidance for schools”.13‘Schools: Blasphemy’, Question for Home Office, UIN HL6624.

Headteacher support

Encouragingly, most teachers – 52% – thought that headteachers strike the right balance between supporting teachers who wish to use materials of their choice and preventing offence. Teachers in high Muslim population areas were only slightly more inclined than those in low Muslim population areas to indicate that headteachers could be more supportive of teachers who wish to use materials that (whilst legal) might cause offence (19% and 16% respectively). The greatest indication for headteachers to be more supportive of teachers to use such materials was in the East Midlands, at 27%.

The vast majority of teachers (86%) indicated support for headteachers’ commitment to protect a teacher’s identity in the event of protests about the use of materials deemed offensive by some groups. The majority of teachers (77%) also indicated that they support headteachers’ commitment not to automatically suspend teachers on the basis of their use of materials which some communities find offensive. Similarly, the majority (73%) supported headteachers’ commitment to uphold their freedom of expression, as long as it lies within the scope of the law, even if it unintentionally causes offence

Reporting possible extremism

Encouragingly, the Batley protests do not appear to had a negative impact on teachers’ willingness to report suspected cases of Islamist extremism to the police or safeguarding officers. Only 4% of teachers indicated that they were less likely to report suspected cases of Islamist extremism, whilst 8% indicated that they were more likely to report them. The majority of teachers (67%) indicated that they would report suspected cases of Islamist extremism regardless of the events at Batley Grammar School. Even more teachers (82%) indicated that they were equally likely to report potential cases of Islamist and Far-Right extremism.

Recommendations

- The Government should issue statutory guidance committing headteachers and schools to:

- uphold teachers’ freedom of expression, as long as it lies within the scope of the law, even if it unintentionally causes offence;

- do not automatically suspend teachers who have been accused of using materials which some religious groups or communities may find offensive, as long as they have been using this for a legitimate teaching objective;

- do not automatically suspend students who have been accused of causing offence or “desecrating” religious books; and

- protect a teacher’s identity in the event of protests about the use of materials deemed offensive by some groups.

- The statutory guidance should make clear that a school’s duty to teach fundamental British values does not in any way imply that teachers should be restricted from using materials that some people may find offensive. Contrary to what Batley Grammar School implied after its inquiry into the events of 2021, the promotion of “respect and tolerance between people of different faiths, beliefs and values”14Batley Multi Academy Trust, ‘Executive summary of the independent investigation commissioned by the Trust’, captured on 27 May 2021 at: https://web.archive.org/web/20210527122819/https:/batleymat.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/ExecutiveSummaryoftheIndependentInvestigationatBGS26052021.pdf. is perfectly compatible with supporting teachers using images of religious figures, whether satirical or historical, where there is educational value in the use of such images and where there are no threats or intentions to stir up hatred.

- Organisations that publicly name accused teachers on social media or through traditional media channels – thus potentially putting the physical safety of these teachers at risk – should be held accountable. The Government should consider what kind of action can and should be taken through the Charity Commission, or through criminal or civil court procedures, including prohibitory injunctions.

Background

Batley and Wakefield

In March 2021, a teacher was suspended from Batley Grammar School after showing a caricature of the prophet Muhammad in a religious studies class.15‘Prophet Muhammad cartoon sparks Batley Grammar School protest’, BBC News, 25 March 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-leeds-56524850. The image was taken from the satirical French magazine, Charlie Hebdo, whose offices were attacked in January 2015 by jihadist militants linked to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula; 12 people, including journalists and security staff, were killed in the attack prompted by the magazine’s publication of “blasphemous” cartoons of Muhammad. The teacher at Batley Grammar School, who ironically wished to educate his students about blasphemy, was suspended by the headteacher after a crowd of angry Muslim parents and external activists gathered outside the school.

The protestors, including people who did not have children at the school, saw the use of the image as blasphemous and called for the firing of the teacher. One protestor claimed the image offended “the whole Muslim community”.16Ibid. Rather than stand up for the right of the teacher to use materials with which he intended to generate a classroom discussion, the headteacher issued an “unequivocal” apology to the protestors and said that the use of the image was “totally inappropriate”.17Amelia Hill, ‘Batley cartoon row “hijacked by extremists on both sides”, says Warsi’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/mar/26/robert-jenrick-condemns-batley-school-protest-intimidation. An independent inquiry was commissioned by Batley Multi Academy Trust, which runs the school. The Department for Education did not commission its own inquiry. Some critics argued that by not intervening and by leaving the problem to be resolved at the local level – where the school’s own handling of the matter was not part of any investigation – the Government had ceded too much power to “outraged Muslim ‘community leaders’”.18National Secular Society Bulletin, Issue 78, Summer 2021, p.7, https://www.secularism.org.uk/uploads/3885-nss-bulletin-78-summer-2021-web.pdf. In May 2021, the Trust published the executive summary of its investigation, which concluded that the topics of the lesson “could have been effectively addressed in other ways and without using the image”, but affirmed that the teacher did not use the image with the intention of causing offence.19Batley Multi Academy Trust, ‘Executive summary of the independent investigation commissioned by the Trust’. The Trust said it “will not avoid addressing challenging subject matter in its classrooms”, but – appearing to undermine this pledge – it also said “it is committed to ensuring that offence is not caused”.20Ibid., emphasis added. The Trust justified its commitment to ensure no offence is caused – criticised by some as a “a route to censorship”21Camilla Turner, ‘Batley Grammar teacher allowed back to school but Prophet Mohammed picture should not be used again’, The Telegraph, 26 May 2021, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/05/26/batley-grammar-teacher-allowed-back-school-prophet-mohammed/. – in the language of “fundamental British values”. It stated:

Clearly, where subject content is sensitive or controversial, great care must be taken to ensure that lessons are planned and delivered in a way that promotes respect and tolerance between people of different faiths, beliefs and values.22Batley Multi Academy Trust, ‘Executive summary of the independent investigation commissioned by the Trust’.

