Authors

Content

Quotes

“I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

– James Carville, Chief Strategist to Bill Clinton (1994)

‘Stability is necessary for our future economic success. The British economy of the future must be built not on the shifting sands of boom and bust, but on the bedrock of prudent and wise economic management for the long term.’

– Gordon Brown (2000)

‘Being lectured by the president on fiscal responsibility is a little bit like Tony Soprano talking to me about law and order in this country’

– John Kerry (2004)

“What we need to do to establish the centre-right alternative, which consists of fiscal responsibility, financial responsibility and a balanced economy.”

– David Cameron (2008)

‘After a decade of profligacy, the American people are tired of politicians who talk the talk but don’t walk the walk when it comes to fiscal responsibility. It’s easy to get up in front of the cameras and rant against exploding deficits. What’s hard is actually getting deficits under control. But that’s what we must do.’

– Barack Obama (2010)

‘The most politically painless way to hand out goodies, without taking responsibility for their costs, is to pass a law saying that somebody else must provide those goodies at their expense, while the politicians take credit for generosity and compassion.’

– Thomas Sowell (2011)

Sound money and fiscal responsibility are the only secure foundations of a fair and strong economy.

– George Osborne, 2017

Next chapterIntroduction

It is easy to become distracted by the turmoil that has overtaken Westminster. What must not be forgotten is that underlying this is a severe economic crisis, that at this moment is directly impacting millions of people across the country. Charting a way through these difficult economic waters is the principal task awaiting our new Prime Minister.

Our country is deeply in debt, with a deficit that is viewed by the markets as being on an unsustainable path. Elements of this crisis are global in nature. Rising inflation and interest rates are happening across the world, as is the energy crisis precipitated by Putin’s war in Ukraine. Much, however, is home-grown. High spending during the pandemic had already put the national budget under strain. The mini-budget, however, and its fall out has undoubtedly made the situation worse. Significantly increasing borrowing, both for an indiscriminately generous energy package and unfunded tax cuts, with no credible plan to get debt back under control, has spooked the markets. Gilt yields rose sharply (though have since fallen back), the cost of the interest we pay on our debt has risen and market scrutiny of our finances has risen. The Government must now take greater steps to put debt back on to a sustainable path than would otherwise have been the case.

In this paper, Policy Exchange offers a range of options for the new Prime Minister. We recommend that they should impose a windfall tax on energy producers and, from April, significantly scale back the energy support package – as we first argued in September. Beyond that, there are choices. If the Government is prepared to tackle some of the biggest lines in the budget, such as ending the pensions triple-lock, rescoping major over-running public infrastructure projects or reducing the benefits received by wealthier individuals, then the pressure to make savings elsewhere will be less. If not, then more savings will need to be found from front-line public services – or else taxes will need to rise.

In order to consider these options properly, we welcome the fact that the new Prime Minister has delayed the fiscal event from 31 October to 17 November. This will enable a fuller consideration of the decisions that will shape the country over the following years.

Alongside this, investment in productive capacity such as transport, energy and skills, and regulatory changes that enable greater business investment and innovation, should be prioritised. It is essential that Government presses ahead with supply-side reforms, particularly in areas which are impacting the most on growth and household budgets such as housing and childcare. The mini-budget was right in one critical respect: the UK’s sluggish growth is the root cause of our underlying economic challenges. We do not underestimate the political challenges to implementing these reforms, but they are essential if we are to restore our long-term prosperity.

There are no easy answers. Our new Prime Minister faces difficult choices. They would be faced by any Prime Minister, of any party, taking office at this time.

There is no royal road to fiscal responsibility; no path to be taken that does not involve difficult, unpopular, decisions. Our purpose at Policy Exchange, in publishing this paper, is to outline some of the options available for restoring the economy back on to a sustainable path.

Next chapter1. Executive Summary

No Government can ignore the bond markets for ever.

The events of recent weeks, which have seen the yield of UK gilts rise to their highest in over a decade, a fall in the value of the pound, sharply rising mortgage rates and an unprecedented intervention by the Bank of England, in which it committed to buy up to £65bn of government bonds to stabilise the markets and protect pension funds, have brought this home in a way in which a decade of warnings have not. Unprecedented borrowing, first to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then as a response to the global energy crisis, have been compounded by a series of unfunded tax cuts. The turmoil created by this has already led to a succession of u-turns and the exit of first the Chancellor of the Exchequer and then the Prime Minister.

It is no surprise that governments are tempted by borrowing. Both increases to public services and tax cuts are in isolation – with a few notable exceptions – popular amongst the voters who will benefit from them. As Rt Hon Lord Peter Mandelson, writing for Policy Exchange in the foreword for McDonnellomics (Policy Exchange, 2019), observed, “The Conservatives, while condemning Labour’s tax and spend policies, are nonetheless turning on spending taps of their own.”1https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/McDonnellomics-How-Labour%E2%80%99s-economic-agenda-would-transform-the-UK.pdf The stagnation in UK productivity growth and real wages since the Great Recession has reduced the ability of the state to fund demands on the public purse through growth, leading to a steady rise in the proportion of GDP taken in tax and a greater incentive to borrow.

Nevertheless, responsible governments of all stripes have understood the imperative to work within a credible economic framework for managing the deficit, that took account of the wider economic and financial concept. From Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s pledge to match Conservative spending plans for the first two years after 19972http://www.labour-party.org.uk/manifestos/1997/1997-labour-manifesto.shtml, to David Cameron and George Osborne’s ‘Long-Term Economic Plan’3https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-governments-long-term-economic-plan/the-governments-long-term-economic-plan, a focus on responsible fiscal policy has rightly been at the heart of national decision-making for decades.

This does not mean there is no room for disagreement or debate: there were significant differences between Alistair Darling’s proposed approach to reducing the deficit and George Osborne’s. It is not always wrong to borrow: a national budget is more complex than a household one and, in a time of reduced demand and constrained liquidity such as the COVID pandemic, fiscal support is likely to be appropriate. Previous governments have recognised, however, the importance of doing so within a sensible credible framework, backed up by institutional credibility and stability, which ensured that any borrowing needed in the short term was not set on an unsustainable path. This is one of the principal reasons that governments have created mechanisms to help keep borrowing under control, including the introduction of ‘fiscal rules’, placing constraints upon government borrowing, and the creation of the Office for Budget Responsibility.

The fundamental diagnosis of the Truss government, that the trend rate of growth needs to improve, was correct. If growth rates had continued at their pre-2008 trend, the UK’s labour productivity would be about 18% higher today than it actually is in constant dollars, with commensurate gains to GDP and household income4https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/23031/documents/168790/default/. Spending on the public sector has increased, but too often in ways which do not improve public sector productivity or leave the general public feeling that they benefit from improved services. With the tax burden at its highest as a share of GDP since the 1950s, there is clearly room in the medium-term to reduce taxes, if this is done in a responsible way: as growth improves, spending on automatic stabilisers will decrease, and the structural deficit can be reduced if there are changes to the scope and size of the state or the way that public services are delivered. There there is a strong case for supply side measures to boost growth and productivity, particularly in highly supply-constrained sectors such as housing and childcare, as well as more broadly, where it is estimated the burden of regulation has increased costs on business by over £12bn since 2017.

A clear-sighted focus on growth is the only way to improve the UK’s medium-term prosperity. In the new Prime Minister’s Mais lecture, earlier this year he singled out capital investment, skills and innovation as fundamental to accelerating growth5“So in accelerating growth, I have three priorities. Priorities that I believe will foster a new culture of enterprise and deliver a higher growth rate. The first is to encourage greater levels of capital investment by our businesses. Second, we need to improve the technical skills of the tens of millions of people already in work. And third, we want to make this the most innovative economy in the world by driving up business investment in research and development.” The then Chancellor, Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, February 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/chancellor-rishi-sunaks-mais-lecture-2022. We endorse this position: as the Government sets out upon the essential task of bringing debt under control, it should do so through a lens that carefully assesses the implications of spending, cuts and regulatory reforms upon our future growth rates. Investment in productive capacity such as transport, energy and skills, or regulatory changes that enable greater business investment and innovation, should be prioritised, where possible, over spending that is not focused on building our economic capacity or regulations which stifle growth.

