This Budget matters.

In the last Parliament, many of the most important decisions for the fiscal strategy of the next five years were baked in from the very first Emergency Budget of June 2010. The OBR’s forecasts for growth and unemployment may have changed, but the Chancellor stuck to his consolidation, tax rise and spending cut numbers. Together, this year’s Summer Budget and Spending Review are likely to play the same role for the upcoming Parliament.

A lot of the big picture we already know. We know the rough balance of savings the Government wants to find between tax, welfare and departmental spending. We know the rough envelope for total public spending that the Government intends – currently predicted to be 1% higher in real terms in 2020 than today – and we know that within that it intends to keep ring-fencing spending on health, schools, international aid and infrastructure. The Chancellor doesn’t want to raise the overall level of taxes, but he does want the UK to be running a surplus.

But despite all this detail, there still remain a few key questions, the answers to which will have a big impact on future spending levels:

1) How many savings does the Government need to find?

The Conservative Manifesto pledged to find £30bn of new savings by 2017-18: £13bn from departmental savings, £12bn from welfare, and £5bn from reduced tax avoidance. On the 4th June, the Chancellor announced that the Government had already found an extra £3bn of savings for 2015-16.

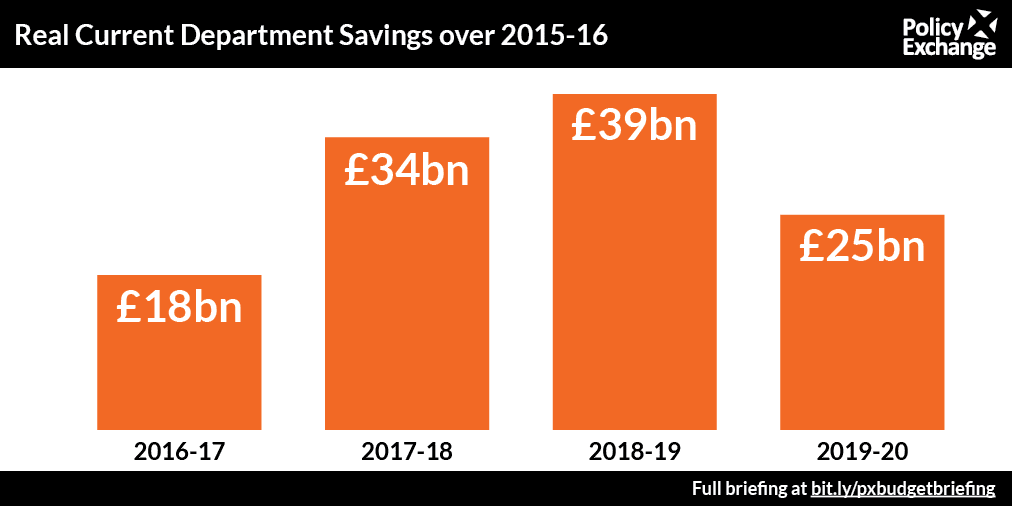

But this number isn’t a complete picture of what’s to come. To start with, under the OBR’s current forecasts, even after the £30 billion has been found departmental spending is set to continue falling for an extra year in 2018-19.

More to the point, over the course of the election campaign, the Conservatives committed or confirmed another £15-20bn or so in policy commitments: another £8bn for the NHS, higher tax thresholds for income and inheritance taxes, more for the aid budget, for schools, for childcare, for rail passengers, and for infrastructure spending overall.

Does this mean we need to increase the overall level of savings needed by another 50% or so?

Not necessarily.

The Government has left itself at least three different ways of giving themselves more room for manoeuvre.

2) How big a surplus does the Government want?

To start with, while the Government has been clear that it intends to run an absolute surplus, it has been far less clear how large it intends for this surplus to be. While other countries in the past have aimed for, say, a surplus that averages 1% of GDP, the Government’s intention could be technically met as long as it brings in one pound more in tax revenue than it gives out.

