The Government finally ended 19 months of uncertainty – with Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Secretary of State Greg Clark announcing the decision to reject the Swansea Tidal Lagoon because the “proposed programme of lagoons do not meet the requirements for value for money”. This was framed against the Government’s “clear commitment to bear down on costs.”

At Policy Exchange’s recent event, Ten years on from the Climate Change Act: Successes and Shortfalls, Minster of State at BEIS Claire Perry – echoing Clark – stated that low carbon projects should be assessed against the ‘three C’s’ – carbon reduction, consumers’ bills and competitive advantage. It is therefore important to consider the decision against this backdrop.

Consumer Bills

Policy Exchange was one of the earliest objectors to the scheme, writing about the Folly of Swansea Bay in January 2017. Expressing scepticism about the project, it was argued that it should not be forgotten that tidal lagoons would need to be paid for by energy users (households and businesses) through a levy on households bills. Subsequently, senior sources within Government confirmed that highlighting the impact on consumers, Policy Exchange provided a strong independent voice to the debate served as a ballast for government thinking.

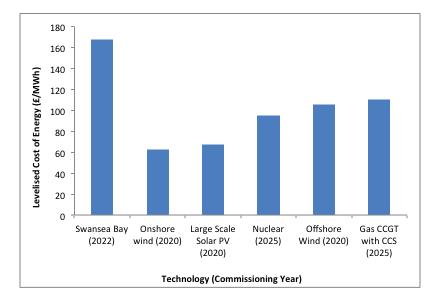

Tidal Lagoon Power had been seeking an initial contract with the government that would involve the taxpayer agreeing to buy electricity for 90 years, which would have been more than double the length of the 35 year contract on offer for Hinkley Point nuclear power station. By comparison, offshore wind projects received contracts of 15 years. In order to get a sense of the relative costs, it is useful to compare the cost per unit of electrical output (£/MWh) – often referred to as the ‘Levelised Cost of Energy’- for different technologies. A 2014 report to the developers put the cost of Swansea Bay at £168/MWh, roughly four times the current wholesale price of electricity. By comparison, the Government’s own estimates show that other low carbon technologies are considerably cheaper.

Tidal Lagoon Power had been seeking an initial contract with the government that would involve the taxpayer agreeing to buy electricity for 90 years, which would have been more than double the length of the 35 year contract on offer for Hinkley Point nuclear power station. By comparison, offshore wind projects received contracts of 15 years. In order to get a sense of the relative costs, it is useful to compare the cost per unit of electrical output (£/MWh) – often referred to as the ‘Levelised Cost of Energy’- for different technologies. A 2014 report to the developers put the cost of Swansea Bay at £168/MWh, roughly four times the current wholesale price of electricity. By comparison, the Government’s own estimates show that other low carbon technologies are considerably cheaper.

These economic realities remain the same today, despite the best efforts of the developer and its backers. In a recent evidence session to the BEIS commons committee, the Chief Executive of the Swansea Bay project suggested that the subsidy support level (or strike price) required by the project was in fact much lower, and potentially similar to the £92.50/MWh support level offered to Hinkley Point. However this is only possible by tweaking the parameters of the subsidy contract (known as the Contract for Difference), which includes the length of the contract, indexing rate and some form of Government grant.

Indeed, the evidence session highlighted that achieving a strike price of £92.50/MWh was contingent on receiving a grant from the Welsh Government of approximately £200 million. Without this, if Swansea Bay had exactly the same terms as Hinkley, with no extra government loans, it could cost about £150/MWh- far higher than £92.50/MWh but slightly lower than the initial £168/MWh.

Obfuscating the true cost, as well as a lack of transparency over financing Hinkley, serves to undermine public trust and confidence in decisions of national significance. Moreover, when it came to the lagoon, when compared against the dramatic cost reductions in solar and wind, the economics of the project looked even less competitive.

Creating a world beating industry?

Another challenge posed was the lack of competitive advantage – would the Swansea Bay project establish a significant export industry as claimed? One of the reasons that there has been ongoing interest in tidal is that the UK has amongst the best tidal resource in the world. Tidal range resources tend to be highly concentrated in very specific areas, where there is a large vertical difference between high and low tides. There is interest in developing tidal lagoons and barrages in a number of countries, but it is limited to a few countries with high tidal ranges such as Canada and India. If the UK wishes to become a market leader in low carbon technologies, then it might be better to focus on technologies with truly massive global potential – as it has done with wind.

The bigger picture – inconsistencies in Government policy

Perhaps a more striking feature of this whole debacle is the prevarication and inconsistency in governmental decision-making. Behind this lies a number of public, private and political pressures. If ever there was a textbook example of how to go about Government lobbying, then it is the Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon project. This in part explains why the decision over its future was so prolonged and why the debate lacked nuance.

Furthermore, the Government has tied itself in knots. While citing value for money – or the lack of – as the reason not to proceed with the lagoon, it has also overseen a ban on onshore wind – the cheapest form of low carbon energy (shown in the figure above).

To some extent, the debate of Hinkley vs Swansea also misses a bigger point- what is the best framework for supporting investment in low carbon technologies and what is the role of the state?

Efficient cost reduction framework: Competitive Bidding

Beginning with the framework, competitive bidding has proved instrumental in driving the cost of renewable energy. In the 2015 subsidy price for offshore wind was £114.4, but in 2017, winning bids fell far below predicted levels with 71 percent of all capacity clearing at £57.50/MWh. In just two years, the competitive nature of the auction saw prices fall by almost 50 percent. The successful cost reduction in offshore wind clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of competitive reverse auctions – and competition more generally – in delivering best value for money. Yet, Hinkley – and Swansea if it was successful- would have been awarded support without entering a competitive auction. If both Hinkley and Swansea had to bid competitively for support, it could have lowered the level of Government support. But there is also an argument that wind might not have achieved dramatic cost reductions without initial state support – which further illustrates inconsistencies in approach to nascent technologies.

Role of the state

In terms of the state’s role, nuclear power is always going to be developed by state-backed companies, not private companies : the cost and risk mean nuclear power has never been built without state support. One reason is that when the Government is both the supplier and purchaser then a steady pipeline of projects can be guaranteed, allowing the development of supply chains. But just as important as this is state financing. The high upfront cost of building a large nuclear power plant combined with the long time it takes to recover costs, means that the way the project is financed can make a huge difference to the cost. Prof Dieter Helm highlighted this in a recent paper in which he said there is a strong argument that if Hinkley had been financed by government backed nuclear bonds, the cost might have been significantly lower. This exemplifies the inherent tension between government support and technology neutrality which often manifests into inconsistent application of policy.

Swansea Tidal Lagoon shares similar characteristics to large nuclear plants, in that they are capital intensive and have a very long lifetime. As such, the case for direct state financing in technologies that share these characteristics is strong, so long as they can demonstrate that costs will fall with increased deployment. Aside from the economic case, one can speculate whether other drivers ultimately tipped the balance in favour of one technology over the other.

As always, the challenge is finding ways to limit the exposure of taxpayers and customers – as Swansea Bay found to its cost. Ultimately, while the case for and against specific projects can be debated, surely we all agree that applying a consistent approach and ensuring a level playing field for all technologies is essential.