The European Central Bank (ECB) last Thursday announced that it would continue its asset purchase programme, buying €60bn a month of bonds to support the Eurozone economy. Most analysts expect the rate of purchases to slow and ultimately end some time next year. The ECB has already bought €1.3trn of bonds over the last three years of its quantitative easing programme. The exceptionally easy monetary policy of the ECB is now working at last with increasing evidence of an economic recovery. GDP growth in the euro area was at an annualised 2 per cent in the six months to March. This is strong growth – trend growth (the rate at which the economy can grow without generating inflation) is around 1 per cent a year in the euro-zone. Money growth has picked up to a healthy clip approaching 5 per cent a year. Private sector credit growth has stopped contracting and is now rising at a modest 2 per cent a year. Inflation is still subdued especially when the effects of recent energy price rises are discounted. It will take some time to reach the ECB’s “below but close to 2 per cent” inflation target, even with sustained economic growth. Asset purchases and ultra low interest rates will persist for a while yet.

Euro-zone economy heading into a “sweet spot”

The euro-zone economy is entering a “sweet-spot” in the economic cycle, where spare capacity permits a period of strong growth without incipient inflationary pressures. But a cyclical recovery will not alter the underlying structural weaknesses of the euro-zone. These are many and various and well documented. But the crucial fault-line can be summarised as widely disparate economies locked into a monetary straightjacket compounded by limited fiscal flexibility. This resulted in the countries of southern Europe deflating their economies amid severe austerity in order to regain lost competitiveness. Rather than the convergence anticipated by proponents of the single currency at its inception there has been divergence. In the periphery of the euro-zone this manifested itself in the form of large current account and public sector deficits – as well as falling output and employment.

