Integration and the French elections

Nicolas Anelka had gone missing and so had we. The year was 1999 and Arsenal’s then-young star striker had disappeared. Meanwhile, the Norrie family holiday to France had gone awry after my father had taken a wrong turn and we had ended up in Trappes, a banlieue roughly one hour west of Paris.

I have a clear recollection of our car driving slowly through a busy throng of people; all were visibly from an ethnic minority. It was the first and only time I have been to a banlieue. These places do not attract tourists.

We looked at them and they looked at us. There was no hostility that I can recall but rather a gulf – the looks we were getting seemed to be saying who are you and why on earth are you here? We were just as perplexed – it was another France, far from the rural idylls we knew.

We eventually found our way back onto the beaten track. Arriving at our hotel, we turned on Sky News only to find a reporter broadcasting from of all the places in the world – Trappes – where Anelka was apparently holed up, it being his home town, and in the process of drawing his Arsenal career to a close.

Today Trappes has a population of around 32,000. Many are Muslim and of North African decent although it is impossible to say exactly how many due to France’s laws on data collection, which prevent counting people by ethnicity and religion. Unemployment stands at 18.9 per cent – almost twice the national average. It has a reputation for the teaching of hard-line Salafism. Between 60 and 80 have attempted to join Islamic State in Syria. Just last week, police arrested 4 people suspected of preparing terrorist offences.

Trappes became the focus of attention when in July 2013 angry youths battled with the police. The spark had been an incident where a young Muslim convert was involved in a violent altercation with police after they checked the identity of his veiled wife. France had banned veils in 2011. It is clear that there are deep integration problems.

France has changed considerably in its ethnic composition in recent decades, thanks to mass immigration. Data are hard to come by but it seems that in 2008, 19 per cent of the population were either immigrants or their most immediate offspring. 6 per cent are of Maghrebi origins, 8 per cent are European, with 2 per cent from sub-Saharan Africa. Immigration has been rising since 2013 and that rise is mostly fuelled by greater numbers of Europeans. As of 2016, it stands at 229,600 (gross); this is less than half the UK figure but still up by 18 per cent since 2013. 46 per cent came from Europe, 30 per cent from Africa, and 14 per cent from Asia. Unlike the United Kingdom, a greater share of immigration is from predominantly Islamic countries.

France has grown increasingly sceptical about immigration in the wake of terrorist attacks, most notably in Paris in November 2015 and in Nice in July 2016. On top of this has been the migrant crisis along with the growth and ultimate dismantling of the migrant camps at Dunkirk and Calais. Pew polling from 2014 found that a majority of the French wanted less immigration – 57 per cent.

Furthermore, an Ipsos Mori poll found 45 per cent of French people say that immigration is bad for the economy while 41 per cent say it has made it more difficult to get jobs. 61 per cent want all immigration from Muslim majority countries to be stopped.

Perceptions matter too. As is the case in most western countries, the French are likely to overestimate both the shares of immigrants and Muslims. According to Ipsos Mori, the French estimate the share of immigrants to be at 25 per cent. The same pollsters found that France was the country that most erroneously over-estimated its Muslim population. French people on average guessed the population of Muslims living in France to be 31 per cent, compared to an official estimate of 7.5 per cent.

Patterns of segregation are entrenched. 50 per cent of immigrants are living in the 10 per cent of neighbourhoods or cities with the most immigrants; this compares to just over 10 per cent of non-immigrants. For African immigrants alone the share is closer to 60 per cent. For second generation African immigrants, 50 per cent are clustered in the top decile of places as ranked by their share of immigrants. The Open Society Foundation reports that Marseilles is between 30 and 40 per cent Muslim, with this population tending to cluster in the poorer north of the city.

Nearly 40 per cent of all immigrants are in poverty compared to 10 per cent of natives; for Africans the rate is closer to 45 per cent and roughly twice that of European immigrants. Youth unemployment at 32 per cent for French-born Africans is twice the rate of the ethnic French.

France’s minorities come to feel French across generations but the process of absorbing into the national identity is not complete, leaving substantial minorities of minorities without a sense of belonging. 25 per cent of immigrants feel French; on a separate measure, 51 per cent feel at home in France. Amongst the second generation, 63 per cent feel French while 69 per cent feel at home in France.

The other side of integration is the extent to which the established majority are prepared to accept newcomers. 30 per cent of immigrants to France and 43 per cent of the 2nd generation claim they have experienced racism. 45 per cent of immigrants who have become citizens say they have been rejected as French while for the second generation it is 36 per cent.

