Wave energy, tidal lagoons and small modular nuclear reactors. Three technologies that stand on the precipice of mass deployment in the UK, but that are seeking Government action to help kick-start their development and bridge the crucial gap between the demonstration phase and commercial viability. The difficulty for Government Ministers is in assessing the scope for each of these technologies to reduce in cost over time and balancing this against the level of support that would be required to achieve this. Most recently, reports in the media have suggested that the Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy are wavering over their support for the Swansea Bay tidal lagoon, with concerns centring on the “eye-watering” expense of the project.

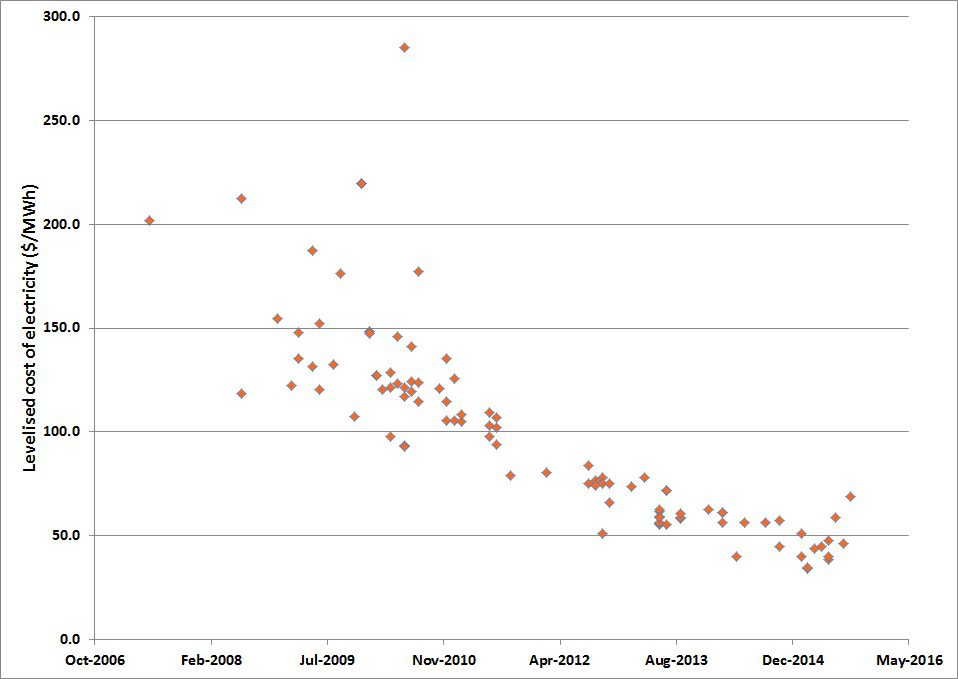

Typically the cost of manufacturing anything the first time is always relatively high, but will fall over time as companies implement better production methods and develop their supply chains. In academia the general term used to describe how the costs of a new technology will fall with increased deployment is technological learning. The metric used to describe the rate of reduction is referred to as the learning rate. In the energy field, it measures the percentage cost decline that is achieved for each doubling of generating capacity added to the system. A major success story in technological learning has been in the solar sector, which has seen substantial cost reductions in the last decade. The plot below shows the levelized cost of electricity of solar power in the USA for a sample of projects since 2006 (source).

Levelized cost of electricity of solar power in the USA

Levelized cost of electricity of solar power in the USA

It is difficult to predict the learning rate of future technologies, but we can point to the characteristics of a technology that make it more likely to reduce in costs than others. They will:

- Be a standard, replicable design;

- Be factory produced;

- Not have a large percentage of their costs subject to variables that cannot be controlled.

Solar panels ticked all three boxes, which is one reason why they have achieved high learning rates estimated to be between a pretty decent 10% and a quite staggering 53%. Conversely, those energy technologies that are more difficult to bring down in cost through learning will be large bespoke infrastructure projects, like hydro-electric power plants or large-scale nuclear reactors (a reason for current interest in small modular reactors, which are factory produced and offer much more potential for cost reductions through learning-by-doing).

This is why the case for giving tidal lagoons a high level of financial support is less strong than it would have been for solar and wind. Each lagoon will be a bespoke civil engineering project, so there is less potential for high rates of learning. This does not mean that developers will not be able to bring down costs, but the rate of technological learning is likely to be lower than we have seen with solar panels and wind turbines. Analysis by Poyry suggests future tidal lagoons could produce electricity at lower cost, but due to the fact that the next projects will be larger with a greater tidal range, not due to learning. This does not take into account, however, the well-documented tendency for large, complicated infrastructure projects to go over budget and behind schedule.

Predicting the rate at which costs will fall in the future is very challenging. Even properly measuring the rate at which costs have fallen in the past is often not that easy. Cost data is not always available (it may be commercially sensitive) and the measured learning rate will depend on various input assumptions, like the time period covered for the calculations.

Another reason why it can be difficult to measure is because it can be driven by different processes, some of which may interact or overlap, so it is not always easy to attribute cost reductions to one process alone. An added complicating factor in the estimation of learning rates is the fact that some elements of cost are not controllable. Rises in labour costs, for example, may cancel out any gains achieved through more efficient production processes. The other crucial component of cost is that of raw materials – lithium-ion batteries have been getting less expensive, but a worldwide bottleneck of lithium mining could push prices back up again, albeit temporarily.

When looking at the portion of costs that are subject to technological learning, the ways in which these can be brought down include:

- Learning-by-doing: This is where a company will develop more efficient methods of manufacturing an item. For example, a wind turbine company may introduce robotics into their manufacturing processes, thus allowing output to increase.

- Learning-by-researching: Quite often research and development can deliver step changes in performance of a technology that cannot be achieved through the more evolutionary process of learning-by-doing. In battery technology, a switch from lithium-ion to solid state technology could deliver more efficient, longer lasting batteries that would reduce the lifetime cost of electric vehicles.

- Learning by using: The cost of building large nuclear power plants has not come down over time in the same way as solar panels or wind turbines. However, operators have improved the economic viability of existing plants by increasing their performance. Nuclear reactors today have much less down time for maintenance and refuelling than in the past. The output of nuclear power plants in America has risen by almost 50% since 1990, greatly increasing the revenue gained per unit of capacity.

One can never be sure if and by how much costs of a new energy technology will decline. Few people thought wind power could achieve such gains in such a short space of time. Unfortunately, often the only way to find out is to go through the expensive process of an initial build programme. This uncomfortable truth is probably not something Government Ministers and private sector R&D managers with constrained budgets want to hear.