The mistake of the mini-budget, however, was to assume that higher growth could be obtained by throwing fiscal responsibility to the wind – and to fundamentally misread the broader economic conditions of high inflation, low unemployment and a global energy crisis. These are global challenges: inflation and interest rates are rising internationally and energy is a globally traded commodity. The global reversion towards a more historically normal interest rate environment after a period of low interest rates and quantitative easing would have been challenging in the best of circumstances.

There can be no doubt, however, that the mini-Budget has made the task harder, even following the reversal of most of its major measures. In borrowing costs alone, the rise in the yield of UK bonds means that the Government must potentially find an additional £10 billion per year to service the debt6https://ifs.org.uk/publications/ifs-green-budget-2022. The sharp rise in mortgage rates will damage consumer confidence and depress household spending. In addition, the political capital that has been spent will increase the difficulty of driving through serious supply-side reforms.

It is useless to argue, as some do, that the UK continues to have the second lowest debt to GDP ratio in the G7. The cost of borrowing does not depend on any one single metric, but upon overall expectations of inflation, future interest rate rises and creditworthiness. The wider circumstances around the recent fiscal event, including the failure to obtain an OBR forecast, or even a Treasury forecast; the dismissal of the Permanent Secretary of Her Majesty’s Treasury; the initial failure to consider spending controls or savings; the decision to adopt an energy package significantly more generous than that of comparator nations; and the subsequent briefing of further tax cuts to come have combined to do lasting damage. It is not the case that any of these in isolation are egregious – for example, there is a practical case for an expansive energy package, and a government must be able to dismiss senior officials in whom it has lost confidence – rather, the combination of all in concert proved fatal.

There is now an urgent imperative to get the public finances under control. The high political salience of the decision – now reversed – to abolish the 45p top rate of income tax in public debate temporarily obscured the fact that this represented only a small portion of the total additional fiscal widening added by the mini-budget. Ongoing market turmoil has forced significant further u-turns, with almost all tax cuts announced in the mini-budget now reversed, with the exception of the National Insurance Contributions and Stamp Duty relief. Corporation Tax will now rise to 25% as scheduled, income tax will remain at 20p indefinitely and various smaller measures, such as on the treatment of off-payroll working, have also been cancelled. These reversals, calculated as raising an additional £32bn7https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-brings-forward-further-medium-term-fiscal-plan-measures, are welcome, as is the decision to review after six months the Government’s overly expansive energy plan, one of the costliest in Europe.

These changes will not, however, be sufficient by themselves to get the public finances back on track. The new Prime Minister, faces a tremendously challenging series of choices. Even after the u-turns already made, there remains a predicted £25-30bn gap to have debt falling as a share of GDP within five years8Ibid. Furthermore, even if the Government sticks within the 2020 Spending Review settlement, the impact of inflation will mean a real terms reduction of £23bn in 2024-259Ibid. This must not just be top-sliced across all budgets: there are some forms of spending, such as research and development, infrastructure and other forms of capital investment, that can be beneficial to the growth outlook of an economy. Whether it is a Conservative Government seeking to lower taxes, a Labour Government, at some point in the future, seeking to invest more in front line services or a Government of any party seeking to lower the annual interest payments, finding efficiencies within public spending is essential.

At Policy Exchange our position is clear: both unfunded tax cuts, and unfunded spending, pose a potential threat to fiscal responsibility, and any borrowing must be accompanied by a detailed, credible and deliverable plan to show how debt will be kept on a sustainable path.

The Government should adopt a three-part approach to restoring the public finances. Firstly, it should adopt a set of measures on immediate taxing and spending, including proceeding with a significant retrenchment of its energy plan and imposing a temporary windfall tax on producers and generators; secondly, it should make a series of measured efficiency savings in public spending, while protecting front-line services as far as possible; and thirdly it must rapidly advance proposals to stimulate growth through supply-side reforms. Throughout, this should be done in a way which protects and enables the future drivers of growth. All of these should be embedded within a new, credible, fiscal framework that will ensure that all economic actors, including the markets, know how the public finances can be made sustainable over the cycle.

On taxation, welfare and the energy package, the Government should implement an immediate additional windfall tax on oil and gas producers, raising an additional £9-16bn, as well as proceeding with a large-scale public information campaign to assist in energy saving, saving £450m. To control the cost of the energy price guarantee, from April 2023 it should move to a tiered energy subsidy scheme, which would both be more progressive and would allow market mechanisms to increase the incentive for higher users to save energy, saving a further £12.9bn. The Government should continue to uprate both benefits and pensions by inflation, but should proactively tackle the cost of the welfare budget by reducing Universal Credit fraud to 2018-19 levels, saving up to £4bn – £5bn annually, and instigate a review of which benefits are taxable, including winter fuel allowance, disability living allowance and child benefit, to ensure wealthier individuals do not benefit disproportionately whilst removing cliff-edges in the tax system. Finally, on pensions, they should consider ending the triple-lock and instead link pensions to average earnings, saving £11bn in 2024-25.

The Government has choices as to the balance between the actions it takes on taxation, welfare and energy; and on public sector efficiencies. If it is unwilling to retrench significantly on the energy package, to levy a windfall tax or to address major outlays such as the triple-lock, it will need to make additional savings from public services.

On public sector efficiencies, even if no additional reductions are made to the 2020 Spending Review envelopes, the increase in inflation will necessitate real term cuts in departmental spending. The Government should not simply salami-slice by attributing these savings across the board, but instead actively prioritise to drive efficiencies, reduce spending on less effective programmes and protect spending on front-line service. We propose a non-exhaustive, indicative, menu of options that would collectively generate £20bn – £25bn of savings across the public sector. These potential measures include an immediate, rapid, re-assessment of all major transport projects, to assess whether each should be continued, rescoped or cancelled; reforming prescription charges, including by charging wealthier individuals who currently receive free prescription, raising £2-3bn annually; increasing NHS land-disposals to raise £3-6bn; a fourth wave of clinician-led reviews of NHS activity saving £1-2bn annually; cancelling one of the six new prisons, saving £500m; reprioritising at least £2.8bn within the schools budget from education support staff, back-office staff and educational consultancy to other priorities; saving £200m – £300m from the underperforming Multiply and traineeship programmes; saving £150m – £250m from non-growth orientated Higher Education funding and introducing a minimum entry requirement of EE for undergraduate degrees; saving £3.5bn from headcount reductions in the civil service and arm’s length bodies, including up to £1bn alone from merging DHSC and NHS England; reduce civil service consultancy spend by £1.3bn; as well as a number of smaller measures. We also recommend that we do not significantly increase the defence budget within this spending review period, including not moving to spend 3% of GDP until it has we are spending the money we currently allocate more effectively.

The Government need not make all of the savings set out in this section; however, the ongoing budget erosion being applied by inflation will mean that a significant number of efficiencies will need to be made, even if the Spending Review settlement is not reopened.

On the supply side, four of the areas with the greatest potential reform are planning, childcare, retained EU law and reducing business red tape. The proposed Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill offers an important opportunity to support the Government’s supply-side objectives outlined in the Growth Plan, but with 2006 pieces of retained EU law that remain unchanged, the Government must focus on the areas that will make the most difference, including financial services, DEFRA and planning. The House Builders Federation estimates that “at least 100,000 new homes across 74 Local Authorities are unable to proceed” due to requirements of retained EU law; the Government should also increase the building of Council housing, building at least 100,000 a year. Meanwhile, reforms to Solvency II could unlock up to an additional £95bn for infrastructure and real estate. By implementing a regulatory budget process overseen by the BEIS Secretary, Government should allocate each department a ‘regulatory budget reduction allocation’ and adopt a target of £15 billion in net regulatory savings for business over the next five-year cycle. Finally, childcare reforms to increase ratios and reduce the bureaucratic burden on childminders, as set out in the Policy Exchange paper Affordable Childcare (2022), would both assist households with the cost of living crisis and support parents back into the workforce.

