Traffic light, pizza connection, tiger-duck, Jamaica coalition. Anyone unexcited about next Sunday’s German federal election should find intrigue in the memorable colour-combination terms for the country’s potential governing alliances. Those combinations represent more than just pretty patterns, however. The degree of support the smaller parties gain in this election will influence how Germany addresses its most pressing issues — issues that have often seemed outside the mainstream focus, during the election campaign.

Yes, the SPD’s Chancellor contender, Martin Schulz, has criticised the CDU/CSU’s Angela Merkel for her notable reticence to discuss immigration, which is — in the fallout of her ‘open-door’ period — undeniably the most controversial topic in German politics. Yet Schulz himself has been criticised by his own party for supposedly playing into the hands of the anti-immigration right-wing populist party, the AfD, by ‘stoking’ the issue.

Moreover, Brexit famously didn’t feature in the Merkel-Schulz TV debate, even though recent polling by the not-exactly-Eurosceptic Tony Blair Institute shows that only just over 10 per cent of Germans are happy with the EU as it is. The failure of Germany’s foremost parties to revel in these issues is unsurprising: the CDU/CSU and SPD currently govern the country together in a ‘grand coalition’, and surely do not want to risk the public support their alliance enjoys.

Germany and the future of Europe

Brexit-denial aside, the election result will be crucial to the future of the EU. In his 2017 volume Europe and the German Way: Berlin Rules, former British Ambassador to Berlin, Paul Lever, explains why it is that ‘now is leaving , it is Germany that is in charge. Germany not only dominates economic policy making in the EU, it also increasingly takes the lead on international issues’. As the lynchpin of the European project, Germany’s position matters more than ever during Brexit-tide, as pressure grows throughout Europe in favour of reform or, at least, the recognition of changing circumstances.

So, what might the election results mean for the ongoing Brexit negotiations? And what might they mean for the direction of travel the EU decides to take regarding trade surpluses and bailouts? For the dissemination of Germany’s fiscal style? And for the kind of greater integration Jean-Claude Juncker called for in his State of the Union Adress last week? Should we expect yet more of the electoral surprises that recent events have taught us to anticipate? Should we trust the polling that suggests Angela Merkel is almost certain to continue on to a fourth term as Chancellor?

What is clear is that the most likely outcome is a coalition government of some colour combination. Under Germany’s complex hybrid proportional-representation-first-past-the-post system, such outcomes are practically guaranteed. (Voters get two votes: one FPTP vote for a local constituency representative; one state-counted PR vote for an overall party. The second vote is used to balance the results of the first to ensure an almost proportional result in the Bundestag.)

Merkel and Schulz

It also remains likely that Merkel will indeed win again. Her party has been polling strongly; Schulz’s honeymoon premium dwindled with the SPD’s loss of Schleswig-Holstein in the state elections in May. Moreover, as Michael Taylor writes for Policy Exchange this week, ‘one reason Mrs Merkel looks almost certain to win on Sunday is the strength of the German economy’. Employment is at its highest since the fall of the wall, and GDP is booming. Of course, as Taylor points out, much of Germany’s recent economic success hasn’t had much to do with Merkel. Indeed, labour reforms set in place by the previous Chancellor, the SPD’s Gerhard Schröder, are at the heart of the recovery — not that his successor Schulz seems to be benefitting.

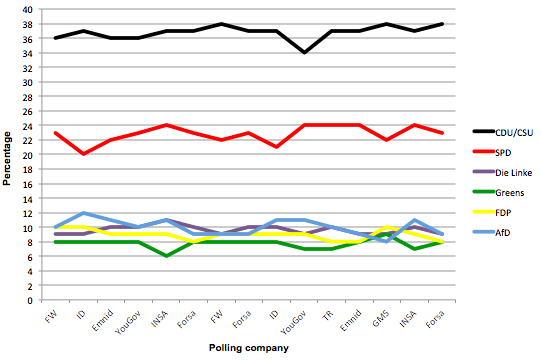

Figure: September’s main polls

The effect of Schulz’s EU credentials — you can’t get more pro-EU than having been President of the European Parliament — on his potential electorate’s opinion is something of which he must be highly aware. That awareness has been shown not least in his attempts to come across as a ‘down-to-earth’ chips-and-sausage-eating German, rather than a stereotypical cosmopolitan EU elite. Similarly, while Merkel’s response to greater European unrest has regained her some popular support after the open-door downturn, it has left her ever more tied to the project, personally. As Die Welt correspondent, Stefanie Bolzen, told me:

In a time when simultaneously the EU was in permanent crisis mode because of the Eurozone problems, and Germany was challenged by the refugee crisis, Angela Merkel has managed to position herself as the EU’s leading figure with a deep commitment to the European project and its values. Instead of putting the EU into question, she worked hard to safeguard the unity of member states. At the same time, Merkel successfully convinced a majority of the German public that in the eye of globalisation, demographic challenges, wars on the border of Europe, and political insecurity caused by Trump, Putin, and Erdogan, the EU is the best anchor for stability.

The AfD and Euroscepticism

Aside from continuity-Merkel, however, another upcoming likelihood is that, for the first time, the AfD will get in to the Bundestag, by reaching the necessary 5 per cent voting threshold. And, that — regardless of recent drops in polling and popularity (they received only 6 per cent in the Schleswig-Holstein state election) — they may even take third place. What effect could that have on German politics? And on the EU, as a whole?

The unhappy results of unaddressed Euroscepticism can be seen throughout Europe. This is exemplified by the 2017 French presidential election, in the first round of which, 40 per cent voted for explicitly Eurosceptic candidates — regardless, for many of them, of the candidates’ other more controversial positions. Yes, many of those voters did not then go on to vote on Eurosceptic grounds in the final round, yet Marine Le Pen still received over 30 per cent of the vote. In contrast, consider the fall of UKIP in the recent UK general election. If even lynchpin Germany is only 10 per cent happy with the EU’s current instantiation, then suppressing Euroscepticism does not seem a sensible option for Europe.

The new German coalition will need to address that problem and more, and its make-up will be essential to deciding its approach. The least likely outcome is a coalition without Merkel in charge, although William Cook points out on the Spectator blog this week that the high number of undecided voters means a ‘red-red’ solution must remain a possibility. However, the polling shows a keenness for continuity. If the current grand coalition of the CDU/CSU and SPD were not to continue in place, then the CDU/CSU’s partner options would be the Greens and the FDP (as Merkel has, unsurprisingly, ruled out the AfD and the far-left Die Linke).

The FDP and Britain

The FDP has been at the centre of post-war German politics, and formed the junior partner of Merkel’s second coalition, before losing its place in the Bundestag in the 2013 election, after receiving only 4.8 per cent of the vote. Seen as a party of centre-to-centre-right classic liberals, Christian Lindner was elected its leader following the last election. In a recent interview with the Economist, Lindner argued that German prosperity is a ‘prosperity hallucination’; the FDP is campaigning for tax cuts and a points-based immigration system.

While the party remains pro-EU, it has a strong Eurosceptic wing, and, as Leopold Traugott argues for Open Europe, the FDP re-entering Germany’s governing coalition would seem to be in Britain’s interests — not only because the party is keen to avoid a punishing approach, but also because it would provide ‘a stronger voice in the Brexit negotiations for German business, the sector that has most to lose from a punitive Brexit deal’.

Might such an approach provide a useful counter-balance to the strongly pro-European stance favoured by Merkel? Bolzen summarises that:

During her election campaign, Brexit has served Merkel as a blueprint of what, in her view, is the wrong answer to those challenges . Isolation instead of cooperation. She has been adamant that the EU Commission will lead the first phase of the Brexit negotiations. And that even when talks move on to future relations, the UK’s status outside the EU must be less privileged than as a member. Bearing in mind that her pro-European credentials are part of the platform on which she probably will be re-elected, it is doubtable that Merkel will throw her weight in for a Brexit deal that favours economic interests ahead of the EU27’s integrity.

While it is most likely that Merkel will continue as Chancellor, recent times have shown resting on likelihoods to be a risky game. Something of which we can be sure, however, is that Germany will remain at the heart of a volatile Europe. What happens next will affect us all: we must keep watching carefully.