The school then lifted the suspension of the teacher.23Nicola Woolcock, ‘Prophet cartoon row teacher can return to class’, The Times, 27 May 2021, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/prophet-cartoon-row-teacher-can-return-to-class-rs7bzt657. However, the teacher had been named on social media by a local charity, Purpose of Life, and had received death threats.24Charlotte Wace, ‘Prophet cartoon was shown at Batley Grammar School “a week before row”’, The Times, 3 April 2021, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/prophet-cartoon-was-shown-at-school-a-week-before-row-5sgwwdhdk. In October 2021, the Charity Commission formally rebuked Purpose of Life for “inflaming tensions” and outing the teacher,25Ewan Somerville, ‘Islamic charity that outed teacher in Batley cartoon row is rebuked by watchdog’, The Telegraph, 1 October 2021, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/10/01/islamic-charity-outed-teacher-batley-cartoon-row-formally-rebuked/. who fled his home under police protection and was given a new identity. The teacher’s father said that his son fears he will be murdered: “My son keeps breaking down crying and says that it’s all over for him. He is worried that he and his family are all going to be killed”.26Vivek Chaudhary, ‘EXCLUSIVE – “My son fears he will be murdered”: Father of blasphemy row RE teacher says he can never return to his old life after death threats over Prophet Muhammad lesson – and says school has thrown him under a bus’, Mail Online, 29 March 2021, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9414625/Teacher-tells-father-fears-life-Prophet-Muhammad-row.html. He also expressed anger at the way the school had treated his son:

The school has thrown my son under a bus. The lesson that he delivered in which the picture of the Prophet Muhammad was shown was part of the curriculum, it had been approved by the school …So why is my son being victimised like this? The school should have come out fighting for him and made it clear to the protestors that if offence was caused, then it was not my son’s fault.27Ibid.

Over two years later, the teacher remains in hiding after relocating with his family far from Batley.28Vivek Chaudary, ‘EXCLUSIVE: Teacher suspended after showing pupils a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed during RE lesson at West Yorkshire school nearly two years ago has a new identity but is STILL in hiding, his family reveals’, Mail Online, 7 March 2023, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11830621/Teacher-suspended-showing-pupils-cartoon-Prophet-Mohammed-hiding.html.

The danger to teachers accused of showing religiously offensive materials in the classroom from social media campaigns stoking a sense of grievance amongst Muslims became all too apparent in October 2020 in France. Samuel Paty, a secondary school history and geography teacher, was killed and decapitated by Chechen refugee, Abdullakh Anzorov, in a Paris suburb after showing an image of the prophet Muhammad – also from Charlie Hebdo – during a moral and civic education class discussion about freedom of speech.29Kim Willsher, ‘Teacher decapitated in Paris named as Samuel Paty, 47’, The Guardian, 17 October 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/17/teacher-decapitated-in-paris-named-as-samuel-paty-47. There is no doubt that the Batley Grammar School teacher had Paty’s fate in mind when he went into hiding.30Vivek Chaudhary, ‘EXCLUSIVE – “My son fears he will be murdered”: Father of blasphemy row RE teacher says he can never return to his old life after death threats over Prophet Muhammad lesson – and says school has thrown him under a bus’. Anzorov had sought out Paty, paying some students to identify him outside the school, after the father of a girl in Paty’s class launched a social media campaign naming Paty, as well as the school in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, and demanding his sacking.

Following the gruesome murder, President Macron visited the scene of the attack, and on the first anniversary of the event, in October 2021, he delivered a speech paying national tribute to Paty. He said Paty was murdered precisely because he embodied the values of the Republic, such as the freedom of expression: “Samuel Paty was killed,” he said, “because Islamists want our future and because they know that with quiet heroes like him, they will never have it.”31‘National tribute to the memory of Samuel Paty – Speech by Emmanuel Macron, President of the Republic, at the Sorbonne’, Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères website, 21 October 2020, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/human-rights/freedom-of-religion-or-belief/article/national-tribute-to-the-memory-of-samuel-paty-speech-by-emmanuel-macron. The case of Paty was described by Gilles Kepel, Macron’s special envoy, as an example of the new threat of “atmospheric jihadism”.32‘New Threat: “Atmospheric Jihadism”’, Le Secrétariat Général du Comité Interministériel de Prévention de la Délinquance et de la Radicalisation (CIPDR) website, 30 April 2021, https://www.cipdr.gouv.fr/nouvelle-menace-le-jihadisme-datmosphere/.

Have the Batley Grammar School protests and the killing of Samuel Paty affected the way in which teachers in Britain teach? Are they less likely, as a result, to use certain teaching materials in classrooms out of fear of offending not just Muslim students but Muslim parents and external activists? How do teachers feel about the prospect of protests outside their schools in the event that a teacher is accused of offending Muslim sensibilities in the classroom? These are relevant questions two years after the Batley affair, and three years after Paty’s assassination, since these are not the only examples of unrest, intimidation or violence triggered by religious offence taken by some Muslims in Britain in relation to teaching in schools.

