The huge achievement

The advanced economies of the OECD principally concentrated in North America and Europe have now largely recovered from the macro-economic consequences of the credit crunch and the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. Market economies faced their greatest challenge since the Great Depression in the 1930s and in most respects policy makers did a pretty good job at stabilising economic activity and restarting economic growth.

Getting back to normal and getting on with it

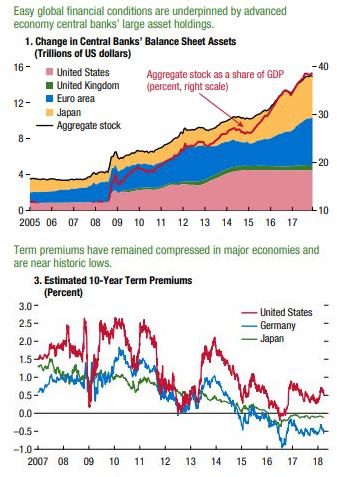

Central banks now have the difficult task of working out what is the new normal. This includes deciding where the present equilibrium level of interest rates should be and how they can shrink their massively expanded balance sheets, created as a result of the unconventional monetary tools mainly quantitative easing deployed during the financial crisis. They probably are a bit behind the curve in doing so and need to make progress with raising interest rates and withdrawing from asset markets. The two charts below taken from the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report: A Bumpy Road Ahead published in April illustrate these challenges. This would give them policy flexibility and begin to undo some of the complex micro-economic distortions created when interest rates are close to zero. There is also a recognition that expansionary fiscal policy has the potential to offer a material macro-economic stimulus, especially in more closed economies such as the US or if done in a synchronised fashion by several developed economies, as happened in 2009.

Central banks now have the difficult task of working out what is the new normal. This includes deciding where the present equilibrium level of interest rates should be and how they can shrink their massively expanded balance sheets, created as a result of the unconventional monetary tools mainly quantitative easing deployed during the financial crisis. They probably are a bit behind the curve in doing so and need to make progress with raising interest rates and withdrawing from asset markets. The two charts below taken from the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report: A Bumpy Road Ahead published in April illustrate these challenges. This would give them policy flexibility and begin to undo some of the complex micro-economic distortions created when interest rates are close to zero. There is also a recognition that expansionary fiscal policy has the potential to offer a material macro-economic stimulus, especially in more closed economies such as the US or if done in a synchronised fashion by several developed economies, as happened in 2009.

President Macron’s audacious agenda for the eurozone

Meanwhile, the politicians and technocrats that shape the eurozone are still wrestling with the fundamental questions of its function, purpose and institutions. The agenda of reform laid out last year by President Macron of France represents an audacious attempt to rectify its fundamental operational defect. Essentially a eurozone budget would be constructed with a finance ministry to match its central bank, thereby giving the monetary union both the monetary and fiscal arms of macro-economic policy. European economic and monetary union was first seriously suggested in the early 1970s at the high point of the Keynesian macro-economic consensus. The Werner report on monetary union was very much couched in the language and intellectual framework of Keynesian macro-economic demand management through fiscal policy.

The narrow conception of the single currency in its construction

In 1989 the Delors report that framed the monetary union eventually created in 1999 reflected the state of economic opinion prevailing at the time. With hindsight, at best this was a rather narrow and highly stylised interpretation of the then consensus on monetary policy. The focus was purely on the conditions for a nominal or financial convergence with conditions relating to inflation, exchange and interest rates and fiscal rules to curb potential free riders. The concern about moral hazard and the intellectual legacy of the Bundesbank meant that there was no provision of a lender of last resort function and a strict ‘no bail out’ rule. The fiscal rules, limiting budget deficits and public sector debt, made it difficult for individual economies to deal with the consequences of asymmetric economic shocks.

Flawed from the start

The EU’s politicians were wilful as they embraced a complex technical monetary project for political reasons. In the process they refused to take account the experience pf the German monetary union between east and West Germany, the consequences of which still shape living standards and economic activity in eastern Germany. They also pursued a social action programme of regulation that was expressly conceived as a means of limiting the competitiveness of Portuguese, Italian, Greek and Spanish workers. According to the then German minister for social affairs, this was to prevent ‘social dumping’ damaging the interests of German workers. So, at the very time that countries needed greater product and labour market flexibility within a monetary union the European Council proceeded to make them less flexible.

One interest rate and a single monetary policy will not properly work in a monetary zone that does not conform, at least approximately, to the concept of an optimal currency area. Few economies or currencies operate in a fully optimal currency context, but the creation of the eurozone stretched the challenge beyond the capabilities of the economic instruments that could mitigate if not remedy them. Fiscal policy, however ambitious, cannot remedy a radically defective monetary policy. For these reasons the Macron agenda would fail if it were to be implemented.

Italy, parallel currencies and the Bundesbank’s fear of inflation

In 1989 the UK Government’s response to the Delors report’s proposed single currency was the Hard Ecu alternative scheme. The idea was given short shrift by the UK’s then EC partners and crucially by the Bundesbank which feared inflationary consequences. But in 2018 the new Italian Government has come to office with a programme of spending plans and tax cuts that will challenge the eurozone’s fiscal rules and has expressed an interest in issuing Italian Treasury notes in addition to the euro currency in circulation. The Italian government that was about to be formed last week would have been on a collision course with the present institutional structure of the euro.

Time to have a plan for an orderly withdrawal procedure

A group of German economists led by Hans Werner Sinn and Jurgen Stark have not only dismissed the Macron agenda, but gone to the heart of the issue. They argue that the European Council in June should concentrate on shaping a structural reform agenda and one where the eurozone has ‘an orderly insolvency procedure for states and an orderly withdrawal procedure’. They note that President Macron’s agenda would aggravate the falling living standards that many European citizens, particularly the young, have faced.

Taking advice from the ECB’s economists about convergence through immiseration

The blunt truth is that neither a Single Resolution Fund nor a common deposit scheme would solve the fundamental economic problems any more than an ambitious programme of fiscal transfers across regions and countries. Economists at the ECB in 2009 published a paper The Role of Fiscal Transfers for Regional Convergence in Europe. They found that on average they impede economic growth, having a negative impact in the region that receives the transfer and an even greater impact on the regions that pay for them. The result is vividly expressed by the ECB economists as a process of “immiserising convergence”.