Yesterday’s announcement that the cap on local authority borrowing for the building of new homes will be removed is welcome. As the Prime Minister outlined in her speech to the Conservative Party Conference, “There is a government cap on how much can borrow against their Housing Revenue Account assets to fund new developments… It doesn’t make sense to stop councils from playing their part in solving . So today I can announce that we are scrapping that cap.”

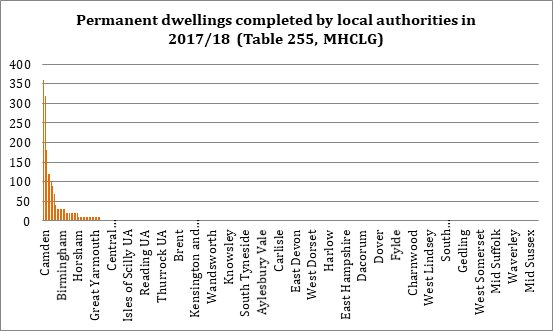

The announcement is welcome because local authorities have yet to play a significant role in directly tackling the crisis in housing supply. MHCLG figures show that last year just 1,870 new homes in England by local authorities with powers and responsibilities for housing (i.e. district and unitary councils). More than two thirds of these were built by just six local authorities – Camden, Stockport, Nottingham, Harrow, Ealing and Telford – while 288 local authorities with responsibility for housing of 326 built no new homes at all. Some local authorities have set up arms-length commercial housing companies, but it has been reported that, as of February this year, they had delivered only 528 homes across the country and only 35% of these were ‘affordable’.

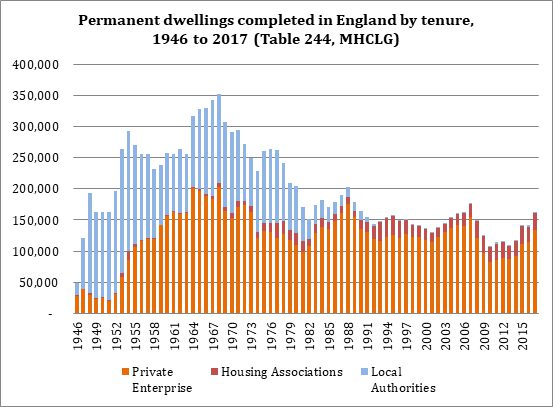

Compare this to the three decades after the Second World War, when English local authorities were building hundreds of thousands of new homes every year, and we can see a major reason why not enough new homes are built today. While housing associations are building around 25,000 new homes every year, there remains a significant gap between the supply of social housing and the need for social housing. Figures from MHCLG show over 1.1 million households are on local authority housing waiting lists in England. A significant number are also living in temporary accommodation that is often inappropriate and of poor quality.

It is in this context that giving local authorities greater freedom to finance the building of new homes through their Housing Revenue Account (HRA) is a breakthrough in government policy. Research by Savills in 2017 found more than four in five local authorities with an HRA were operating their business plan within 20% of the HRA debt cap. By providing local authorities with greater capacity to borrow, they will be able to finance more new developments. This point was made at one of Policy Exchange’s housing fringe events at Conservative Party Conference earlier this week. Bob Seeley, MP for the Isle of Wight, argued that his council is prevented from building the homes they know islanders need because of a lack of finance.

Yet, as welcome as the announcement is, it raises a number of issues that Government and local authorities will need to contend with if the policy is to be successful.

Firstly, the large majority of local authorities are simply not set up for the large-scale construction of housing any more. Just 38 local authorities, mostly urban authorities but some of which are rural, built any new homes last year. Almost a third of local authorities don’t even have an HRA to borrow against (because they have transferred their housing stock to housing associations). This limited experience and expertise in building homes – which, after all, is a complicated business requiring appropriate sites for development, the securing of planning consent, the procurement of design and construction etc. – means that it could take a long time for councils to take full advantage of this new borrowing freedom.