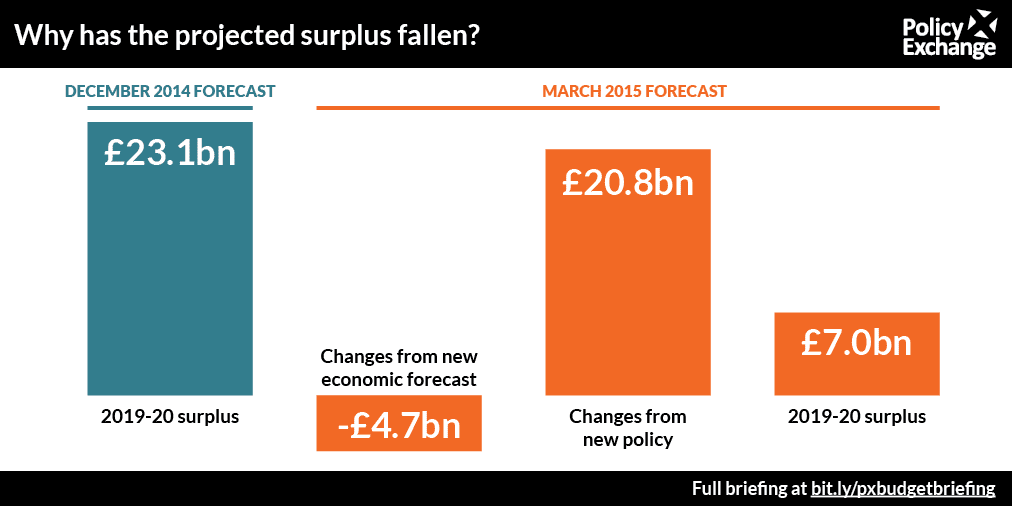

The March 2015 Budget already saw the surplus for 2019-20 fall from the Autumn Statement’s prediction of a £21.1bn to a much smaller £7bn. This came about entirely because of policy decisions, rather than any worsening of the long term forecasts: the government choosing to change its assumption that future government spending will grow with inflation, to one in which it grew with the economy as a whole.

Given the unreliability of economic forecasts, having some margin for error in the target is a good idea. Nevertheless, if the worst came to the worst, dipping into that extra £7bn could basically pay for the extra spending pledged for the NHS, or alternatively the higher tax thresholds, while maintaining the Government’s commitment to balancing the budget.

3) Will the Government increase any taxes?

The Government’s proposed new tax lock law looks to be surprisingly comprehensive, with the details revealed at the Queen’s Speechsuggesting that it would exclude any rises in the main rates for income tax, VAT or National Insurance, but also any stealth increases to the employee NIC upper earnings limit or the scope of VAT. No more pasty taxes.

Nevertheless, there still remain other ways of raising tax, and doing so would help the Government pay for its proposed tax cuts without further increasing the level of public spending cuts. It is not just all about income tax either, or the weekend’s confirmed raise in the inheritance tax threshold to £1 million. Current forecasts assume that fuel duty will increase with RPI, which given the Chancellor’s past record of successfully freezing it seems unlikely. If the Government is serious about limiting the “merry-go-round” between tax and welfare, it also might be tempted to look again at the employer and employee National Insurance thresholds, which currently take effect at much lower levels than the Personal Allowance.