Most recently, in February 2023, in the West Yorkshire town of Wakefield, just ten miles from Batley, four boys were suspended from school following an incident involving a Quran. At Kettlethorpe High School, a 14-year-old boy ordered a copy of the Quran on Amazon and brought it into school as a forfeit for losing a video game, Call of Duty. The book was reportedly bandied about and slightly damaged when it was dropped in a corridor. It had a slight tear and some pages were lightly marked. Remarkably, the school called West Yorkshire Police to intervene. The police found that there had been only “minor damage” to the Quran and concluded that no crime had been committed. Nonetheless, they recorded the incident as a “non-crime hate incident”.33Ben Ellery and Steven Swinford, ‘Quran damaged at school recorded as “hate incident” by police’, The Times, 8 February 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/quran-wakefield-school-students-police-investigation-uk-2023-zrj5q75ck. The Times reported that according to police guidance, non-crime hate incidents are “any non-crime incident which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by a hostility or prejudice”. And although the headteacher of the school said there was no “malicious intent”, the boy and three others were suspended from school. It is unclear what offence according to the school’s rules, if any, the children had committed.

As with the Batley protests, social media played a role in agitating a sense of grievance amongst local activists. A Labour councillor, Usman Ali, in a now-deleted tweet, claimed the Quran had been “desecrated” – a point of view echoed by the media outlet 5Pillars34‘The truth about the Wakefield school Quran desecration’, 5Pillars, YouTube, 14 March 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOL8LQ_-Tmo. – and described the incident as a “serious provocative action” that “needs to be dealt with urgently by all the authorities, namely the police, the school and the local authority”.35Damo/@concretemilk, Twitter post, 27 February 2023, https://twitter.com/concretemilk/status/1630148866929459200. And once again, there were death threats. Other students reportedly threatened the boy with arson and beatings. There is no record of other students being disciplined, or of the police taking action against those issuing death threats. West Yorkshire Police merely spoke to a student making such threats. A police spokesperson said that a report was made “of a malicious communications offence in relation to threats being made to a child in connection with this incident. A suspect was identified, who was also a child, and they were given words of advice by an officer”.36Izzy Hawksworth, SWNS and Jasmine Norden, ‘Police statement as Wakefield schoolboy who “dropped a Quran” is sent death threats’, Yorkshire Live, 3 March 2023, https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/local-news/police-statement-wakefield-schoolboy-who-26379609.

A meeting was held in the Jamia Masjid Swafia mosque, chaired by the mosque’s imam, Hafiz Muhammad Mateen Anwar,37Several days after the meeting, The Telegraph reported that Anwar had previously “warned worshippers not to wish others a merry Christmas, described homosexuality as ‘barbaric’ and music as ‘toxic’, and also made sectarian remarks about more liberal followers of Islam”. See: Neil Johnston and Gabriella Swerling, ‘Koran row imam suggested Muslims could be punished for celebrating Christmas’, The Telegraph, 12 March 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/03/12/imam-discusses-punishing-muslims-celebrating-christmas/. and attended by the boy’s mother, police officers and headteacher of the school. The non-Muslim mother, wearing a hijab, nervously told the attendees that her boy is autistic, does not always realise what is socially appropriate or inappropriate, and did not intend to cause any offence.38‘Community Meeting in Relation to the Qur’an Incident’, Jamia Masjid Swafia, Facebook, 24 February 2023, https://www.facebook.com/masjidswafia/videos/220999650384772/. However, she also repeatedly acknowledged how “disrespectful” his actions had been and apologised on his behalf. Police Chief Inspector Andy Thornton nodded in agreement when Anwar told the attendees that Muslims will never tolerate disrespect of the Quran and will give their lives in its honour.39Ibid. At the meeting, independent councillor for Wakefield East, Akef Akbar, acknowledged the numerous death threats sent to the 14-year-old boy – who was so petrified that he had not eaten for days – but appeared to undermine the seriousness of such threats, describing them simply as a flaring of passions.40Ibid. He added that the boy’s mother had to report the threats to the police, but “to her credit” did not seek further action. “She only asks,” he added, “that her son is not harmed.”41Ibid.

The Home Office’s response

Writing in The Times on March 4, 2023, the then Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, expressed her “deep concern” about events in Wakefield and the broader issues it raised. She said:

The education sector and police have a duty to prioritise the physical safety of children over the hurt feelings of adults. Schools answer to pupils and parents. They do not have to answer to self-appointed community activists.42Suella Braverman, ‘We do not have blasphemy laws in Great Britain’.

She said she would work with the Department for Education to issue new guidance to ensure that schools understand this. She also stated that she would announce new guidance for police regarding the recording of ‘non-crime hate incidents’, to ensure they only record such incidents where it is “proportionate and absolutely necessary”.43Gabriella Swerling, ‘Home Secretary to crack down on police reporting of non-crime hate incidents’, The Telegraph, 5 March 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/03/05/home-secretary-crack-police-reporting-non-crime-hate-incidents/. Taking a firm stance against political and cultural “timidity” in the face of de facto blasphemy codes and their supporters, she asserted:

We do not have blasphemy laws in Great Britain, and must not be complicit in the attempts to impose them on this country. There is no right not to be offended. There is no legal obligation to be reverent towards any religion. The lodestar of our democracy is freedom of speech. Nobody can demand respect for their belief system, even if it is a religion.44Suella Braverman, ‘We do not have blasphemy laws in Great Britain’.