Immigrants are much more likely to be actively religious. Perhaps though the greatest barrier to integration comes from a resurgent religiosity that is at odds with the liberal secular mainstream. Research by Algan, Landais, and Senik found that Maghrebi 1st generation immigrants were more likely to take part in religious services with some evidence of a decline in the religiosity of the 2nd generation. However, what is most notable is that there is evidence of greater religiosity among younger cohorts – a second generation Maghrebi born before 1970 is no more likely to take part in religious ceremonies than an ethnically French native. However, a second generation Maghrebi born after 1970 is significantly more likely to do so.

The Institute Montaigne has estimated that 46 per cent of Muslims in France are “completely secularised or approaching full integration”. 28 per cent are however estimated to be living parallel lives, whose views “suggest a tendency for withdrawal and separation from the rest of society” and for whom “Islam is a means of self-assertion at the margins of French society”. It is this latter group that is the most likely to be unemployed. (Note that the remainder are in between these two groups). Extrapolating, this would give us roughly 2.3 million Muslims that are very well integrated and 1.4 million poorly integrated.

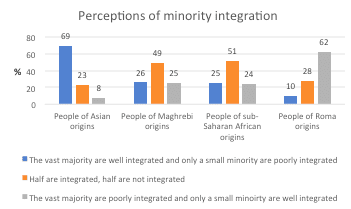

French people regard some groups as being better integrated than others. As seen in the graph below, it is the Roma that are regarded as the least integrated – 62 per cent regard the majority as not integrated. Asians are regarded as the most successful – 69 per cent say the majority are well integrated. For Maghrebi and sub-Saharan Africans, 50 per cent say that half are integrated, half not, while 25 per cent think the majority are poorly integrated.

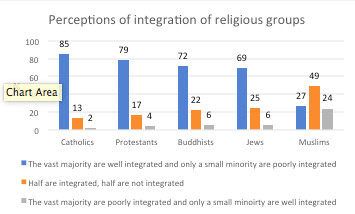

Looking now specifically at religious groups, it is only in the case of Muslims that there are substantial doubts about integration. 49 per cent say half of Muslims are poorly integrated while 24 per cent say the vast majority are not integrated.

At the last presidential election in 2012, France’s Muslim population backed Francois Hollande, with 86 per cent voting for him. As of yet, no studies of how the vote broke up by faith or ethnic group are available. However, we know that the Socialists vote has collapsed overall so many Muslims will have switched their support. Failure to deliver on promises to improve the situation in the banlieues will have exacerbated this. We also know that many of the most prominent banlieues tended to go for the hard-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon. For instance, Clichy-sous-Bois backed him with 35.9 per cent, as did Bondy (34.5 per cent), and so too Trappes (32.6 per cent).

It is clear that in France today there are deep anxieties not only about immigration and integration but also the manner in which the country is being reshaped. It is Marine Le Pen that the French are most likely to entrust with bringing about solutions to France’s immigration problems. According to Ipsos polling, 42 per cent regard her as the best placed candidate on immigration compared to 18 per cent for Macron. She has set out a hard-line agenda of cultural protectionism that resonates with many.

Macron knows there are integration problems and he has made policy proposals to address them. He has affirmed France’s laicité (as has Le Pen) and wants to give all religious leaders training in secular values, but rejected further bans on religious clothing, and has promised government subsidies for companies that hire people in low income neighbourhoods. He has also made combatting discrimination a priority. All this is sensible as it serves to bring France’s minorities closer into the national mainstream.

He also advocates making the ability to speak French the principal condition for getting citizenship. Some critics says this sets the bar too low – many immigrants are coming to France being able to speak French already as they come from Francophone countries. It will do nothing to reassure the anxious ethnic French majority that their existing culture is to be renewed rather than relegated into just one option among many. Furthermore, his statement on the French Algerian conflict being a “crime against humanity” put him at odds with much of the white French population, identifying him as part of a distant liberal elite.

Le Pen by contrast takes a much harder stance, pledging to suspend all immigration temporarily before limiting it to 10,000 per year and to deport all foreign criminals and foreigners with Islamist links. Rather than promoting integration, she stands for assimilation of immigrants through teaching of traditional French culture and enforcing of secularism and the French language. While she professes to stand for all French, her assimilation policy will further alienate many among minority populations potentially setting back what integration there is.

Macron looks set to win the presidency more due to the fact that he is not Marine Le Pen rather than because he is Emmanuel Macron, as he takes over the votes of those who previously backed other candidates. However, anxieties about integration are not going to go away. It is down to Macron to find some sort of bridge between his own cosmopolitan instincts and a communitarianism that needs to be incorporated into France’s politics. A failure to do so will only serve to store up problems for later.