Banking sector still a major risk to the Euro

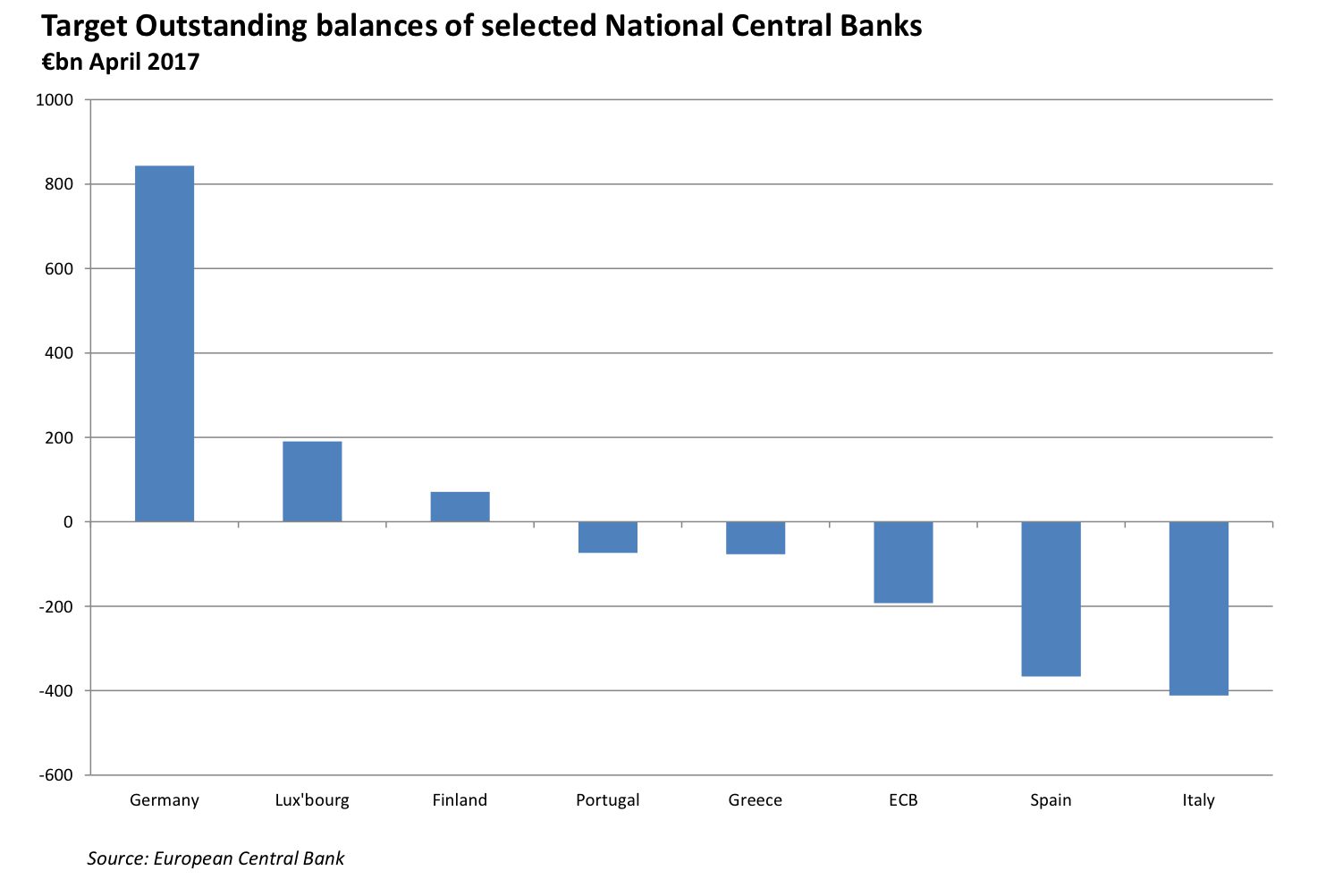

Bail outs and economic austerity were the result of the boom and bust of the first 15 years of the euro. These strains may have abated somewhat, especially as the euro-zone as a whole recovers – but they are still there. An area of increasing concern is found within the balances contained in Target 2. This is the cross border payments system for the euro-zone and includes the ECB and all the member country central banks as members. Target 2 – through the provision of unlimited central bank credit – has enabled central banks in some euro countries (mainly Germany) to provide credit to other euro countries suffering capital or banking outflows. Target 2 balances may at present partially reflect the shifting of bank deposits between member countries. In April Italy’s Target 2 position was a record negative of €400bn, while Spain also had a significant negative balance. (See chart below.) Banks in Italy and Spain are under pressure at present with continued concerns about systemic risk arising from large bad loans. Recent problems at Banco Monte del Paschi (Italy) and the rescue of Banco Popular by Santander (Spain) highlight the wider problems in these banking sectors. The “beneficiary” of these banking flows has been Germany – or more precisely the Bundesbank. If any debtor country were to leave the Euro and declare insolvency Germany would bear a large proportion of the losses. The incentive among central banks is to keep these balances growing since crystallization of these debts would lay bare the truth that as things stand Germany is ultimately the guarantor of the euro project.

The euro area needs reform and a benign economic backdrop is the best environment in which to do this. Unfortunately history suggests that reform occurs only in response to a Euro crisis. It would be a major new development if reform took place with no ongoing crisis as a backdrop. Successful monetary unions such as in the US combine labour mobility and fiscal transfers as alternative adjustment mechanisms for regions in the absence of monetary policy. The euro area has neither at present: cultural and language barriers suggest that labour mobility is unlikely to emerge any time soon. Reform ultimately will have to incorporate an element of fiscal union. But no matter the degree of labour mobility or fiscal transfers the euro area is a woefully inadequate monetary union: its various economies are structurally very different and at widely different levels of income. No sane economist would ever recommend forming a monetary union among its current members.

Germany boosting spending would help

But another reform is also necessary and this is one that does not require a new Treaty. Germany needs to spend more and save less. President Trump misses the point when he lambasts Germany in effect for exporting too much and running a large trade surplus. But there is an element of truth in the charge. Germany’s trade surplus is more a case of importing too little through restricting domestic demand. Germany’s current account surplus has averaged over 7 per cent of GDP a year so far this decade and last year was no less than 8.3 per cent of GDP. A shift in policy towards greater spending would provide a sustained boost to demand for Germany’s euro-zone trading partners helping them to recover and rebalance their economies. It would also deal with (one of) President Trump’s criticisms of Germany.

Political union necessary to save the Euro

Monetary unions do not survive unless they become political unions too. This is well understood in European capitals and within euro-zone institutions. The new French President, Emmanuel Macron, has argued for a euro-zone budget, Finance Minister and separate parliament formed of the MEPs of the 19 euro member countries. This is indeed the political union that will ultimately be necessary to save the single currency. But such proposals do not find favour in Berlin where debt mutualisation i.e. German taxpayers guaranteeing the debts of other euro members, remains anathema. The political union issue is probably in abeyance until after the election in Germany in September. But there is no doubt that the issue will return.