Less than two weeks later, on March 13, Braverman announced new statutory guidance for the police on the recording of ‘non-crime hate incidents’ to ensure police officers prioritise freedom of expression.45Home Office, ‘Police will prioritise freedom of speech under new hate incident guidance’, UK Government website, 13 March 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/police-will-prioritise-freedom-of-speech-under-new-hate-incident-guidance. Under the new draft code of practice, personal data may only be included in a non-crime hate incident record if the incident is clearly motivated by intentional hostility and where there is a real risk of significant harm or a criminal offence.46Home Office, Statutory guidance: ‘Non-Crime Hate Incidents: Draft Code of Practice on the Recording and Retention of Personal Data’, fn 21, UK Government website, 16 March 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/non-crime-hate-incidents-draft-code-of-practice/non-crime-hate-incidents-draft-code-of-practice-on-the-recording-and-retention-of-personal-data-accessible#fn:21.

After Braverman’s announcement that the Government would work with the Department for Education (DfE) to produce new guidance for schools to deal with blasphemy-related incidents, the DfE said it “do[es] not plan to issue additional guidance on managing blasphemy related incidents”, and instead referred to a range of existing guidance – on behaviour, exclusions and political impartiality – which help schools meet “the needs of their pupils and to manage and resolve concerns and complaints”.47Samantha Booth, ‘DfE snubs Braverman pledge for new blasphemy guidance’, Schools Week, 9 March 2023, https://schoolsweek.co.uk/dfe-snubs-braverman-pledge-for-new-blasphemy-guidance/.

On March 20, 2023, Lord Godson, the director of Policy Exchange, sought clarity on this matter and raised a question in the House of Lords. He asked “whether the new blasphemy guidance being developed by the Home Office will be legally binding upon schools”; he also asked how the Home Office is “planning to make schools aware of their new responsibilities under this guidance; and how it will be enforced”.48‘Schools: Blasphemy’, Question for Home Office, UIN HL6624, UK Parliament website, 20 March 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-03-20/HL6624/. On April 3, Lord Sharpe, Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Home Office, responded. He said:

In response to recent incidents, the Government has been repeatedly clear that there is no blasphemy law in Great Britain. There are currently no plans to develop new blasphemy guidance for schools.49Ibid.

On April 17, Lord Godson posed the same question but to the DfE. Eleven days afterwards, answering on behalf of the DfE, Baroness Barran reiterated Lord Sharpe’s words with some additional comments:

In response to recent incidents, the Government has been clear that there is no blasphemy law in the UK. The Department [for Education] has no plans to produce specific guidance on blasphemy for schools.

Head teachers are best placed to make the decisions on how to meet the needs of their pupils. In doing so, there are a range of considerations, supported by existing departmental guidance. This includes ensuring political impartiality and promoting respect and tolerance between people of different faiths and beliefs.50‘Schools: Blasphemy’, Question for Department for Education, UIN HL7123, UK Parliament website, 17 April 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-04-17/HL7123/.

This chimes with what the then Schools’ Minister Nick Gibb said after the Kettlethorpe School incident. He stated that there is no blasphemy law and that “schools should be promoting fundamental British values of the respect for rule of law, individual liberty and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs”.51Samantha Booth, ‘DfE snubs Braverman pledge for new blasphemy guidance’.

However, in her response to the Independent Review of Prevent published on 8 February 2023 – just prior to the Wakefield Quran incident – the Home Office indicated that the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) “will lead on tackling blasphemy-related incidents”. If neither the Home Office nor the DfE will take a lead with the development of the guidance for schools, perhaps the DLUHC will do so.

The Prevent Review

Just two weeks prior to the Kettlethorpe School incident,52‘Four Wakefield pupils suspended after Quran damaged at school’, BBC News, 24 February 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-leeds-64757799. blasphemy-related intimidation and violence was highlighted as a growing concern in the Independent Review of Prevent, authored by William Shawcross. The Review stated:

An area of particular importance requiring more attention is that of violence associated with accusations of blasphemy and apostasy. It is vital that Prevent proactively seeks to address this ideological threat, given the serious challenge it poses to our national culture of free speech – which must be fiercely protected – as well as to the safety of individuals and the public.53William Shawcross CVO, ‘Independent Review of Prevent’, HC 1072, February 2023, p.147. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1134986/Independent_Review_of_Prevent.pdf.

The Review noted the significance of the Batley Grammar School protests, stating that it is “precisely the type of challenge where Prevent should institute urgent additional resources”,54Ibid., pp.149-150. as well the murder of Asad Shah, an Ahmadi Muslim shopkeeper, by a Sunni Muslim admirer of a Pakistani cleric who founded an organisation defending Pakistan’s strict blasphemy laws. The Review also expressed concern about the connection between “narratives around blasphemy in the UK … to hard-line Pakistani clerics and/or the Khatme Nubuwwat movement”.55Ibid., p.148. Khatme Nubuwwat/Khatm-e-Nubuwwat (the full name of which, Majlis-e-Tahaffuz-e-Khatm-e-Nubuwwat, means ‘The Assembly to Protect the End of Prophethood’) is the name of a Barelvi organisation and movement in Pakistan that aims to protect the belief in the finality of the prophethood of Muhammad. It was established in 1950 after the creation of Pakistan and in response to the rise of the Ahmadiyya movement, which was founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad who claimed he was a prophet. In 2016, after the murder of Asad Shah, The Middle East Eye reported: “The Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) currently lists both the International Khatme-e-Nubuwwat Mission and Aalami Majlise Tahaffuze Khatme Nubuwwat – two anti-Ahmadiyya organisations linked to the Khatme Nubuwwat movement – as affiliates under ‘Local/Specialist’ on its website”. See: Alex MacDonald, ‘”An unrighteous cult”: Ahmadiyya face persecution in UK’, Middle East Eye, 7 April 2016, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/unrighteous-cult-ahmadiyya-face-persecution-uk. There are other examples of blasphemy-related intimidation and violence in Britain, including the protests against and cancellations of the 2022 Shia-produced film, ‘Lady of Heaven’, and the firebombing in 2008 of the home of the publisher of a novel, ‘The Jewel of Medina’, about one of Muhammad’s wives, (see timeline of ‘blasphemy’-related incidents below).