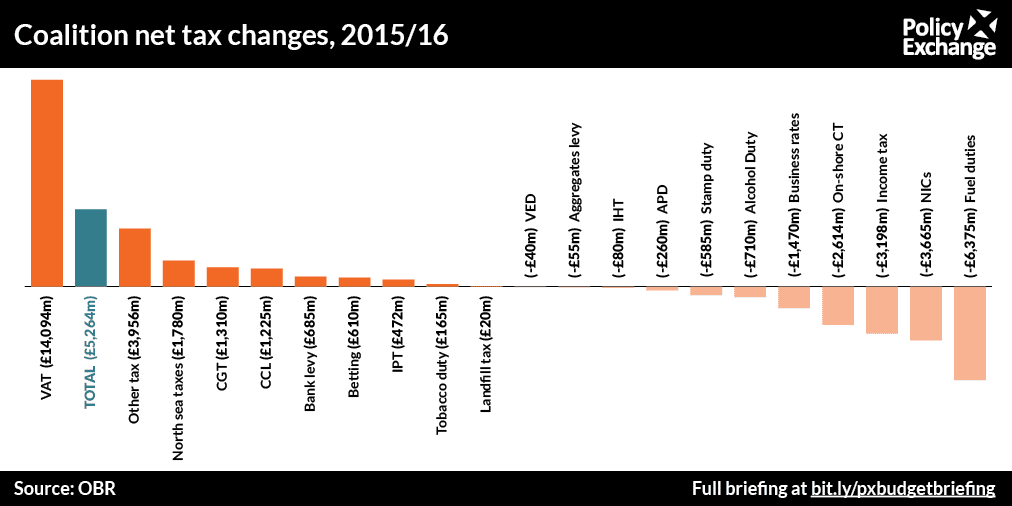

Over the last Parliament, the Coalition increased the Personal Allowance from £6,475 to £10,600 and spent over £6bn postponing rises in fuel duty – while at the same time managing to increase net tax revenue by £5.2bn. It did so, however, largely through its one off increase to VAT, which is obviously not going to be repeated this time.

What taxes might the Government increase this time instead to pay for its giveaways? There are many possibilities, from a higher bank levy to further clampdowns on non-doms.

The Conservatives have already committed to reducing tax relief on pension contributions for those earning above £150,000 to pay for the changes in inheritance tax, but going further on this could potentially bring in significant revenue – the IFS estimated up to £10 billion if you restricted tax relief to the basic rate for everyone.

Secondly, while the Conservatives are obviously unlikely to bring in their own explicit mansion tax, they could bring in similar levels of revenue much more simply either through increasing the rates for the higher council tax bands G and H, or the introduction of new still higher bands on top of these.

4) Will the Government smooth out the rollercoaster?

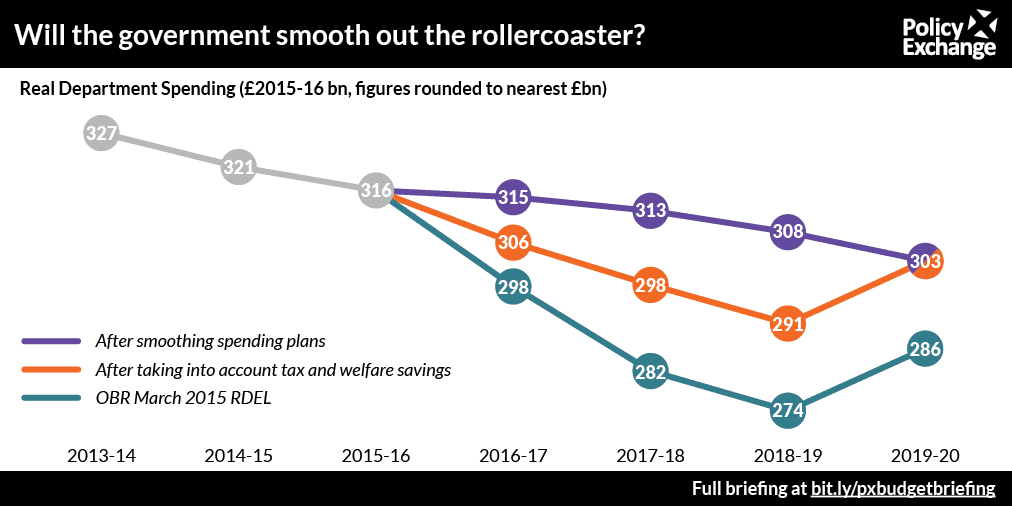

As we saw above, the current OBR forecasts see departmental budgets suffering particular sharp falls in the first two years of this Parliament, followed by a year of slightly softer cuts after that, which is immediately more than reversed in the final year of the forecast of 2019-20.

Taken literally, the OBR’s forecasts can be misleading. They are based on the principle that nothing will change policy-wise: no £12bn in welfare savings, or £5bn from lower tax avoidance. When you take these into account, the total real cut for the three years from 2015-16 to 2018-19 falls from 13% to 8%.

But even if you take that into account, the rollercoaster still exists. Smoothing it out – ultimately reaching the same place, but not seeing such a drastic U-curve in the middle – would take the overall level of real cuts down to 4%. It would give the Government an extra £15bn to play within 2017-18 or an extra £18bn in 2018-19, and significantly longer to phase in structural changes to reduce welfare or increase public sector efficiency. Some city analysts are already predicting that this is likely.

