The 2017 Budget Statement comes amid higher-than-usual fears that the axe is about to return to defence. This Government will be keen to allay any such fears, particularly given the latest bout of concerns about the decline of British influence, and the sharpening of knives for “irrelevant Britain”. It will also be loath to be seen to do anything that backtracks on one of the big gains of the 2015 budget (when then Chancellor George Osborne made a headline of reaffirming the NATO commitment to spend a minimum of 2% on defence).

Since the Strategic Defence and Security Review of 2015, seen as a great improvement on the 2010 version, the mood music on defence has improved. In recent months, however, new concerns about defence capabilities have become tied up with the narrative of the Brexit debate. Inevitably, the government faces questions as to whether there is a capability gap in its aspirations to play an expanded international role under the banner of “Global Britain”.

There have been repeated rumours in the press that the Royal Marines are likely to experience a reduction in numbers under the ongoing National Security Capability Review. For now, press rumours about specific capability cuts have been denied by the MoD. Any significant changes will be delayed until after the budget. Initially scheduled for December, the National Security Capability Review will now report in the New Year. This will give the new Defence Secretary, Gavin Williamson, more time to consider its potential implications.

It is important to note that unlike most defence-resourcing policy battles since 2010, this time the focus is more on capability rather than meeting the top line target of 2%. The Government is committed to meeting the 2% of GDP spending target (it is spending 2.14% this year) and increasing the defence budget by at least 0.5% above inflation throughout this Parliament. The budget has been on an ascending path since early 2016 when total defence spending nudged above the £35bn-mark. Key capabilities such as carrier strike and maritime air patrol are being reconstituted – if not necessarily at the pace and level that some would hope. The latest MoD statistics show that the department spent £35.3bn for 2016/17, with the total for the current year set to reach £36bn, and then projected to rise to almost £40bn by 2020/2021. Major, high-tech equipment programmes – including the future Dreadnought nuclear deterrent that will replace Trident – have been agreed for all three services and are in various stages of procurement under the £178bn Defence Equipment Plan, stretching out to 2026.

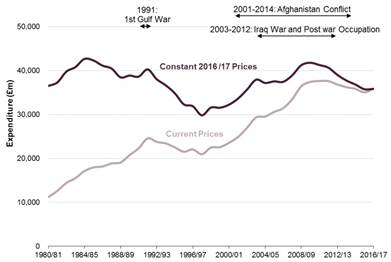

UK Defence Expenditure 1980/81 to 2016/17 (source: MoD statistics)

Figures presented in the chart are Cash Figures until 2000/01. From 2001/02 onwards the Net Cash Requirement has been presented. Conversion to constant 2016/17 prices uses the latest available forecast GDP deflator series published by HM Treasury dated 03 July 2017. All historical data are sourced from UK Defence Statistics Chapter 1 or, more recently, from the Departmental Resources Statistical bulletins. This chart includes expenditure on Conflict Prevention.

Figures presented in the chart are Cash Figures until 2000/01. From 2001/02 onwards the Net Cash Requirement has been presented. Conversion to constant 2016/17 prices uses the latest available forecast GDP deflator series published by HM Treasury dated 03 July 2017. All historical data are sourced from UK Defence Statistics Chapter 1 or, more recently, from the Departmental Resources Statistical bulletins. This chart includes expenditure on Conflict Prevention.

The Equipment Plan is certainly under serious pressure, but even so, the picture compares well to many other NATO member states. France, for example, has a poorer and run-down military (a €32.7bn budget for 2016/2017, or 1.78% of GDP, according to the French MoD), with its Chief of Defence Staff painting a grim picture in the Assemblée Nationale earlier this year and emphasising that in terms of equipment the French forces are “at breaking point”. Furthermore, Paris is only now beginning the decision-making process for renewing or updating key capabilities including nuclear deterrent or carrier strike; Britain, by comparison, is ahead in this respect.

Behind the dry statistics of UK defence, decisions have also been taken to seek competitive advantage in high-end, niche military capabilities – particularly in ISTAR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance), drones, air transport, anti-submarine warfare, cyber, or special forces. In a number of recent conflicts involving the UK, such “enablers” have proven increasingly critical to tactical success on the battlefield, particularly against non-state actors. Another growing area of niche UK specialism is “defence engagement” – training and building capacity in partner countries – which is now a core MoD goal. The calculation here is that engagement is becoming to long-term strategy what logistics are to field operations: an essential component of success.

This is not about painting a rosy picture of UK defence. There are many inadequacies that need addressing urgently. The risks of a “hollow force” are real and mass remains critical for battlefield effect, as well as for deterrence purposes. But ultimately quantity must be balanced against quality, and the rapidly changing modes of modern warfare – driven by changing threats and increasingly sophisticated weaponry – put a premium on staying at the cutting-edge of military technology and practice. What is more, the sharing of key military technologies further reinforces the special military relationship with the United States.

It is often said that the 2% defence spending commitment is symbolic but that is part of the point. With American observers increasingly concerned about the capability issue, as well as the top-line commitment, the UK must remain highly conscious of the signals that any adjustment in defence policy sends, particularly to Washington. The American military’s perception of British prowess is an important consideration in preserving the UK’s geopolitical standing. As some of the most senior figures in the US administration have made clear, things such as Air Chief Marshal Sir Stuart Peach’s election to the Chair of NATO’s Military Committee – the most senior uniformed role in the Alliance – are a recognition of the example set by Britain in NATO. Such influence is easily lost if that example is not sustained.

So Policy Exchange’s ask of the Chancellor – rather than simply more cash – is to signal a commitment to strengthening Britain’s armed forces into the medium and long term. He should use the Autumn Budget to restate the UK’s determination to be a strong, willing and able partner, both in quality and quantity.