Emerging middle classes around the world are putting the pressure on the UK to think about how it handles waste. It should invest in innovation to become a world leader

In the UK we think of ourselves as world-leaders in setting environmental standards. In many ways, we are. But a badly kept secret is that we, like many of our neighbours and developed-world counterparts, have a tendency to grasp the low-hanging fruit, while exporting more difficult problems.

Recycling is a prime example, with the UK sending two thirds of its ‘recyclable’ waste offshore. Whilst an efficient global market moves raw materials around, the global recycling system has resembled less a market and more a conveyor belt, carrying away anything considered too hard to handle at home. Yet we may be seeing the emergence of long-term trends that turn the system on its head.

On 18 July 2017, China notified the World Trade Organisation that it would no longer accept low-grade wastes from other countries by the end of that year. The notification explained:

“We found that large amounts of dirty wastes or even hazardous wastes are mixed in the solid waste that can be used as raw materials. This polluted China’s environment seriously. To protect China’s environmental interests and people’s health, we urgently adjust the imported solid wastes list, and forbid the import of solid wastes that are highly polluted.”

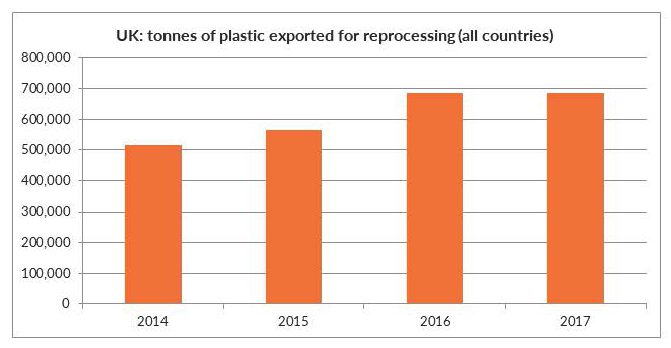

China’s move is understandable. UK households alone ship about 200,000 tonnes of plastic per year to China. In the five years leading up to the ban, the UK shipped 2.7 million tonnes of plastic waste there. It has been a massive release valve for a nation currently unable to manage its own wastes. But it’s estimated that just 9% of the 6.3bn tonnes of plastic made since the 1950s has been recycled, whilst 12% has been incinerated. The rest goes to landfill or finds its way into the natural environment. The Yangtze river carries 1.5m tonnes of plastic waste out to the oceans each year.

Source: The Environment Agency: National Packaging Waste Database

Source: The Environment Agency: National Packaging Waste Database

Almost overnight (though there were earlier signals), China refused to accept any more low-grade yang laji “foreign garbage”. So waste mountains started piling up in North America and Europe.

The result has been mostly chaotic. Warehouses, incineration, landfill and dumping have been the main outlets. Heads have been scratched across the Western world as waste managers, too used to exporting their least valuable materials, scrambled to find places to put previously exportable plastics.

Lord Deben, the former environment secretary, told Greenpeace that “European recyclers demand a standard of basic materials which is higher than the standard of things that can at the moment be exported”. Now that’s changing, but the UK and EU were caught unprepared.

“Europe basically didn’t have any plastics processing capacity,” one waste manager told Policy Exchange, “because China was doing it all so cheaply.”

DS Smith, a packaging company, last week spoke of “a creaking recycling system that is nearing overload,” citing years of “chronic underinvestment,” just as online shopping causes a boom in demand for packaging.

Until 2017, China was taking the West’s supposedly recyclable waste – mostly plastic and pulpable materials like paper and cardboard. It then repurposed them and sold them back to us.

Yet it was also accepting wastes that you can’t do much with. From low-quality, hard-to-recycle stuff like plastic bags and cling film, to contaminated, badly-sorted or mislabelled materials, the West was offloading what it couldn’t – or didn’t want to – deal with.

So, while we like to pat ourselves on the back for banning plastic straws after seeing them stuck up turtles’ noses, the bigger driver for change is a fundamental shift in the structure of global markets.

Around the world, huge middle classes are emerging. Very often they are younger than their counterparts in the West. And when a nation’s middle classes get bigger, that means two connected things for the environment. First, they have more economic options, so they feel less pressure to be the world’s binmen. Second, this increase in wealth creates more free time, more vested interests in local resources and (usually) more political empowerment. There is also usually an increase in consumption (though not necessarily at a rate to match our own), creating further waste system challenges at home. The result is that they won’t accept waste mountains, incineration and dirty rivers any more.

China’s size and political structure mean that sudden decisions can take much of the world by surprise, creating juddering effects. Yet the trend towards middle classes mean that India, South East Asia and Africa – all recipients of Western wastes – are likely to begin making similar moves.

Our response therefore cannot be based on finding new destinations to dump our plastic waste. Malaysia and Vietnam have seen a massive uptick of waste imports, but sooner or later they’ll get sick of them too.