Secondly, while one barrier to local authorities building new homes has been removed, many still remain. One barrier, for instance, is that building homes requires a huge amount of will and ambition. Many local authorities will not choose to divert resources away from managing other pressures like social care services.

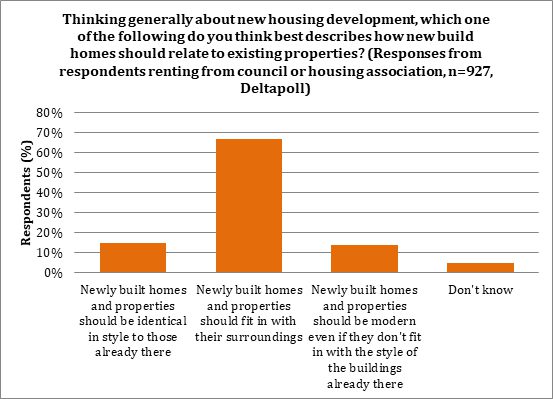

Another barrier is that council leaders, however ambitious, will continue to come up against councillors and a general public who oppose the building of new homes in their areas. NIMBYism is often justified – a point made by Tom Tugendhat MP at another of our housing fringe events at Conservative Party Conference where he argued there is nothing wrong with wanting to protect the asset you have worked hard to own. But as polling for our recent Building More, Building Beautiful report found, building new homes in designs and styles that are popular is a large part of the answer to overcoming this NIMBYism. Even if new social housing is typically designed and built to a standard as good as, if not better, than the private market, many people continue to associate ‘council houses’ with poor build quality and building styles they do not like. To therefore secure the support of communities for new social housing in their area, local authorities should aim to build new homes in popular designs and styles and in harmony with their surroundings. As the Prime Minister said last month in her speech to the National Housing Federation, “As you look from building to building, house to house, you should not be able to tell simply by looking which homes are affordable and which were sold at the market rate.” Our polling, illustrated by the graph below, shows this is what social housing tenants want too.

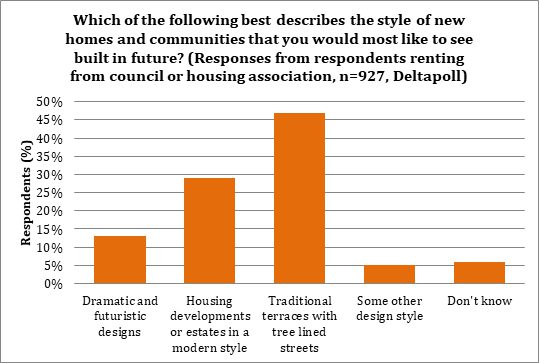

The polling also shows social housing tenants tend to want new homes to be built in a traditional style, as illustrated by the graph below.

Thirdly, there is the issue of how much money local authorities will actually be able to borrow against their HRA – and the extent to which that money can be used for a large increase in housing supply. There are a number of questions. How much can a local council borrow prudently against its HRA housing stock when its present social use value will be very different from its open market use value in terms of credit risk? To what extent does past borrowing and historic debt impact their capacity to borrow now? With around two thirds of the 3.9 million households who socially rent also recipients of housing benefit, how much debt will rental revenues be able to service when there are limited means to increase those revenues without implications for the housing benefit budget of DWP? Furthermore, with HRA borrowing also used to finance the repair of existing stock, will the first port of call for local authorities be repairing dilapidated stock or additional building?

In conclusion, yesterday’s announcement is a step forward for government housing policy. It means local authorities will be able to build more homes for those who are less well off and who cannot afford the private market. In the long term, it is also good for public finances, with more public money invested in new homes rather than being spent on housing low-income families in the private rental sector. Yet whether this leads to a step-change in the delivery of new council housing and whether that step-change is best delivered through borrowing against the HRA is a matter that we will only be able to answer in years to come. Let us hope that answers to some of these questions are provided in the Budget at the end of the month.