It is now seven years since the depths of the financial crisis, and given their average historical frequency, it is likely that we are now closer to the next recession than the last. As we come up to his eighth Budget, with financial markets looking increasingly jittery, how well has the Chancellor done at improving the resilience of the British economy?

Everyone will have their own way of defining economic security. There is no textbook answer to what exactly it means. Nevertheless, I think you can get a good feel for it by looking at three big questions:

How sustainable are government commitments on spending and taxation?

Many people think of fiscal sustainability in terms of the deficit, or from the other side, the interest rate markets demand for purchasing your debt. Ultimately, however, both eventually come down to the more nebulous matter of politics. It is always theoretically possible to close a deficit with sharp cuts to spending or increases in taxes, and this is especially true in a country with its own central bank and currency.

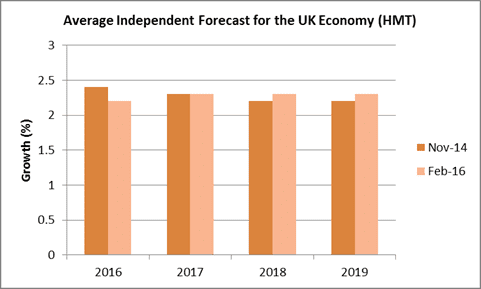

One way to minimise that anger is to set realistic expectations. In the UK, the Government’s new fiscal rule has been criticised as being overly strict and inflexible. This, however, is unfair for the sort of environment it has been designed for, one in which growth progresses steadily, which is overall still the situation we are most likely to face. While both the IMF and OECD have made modest downgrades to their world growth forecasts, both still believe that growth is likely to continue at about the 2% level. Independent forecasters , equally have shown no real change in their expectations of medium term growth. The widely reported ‘£18 billion hole’ in the economy is more a result of historically low inflation than slowing growth, with NGDP growth, a measure of demand, slowing sharply since mid 2014.

That is not to say that slowing demand is not a problem, and if the Bank of England doesn’t succeed in turning matters around, the Treasury will continue to face problems. Nevertheless, assuming that matters don’t get worse, changes on this sort of magnitude should not be enough to imperil either the economic recovery or the Government’s fiscal strategy, especially given the £10 billion margin the Chancellor left himself in the autumn. If the Government can afford to keep raising the personal allowance, or any of the dozens of other micro policies that typically fill a Budget, it can easily find ways to find the reported £4 billion that is needed to achieve the surplus. This is still only half of the £8 billion by which the Treasury eased the departmental spending envelope between last year’s Summer Budget and Autumn Statement.

This situation might easily change in the event of some big economic or political shock: perhaps a sharp downturn in China or further instability in the Middle East. A major recession which blew a hole in the Government’s fiscal plans would be hard to adapt to without further delaying the Government’s surplus target. Over the last year, the Chancellor has eased off significantly some of the more ambitious spending reductions originally pencilled in. Nevertheless, a Spending Review would be hard to unpick, large proportions of the state are now ring-fenced from further cuts, the Government has promised not to raise any of the major taxes and we are reaching the political limits of further reductions to welfare or local spending. Delaying the surplus target, on the other hand, wouldn’t be a disaster. Government interest rates remain low, and markets are likely to forgive further borrowing given the excuse of a significant recession. Nor would this break the letter or even spirit of the fiscal rules, which explicitly allow for such a postponement. On this front at least, the UK looks relatively secure.

How diversified is the UK economy?

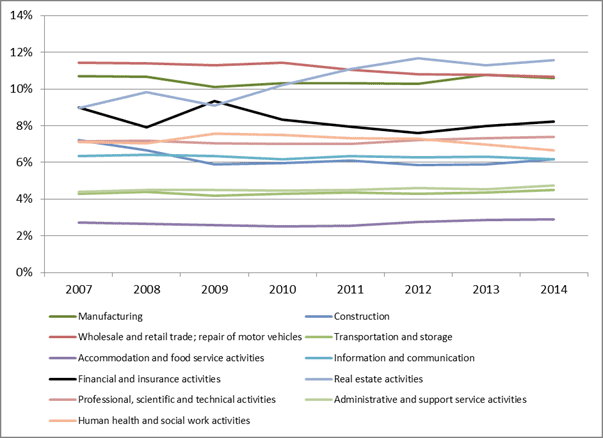

One reason the recession was so catastrophic for the UK public finances, with our deficit spiking far higher than in many of our European neighbours, was the disproportionate size of finance in our economy, and hence tax revenues. This is sometimes described as ‘rebalancing’ the economy – but I think diversification is a more helpful frame. There are often good reasons to be highly specialised in one activity, but the flip side of that is it inevitably leaves you exposed to more idiosyncratic risk.