In the last Parliament, the Government achieved a significant proportion of its welfare savings through increasing benefits slower than the rate of inflation as whole – which is clearly much harder over just a two year period, especially in a time of very low inflation. On the departmental side, we currently have no agreed overall metric for what proportion of the cuts came from ‘efficiency savings’ – although we do know that the Cabinet Office managed to find about an additional £5bn every year from the elements of the public sector under central control and that it could measure.

Whether the Government could do this, and stick to its fiscal promises is a different question. On the one hand, the Fiscal Mandate from the Coalition Government’s Charter for Budget Responsibility – renewed only last autumn – is explicitly designed as a rolling target, with the ultimate deadline getting pushed back every year.

On the other, the Conservative manifesto explicitly called for £30bn of consolidation by 2017-18 – and of course, smoothing out the cuts wouldn’t be without its implications for higher debt, or running the risk that by putting it off so long we hit another recession before the job of balancing the budget is even complete.

At this point, it is far from clear which of the Government’s many fiscal rules and assumptions – its path for government spending, the Charter for Budget Responsibility or the fiscal consolidation numbers – is supposed to be binding.

If the economic forecasts unexpectedly improve by the time of the Summer budget, will the Government row back from its £30bn number, or will it take advantage of the reduced headwinds to cut debt still faster?

5) What is a ‘normal’ economy?

Which brings us to the fifth critical unknown: the Government’s new fiscal rule, announced in the Chancellor’s Mansion House speech, that in “normal times”, the Government should be running a surplus. Chris Leslie, Labour’s new shadow chancellor, has already signalled that his party is likely to back the changes too.

This rule has already caused a fair amount of controversy – which is slightly strange, given how little we know about it.

Among the many unknowns that could affect whether the rule is too harsh or too lenient, too flexible or too strict:

- How big does the surplus have to be? Does the government intend to run a sizeable surplus of 0.5% or so to ensure some leeway, or will a balanced-budget-plus-a-pound do?

- What happens when the Government misses the target? Does it have to make up the difference with a still larger surplus next year – an automatic stabiliser system – or does it get a few years of grace to return to balance?

- What count as ‘normal’ times? Any time growth is above some number? The output gap at zero? The Bank of England not constrained by the zero lower bound on interest rates?

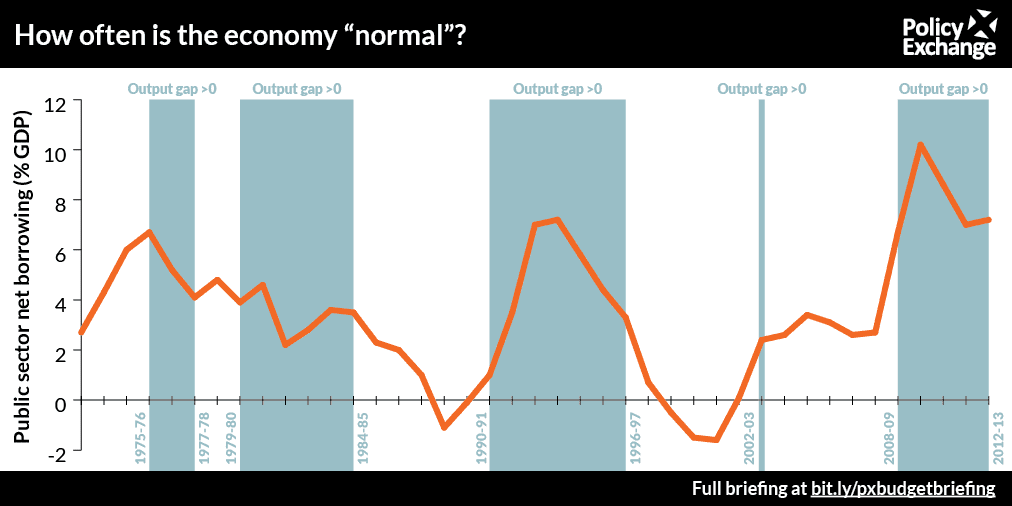

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that we define normal economic times as those in which the output gap – a measure of the spare capacity left in the economy – is less than zero. Under this measure, the economy would have been ‘normal’ in under half of the last forty years –and run surpluses in about a quarter of those.

Finally, one more bonus question: how much detail are we actually going receive at this Budget, and how much will we still be waiting for till the autumn’s Spending Review?