The Prime Minister’s announcement last week that ‘austerity’ would end and that the Conservative Party had got the message is good politics. Post-Brexit, the Conservative Party has a political challenge. This is to turn itself into an effective people’s party that enjoys broad support of the sort that the post-war right-of-centre parties attracted in countries such as Australia, Austria, Canada and West Germany. This has to be based around practical notions of social security, prudence, opportunity and community. It involves a welfare state that works for people, an economy that can generate jobs and rising private living standards that are protected by effective borders, police services and strong defences.

A Social Market Economy that works for people

Any budget or comprehensive spending review should read like a political vision with numbers attached. The Prime Minister and the Chancellor need to fashion a public spending agenda that does that. The starting point should be what the UK has got right. It is a large, wealthy economy with high levels of employment, a trend rate of growth higher than most of its continental neighbours, a budget deficit that is moving towards rough balance and public finances that are under control. It has a framework of taxes and benefits in cash and in kind that significantly modify household income in favour of the bottom third of the income distribution. In short, the UK is a social market economy that works.

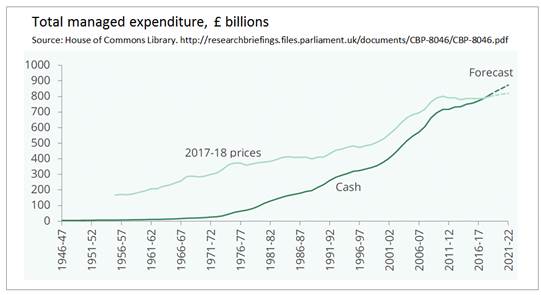

Britain is good at extracting large amounts of tax revenue from the very top of the earnings distribution – the top 1% of income taxpayers contribute more than a quarter of all income tax. This suggests that it in terms of maximising revenue yield, little more can be obtained from the top and a significant rise in public spending can only be financed by levying a higher effective tax rate on households in the middle and lower part of the income distribution. This is both an economic and a political constraint on the spending ambitions of any government. It is a particular constraint on a Conservative administration that, recognises the importance of giving individuals and families the opportunity to spend more of their own money.

Realism about what can be achieved

The Government’s approach to the spending review should be informed by realism. This should start with the appreciation that all public spending involves a real resource cost. This is greater than its cash cost, because of the deadweight costs and economic distortion that arises from the taxes necessary to finance it. There are diminishing returns to public spending and it involves opportunity costs. Public spending that yields clear economic and social returns, including spending on the welfare state, enhances the performance of the economy, but beyond a certain point the cost is greater than the return and government spending begins to crowd out private sector economic activity and the tax base that public spending depends on. Vito Tanzi, in his seminal work on international public finance, suggests that by the 1960s and 1970s most advanced economies had taken public spending to the level where returns were diminishing and it crowded out private activity. The choice governments in advanced economies face is between higher spending today and a slower growth in the tax base; or lower spending and a stronger tax base that can finance higher overall spending at a lower ratio of national income in the future.

Spending priorities

Realism about these constraints does not mean that the Government cannot fashion a prudent and attractive public spending programme that increases discretionary spending on specific programmes, reorders spending priorities and sets spending in the context of a falling stock of government debt and ratio of public spending that is contained as a share of national income to below two fifths of GDP. Such a programme would focus on targeted spending on programmes that exhibit obvious pressure and give greater priority to important functions that have been neglected.

There are two broad areas of public spending that have been neglected and under-resourced for more than a generation. These are defence spending and spending on social care. The issues surrounding social care can be traced back to the 1940s when the NHS was set up. The neglect of defence spending arises from the Options for Change White Paper in 1990, the determination to achieve an unrealistic peace dividend following the end of the Cold War and from a transformed and contemporary challenging international environment.

Further targeted spending

There are also areas of spending that need focused discretionary increases in spending. These include certain parts of local authority spending, such as children’s services and the support of adults with disability. Spending on police, prisons, probation services and courts have been squeezed for more than twelve years. Mental health and related community services also need targeted help.

Learning from past mistakes

The Government should try and learn from the mistakes of previous governments. Big discretionary increases in spending programmes do not yield results that are consistent with the additional resources applied.

A swift unrealistic increase in spending tends to inflate the cost base of the public services rather than increase its output. Many ‘resources’ in the public sector do not turn simply on money. Occupational therapists, speech therapists, mental health practitioners and probation officers require training, experience and unusual qualities and temperaments. Large increases in capital spending without the revenue budget to pay to service the hospital operating theatre or school laboratory will fail. A large part of the disappointment of the New Labour spending was the mismatch between new capital assets and the absence of trained staff that could be recruited to work in them. The best results will come from spending on mainstream services rather than trying to establish parallel services that, for example, replicate the work of health visitors or social workers working on child protection. In terms of capital investment, the greatest results tend to come from smaller local projects rather than large, high-profile infrastructure projects. The highest returns of all come from maintaining what you already have by repairing things properly.

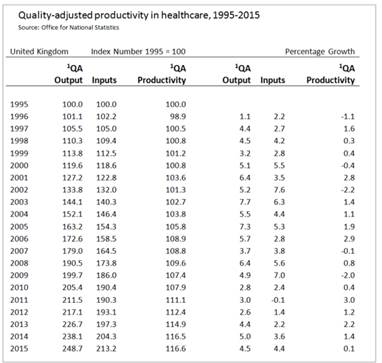

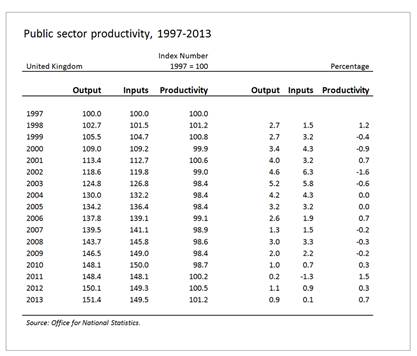

The discretionary increases in public expenditure between 1997 and 2010 provide a cogent cautionary tale. Public spending rose 114 per cent in cash terms and 59 per cent in real terms. Yet increased spending did not translate to commensurate improvements in outcomes. The ONS measurement of productivity in public spending – an innovation arising out of the New European System of national accounts – shows that productivity fell. In contrast, since 2010 public sector productivity has increased and increased noticeably in health spending. A more careful and incremental approach to public services is likely to yield better results than huge increases in cash spending.

Making public spending more efficient

There are still big efficiency issues in public spending, particularly in central government spending , which has not been subject to the same degree of fiscal constraint and adjustment as local authorities. The public would welcome a serious attempt to increase the results from what the taxpayer already spends. There needs to be more information from central government departments about their unit costs and the results of their spending. Since the mid-1980s, governments have shied away from managing their own cost base. The public sector wage premium remains in place, pay and pensions for people doing similar work to other people working in the private sector still look generous. Managing staff at work in terms of getting the most out of them remains an issue. There continue to be losses of X-efficiency. To avoid the difficult task of controlling its own cost base properly and managing its work force effectively, the public sector has relied on outsourcing. This has helped to contain costs but at the expense of efficiency and reliability in service provision. The time will come when the public service will have to look at these issues again robustly. They involve awkward matters, such as sickness at work, regional pay and the generosity of pensions. Yet they are questions that go to the heart of the public sector’s efficiency, effectiveness and economy.