Today is the final deadline for university applications via UCAS. If previous years are anything to go by, over half a million hopeful applicants will have gone through the process of filling in their forms, making choices, completing personal statements in the hope of going on to an educational experience that will transform their lives.

But to what extent are these hard-working young people being well-served by the system? In Policy Exchange’s report last June, Sins of Admission, we set out how university admissions are having a detrimental impact on schools and sixth form colleges – and pupils in the process of applying for higher education. The increasingly routine use of unconditional offers and contextual admissions threatens to undermine the quality of our universities and feeds the soft bigotry of low expectations in schools.

Since our report was published new UCAS data has shown that the number of unconditional offers has risen sharply once again, with over a quarter (25.1%) of applicants receiving at least one unconditional offer. Of this, so-called conditional unconditional offers experienced the largest growth in 2019, increasing by 26.2%, despite the fact that these have been rightly condemned by Education Secretary Gavin Williamson and described by the Office for Students as ‘akin to pressure selling’. The Association of School and College Leaders has said these types of offers have “more to do with the frenetic scramble to put ‘bums on seats’ than the best interests of students” and has highlighted that those most vulnerable to such blandishments are likely to be those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The increasing use of contextual offers is also a cause for grave concern. It is, of course, uncontroversial to suggest that on a case-by-case basis, entry grades may be varied to take into account specific and exceptional circumstances. This, however, is worlds away from the approach where entry requirements are lowered across the board, and students are assumed to be less capable simply because of their family income or the colour of their skin. The evidence base supporting contextual admissions does not stand up to scrutiny. Notably, a paper by Boliver et al uses flawed statistical methods – taking the performance of a highly atypical subgroup (students with lower grades who are accepted to higher tariff institutions) to draw general conclusions about all students with lower grades – in support of its erroneous conclusions. This paper has been widely cited, including, unfortunately, by the Office for Students, to justify current policies.

As the Prime Minister has said, ‘Talent and ability are everywhere, opportunity is not.’ For this reason, the Office for Students has a statutory duty to promote equality of opportunity – and not, as some have misinterpreted it, equality of outcome. Schools such as Michaela Community School or the King’s and Exeter Mathematics Schools, as well as charitable organisations such as Generating Genius have demonstrated the truth of this, educating talented youngsters from all backgrounds to the highest levels of attainment. It is this approach that will deliver social mobility in higher education; by contrast, as former Education Secretary Baroness Morgan of Cotes wrote in the Foreword to our report, “The blunt tools we are using at the moment, including contextual offers, risk promoting low expectations for some of the most capable pupils in the schools system.”

But to focus on these matters, grave as they are, may be to miss the wood for the trees. The wider question is whether a system which sees ever more young people going to higher education, increasingly to full-time, undergraduate degrees, is one that serves the wider interest of the nation, the economy or indeed young people themselves.

The public think it does not. Polling last year showed that 45% of people think too many people are going to university vs 24% who think too few are, alongside strong support for increasing support for technical and vocational training. As is so often the case, the evidence supports the public view.

The evidence for this has been systematically documented in public statistical releases, academic analysis and in the popular press (for example, The Great University Con (New Statesman, 2019) provides a comprehensive view). The undergraduate drop-out rate has been steadily rising for several years and 34% of graduates are not in graduate jobs, consistent with a steady upwards trend of overemployment since 2002. The average graduate premium is in sharpdecline and a third of male graduates see no, or a negative, earnings premium. Grade inflation is out of control, with the proportion of firsts and 2:1s awarded soaring from below 50% in 2000 to 79% today and almost 50% of students receiving firsts at some universities – and yet the OECD finds that, in contrast to almost every other OECD country, young people are no more likely to have basic literacy and numeracy skills than those over 55 and that the mean numeracy and literacy of UK graduates is closer to that of a Dutch high-school leaver than a Dutch graduate. An increase in qualifications has not resulted in a commensurate increase in skills.

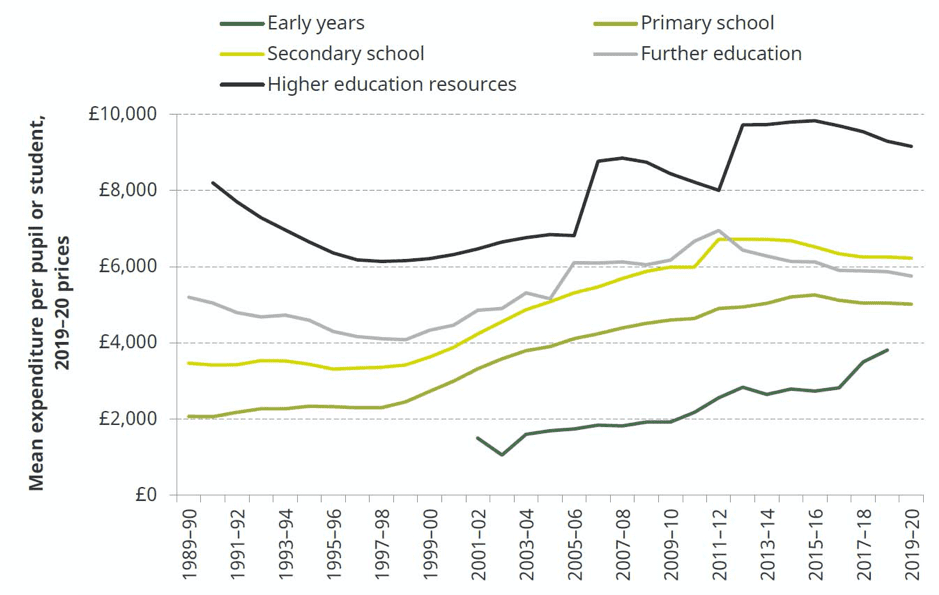

Over the last two decades, higher education has been promoted as the most desirable destination for young people. Ever since Tony Blair’s target of 50% of young people going to higher education, more people going to university has been seen as an unquestioned good. Funding has following intention, with mean expenditure per pupil for further education steadily losing ground compared to higher education – and even to secondary schools (see figure 1). Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in the increasing dominance of full-time bachelor’s degrees becoming the increasingly dominant as the primary mode of post-18 education, with a significant decline in the numbers in part-time study and in further education – participation in the latter plummeting from 4.8 million in 2010-11 to 3.6 million in 2016-17.

Figure 1: Mean Expenditure per pupil (IFS Annual Report on Education Spending in England, 2019)

The government should commit to a large-scale and whole-hearted rebalancing between higher and further education. This must entail the introduction of a sector-wide numbers cap on full-time undergraduate courses, alongside freezing tuition fees for the duration of this Parliament. This would ensure that future funding increases – and growth in numbers – can be devoted towards technical and vocational education, including apprenticeships, further education colleges, part-time learning and Ofqual-regulated Level 4 and 5 qualifications. Such a policy would not only command popular support but would be in the best interests of the nation – and would lead to the best long-term outcomes for young people themselves.