Policy Exchange will be publishing further papers, exploring a number of the supply side issues in more depth, in the coming weeks. In an increasingly uncertain international environment, where economic shocks may be both more frequent and more severe, the supply-side reforms are essential. Increased growth – likely to include an economy that is rebalanced both sectorally and regionally, greater infrastructure investment and significant reforms in planning – is imperative if we are not to enter a period of perpetual austerity.

Overall, the scale of the structural deficit is too great to be met by any single measure alone – a combination of solutions are needed, alongside supply-side reform. A combination of measures, including implementing short-term revenue raising mechanisms such as an increased windfall tax, public spending efficiencies and significant supply-side reform must be implemented rapidly to place the public finances back upon a sustainable footing.

Next chapter2. Economic Background

The UK faces an acute short-term crisis and chronic long-term challenges. The short-term crisis is three-fold.

- An exogenous shock to the terms of trade driven by the war in Ukraine and rising energy and commodity prices.

- A tight labour market thanks to dislocations created during the pandemic, including a rise in long-term illness.

- A high degree of market volatility, including increased market concern over UK Government stability, which has resulted in rising gilt yields and higher interest rates than might otherwise have been the case. This has increased the cost of Government borrowing and will constrain Government action in the future.

The new Prime Minister will need to address these challenges head on. In the case of the terms of trade shock, the Government has intervened directly and comprehensively to reduce energy costs for consumers and businesses. Government has absorbed the cost of the exogenous shock, contributing to lower inflation in the short-term and protecting spending power now to prevent insolvency both in households and enterprises.

On the second point, however, Government has had to respond to a fast-changing situation in the markets, partly of their own making. While the global reversion towards a more historically normal interest rate environment after a period of low interest rates and quantitative easing would have been challenging in the best of circumstances, there is no doubt that the mini-budget has made the situation worse. While it is still to be debated whether the markets over-reacted or not to the original Growth Plan announcement, the market would have in all likelihood begun to price in higher interest rates as a result of the fiscal loosening at the heart of the Government’s new strategy. What was almost certainly not planned was a more than 100 basis point increase in the 30 year gilt yield.10Bloomberg UK. United Kingdom Rates and Bonds. 11 October 2022. Link. Furthermore, projections that the Bank of England’s policy rate would be 125 basis points higher by December this year and 175 basis points higher by Q2 2023 were also likely unexpected.11Fitch Ratings. Deeper UK Recession Now Likely as Interest Rates Rise Faster. 10 October 2022. Link.

The implications for the UK economy could be severe. Fast rising interest rates will dampen growth significantly. Moreover, interest rate and yield rises will make borrowing more costly. The most recent projection suggests that spending on debt interest will be £103 billion, £52 billion more than projected by the OBR in March of this year; it will be £18 billion in the year 2026-2027.12IFS. Outlook for the Public Finances. 11 October 2022. Link.

Some of the increased borrowing costs is a direct result of the quantum of fiscal loosening announced in the Growth Plan – borrowing was going to be higher as a result. However, the cost of servicing the debt is higher than it otherwise would be because of the market reaction. In this context, Government must take steps to regain market confidence and aim for a more gradual and less volatile rise in interest rates and yields.

This is not just for the sake of the public finances, but for the wider financial system as well. The abrupt rise in interest rates sparked by the Growth Plan has threatened defined benefit pension funds who employ liability driven investment strategies with insolvency. The hedges behind the LDI strategy have, thanks to the fall in the value of bonds, led to a potential ‘fire-sale’ dynamic, requiring Bank of England intervention. Government will have to take steps to stabilise the market, both for its own sake and for the wider financial sector.

To do so, Government must look at ways to reduce expenditure and increase revenue. Government has already announced reversals to some of the tax policies proposed in the Growth Plan, and they have floated the idea of a wider windfall tax. Alongside these measures, though, there will have to be some attempt at reducing expenditure. Relying simply on growth projections to forecast higher revenue have wide uncertainty and the markets may not find them credible. In that context, Government must be able to commit to fiscal decisions that reduce borrowing forecasts and give markets certainty about the future debt path of the state.

However, in taking steps to shore up the Government’s fiscal house, ministers must be cognisant of the long-term challenges facing the UK economy – low growth, low productivity and low investment.

The Growth Plan was right in one key respect – a path where greater state obligations are paid simply through a higher tax take are ultimately unsustainable. Stagnant economic growth has meant that less can be spent on public services, and a greater tax burden has to be levied to pay for those public services that are currently offered.

Low growth has been generated in part by low productivity. While many countries have struggled to restore the levels of growth seen before the Great Recession, in some key areas the UK has lagged some of its peers. In particular, in terms of output per hour worked, while most G7 countries have seen lower growth post-2008 than in the two decades before, the UK and the US have seen the greatest slowdowns, with productivity growth per hour in the UK over this period lagging Japan, Germany, France and Italy13ONS. International comparisons of UK productivity, final estimates, 2020. 20 January 2022. Link.. If the UK’s GDP per capita growth between 2008 and 2021 was repeated in this decade, the UK would become the poorest country in the Anglosphere by 2028.

Since 2008, the UK has had the second lowest productivity growth in the G7, ahead of only Italy. If productivity growth between 2008 and 2021 had been the same as between 1997 and 2008, UK workers would be producing $10.33 (£6.62) more per hour than they are currently.14OECD. GDP per hour worked. PPP 2015 USD. Link.

Actual vs Trend GDP Per Hour Worked, 2015 PPP, USD

Thanks in part to low productivity and low wage growth, UK households are now more than $7,000 poorer than their German counterparts.15OECD. Household Disposable Income. Link. There have been worries that the UK is becoming like East Germany, but in fact the regions of East Germany are now richer than most regions of the UK.16Imactivate using Eurostat data. Regional GDP explorer, indexed. Link.

Household Disposable Income, USD PPP

And amongst all this, the UK continues to face chronic investment challenges and regional inequalities. It is true that many of the challenges faced by the UK, including on planning and infrastructure, are not unique to us, with many developed countries grappling with how best to address them. Nevertheless, business investment in the UK continues to be the lowest as a proportion of GDP in the G7. UK institutional investors invest less in productive assets, like infrastructure and private equity than their international peers.17Thinking Ahead Institute. Global Pension Assets Study 2022. Link. In terms of investment on research and development, the UK is fifth in the G7 and at the bottom end of the OECD (though recent statistical reclassifications may impact this).18OECD. Gross domestic spending on R&D. Link. In terms of skills investment, the UK invests half the OECD average.19Sunak, Rishi. Mais Lecture. 24 February 2022. Link. Our cities outside of London underperform international peers substantially.20Swinney, Paul. So you want to level up? Centre for Cities. 17 June 2021. Link.

Investment as a Percentage of GDP

The Government thus has a significant challenge ahead of it: consolidating the public finances in ways that are not counterproductive to its growth strategy, and which will defeat the thrust of the plan in the first place. In that vein, this plan puts forward savings in areas where the economic impact is likely to be least negative, a set of supply-side reforms that could potentially have the strongest impact on growth, and a set of recommendations on reforming the state that will maximise efficiency both in terms of spending and in terms of effectiveness.

The new Prime Minister must signal to the markets that it has a plan to tackle the immediate credibility gap, while also playing the foundations for a better growth trajectory going forward. This Policy Exchange report aims to help Government fulfil this weighty endeavour.

Next chapter3. Taxation, the Energy Package and Welfare

The former Government’s Growth Plan announced over £200bn of unfunded spending decisions and tax cuts, including the largest (by share of GDP) energy support package in Europe. The size of this package, potentially when combined with a number of the aspects as to how the announcement was handled, has led to significant turmoil in the financial markets, a sharp rise in gilts and the need for the Bank of England to intervene to stabilise markets.

