The economic wellbeing of political communities does not turn on the size or scale of an economy or political entity, but on good economic policy. The question of whether Scotland should be independent or remain part of the UK is not therefore principally an economic question, but a political one. Part of the political question, however, involves an economic assessment of the capacity of an independent Scotland to forge economic institutions and policies that will deliver good policy and a flexible economy that can adjust to changing circumstances.

The challenges that confront all advanced economies

Most OECD economies are presented with the awkward challenge that comes from the combination of developed and expensive welfare states bearing the costs of aging populations and increasingly competitive markets. This is a challenge from which none of the UK, the US, or the EU are immune — and an independent Scotland would not enjoy immunity either.

De-industrialisation and an increasingly concentrated UK tax base

In some respects, the Scottish challenge is more acute than that of many other economies. Scotland has received substantial transfer payments throughout the post-war years, which became formalised in the 1970s in the so-called Barnet Formula for the Scottish block grant. This has financed higher levels of per capita spending in Scotland than in the UK as a whole. Over the last fifty years, economic activity has become more geographically concentrated, reflecting the process of de-industrialisation, the shift to services, and the increased importance of financial services in London. The result is that the UK’s tax base has become more concentrated. The potent combination of higher than average public spending in Scotland, and an asymmetric tax base concentrated increasingly in London and the South means that public spending in Scotland exceeds tax receipts.

Scotland’s budget deficit

Scotland has an actual budget deficit of £15 billion: around 9 per cent of GDP. Taking account of the ups and downs of the business cycle, however, Scotland’s structural budget deficit will probably be greater. Independence would present an immediate fiscal challenge, which would probably get worse rather than better. Its resolution would involve difficult financial choices: either significantly lower spending or significantly higher taxes. Higher taxes might not result in a sustained increase in tax receipts, and might in the medium term further erode Scotland’s potential tax base, given the ease with which businesses and earners could move to England.

An enterprise economy, and a nation with nostalgia for social democracy?

The SNP ministers have presented independence as an opportunity to create a dynamic enterprise economy and to embrace a somewhat nostalgic picture of European social democracy, where Scotland would enjoy higher levels of public spending, greater levels of equality, and the protection of a more regulated society. High public spending, taxation, and regulation do not reconcile with high levels of growth and a dynamic enterprise economy, however.

Public-sector efficiency in Scotland since 1998

The First Minister’s suggestion that Scotland’s fiscal deficit can be resolved by growing receipts from a higher tax base is implausible, and it would be even less realistic in the context of a broad social democratic agenda directed at expanding public services and social protection. Increasing productivity by improvements in training and education plays a part in every optimistic progressive policy agenda, but it nearly always turns out to be a challenge beyond the capacity of governments. In Scotland, it will present a particular challenge. In each report published since 2006, the OECD PISA assessments show that Scotland’s educational performance has declined relative to other OECD countries.

Scotland’s disappointing relative performance in relation to education reflects wider issues in public-sector effectiveness. In most areas of public service, public spending in Scotland is higher than the UK average. Yet the comparative results of the spending are at best ambiguous, when they are not disappointing. Since 1998, Scottish ministers in the Labour, Liberal Democrat, and SNP parties have used their discretion to undo partially public-service reforms made in the 1980s and 1990s, and to avoid the public reform agenda since 2000. Scottish ministers have accommodated public-sector producer interests, rather than challenged them. The conduct of the Scottish executive since 1997 does not suggest that an independent Scotland would be a model of efficiency, economy, and effectiveness, in which the public sector would adjust to changing and difficult circumstances.

Brexit makes the case for an easy separation more difficult

In 2014, the independence proposition was that with both the UK and Scotland in the EU, no one would notice the difference in terms of commerce and trade. Brexit destroys that proposition. The UK will be out of the Single Market, the Common External Tariff, and the Customs Union. In or out of the EU, Scotland will face a huge challenge separating itself from the UK, where it does sixty per cent of its business. In 2014, Scotland faced vexing questions over which currency it would use — and how its taxpayers could have the capacity to underwrite its banks — in the event of a financial crisis. These questions remain relevant today.

Will Scotland’s oil remedy its financial problems?

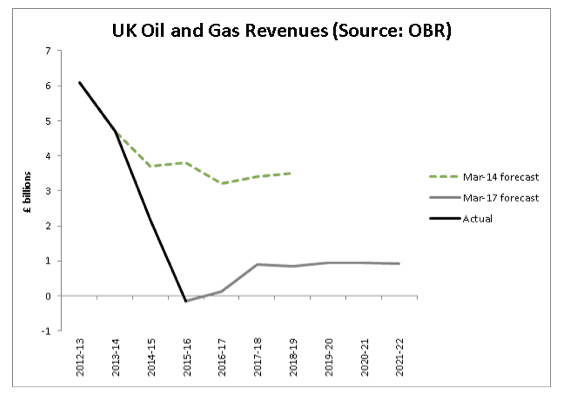

The SNP and the independence agenda took off in 1974 after the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973, which made the extraction of oil in the North Sea commercially viable. The SNP won seats at Westminster on the slogan of ‘Scotland’s oil’. At the time of the 2014 Scottish Independence referendum, the view of the OBR was that North Sea Oil and Gas taxes would yield around £3-4 billion per year for the next few years. However, as a result of the shale boom in the US, global oil and gas prices fell sharply in 2014-15. Oil prices, for example, fell from just over $100 per barrel in summer of 2014, to below $40 per barrel, returning to around $50 in recent months.

This had a significant knock-on impact on North Sea Oil and Gas activity, reducing the amount of new investment in the basin. It also means that the OBR has significantly revised down its expectation of current and future revenue from North Sea Oil and Gas taxes. These fell to zero in the 2015-16. The OBR now expects total North Sea Oil and Gas taxes to amount to £1 billion per year or less for the foreseeable future. A realistic assessment of receipts from oil does not suggest a significant fiscal windfall that would modify the fiscal challenges of an independent Scotland.

Like most advanced economies, Scotland will face awkward challenges. Its public finances at any point of independence would be exceptionally difficult, and the UK’s decision to leave the EU will mean that the Scottish Government’s ambition to remain in the Single Market will be more expensive to accomplish.