Notably, one of the Review’s 34 recommendations accepted by the Home Secretary was to:

Improve understanding of ‘blasphemy’ as part of the wider Islamist threat. The Homeland Security Group should conduct research into understanding and countering Islamist violence, incitement and intimidation linked to ‘blasphemy’. It should feed a strong pro-free speech narrative into counter-narrative and community project work.56William Shawcross CVO, ‘Independent Review of Prevent’, p.158.

The Home Office responded to the Independent Review of Prevent, stating:

We accept this recommendation and agree that with the worrying number of incidents such as the killing of Asad Shah, the attack on Sir Salman Rushdie, and the incident at a Batley school, there is more to be done to counter blasphemy-related violence. As the overall lead for religious hatred, DLUHC will lead on tackling blasphemy-related incidents and Prevent will focus on where this contributes to radicalisation or terrorism. We have requested that the CCE conduct research on violence associated with blasphemy. Once they complete this research, we will consider with DLUHC, the CCE and wider Prevent partners, how Prevent should adapt to address the challenge of blasphemy violence.57‘The response to the Independent Review of Prevent’, Home Office, 8 February 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-prevents-report-and-government-response/the-response-to-the-independent-review-of-prevent-accessible.

The Home Office-funded Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE) is leading a research project on blasphemy incidents in Britain. For the Government to tackle blasphemy-related intimidation and violence in the country, it will certainly be useful to map out the key actors disseminating blasphemy narratives, the methods they use, their sources of funding, their target audiences, and the environments in which they operate. Policy recommendations relating to combating blasphemy-related violence and intimidation are expected to follow from the CCE’s research in this area. Hopefully, DLUHC, as the governmental agency taking the lead on blasphemy-related incidents, will produce guidance that is relevant for schools as well as local authorities.

The Bloom Report

On April 26, 2023, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities published the Bloom Report, an independent review into “faith engagement”. Led by Colin Bloom, the review sought to understand “how best the government should engage with faith groups in England”. One of Bloom’s tasks was to look “at some aspects where harm might be caused through religious or faith-based practices and a review of the government’s role in tackling them”. Encouragingly, amongst its recommendations, Bloom’s report urged the Government to “investigate where existing legislation and policy are failing to prevent the crime of forced and coercive marriage”58Colin Bloom, ‘The Bloom Review: Does government “do God?”’, April 2023, p.23. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1152684/The_Bloom_Review.pdf. and to regulate “‘out-of-school settings’ which include faith-based settings operating below the current minimum threshold for registration”.59Ibid., pp.20, 24. However, disappointingly, the report failed to mention blasphemy-related incidents whatsoever. It is curious that a major review into the state’s relationship with religion failed to acknowledge the increasing frequency of events in which religious offence has given rise to murder, violence, threats of murder or violence, intimidation, and censorship.

The Bloom Report was a missed opportunity to understand the extent to which blasphemy-related intimidation and violence is a cultural phenomenon within certain communities: is it more prevalent in some rather than others? To what extent is it driven by overseas actors, such as groups Iran or Pakistan? How important are domestic Islamists, whose interests potentially transcend particular ethnic, sectarian and linguistic Muslim communities? Which activist groups have played the most significant role in organising protests against schools and other public institutions in the blasphemy-related incidents in recent years? These are all important questions. Perhaps the CCE’s research into blasphemy will help answer them.

Next chapterTimeline of ‘Blasphemy’-Related Incidents in Britain

The Batley Grammar School protests are one of a number of ‘blasphemy’-related incidents that have occurred in Britain since the Rushdie Affair in 1989, which “marked the start of a new kind of blasphemy code, imposed not by law but by intimidation and the threat of violence”.60Stephen Evans, ‘Britain’s de facto blasphemy law strikes again’, National Secular Society, 9 June 2022, https://www.secularism.org.uk/opinion/2022/06/britains-de-facto-blasphemy-law-strikes-again. Such incidents, as outlined below, have increased in frequency in recent years, particularly over the last decade or so. They are not characterised by a legal definition of blasphemy – there has not been a blasphemy law in England and Wales since 2008 and, even then, it was limited to Christianity. Neither are they characterised by a theological definition. Several of these incidents occurred abroad but had significant repercussions in Britain.

| 2023 | Kettlethorpe Quran incident

In February 2023, a 14-year-old boy brought a copy of the Quran into Kettlethorpe School in Wakefield. The book was slightly damaged after being mistreated by a group of pupils. The 14-year-old was temporarily suspended in the midst of a furore agitated by false claims on social media that the book had been “desecrated”, burned and spat on. The school reported the matter to the police, who recorded it as a “non-crime hate incident”. The boy, who is autistic, received death threats from other students. His mother attended a public meeting in a mosque, apologising on his behalf. The meeting was chaired by an imam who said Muslims will die for the honour of the Quran. |