Market turmoil has since forced the Government to reverse the majority of the decisions announced in the mini-budget, with the exception of the National Insurance Contributions and Stamp Duty release. A number of smaller, pro-growth measures such as the £1 million Annual Investment Allowance, the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme and the Company Share Options Plan have also been retained, at least for now. Corporation Tax will now rise to 25% as scheduled, income tax will remain at 20p indefinitely and other measures such as on the treatment of off-payroll working and the freeze on alcohol duty have been cancelled. These reversals, calculated as raising an additional £32bn21https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-brings-forward-further-medium-term-fiscal-plan-measures, are welcome, as is the decision to review after six months the Government’s overly expansive energy plan, one of the costliest in Europe.

It is our view that the six-month review should deliver a significant retrenchment with regards to the size and generosity of the energy package, by shifting to a more progressive, more market-responsive tiered energy relief scheme and the extension of a windfall tax on oil and gas producers. Though this will not directly impact the structural deficit, it will reduce the increase in the stock of debt significantly (and thereby reduce interest payments). This will provide greater headspace to reassure the markets, and allow a combination of growth and efficiency savings to have debt falling as a percentage of GDP.

In the current economic climate and cost of living crisis, we believe that benefits should be uprated in line with inflation. It is not right to make the poorest in society bear the brunt of getting our public finances back in order. Nevertheless, pensions and benefits account for around a quarter of public spending and a serious consideration of where money can be saved is essential in order to moderate Government outlay and ensure that front line services are not asked to make disproportionate savings.

We have therefore set out four principal areas in which savings can be made, while continuing to uprate by inflation. Tackling fraud in Universal credit, where a reduction in fraud levels to 2018-19 levels would save £4.8bn annually by 2024-25; a review of the taxability of benefits received by wealthier individuals including winter fuel allowance and disability living allowance; reducing the number of people on incapacity benefit and moving from a triple lock to a double lock on pensions, which would save £bn annually by 2024/25.

3.1 Taxation

The Government has now reversed its decision on the majority of tax-cutting measures in the mini-budget, including on the top rate of tax, on corporation tax and on income tax. We welcome these decisions. While there should be a medium-term objective to reduce the burden of taxation as a proportion of GDP, this is not a justification for placing government borrowing upon an unsustainable path.

3.2 Energy

Reforms to the recently announced energy support programs provide some of the largest possibilities for stabilizing and improving the nation’s fiscal situation.

In response to global increase in energy prices driven by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there was an overwhelming need for Government measures to relieve the full cost of gas and electricity prices, which otherwise would have pushed millions of households and businesses into fuel poverty this winter. The intervention consists of several components, namely:

- Energy Price Guarantee (EPG): caps the unit price that (standard variable tariff) consumers pay for energy at 34p/kWh for electricity and 10.3p/kWh for natural gas, effective October 1st initially to last for two years, but now to be reviewed from April 2023. In addition, green levies will be transferred from bills onto the Treasury. This will see the average household pay an average of £2,500 per year, a savings of £1,000 versus the October price cap. Total cost: estimated £70bn to £140bn over two years22Counting the Costs: Forecasting the financial impacts of the Energy Price Guarantee on the UK government, 5 October 2022, Cornwall Insight: https://portal.cornwall-insight.com/s/blog-article/aCa8d00000003ijCAA/counting-the-costs.

- Energy Bill Support Scheme (EBSS): provides an additional £400 support payment for all households. Total cost: £11.6bn

- Energy Bill Relief Scheme (EBRS): concerning business and other non-domestic users, the scheme effectively freezes energy prices for six months, at £211/MWh for electricity and £75/MWh gas. A review conducted in three months’ time will determine the most vulnerable industries and how to support them after the scheme expires. Total cost: estimated £29bn to £44bn over six months.

- Energy Supplier Obligations: supporting households to insulate their homes with efficiency measures, including insulation coming into effect as of April. Total cost: £1bn over three years.

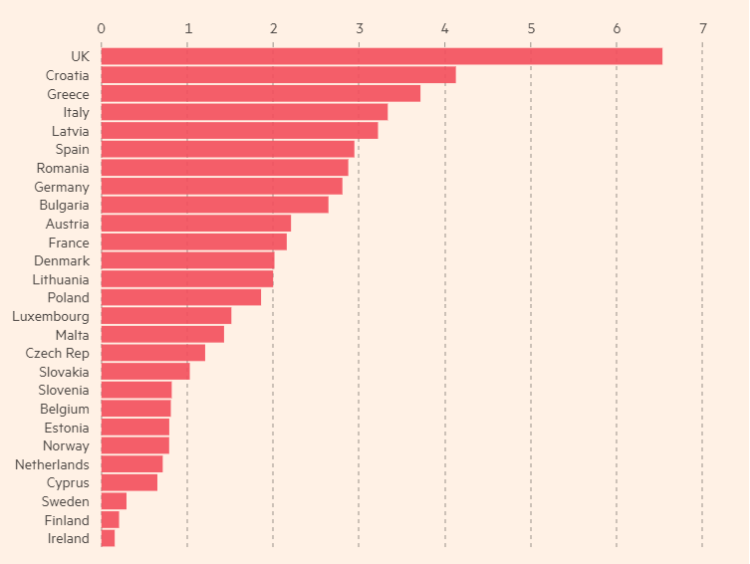

There are significant concerns with both the structure of the EPG and its messaging to the public. The level of support provided is significantly higher than most other countries in Europe, with a corresponding cost. For this reason, we welcome the commitment by the Government to renew it after six months, in order “to design a new approach that will cost the taxpayer significantly less than planned whilst ensuring enough support for those in need…and that the new approach will better incentivise energy efficiency.”23https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-brings-forward-further-medium-term-fiscal-plan-measures

State support for energy consumers as % of GDP

The EPG is also insensitive to market signals and reduces the incentive to conserve energy, even for the highest users. The Treasury incurs costs for every single unit of energy consumed and the natural price signal to encourage conservation is greatly distorted. These issues have been exacerbated by messaging on “the average household will pay no more than £2,500 this year”, creating the false impression amongst numerous families that their annual bill will be capped at that figure regardless of their total consumption. Regrettably, this misunderstanding has been repeated over media by senior political leaders, leading to further confusion.

The potential consequences of this misconception extend far beyond excess household energy bills. As explained by the National Grid, several factors outside of the Government’s control, namely abnormally cold temperatures or energy supply disruptions in Continental Europe, could force UK into controlled demand reductions or even uncontrolled blackouts this winter24UK winter blackouts warning if energy imports dry up, 6 October 2022, Emily Gosden, The Times: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/national-grid-uk-winter-blackouts-warning-7x9h2sp2t. To avoid this devasting and likely fatal scenario, every effort that is within the Government’s control must be undertaken to conserve domestic energy supplies, particularly during periods of peak demand. Fortunately, these measures could complement improvements to the fiscal situation.

Last month, Policy Exchange proposed a Tiered Energy Relief Scheme (TERS), providing heavier subsidies for low levels of household energy consumption that gradually taper off at higher levels of energy demand which are exposed to true market prices25A Plan for Household Energy Bills, 1 September 2022, Policy Exchange: https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/a-plan-for-household-energy-bills/. Such design is advantageous in limiting the Treasury’s liabilities, while simultaneously delivering a clear signal to reduce personal consumption levels at a time of international energy shortages.

At the review point in April 2023, Government should transition to a TERS or a similar, consumption-limited design. Costs for EPG will depend on wholesale gas prices and total demand, hence the wide range of Cornwall Insight’s forecast.

While a range of consumptions ratios are possible, we estimate that enacting a simplified tiered subsidy effective April 1st would relieve Treasury expenditures of £5.11bn on electricity and £7.87 bn on natural gas subsidies, a total saving of £12.98 bn for the subsequent 2023-2024 fiscal year. 26Under a simplified, single-tier structure whereby the first half of average household consumption would be subsided down to 75% of the EPG price. Further savings would be achieved under demand reductions.