In the long run, there seem to be good reasons to be relatively bullish on the UK’s ability to prosper in new industries. As a global hub, London keeps going from strength to strength, we are world leaders in emerging fields such as machine learning, and a generally friendly regulatory approach to new technologies from gene editing CRISPR to digital currencies like Bitcoin should keep us as the cutting edge. Britain’s world expertise is in exporting high end services, and this is not a bad place to bes in a world of a growing global middle class, or where much of manufacturing will only keep on being automated.

In the short term however, it has to be admitted, that there has been relatively little change in the overall structure of the UK economy. Finance and insurance made up 9% of the UK economy in 2007, and seven years and one financial crisis later in 2014 they are only a mite smaller at 8%. PWC estimates that the total contribution of the financial sector to UK tax revenues fell from 13.9% in 2006/7 to 11% in 2014/15.

While household debt to income ratios have been falling, the amount we borrow as a country – our current account deficit – remains pretty high at 5% or so of GDP. Our trade deficit in goods is at historically high levels, although much of this is counterbalanced by our strength in services. Instead, it has been the fall in income from weakening overseas investments that have driven much of the shortfall in our balance of payments.

The reality is that the fate of the UK economy remains highly entangled with the state of finance and the world economy in general. As Peter Thiel has argued, few cities are as levered against globalisation as London. This may simply be an unavoidable side effect of the sort of economy Britain is – one for which any cure world be worse than the disease.

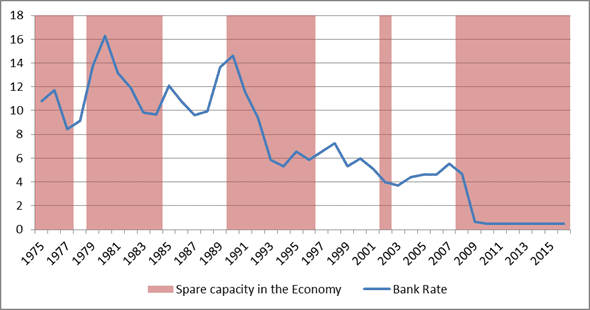

How much spare capacity exists at the Bank of England to fight a further downturn?

Given the constraints on public finance and the difficulty in completely flipping the structure of our economy overnight, inevitably much of the responsibility for fighting a future recession will rest with the Bank of England.

In the past, monetary stimulus has largely come via cuts to the central bank interest rate, which has then been allowed to slowly climb back upwards as the economy recovers. In today’s economy, interest rates remain stubbornly near zero, and the long worldwide trend of gradually falling rates suggest that even in an optimistic scenario they are unlikely to return to a more historically normal 5% level soon.

This will require the Bank to be more creative in the kinds of stimulus it uses going forward, but does not necessarily mean it is powerless, or even that close to running out of ammunition. Speaking to the Treasury Select Committee last month, Mark Carney argued that “considerable room” remained for further stimulus, although he ruled out ECB -like negative interest rates in favour of an expansion of QE or more aggressive forward guidance.

This is perhaps the most interesting – and neglected – argument in the UK macroeconomy at the moment. Some argue that standard QE is unlikely to be enough, and that alternatively we need to look more at either conventional fiscal policy or exploring more exotic options such as helicopter money. Others argue that the Bank is already more powerful than it realises, and it could do a lot of good simply by stopping all the talk of raising interest rates at a time when nominal growth seems to be slowing. Where you stand on this debate is likely to influence exactly how secure you think the UK’s overall macroeconomic position is.

Overall, the Chancellor has followed a fairly consistent economic strategy over the last seven years: slow reforms to improve the supply side and rebalance the economy; aggressively reducing spending while allowing automatic stabilisers to operate; relying on monetary policy activism to boost demand in the economy. There is no reason that this strategy should stop working, even if the UK does run into another recession or even crisis over the next few years.

Nevertheless, good security means being prepared. Both the Treasury and the Bank of England almost certainly have a contingency plan for what they would do if growth drastically dropped again – and it might boost confidence in the meanwhile, if they were a bit more open about what exactly it might look like.