| 2022 | ‘Lady of Heaven’ protests and cancellations

In June 2022, the Shia-produced film, ‘Lady of Heaven’, was the subject of protests outside cinemas in Sheffield, Bolton, Birmingham and Bradford. The protestors, comprised of hundreds of Sunni Muslims, insisted that the film was “blasphemous” for its depiction of Muhammad and its negative portrayal of certain Muslim figures. The Muslim Council of Britain described the film as “divisive and sectarian”, adding, “There are some – including many of this film’s supporters or those engaging in sectarianism in their response – whose primary goal is to fuel hatred.”61MCB/@MuslimCouncil, Twitter post, June 6, 2022, https://twitter.com/MuslimCouncil/status/1533717565687619585. The film’s executive producer, Malik Shlibak said he had received death threats.62Nadia Khomami, ‘Sajid Javid attacks “cancel culture” as UK cinemas pull “blasphemous” film’, The Guardian, 8 June 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jun/08/sajid-javid-voices-cancel-culture-concerns-as-blasphemous-film-pulled-from-uk-cinemas. Cineworld pulled the film nationwide, to “ensure the safety” of its staff and patrons.63Helen Pidd, Jessica Murray and Andrew Pulver, ‘UK cinema chain cancels screenings of “blasphemous” film after protests’, The Guardian, 7 June 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jun/07/uk-cinema-chain-cancels-screenings-of-film-the-lady-of-heaven-after-protests. A smaller chain, Showcase, followed suit, and Vue Cinemas showed the film in selected branches.64Rory Tingle, Katie Feehan, David Pilditch, Gemma Parry, Jamie Phillips, and Matthew Lodge, ‘Showcase becomes latest chain to pull “blasphemous” Islamic history film The Lady Of Heaven from cinemas after furious backlash from Muslim protestors – but defiant Vue refuses to stop screenings’, Mail Online, 8 June 2022, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10896361/Showcase-latest-chain-pull-blasphemous-Islamic-history-film-Lady-Heaven.html. One of the protestors in Birmingham threatened “repercussions” to those who disrespected Muhammad, stating he and his fellow protestors would “lay our life on the line”.65Muslims Against Antisemitism (MAAS)/@MAAS_UK, Twitter post, 7 June 2022, https://twitter.com/MAAS_UK/status/1534243728096894977. |

| Teacher suspended for using a ‘Jesus and Mo’ mug

In March 2022, a teacher from Colchester Grammar School was suspended after images appeared online of the teacher holding a mug with an image from the cartoon series Jesus and Mo. A spokesman for the school said: “We have been notified that an image has been shared online of an individual appearing to use a cup that has an offensive image on it.”66‘Teacher at Colchester Grammar School in Essex suspended “for using mug with Prophet Muhammad image”’, ITV News, 30 March 2022, https://www.itv.com/news/anglia/2022-03-30/teacher-suspended-for-using-mug-with-prophet-muhammad-image. On the mug, in speech bubbles, a figure resembling Jesus with a crown of thorns says “Hey”, whilst another figure with a beard and a turban – Mo – replies: “How ya doin?”67Katie Weston, ‘Top grammar school suspends teacher after a photograph emerged of him holding a mug bearing an image of the Prophet Muhammad’, Mail Online, 30 March 2022, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10667917/Top-grammar-school-suspends-teacher-using-mug-featuring-image-Prophet-Muhammad.html. The cartoon’s website states that Mo is not really the prophet Muhammad, “it’s a body double”. Muhammad “couldn’t make it,” it says, “as he has been dead for centuries”.68‘About’, Jesus and Mo, undated, https://www.jesusandmo.net/about/. The Freethinker, a magazine established in 1881, said it will no longer publish Jesus and Mo cartoons because “in the current climate” and “being a small operation”, it had “no faith in the ability or willingness of the UK authorities to ensure that our right to freedom of speech is defended against extremists”.69Porcus Sapiens, ‘Free speech in Britain: a losing battle?’, The Free Thinker, 31 March 2022, https://freethinker.co.uk/2022/03/free-speech-in-britain-a-losing-battle/. |

|

| 2021 | Batley Grammar School affair

In March 2021, a teacher was suspended after showing a cartoon of Muhammad in a religious studies class on free speech. Protests by parents and activists outside the school, supported by a social media campaign, claimed he had insulted the founder of Islam and demanded his firing. The headteacher apologised “unequivocally”, saying that the use of the image was “totally inappropriate”.70Amelia Hill, ‘Batley cartoon row “hijacked by extremists on both sides”, says Warsi’, The Guardian, 26 March 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/mar/26/robert-jenrick-condemns-batley-school-protest-intimidation. An independent inquiry stated that the teacher did not intentionally use the image to cause offence. The school re-instated the teacher. But after being named by a Muslim-run charity, Purpose of Life, and receiving death threats, the teacher was relocated with his family, placed under police protection and given a new identity. Notably, the Muslim Council of Britain called for disciplinary action against the teacher if any further investigation found them “causing distress” to Muslims in the Batley Grammar School community whether intentionally or not.71The MCB tweeted: “Should any subsequent investigation find that the member of staff responsible for causing such distress to Muslim members of the Batley Grammar School community did so intentionally or recklessly, we trust appropriate disciplinary action will be taken.” See: MCB/@MuslimCouncil, Twitter post, 25 March 2021, https://twitter.com/MuslimCouncil/status/1375142257284747265. |