For practical and political considerations, £3bn of savings should be aggressively re-invested into the Energy Supplier Obligations for household efficiency upgrades, effectively immediately. Proactive outreach must focus on the worst insulated homes liable to be most adversely affected by the new subsidy limits, to improve their heat retention by next winter. Further support should be delivered through another £3 billion of direct cash payments to the most vulnerable, rather than subsidizing (and thereby encouraging) energy consumption.

This program change should be couched in response to the high and growing threats of uncontrolled power outages this winter by launching a public information campaign encouraging energy conservation. This would focus on simple and practical measures, such as reducing flow-temperatures on boilers to 55 degrees and shifting laundry machine usage to late evening hours.

This information should be delivered through a well-funded national advertising campaign through social and traditional media, with messaging that emphasizes the temporary nature of the crisis and embraces the patriotic “war footing” rhetoric favoured by politicians. Empowering citizens to make sensible decisions about their personal energy consumption and save money is no more “nanny-state” than road signs advising of upcoming intersections. From the perspective of fiscal responsibility, the argument is undeniable. The contemplated £15 million invested in educating consumers on conservation could yield an estimate of savings of £152m from electricity and $310m from natural gas through reduced subsidies for the EPG for the remainder of this year27Academic consensus on efficacy of energy-saving information campaigns is highly inconclusive; studies demonstrate results ranging from negative effects to savings of 8% (see “Information campaigns for residential energy conservation”, Andor, Mark Andreas et al, Ruhr Economic Papers, NO. 871, December 2020). We conservatively presume a demand reduction of 2% for natural gas and 1% for electricity..

3.2.1 Energy: Windfall Tax

The former Government’s aversion to windfall taxes on power generators to fund the EPG is based on sound economic principles and business theory. Such measures are highly arbitrarily and distortive, an effective expropriation from those who invested in delivering the energy resources Britain so desperately needs. Most problematic is the corrosive effect on investor confidence, which will be critical in this sector to achieve both the near-term expansion of hydrocarbon production and the medium-term transition to net-zero power generation.

However, developments over recent weeks have changed this calculation. The nation’s weakened fiscal outlook and higher borrowing is now the greater challenge to financing our decarbonization agenda than the moral hazard of windfall taxes. Further, recognizing the severe socioeconomic threats posed by record energy prices, leading energy companies like Shell are accepting the need for enhanced taxation on their earnings to “protect the poorest.”28https://www.lbc.co.uk/news/uk/shell-boss-calls-on-government-to-introduce-windfall-tax-on-energy-companies-to/ Ultimately, democratic pressure and political realities must prevail over theory in supporting families over corporate profits, with a tremendous three quarters of voters being in favour. The EU having recently imposed a 33% rate on taxable surplus profits on fossil fuel companies, and raising an estimated €117bn from low-carbon producers, weakens the competitive arguments for abstaining.

The revenue potential is significant. The 25% “energy profits levy” introduced by Rishi Sunak in May was initially expected to raise £5bn from North Sea oil & gas operations this year, but has since been revised to an estimated £7.7bn (and up to £28bn by 2025/2026).29“Tax on energy profits to rake in £28bn as prices surge”, 23 September 2022, The Telegraph: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/09/23/tax-energy-profits-rake-28bn-prices-surge/ This is on top of the regular corporate tax of 40% they already pay, double that of most businesses. But even with an effective rate or 65%, Britain is still below the global average of 70% and well beneath Norway’s 78% rate of taxation.

Further, Treasury estimates for the next two years suggest that gas producers and electricity generators could earn excess profits of £102bn and £68bn, respectively, a total of £170bn30“UK Sees Up to £170 Billion Excess Profits for Energy Firms,” 30 August 2022, Bloomberg: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-30/uk-predicts-up-to-170-billion-excess-profits-for-energy-firms?leadSource=uverify%20wall. Preliminary estimates for industry analysts suggest a windfall tax on renewables alone could generate up to £14bn for the year, providing over £400 of support per household.31“Renewable energy giants face £14bn windfall tax”, 09 October 2022, The Times: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/renewable-energy-giants-face-14bn-windfall-tax-vw6m0xg9t Under these circumstances, the government must consider a change of policy direction, offering companies a carrot and stick approach.

As part of the energy intervention, the Department of Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) also launched the Energy Supply Taskforce to negotiate with domestic and international suppliers in bringing down wholesale prices, both natural gas and electricity. The prospect of a windfall tax must be leveraged to achieve the best deals for Britain.

In realising these revenue opportunities, some approaches are better than others. One model, the recently contemplated “Cost-Plus-Revenue Limit” on renewable generators and nuclear has elicited vocal concern from industry. Pending clarity on the operational details, analysts are concerned the scheme would have the same negative impact on investor confidence as a straightforward windfall tax, but with significantly greater complexity, a higher risk of permeance, and no deductions for making domestic investments.

Whatever their earlier reservations, evolving market conditions more than justify a change in the government’s position. A clean, time-limited windfall tax on applied across the board on extraordinary profits makes more sense, both for tax revenue generation and investment certainty.

As a negotiating strategy, electricity generators and gas suppliers that subscribe to a domestic pool price and new Contracts for Differences (CfDs) that reduces the near-term cost of each commodity could be offered a partial exemption from any windfall tax. Producers and generators that abstain from pooled pricing and choose to take full advantage of wholesale markets should be taxed accordingly. Pending these discussions, benchmarks of an additional £5bn to £10bn from gas producers and a new windfall tax worth £4bn to £6bn from electricity generators would be reasonable targets, for a total revenue generated of £9bn – £16bn.

3.3. Benefits

In the current economic climate and cost of living crisis, we believe that benefits should be uprated in line with inflation. It is not right to make the poorest in society bear the brunt of getting our public finances not in order. Nevertheless, pensions and benefits account for around a quarter of public spending32https://obr.uk/forecasts-in-depth/brief-guides-and-explainers/public-finances/ and a serious consideration of where money can be saved is essential in order to moderate Government outlay and ensure that front line services are not asked to make disproportionate savings.

3.3.1. Reducing Benefits Fraud

Fraud levels in Universal Credit have increased significantly, from 6% to 13% between 2019 and 2022. As a result of this, the amount lost to fraud overpayment increased from £3.0 billion to £7.6 billion.33DWP. Fraud and Error in the Benefits System FYE 2022 estimates. 26 May 2022. Link.,34DWP. Fraud and Error in the Benefit System 2018-2019. 9 May 2019. Link. More importantly, the rate of loss has more than doubled, from 1.6% to 3.5%.35Ibid. If the net rate of loss in 2022 had been the same as in 2018-2019, the tax payer would have recovered £4.1 billion.

Benefit Fraud Rates

Government should aim to reduce its net overpayment loss between 2022-2023 and 2024-2025 to 2018-2019 levels. Government has already made provision for increased powers and recruiting 1,400 additional staff.36DWP. Fighting Fraud in the Welfare System. CP 679. May 2022. Link. If the net rate of loss were to fall to 2019 levels, it would save nearly £4.5 billion in reviewed benefits37Benefits reviewed in FYE 2022 were Universal Credit; State Pension; Housing Benefit; Personal Independence Payment; Employment and Support Allowance; Disability Living Allowance; Attendance Allowance; Pension Credit; Carer’s Allowance; Jobseeker’s Allowance; Incapacity Benefit. Link. in 2023-2024, and £4.8 billion in 2024-2025.

Reducing fraud to pre-pandemic levels would in itself generate billions in savings for the Government, and Government should target returning to 2018-2019 net cost rates next year and maintain these levels over the parliament.

3.3.2. Review of the Taxability of Benefits

Another area for reform that the Government should examine closely in the coming months to find savings is in relation to the application of income tax to benefits. Currently there are a range of benefits not subject to income tax. Government should commit to reviewing whether it is appropriate to continue these income tax exemptions, or abolish certain benefits altogether for higher rate taxpayers.