We have to adjust to managing our waste better at home.

The big adjustment

The issue is about the quality of waste. The ‘garbage in, garbage out’ adage isn’t far off: if you send low-quality things into the waste stream then you’ll get low-quality outcomes. A more careful approach means we could extract real value and minimise the volumes going to landfill and incineration. If you can effectively separate wastes into their basic materials (e.g. removing labels from PET bottles and splitting up compound materials), they can be processed properly and reused.

But the market for quality waste has been undermined by a lack of consistency, a lack of scale and a lack of demand. Disparate approaches to waste among local authorities and the outsourcing of waste management to other countries have made it hard to build a coherent, innovative system that places a value on good quality waste.

China complained of contaminated waste. Therefore DEFRA’s proposal to mandate separate waste bins across the UK, with a core set of materials that everyone can have collected, is worthwhile. Inconsistency across local authorities has long undermined the ability of the waste sector to create economies of scale. It will help to sort our wastes into the correct streams at source. It could also make possible a better system of labelling (a key recommendation from Policy Exchange’s 2017 waste report), as it will create an element of consistency across councils.

But the really tough stuff is about product design. How do you remove sticky labels, clean food containers, split up the various compounds in a milk carton, strip off the plastic film from the top of a ready meal tray?

First, you design them better in the first place. Prevention is better than cure. DEFRA’s plan for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) could create both a carrot and a stick to create innovative solutions.

Producers and/or retailers of plastic products will be expected to pay for the full lifecycle of a plastic product. That will put pressure on giants like Coca Cola and P&G to package more intelligently in the first place, then steward their products towards reuse and effective recycling. The EPR principle moves us closer to the “resource productivity” that Policy Exchange recommended should sit at the heart of a post-Brexit waste policy.

EPR could also help to pay for innovations such as Ørsted’s Cheshire-based REnescience plant, which uses an enzymatic ‘wash’ to clean organic materials from plastics, raising the quality of plastics being introduced into the recycling system. The facility reduces the onus on washing, separating and sorting at source (aka your kitchen). As a result, less water is used in homes washing off food residues, hybrid products are broken into components, plastics are more easily sortable into the right waste streams and the company can even use the digestate left over to create natural gas for energy. Such innovations should be recognised by DEFRA’s new kerbside collection system, with councils able to use them instead of simply relying on households to do the work. However, EPR should be effective at boosting investment in such innovative facilities.

Another headline-grabbing proposal by DEFRA might not fit as well with this focus on quality and innovation. Its proposed deposit return scheme would make consumers pay a deposit on certain packaging, to be refunded when the item is returned after use. It runs the risk of diminishing the revenues of collection and sorting companies, which are the most likely organisations to make investments into an upgrade of our recycling system. Clever technologies don’t come cheap; they depend on reliable revenue projections for their financing, which the deposit scheme could undermine. The expansion of New York’s similar deposit scheme is meeting resistance for the same reason.

A global market

Moving things around the globe isn’t ideal, but it can lead to greater efficiency when averaged across a supply chain. The UK doesn’t have a vast manufacturing base like China’s, so moving useful raw materials such as recycled waste closer to their point of use can make sense. But it doesn’t make sense to send unusable waste and, as we’ve seen, countries are less likely to accept it.

DEFRA is moving in the right direction on improving the quality of our wastes, but there are some options for the next phase.

First, manufacturing sectors of all stripes should be moving towards a carbon accounting system that recognises and disincentivises ‘embodied carbon’. That is, the carbon emitted in the sourcing, transporting and manufacturing of a product. Policy Exchange’s 2017 report on waste reform recommended a role for carbon accounting, quoting an earlier government strategy: “in many cases, carbon acts as a good proxy for the overall environmental impacts of waste”. That is particularly relevant in the context of offshoring. If they had to factor in the carbon cost of sending waste to Asia, managers would think twice. They would be incentivised to send only that which carried real value for reuse. Used more broadly, it might also drive the shipping industry – a laggard on decarbonisation – to work harder on emissions. Britain is the home of the International Maritime Organisation and Lloyd’s of London and could take a leading role in driving that conversation.

Second, we need to make innovation easier among British waste managers. We have superb universities and engineers. By boosting capital allowances for innovative technologies like the REnescience facility, we would help the sector to exploit the economies of scale created by DEFRA’s new Waste and Resources Strategy much faster. Traditional waste sorting hasn’t worked well – time to let the robots have a go.

There is an opportunity for British businesses here. Growing middle classes in Asia and Africa won’t just stop accepting our waste mountains – they’ll be making their own too. They will increasingly have need of high-tech systems and know-how to manage their own growing consumption. This is why it’s as relevant to DIT and BEIS as it is to DEFRA. Britain could regain a leadership role by creating the technologies for a cleaner world.