| Speakers’ Corner attack

In July 2021, a former Muslim and a convert to Christianity, Hatun Tash, was attacked with a knife at Speakers Corner in London. She was wearing a T-shirt in support of Charlie Hebdo magazine. The assailant escaped the scene, despite police officers being in pursuit, and has not since been caught. Media reports at the time suggested Counter Terrorism Command was leading the investigation.72Carly Mayberry, ‘Suspect Who Stabbed Christian Activist Multiple Times at London’s Speaker’s Corner Still At Large’, Newsweek, 28 July 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/suspect-who-stabbed-christian-activist-multiple-times-londons-speakers-corner-still-large-1614088. Tash had been arrested by the police at Speakers’ Corner earlier, in December 2020 and May 2021, for “breaching the peace”. On the latter occasion, she was confronted by a large group of Muslim men calling for her arrest for wearing a t-shirt with an image of Muhammad.73‘Police Brutality Vs Police Politeness | Speakers Corner’, DCCI Ministries, You Tube, 25 May 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MCQYheST8M8. The Metropolitan Police later sent a written apology74Letter from Metropolitan Police to Hatun Tash, Christian Concern, 29 September 2022, https://christianconcern.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Letter-of-Apology-Tash-6.10.22_Redacted.pdf. to Tash for the wrongful arrests and paid her £10,000 compensation.75Anugrah Kumar, ‘Christian evangelist awarded $11,000 for arrest; police apologize’, The Christian Post, 22 October 2022, https://www.christianpost.com/news/christian-evangelist-awarded-11000-for-arrest-police-apologize.html. In May 2023, Edward Little pleaded guilty to planning to kill Tash with a gun.76‘Speakers’ Corner: Man admits Hyde Park gun attack plot’, BBC News, 19 May 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-65646464. According to an encrypted chat on one of the phones he was arrested with, he had adopted the name “Abdullah” and had exchanged messages about religion and Iraq, whilst referring disparagingly to non-Muslims as “kuffar”.77‘Man pleads guilty to plotting gun attack at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park’, Sky News, 19 May 2023, https://news.sky.com/story/amp/man-pleads-guilty-to-plotting-gun-attack-at-speakers-corner-in-hyde-park-12884310. |

|

| 2020 | Killing of Samuel Paty

In October 2020, French schoolteacher Samuel Paty was murdered and decapitated outside the school in which he worked, the Collège du Bois d’Aulne, in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, France, by Abdullakh Anzorov, a Chechen immigrant. Paty had showed an image of the prophet Muhammad from Charlie Hebdo magazine in a moral and civic education lesson on freedom of speech. Anzorov had been alerted to Paty’s alleged transgression by a social media campaign against the teacher instigated by a parent of a student of the school. The student, whose complaints triggered the online campaign, later admitted that she lied about being in Paty’s class.78‘Samuel Paty: French schoolgirl admits lying about murdered teacher’, BBC News, 9 March 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56325254. In Britain, in May 2023, Ajmal Shahpal of Nottingham – who had posted an image of Paty’s severed head and praised Paty’s killer for being “as brave as a lion” – was found guilty of using social media to encourage people “to commit, prepare, or instigate acts of terrorism”.79Liam Barnes and PA news agency, ‘Man who praised Samuel Paty murder jailed for terrorism offences’, BBC News, 11 May, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-65561775. Shahpal had also posted messages saying that anyone who insulted Islam should be killed. Other messages threatened the French government. He was jailed for five-and-a-half years. |

| 2019 | ‘No Outsiders’ and anti-RSE protests

In February 2019, protests occurred outside Parkfield Community School in Birmingham over the No Outsiders programme, which teaches LGBT tolerance and equality. The protestors, predominantly Muslims, included parents but also external activists. Although not strictly blasphemy-related, the protests, which spread to other cities, were driven by the sentiment that the Relationships and Sex Education conflicts with orthodox Islamic values. The assistant head teacher of Parkfield who created No Outsiders80Sima Kotecha, ‘Assistant head “threatened” in LGBT teaching row’, BBC News, 7 February 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-47158357. and the head teacher of another school teaching LGBT equality both received threats.81Sima Kotecha, ‘Birmingham LGBT lessons: Head teacher threatened’, BBC News, 20 May 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-48339080. |

| 2016 | Gymnast Louis Smith’s mocking of Islam and death threats

In October 2016, Olympic gymnast Louis Smith and another gymnast, Luke Carson, appeared in a video online in which they made fun of Islam, pretending to pray whilst calling out “Allahu Akbar” (meaning God is the greatest).82Dan Sales, Patrick Gysin and Jason Johnson, ‘Has He Got A Screw Louis? Olympic ace Louis Smith accused of mocking Islam after yelling “Allahu Akbar” and pretending to pray in boozy video’, The Sun, 7 October 2016, https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/1934586/olympic-ace-louis-smith-accused-of-mocking-islam-after-yelling-allahu-akbar-and-pretending-to-pray-in-boozy-video/. Smith received death threats and issued an apology, recognising the “severity” of his mistake.83Stephen Evans, ‘The demonisation of Louis Smith: This is how a de facto blasphemy law works’, National Secular Society, 11 October 2016, https://www.secularism.org.uk/opinion/2016/10/the-demonisation-of-louis-smith-this-is-how-a-de-facto-blasphemy-law-works. |

| Asad Shah murder

In March 2016, shopkeeper Asad Shah, an Ahmadi Muslim, was stabbed and killed by Tanveer Ahmed in a premeditated attack. Ahmed, who drove from Bradford to Glasgow to carry out the attack, was incensed by Shah’s claim of being a prophet, and stated that Shah disrespected the prophet Muhammad by claiming so.84Simon Johnson, ‘Muslim shopkeeper Asad Shah had “disrespected Islam” according to man who admits his murder’, The Telegraph, 7 July 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/07/07/muslim-man-admits-murdering-shopkeeper-asad-shah-who-wished-belo/. Ahmed, who admitted to killing Shah, was jailed for life and will serve a minimum of 27 years in prison.85‘Asad Shah killing: “Disrespecting Islam” murderer jailed’, BBC News, 9 August 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-37021385. After Shah’s murder, the anti-Ahmadi group Khatm-e-Nubuwwat, which has an office in London, “congratulated all Muslims”.86‘Khatm-e-Nabuwat & Dawat-e-Islami linked to murder of Ahmadiyya Muslim Asad Shah’, Rabwah Times, April 6, 2016, https://www.rabwah.net/khatm-e-nabuwat-dawat-e-islami-linked-to-murder-of-ahmadiyya-muslim-asad-shah/. For a screenshot of the Facebook post, see: https://www.rabwah.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CefFC9zWsAIipX7.jpg. |