For example, the Winter Fuel Payment is a poorly targeted subsidy to those over pension age, which does little on its own to address fuel poverty. A report from the Environment Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee (2009) found that taxing Winter Fuel Payments for those on the basic rate of income tax and ending entitlement for those on the higher rate would save around 10% of total Winter Fuel spend.38In Thurley et al. Winter Fuel Payments Update. House of Commons Library. Briefing Paper CBP-6019. 5 November 2019. Link. From 2023-2024, this would save £200 million in both 2023-2024 and 2024-2025.

Alongside, an examination of benefits, Government must consider further reviews of tax reliefs that currently exist and which distort the overall taxation system. Some key examples include Business Asset Disposal Relief (Entrepreneur’s Relief), which does little to encourage investment, but which does result in Government foregoing £2.4 billion a year relative to taxing at the full capital gains rate.39Miller, Helen and Smith, Kate. Low rates of capital gains tax on business income lead to large tax savings but do not boost investment. 21 October 2019. Indeed, reform of Capital Gains has been strongly supported by the Office of Tax Simplification,40Office of Tax Simplification. Capital Gains Tax review – first report: Simplifying by design. November 2020. Link. and Nigel Lawson has noted that there is “little economic different between income and capital gains”.41Lawson, Nigel. House of Commons Debate: Taxes on Capital. Hansard. 15 March 1988. Link.

Ways to simplify the tax system will not all raise revenue either. One of the most significant ‘kinks’ in the tax system currently relates to Tax-Free Childcare, which is withdrawn automatically at £100,000. This creates an effective 97% tax rate , meaning that an individual with two children earnings £123,700 is only £760 better off than someone earning £99,000.42Cunningham, Alistair. The loss of free childcare: a 97% marginal tax rate. 2022. Link. Another kink in the system relates to the High Income Child Benefit Charge, which starts getting clawed back Child Benefit once one parent earns more than £50,000. The Child Benefit is meant to support families, but the current charge structure means that a family with two parents earning £35,000 receives a full child benefit while another family where one parent earns £55,000 and the other £15,000 would lose half of their child benefit entitlement. Making child benefit taxable for higher rate tax payers, rather than simply withdrawing it, would reduce this distortion.

Simplifying the tax code is a supply-side measures that makes the state more efficient and ensures a minimal number of distortions within the current system. When applied to benefits, it also ensures that money is spent where it is most needed, generating savings. Government should commit to a full review of taxability of benefits to, in particular, promote efficiency and growth, focus spending on those who need it most and to remove inefficient and counter-productive cliff edges within the system.

3.3.3. PIP and DLA spending

The state of the labour market remains one of the economic challenges facing the UK. This is reflected in both the rise in workless Universal Credit claims and the rise in spending on Personal Independence Payments. The rise in Personal Independence Payment spending is particularly concerning because of the rigorous process by which these claims are made and the fact that the PIP indicates a disability or long-term ill health.

In their latest annual report, the Department projected that, since 2017, spending on Personal Independence Payments would rise from £8.6 billion om 2017-2018 to £22.5 billion in 2024-2025. While this increase is accounted for in part by the shift from Disability Living Allowance to Personal Independence Payment, DLA is predicted to decline from £9.4 billion to £5.8 billion in the same period.43DWP. Annual Report & Accounts 2021-2022. July 2022. Link.

Combined PIP and DLA spending in 2017-2018 gives figures of £18 billion in 2017-2018 and £28.4 billion in 2024-2025.

DLA and PIP Spending

This charts a steep increase in long term ill-health which has reached 2.46 million people, the highest number on record.44Institute for Employment Studies. Labour Market Statistics September 2022. Link. Indeed, the rise in economic inactivity generally is being driven by an increase in the number of long-term sick, with the number rising from January-March 2020 to May-July 2022 by more than 3 million.45ONS, Table INAC01: Economic Inactivity: People aged 16 to 64 by reasons for inactivity. 13 September 2022.

The number of PIP clearances has risen in tandem. 536,770 claims were lodged between January 2022 and July 2022, compared to 351,617 in that same period in 2021 and 424,730 claims in 2019.46DWP, State Xplore. PIP Clearances.

The same pattern holds for jobless benefits in the UK too. Workless claims remain the highest they have been since 2012.47ONS. Data Tables For: Labour Market Overview, UK: September 2022. 13 September 2022

Workless UC and Jobseeker Claimants

In short, the labour supply remains an acute problem for Government, both by increasing DWP annual managed expenditure and by putting further strain on the labour market more generally.

DWP should look closely at its employment support schemes which have not always delivered value for money. To quote a Public Accounts Committee report on the Government’s Kickstart scheme,

the Department has not monitored and does not know whether it is putting the right people onto Kickstart, why people who are not taking up Kickstart jobs are not doing so, or what employers are providing with the £1,500 employability support grants awarded for each young person taken on through the scheme.48House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. DWP Employment Support: Kickstart Scheme. 9 February 2022. Link.

One key problem for the Government’s programmes is that programmes like Kickstart and Restart were primarily focused on the long-term unemployed.49Jayanetti, Chaminda. UK government’s £2.9 billion job search scheme has put only 7% of participants in work to date. 5 June 2022. Link. However, the underlying problem now is around economic inactivity. Government should look to expand the Restart programme to those who have been signed off long-term sick and older workers who have become inactive. It should also in particular be linked up with those who have recently been awarded a PIP or other disability related payment, to ensure that these individuals get the support they need to maintain some form of work if they can.

3.4. Pensions: Link to Earnings not Inflation

The pensions triple lock has been a widely popular, but extremely costly Government policy. Increases in the state pension have significantly outstripped weekly earnings and mean that individuals in-work are now significantly more likely to report absolute low income than pensioners.

Between April 2010 and today, the value of the basic state pension for a single person has increased by 45%, while regular earnings have increased by 37%, and prices have increased by 35%.50ONS. Consumer price inflation time series. Monthly. April 2010-April 2022. Link. Pensioner poverty is now far less prevalent than it was in the 1990s, with only 14% of pensioners reporting absolute low income, compared to 19% of the general population.51House of Commons Library. Poverty in the UK: Statistics. 29 September 2022. Link.

Percentage of Pensioners on Absolute Low Income

Given the savings that need to be made in the current economic context, it would be unfair to impose the burden soley on those in the labour market, whose incomes have grown less sharply than pensioners and who would have faced the most significant economic dislocation during the pandemic. It is therefore reasonable for the Government to consider uprating pensions by earnings in the coming two years. By keeping pensions in line with earnings, the burden of the economic adjustment currently being experienced would also be shared more equally through generations.

Importantly, though, the Government could ensure that the poorest pensioners are supported by uprating Pension Credit by CPI. This way, the poorest pensioners would still receive an inflation-adjusted top-up. Moreover, Government could focus on ensuring that the 1.4 million pensioners who do not claim nearly £1.7 billion in Pension Credit access the support to which they are entitled.52DWP. Eligible Pensioners urged to claim Pension Credit to help with cost of living. 15 June 2022. Link.

Projected State Pension Spend

Projections based on assuming a 1.7% increase in pension population in 2023-2024 from ONS 2020 Interim National Population Projections, ONS figures for 5.5% earnings growth in May-July 2022, ONS Figures for 2023-2024 uprating 2024-2025 assumptions based on 1.8% increase in pensioner population, 2024-2025 inflation and earnings projections taken from Bank of England projections for earnings and inflation from the August Monetary Policy Report.

More broadly though, now is an opportunity to consider the role of pensions relative to earnings. When the DWP Select Committee examined this question in 2016, they argued that the Government should adopt a ‘smoothed earnings link’ – that is maintain the pension at a fixed level relative to overall earnings.

In 2021, the Basic State Pension (BSP) was approximately 18.9% of mean gross weekly earnings, the highest proportion is has been since the 1980s. The New State Pension (NSP) was, at £179.60, 24.7% of annual gross weekly earnings, just slightly lower than the peak state pension’s value relative to earnings (26% in 1979).53DWP Select Committee. Intergenerational Fairness. 2016. Link. These figures are in fact higher as a proportion of earnings than when the DWP Select Committee recommended moving to a smoothed earnings approach in 2016.54Ibid.

