The UK economy is in good shape – that was the message from a slew of data published last week, including progress on the elusive productivity challenge. This cheery message comes with a warning, however. The data indicate there is little spare capacity in the economy and the Bank of England should be mindful not to allow things to overheat.

The data were a combination of strong public finance numbers, higher employment in a labour market that is close to full employment and a rise in productivity. The revised GDP figures for the fourth quarter of 2017 took reported growth down from 0.5 to 0.4 percent, yielding GDP growth of 1.7% between 2016 and 2017

The downward revision to GDP data in the fourth quarter was a result of further information and reflecting a small downward revision to the estimated output of the production industries. There was a decrease in mining and quarrying output in the quarter due partly to the shutdown of the Forties pipeline system (FPS) for a large part of December 2017. Within production, manufacturing was the only sub-sector to increase, growing by 1.3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2017 compared with the third quarter of 2017.

Rising Employment

The employment report based on the Labour Force Survey showed that unemployment rose by 0.1 per cent to 4.4 per cent. It remains 0.4 per cent below its level in the three months to December 2016. Employment increased in the three months to December 2017, by 81,000 compared to the previous quarter and 321,000 compared to the quarter a year before. There are now 32.15 million people in work. The rise in employment was driven by an increase in full time employment of 136,000 to 20.20 million in the three months to December 2017.

Finally Rising Productivity

Productivity growth in the recovery since the trough of the Great Recession has been weaker than in previous economic cycles. This has been a shared experience among advanced economies, although the UK exhibits other longer standing productivity challenges that are particular to its own experience. The latest productivity figures for the fourth quarter of 2017 however are encouraging. Productivity increased by 0.8 per cent, following a 0.9 per cent rise the previous quarter. There now appears to be something of a cyclical pick up in productivity, although whether it is strong enough to make a dent in the UK’s relatively poor international productivity performance is another matter. The McKinsey Institute this week in a paper on international productivity held out hope for advanced economies. The burden of the analysis is that with time technology and digitisation in sectors such as retail will yield higher productivity growth.

Strengthening Public Finances

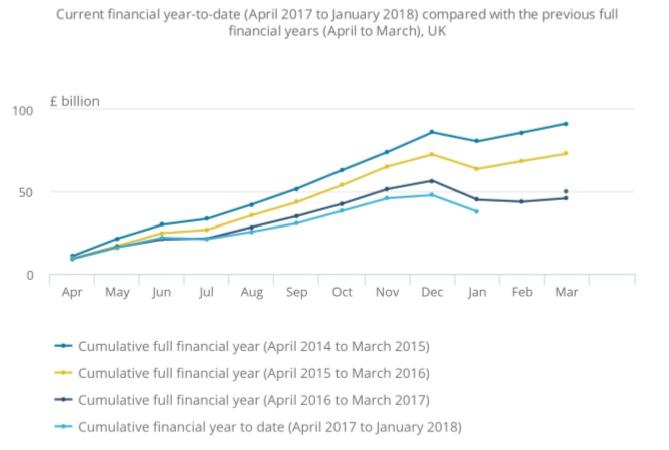

In many respects the best news for the UK economy came from the public finances. Public sector net borrowing fell by £7.2 billion to £37.7 billion in the year to date compared with the same period in the previous financial year. This is the lowest year-to-date net borrowing in the financial year to date ending in January 2008. January is normally a month when the government spends less money than it collects in taxes. The surplus in January of £10 billion was the second highest monthly surplus since April 1993. This is good news for the Chancellor in terms of narrow budget arithmetic, but economically it is interesting as well. Much economic data is based on surveys – where information is incomplete and estimated. The public borrowing figures in contrast are hard real data and they imply a steadily maintained pace of economic expansion.

It is just as well that the UK is making progress in strengthening its public finances. The OECD’s senior fiscal policy analyst last week warned OECD economies that they have high debt burdens with an increasing refinancing burden arising from maturing debt and continued budget deficits. Oddly over the last couple of years the OECD has been sanguine about public debt suggesting that economies had the fiscal space to stimulate economic activity through changes in spending and taxation. It has now changed tack warning about the malign implications of a 1 per cent rise in ten year bond yields worsening budget balances by 0.1 to 0.3 per cent.

The US Council of Economic Advisers also published its annual Economic Report of the President last week. In the report’s Global Macroeconomic Situation section it concludes that economic activity in advanced economies and regions such as Germany, France, Japan and UK is close to the point where growth exceeds the potential or trend rate. There are few negative output gaps and their realistic trend rates of growth are below that of the pre-crisis level. This is entirely consistent with our view of UK economy at the moment.

Public sector net borrowing (excluding public sector banks). Current financial year-to-date (April 2017 to January 2018) compared with the previous full financial years (April to March), UK.

Public sector net borrowing (excluding public sector banks). Current financial year-to-date (April 2017 to January 2018) compared with the previous full financial years (April to March), UK.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Flexible Product Markets

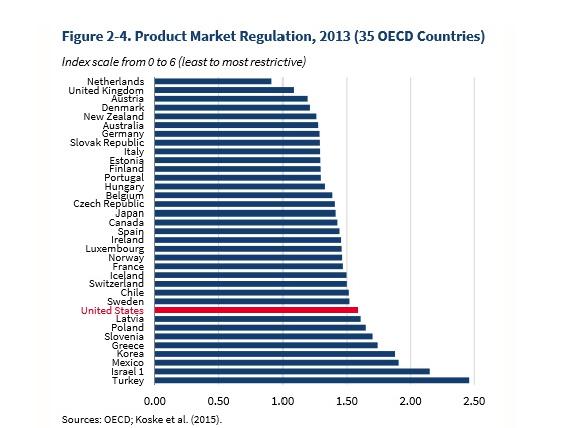

The Economic Report in its chapter discussing regulation has an interesting diagram showing the relative burden of product market regulation in OECD countries. Of the thirty-five countries scored the UK has the lightest level of regulation second only to the Netherlands. This illustrates the flexibility and relative structural strength of the UK economy. The UK enjoys flexible product and labour markets, an independent monetary policy and floating exchange rate that can adjust to changing circumstances and respond to adverse shocks.

Time for the central bank to take the punch bowl away

Identifying the relative flexibilities of the UK economy however cannot disguise the fact that the UK is in the stage of the economic cycle where monetary policy should aim to prevent things overheating. It has to ensure that the pace of expansion does not exceed the economy’s productive capacity. Over the last twenty months the central bank has operated what is in effect a pro-cyclical monetary stimulus and been reluctant to adjust domestic monetary conditions to the capacity constraints. Change should be in the offing.