|

| 2015 | Charlie Hebdo jihadist massacre

In January 2015, 12 people were killed in a jihadist terror attack on the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris. The perpetrators, Said and Cherif Kouachi, claimed they were acting on behalf of Al-Qaeda to avenge the magazine’s publication of cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. Although this did not take place in Britain, a mentor of the Kouachi brothers, Djamel Beghal, was a “regular worshipper at London’s Finsbury Park mosque and a disciple of the radical preachers Abu Hamza and Abu Qatada”.87Josh Halliday, Duncan Gardham and Julian Borger, ‘Mentor of Charlie Hebdo gunmen has been UK-based’, The Guardian, 11 January 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/11/mentor-charlie-hebdo-gunmen-uk-based-djamel-beghal. See also: Matthieu Suc, ‘Charlie Hebdo : quand Chérif Kouachi rencontrait des djihadistes sur un terrain de foot’, Le Monde, 8 January 2015, https://www.lemonde.fr/police-justice/article/2015/01/08/charlie-hebdo-quand-cherif-kouachi-rencontrait-des-djihadistes-sur-un-terrain-de-foot_4552070_1653578.html. Beghal’s attendance of the mosque was when it was under the control of Abu Hamza.88Sean O’Neill, John Simpson, David Brown, ‘Charlie Hebdo killer was mentored by al Qaeda lieutenant’, The Times, January 8 2015, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/charlie-hebdo-killer-was-mentored-by-al-qaeda-lieutenant-cd5t96dftds. In a BBC/ComRes poll of British Muslims just after the massacre, 27% said they had some sympathy for the motives behind the Paris attacks; 24% disagreed with the statement that acts of violence against those who publish images of Muhammad can “never be justified”; and 11% agreed that organisations that publish images of Muhammad deserve to be attacked.89‘Most British Muslims “oppose Muhammad cartoons reprisals”’, BBC News, 25 February 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-31293196. For the full poll results see: BBC Today Programme British Muslims Poll tables, captured on 26 February 2015 at: https://web.archive.org/web/20150226184646/http:/comres.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/BBC-Today-Programme_British-Muslims-Poll_FINAL-Tables_Feb2015.pdf. On the first anniversary of the massacre, a motion was tabled in the House of Commons that recognised “the tragedy as an attack on the right of free speech”.90‘Anniversary of Charlie Hebdo Attack’, Early Day Motion 929, 7 January 2016, UK Parliament website, https://edm.parliament.uk/early-day-motion/48717/anniversary-of-charlie-hebdo-attack. |

| 2014 | Maajid Nawaz death threats

In January 2014, Maajid Nawaz, the co-founder of the Quilliam Foundation and a Liberal Democrat candidate for parliament, received abuse and death threats for tweeting a ‘Jesus and Mo’ cartoon. Nawaz wrote that his intention “was to defend my religion from those who have hijacked it just because they shout the loudest”; to “carve out a space to be heard without constantly fearing the blasphemy charge, on pain of death; and to “highlight that Muslims can engage in politics without insisting that our own religious values must trump all others’ concerns”.91Maajid Nawaz, ‘Why I’m speaking up for Islam against the loudmouths who have hijacked it’, The Guardian, 28 January 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jan/28/speaking-islam-loudmouths-hijacked. Mohammed Shafiq, a member of the Liberal Democrats Ethnic Minority group, called for Nawaz’s deselection from contesting the 2015 general election. Shafiq, also the CEO of the Ramadhan Foundation and then a presenter on Ummah Channel, tweeted about Nawaz: “We will notify all muslim [sic] organisations in the UK of his despicable behaviour and also notify Islamic countries.”92Mohammed Shafiq/@mshafiquk, Twitter post, January 18, 2014, https://twitter.com/mshafiquk/status/424575029599543296. For this, journalist Andrew Neil asked Shafiq in a television interview whether he was “organising a lynch mob”.93‘Cartoon row: Deselection call for Lib Dem Maajid Nawaz’, BBC News, 24 January 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-politics-25881508. Shafiq replied: “I think that’s quite offensive of you to suggest that … You can’t link anything to me that says I’ve advocated violence”. When Neil asked, for the second time, “What’s this got to do with other Islamic countries?”, Shafiq said, “It affects every Muslim around the world when a cartoon depicts the Holy Prophet”. He went on to state that Muslims find the depiction of Muhammad forbidden and offensive. |

| 2012 | ‘Innocence of Muslims’ protests

In September 2012, some 7,000 Muslims demonstrated outside the U.S. embassy in London over a short film uploaded onto YouTube called ‘Innocence of Muslims’, which they argued Muslims saw as blasphemous.94Jessica Elgot, ‘Muslims Call For Blasphemy Law In UK And UN To Prevent Repeat Of Anti-Mohammed YouTube Film’, The Huffington Post UK, 25 September 2012, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/09/25/muslims-blasphemy-law-uk-un-mohammed-youtube_n_1912004.html. The protests, which also took place outside Google’s office in London, were organised by the Muslim Action Forum.95Chris York, ‘Anti-Islam Film Protesters Rally Outside Google’s London Headquarters (video)’, The Huffington Post UK, 15 October 2012, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/10/15/anti-islam-film-protests-google-london-headquarters_n_1966081.html. |

| Islam Channel 4 documentary cancelled after threats