As such, Government could move to a model that ensures the pension closely tracks earnings over time, ensuring that as a proportion of total earnings the pension does not lose its value, and is maintained at a relatively high level by historic standards.

In terms of the savings that could be achieved over this parliament if the pension was linked to earnings, it would save £5 billion in 2023-2024 and nearly £11 billion in 2024-2025. In total, the saving would amount to £16 billion over the remainder of the Parliament.

Next chapter4. Public Sector Efficiencies

Tax as a share of GDP is at record levels. Yet despite this, there is a widespread view amongst the public that this investment is not being reflected in better public services. This is supported by performance metrics: whether in health, policing or the court system, delivery of core functions is frequently well below historical levels.

Accordingly, it is imperative that the public sector improves its efficiency – which must mean stopping doing some things, as well as doing other things better. Even if the Government sticks within the 2020 Spending Review settlement, the impact of inflation will mean a real terms reduction of £23bn in 2024-2555https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-10/Outlook%20for%20the%20public%20finances.pdf . Our view is that, in this scenario, the Government should not seek to simply maintain all budgets at their current level – an effective top-slicing of all budgets – but rather should actively identify savings and efficiencies, in order to allow some additional reinvestment in front line services such as the NHS, schools and policing.

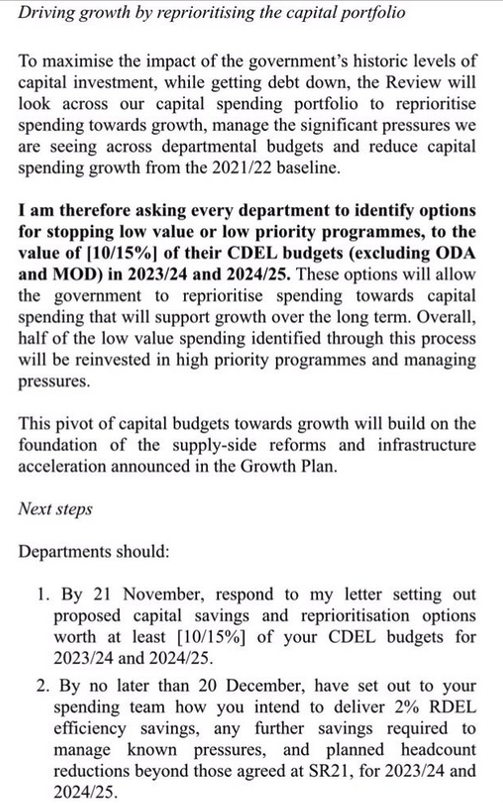

It has been suggested that the former Chancellor was intending to send a letter to all departments, seeking efficiencies of 2% of their Resource spending and 10-15% of their Capital spending (see extract of letter to right)56https://twitter.com/HarryYorke1/status/1581565640137052160?s=20&t=eGDb77abYVtHL2P4EDnmXw. It is possible that, after the leadership election, efficiencies at a higher level may be sought. Regardless of the precise amount, it is clear that any Government seeking to maintain fiscal responsibility must identify a number of efficiencies across all or most programmes.

In this chapter, we present a set of options for areas where efficiencies could be made. Some of these represent unnecessary or wasteful spending; however, other programmes have genuine benefits, but have been identified as lower priority programmes given the need to narrow the budget deficit without cutting front line services.

The Government has choices as to the balance between the actions it takes on taxation, welfare and energy; and on public sector efficiencies. If it is unwilling to retrench significantly on the energy package, to levy a windfall tax or to address major outlays such as the triple-lock, it will need to make additional savings from public services. Conversely, if it is willing tackle these issues, then fewer efficiencies will be needed. Given, however, the ongoing pressure on budgets being applied by inflation, whether it is a Conservative Government seeking to lower taxes, a Labour Government seeking to invest more in front line services or a Government of any party seeking to lowering the annual interest payments on our debt, reducing less productive areas of public spending must be a priority.

4.1. Transport

In most cases, investment in transport infrastructure should be protected, as an investment in the UK’s long-term growth. However, some major projects have been plagued by cost overruns and delays, with continued Government support being provided due to sunk-cost fallacies rather than based on a genuinely updated assessment of the cost-benefit or economic business case.

Just because a cost overrun has occurred does not mean that a project should automatically be cancelled. Crossrail overran its budget by approximately £3.8bn57https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/crossrail_-_project_at_a_glance.pdf , yet nevertheless constitutes a significant and important upgrade to London’s transport infrastructure. For this reason, decisions on whether or not to proceed or rescope should always be based on an up-to-date assessment of cost-benefit, taking into account the opportunity cost and wider economic climate.

High Speed 2 is one of the most prominent programmes that have been subject to cost overruns. In its conception HS2 was intended to increase capacity in the UK’s public transport, boosting regional growth and creating jobs. The project was intended to have three stages: phase 1 will connect London to Birmingham, and tunnelling work commenced for this part of the line in 2020. From Birmingham, the original intention was for a Y shape network, with one line going on to Crewe (phase 2a), and then furthers line going from Crewe to Manchester and from Birmingham to Leeds (phase 2b). However, the planned line to Leeds was dropped in 2021, with HS2 now planned to extend only as far as East Midlands Parkway, in addition to an extension after Crewe to Manchester.

One of HS2’s principal justifications – freeing space on the conventional lines for more commuter services – has been undermined by the likely permanent reduction in commuter rail demand post-covid. The estimated budget for the project has now shot up from an original figure of £55.7 billion in 2015 to over £100 billion, and it is reported that a new Government assessment finds that Phase 1 (London-West Midlands) will come in “many billions” above the £40bn target price. While too much has been invested in Phase 1 to cancel, the later phases are less committed, and may or may not continue to offer a positive cost-benefit. The proposed third runway at Heathrow is another project that has been dogged by delays since its inception, as well as frequently challenged by environmental groups. The most recent development in the legal situation was in December 2020, when the Supreme Court overturned a previous decision of the Court of Appeal, reinstating the Government’s Airport National Policy Statement and enabling new planning proposals to be considered58https://www.heathrow.com/company/about-heathrow/expansion . While the project itself will be privately funded, the lengthy delays create uncertainties for investors, and there may be consequential costs to the public purse for associated ground transport infrastructure.

The recent sharp increase in government borrowing costs will have a significant impact on the cost/benefit analysis of many of these projects by impacting the long-term return on investment. Changing patterns of travel post-pandemic, due to the increased prevalence of working from home, will also impact future projections of revenue. Particularly in a tightened fiscal environment, it is likely that some projects that had previously provided a positive cost/benefit outlook will no longer do so, or at least would need to be significantly be rescoped.

We therefore recommend that the Government undertake an immediate, rapid, assessment of all major transport projects, to assess whether each should be continued, rescoped or cancelled. The review should take no more than six months and should involve a range of respected, expert figures from a range of disciplines, taking into account the new fiscal and economic context, the shift in travel patterns and a proper assessment of political, legal and environmental risks that could contribute to further cost overruns.

4.2. Health and Social Care

The October 2021 Comprehensive Spending Review (SR) provided a cash uplift of £43.9bn in Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) core resource spending from £133.5bn in 2019/20, to reach £173.4bn by 2024/25.59HM Treasury. Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021. 27 October 2021 [Link] This was accompanied by a significant uplift in the DHSC capital allocation.

Spending at DHSC now substantially dwarfs any other department and has grown four-fold in real terms since the early 1980s. At the same time changing demographics in the UK, including an expanding and ageing population, is placing pressure on services. A citizen in their mid to late eighties consumes on average 10x the amount of hospital-based care as a citizen in their twenties. 60Nuffield Trust. The past, present and future of government spending on the NHS. 17 October 2022 [Link]

Given the financial picture across government, we have set out opportunities for reprioritisation and possible savings on headline DHSC budgets. NHS spending accounts for approximately 90% of the total RDEL and is the focus for this paper. We also consider the opportunities for savings within health and care ALBs and regulators, and the scope to increase revenue and reduce demand.

The NHS England budget over the SR period assumed:

- Providers would achieve an efficiency saving target of 5%. This equates to a total efficiency saving of around £5.6bn.

- The average pay award across the NHS would be approximately 3%.

- Inflation would be at 2%.

- A much-reduced COVID-related burden on the NHS, with estimated cost reductions of 57%.

The changing economic outlook since 2021 will have profound implications. The GDP deflator, which underpins Treasury analyses and is used to measure general inflation in the domestic economy, is expected to average 3.7% over the next three years.

Historically, health and care inflation pressures run above the GDP deflator. The biggest areas of impact for the NHS are pay settlements, alongside the rising costs of procuring goods and services. NHS England has estimated that this could result in a further £6-7bn per year in unanticipated costs.61NHS England Board meeting. 2023/24 financial position and the future financial outlook. 6 October 2022 [Link]

Alongside inflation, Covid-19 continues to play a higher than anticipated burden on the NHS and social care system. Daily patient bed occupancy due to Covid is higher in 2022 (9,743) than in 2021 (7,691) and 2020 (7,313), although the outlook has improved in recent weeks. Staff absences are also higher than in 2021. In response to upcoming winter pressures the Government chose to make £500m available to fund an Adult Social Care Discharge Fund for this winter.62Department of Health and Social Care. Our Plan for Patients. 22 September 2022 [Link] With performance against all NHS performance metrics in decline, attempts to review and reallocate resource must be undertaken with care. Seeking to bridge the anticipated gap in funding with further efficiency savings is unlikely to be viewed as credible. Indeed, over the next three years many areas of the NHS, from primary care to mental health, and social care system are likely to require funding to maintain basic standards of care that should be expected of developed healthcare systems. The NHS also significantly underinvests in capital as a proportion of its day-to-day revenue revenue and carried out £4bn in ‘capital to revenue’ transfers in the 2010s. Policy Exchange is therefore proposing that:

- All DHSC capital budgets are protected, with further emphasis on releasing surplus NHS land to fund additional capital spending.63The 2017 Naylor Review of NHS Property and Estates estimated that copmmercially executed disposals ofr NHS surplus land could generate £2bn-£5.7bn. We have modelled for this in our revenue assumptions at the end of the document.

- The current settlement for Health & Social Care agreed at the SR is retained, with reprioritisation from efficiencies within that settlement to the areas of highest priority.

Given inflation and higher covid-costs there nonetheless needs to be a discussion around the current revenue budget and where reprioritisation might be achieved. This is likely to require an assessment of options to reduce or reshape the focus of public services.64Paul Johnson and Ben Zaranko. Tory leadership candidates need to face reality on tax pledges. Prospect Magazine. 15 July 2022 [Link] There are no good options, only least worst options. We have outlined three below.

| Box 1: Cost of a prescription: £9.35 per item |

| Prescription prepayment certificate: £30.25 (three month) £108.10 (annual)

Prescription charging exemptions in England apply if you:

You also quality if you receive:

|

4.2.1. Reform prescription charges.

Patients in the NHS in England are charged £9.35 per item of prescription medication. Prescription charging acts as a subsidy, with those paying still protected from the full costs of medicine. Co-payment charges have a long and established history in the NHS. The introduction of prescription charges in the 1950s commanded cross-party support: the Labour Party legislated for the change in 1949, before being introduced in 1952 under a Conservative Government.

The scheme has become progressively more generous. Two thirds of the population of England qualify for free prescriptions by hitting one of the exemption criteria (see Box 1). As a consequence, 90% of all prescriptions are dispensed in the community free of charge. Once accounting for administration costs, the income received from charging for the remaining 10% is £600m per year. 65House of Commons Library. NHS charges. 6 January 2022 [Link] By comparison, the total cost for all prescriptions in England last year was £9.69bn.

The current arrangements make little sense and require reform.66Dame Kate Barker CBE. A new settlement for health and social care: Final report. 2014 [Link] This scheme was originally introduced to track the State Pension Age (SPA), which has risen to 66 and will become 67 for all those born after 1960.67Department for Work and Pensions. Second State Pension Age Review launches. 14 December 2021 [Link] The Government launched a consultation on aligning the upper age for exemptions with the SPA last Summer. It has yet to publish a formal outcome.68DHSC. Aligning the upper age for NHS prescription charge exemptions with the State Pension age. 2 September 2021 [Link] Achieving consistency between exemption and the SPA might raise a further £250m per year. A more fundamental overhaul of prescription charges would follow the recommendations in the 2014 Barker Commission, which was led by the King’s Fund (for example removing exemptions and replacing them with a cap to protect those on lower incomes and with long-term conditions).7 A simplification of the charging regime would enable the cost per item to be reduced or frozen at the current level, whilst at the same time raising in the region of £2-3bn per year for the Exchequer.

4.2.2. Direct enforcement of clinician-led review of low value NHS activity

Further decisions may need to be taken to manage financial pressure within the system. One option would be to address the commissioning of low value care – a priority for all healthcare systems.

Decisions on activities that should no longer be commissioned should be led by clinicians and focused on divesting taxpayers’ money from the lowest value care. One option would be to undertake direct enforcement of the existing and future waves of the Evidenced Based Interventions programme (EBI).69Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Evidence-based Interventions [Link] The EBI programme was established in 2019 to improve the quality of care, by reducing unnecessary interventions and freeing up resources for use elsewhere in the system. The work is coordinated by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Two earlier waves of the EBI identified 17 low value procedures and 31 low value procedures, respectively. Several procedures and diagnostics were then discouraged from being commissioned in the NHS, including surgery for snoring and exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) for coronary heart diseases – a diagnostic which was undertaken 45,000 times in 2018.

An evaluation of the first wave of the EBI found that clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in England struggled to achieve divestment from low value care. Indeed, despite a third of CCGs volunteering to be part of the demonstrator community which trialled the first wave of EBI recommendations before implementation, there were no significant differences found between the volumes of low value procedures between demonstrator and non-demonstrator CCGs.70Anderson M, Molloy A, Maynou L, et alEvaluation of the NHS England evidence-based interventions programme: a difference-in-difference analysis BMJ Quality & Safety Published Online First: 07 April 2022. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014478 In some demonstrators the quantity of low value care which was prescribed increased. This is concerning for clinicians who are the stewards of scare resources. NHS England had conservatively estimated that reduced activity across the 17 procedures would equate to a total saving of £200m per year.71NHS England, NHS Clinical Commissioners, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, NHS Improvement and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence-Based Interventions: Consultation Document. 2018 [Link]

The third wave of investigations commenced in 2022, with a final list expected in the coming weeks.

One option would be to enforce the implementation of these three waves, whilst also undertaking a fourth review which makes explicit the need to achieve financial savings, alongside assessment of whether existing interventions do not work or have been superseded by a safer alternative. This review could be expanded to include two additional areas:

Specialised services, where the costs have risen considerably in the past decade and are now more than £20bn a year. Examples include dialysis for chronic kidney disease, and specialist adult cardiology. Reforms in the way that certain specialised services such as the examples above are commissioned may create opportunities to move investment upstream to derive better value and reduce demand for specialised services in the future.72NHS England. Roadmap for integration specialised services within Integrated Care Systems. 31 May 2022 [Link]

Primary care medicines. The last guidance on ‘Items which should not be routinely prescribed in primary care’ was published in 2019 and identified medicines which had low clinical effectiveness or were low priorities for NHS funding. This wave identified 25 items at a total cost of £140m per year.

We estimate that this cumulative process across the three waves of the EBI and action on specialised services and the prescribing of low value medicines could yield savings of £1-2bn per year.

4.2.3. Shift spending towards interventions that generate good health and wealth