Air Marshal Edward Stringer (Ret’d) CB CBE

Senior Fellow

“Statecraft” featured heavily in the annual Chief of the Defence Staff’s (CDS) lecture to RUSI. It is a term that is difficult to define precisely but we know it when we see it. For the purposes of this article it is defined as an appreciation of the long-term, animating factors of the geopolitical arena combined with a will and ability to maximise national and allied power to deal with them. It is the ability to make trade-offs in the interest of tomorrow. In its identification of the threats facing us the speech was a correct litany of the challenges we face – minus one, addressed below. In its assessment of what we are doing about it though, our statecraft in action, it displayed a certain complacency.

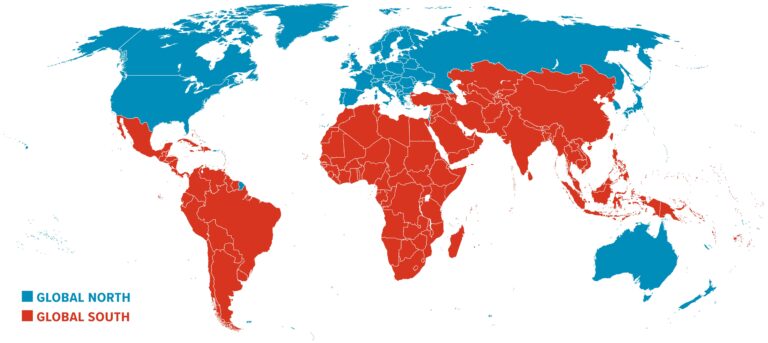

The picture of a worryingly unravelling World doesn’t need rehearsing here. Every continent manifests a series of crises. Not least in our own, European backyard where a major war rages and some commentators are now asking: ‘is Putin winning?’ CDS was right to outline that across the globe and at home democracies face a ‘full court press’. He could, however, have made more of the organised nature of the challenge posed by this de facto alliance of fellow-travelling autocrats. Especially, perhaps, of the role of Iran, which is now something of a lynch-pin in organising and supporting the range of distractions – most recently disrupting Red Sea shipping – that ultimately benefits Russia and China. How we might deal with these crises as an integrated problem would have made for a more interesting speech.

The missing concern was climate change. In itself a cause of instability, it is also driving fundamental change to our socio-economy. It would have been useful to hear from CDS how the military plans to recreate itself around the post-hydrocarbon energy economy that various international treaties have committed us to building in short order. This fundamental transformation of how the military powers itself will make the Royal Navy’s transition from sail to steam look like a battery swap.

But it is in the reassurance that CDS gives that we are all over these challenges that one senses a whiff of complacency, that something fundamental has been glossed over. The list of equipment programmes on which we are expending vast sums does, indeed, look reassuring; but could they be but another iteration of an expiring paradigm? Buying better, but very expensive, sails as the world transitions to steam? One example will suffice.

Within the Ministry of Defence are excellent people working with industry and the Ukrainians to furnish them with a proportion of the drones they need. That is currently a total demand of around 10 thousand drones a month, of varying levels of sophistication. We have generated, ad hoc, a force-development eco-system that works iteratively and rapidly inside Russia’s ability to produce counter-measures. ‘Good enough’ is good enough, and dual-use (civilian to military) technology is common. The battlefield provides the laboratory, and so this has become known as ‘prototype warfare’.

As a concept it is not totally new, all wars of the 20th century similarly saw scrambles to win technology races. This eco-system is producing drones in weeks, built in their hundreds, that cost several thousand each (whether measured in £, $ or €). It stands in contrast to the way the labyrinthine processes of our routine Equipment Programme grinds onwards to furnish our own military. There, just two drone programmes – one Army, one RAF – have taken decades, to procure tens, that cost tens of millions each. Three billion pounds is wrapped-up between them, and the drones themselves, about 60 in number, are no more survivable than those operated by Ukraine today that are expected to last a few days at the most. This is not an economically sustainable way in war.

One, the RAF’s PROTECTOR drone programme, is cited approvingly in the speech as an example of new and modern kit entering service now. Up to a point, Lord Copper. Yes, we have recognised the increasing importance of drones – but we are designing and procuring them as we would expensive, manned aircraft. We don’t appear, yet, to have institutionalised into our core the mechanisms behind the rapid evolution of cost-effective and semi-expendable drones that we will need to prosecute an actual war.

Mutatis mutandis, similar points can be made across the MOD’s Equipment Programme. When we finally get our 148 Challenger 3 tanks in 2030, we still won’t have an associated tank factory that is the necessary capacity for fighting a protracted war. (Poland is buying 980 extra tanks, the latter tranches built exclusively in their own factory being constructed in parallel.) The 1,300 armoured vehicles cited in the speech as being ‘on contract’ will be delivered some time in the future, but they are already late and over budget. When it was first given the go-ahead the Type-26 Frigate was to be an agile middle-weight declared to come in at under £200M. Currently the cost is forecast at £1.3Bn, and its heli-deck will now take a huge Chinook. There is not just a physical cost here but a serious opportunity cost too.

The extra money that has had to be found to push through these ever more bloated programmes could have been spent on ammunition supply. Little is said in the speech about this most vital of wartime capacities. Yet the reality is that Ukraine is now suffering badly because the Western nations (NATO) have not just given all they can spare but pretty much all they’ve got. NATO’s most senior officer has declared ‘the bottom of the barrel has now been reached’. The smaller nations nearest to Russia have long understood the realities, but having the smallest economies their relatively Herculean efforts have only scratched the problem’s surface. The middle powers – UK, France, Germany, – have sat on their laurels and hardly spent a pfennig on new plant. The US has belatedly invested in new factories but even it struggles – by 2028 it will be able to make shells at the rate that Ukraine consumes them now. Overall, Euro-NATO looks likely to actually deliver less than half of its promised ‘Million by March’ (2024), which would be just a third of the rounds Ukraine actually needs. Ukraine is now rationing itself and missing open goals on the battlefield as it can’t expend the ammunition; it is no surprise, therefore, that commentators ask if Putin might be winning.

That point about Euro-NATO is salient. What happens to NATO’s ability to support Ukraine if Trump wins next year’s US election? We can’t know for sure, but candidate Trump has been explicit in criticising both free-loading NATO partners and Ukraine. All we need know is that Putin’s entire strategy revolves around holding out in the hope, and increasing expectation, that Trump wins and NATO equivocates in its support for Ukraine. Nor is Trump the only possible disruptor. Erdogan and Orban are already obstructive.

So the speech’s breezy dismissal of concerns over NATO’s relative strength – describing them as “absurd” – might be a hostage to fortune in two ways. It is quite possible to imagine NATO’s traditional political solidarity being threatened as never before, and by the country that was its single-most, indispensable guarantor. And, secondly, NATO’s ability to logistically sustain a real war. While NATO’s shop window contains some exquisite kit, and on paper the number of troops look significant, an arsenal that runs out before the end of the week, and no defence industrial base to speak of to replenish it, is not a serious war-fighting polity.

In contrast even sclerotic Russia, having been allowed to grind on as we fetter and ration Ukraine, is finally learning lessons – its drone production farm is now on a par with Ukraine’s, despite nominal sanctions. (Being broken with the tacit help of many in NATO countries.) Russia has much hard-won experience in this new way of war, and she now knows how to mobilise a wartime economy and has done so. Assuming, as CDS does, that the associated economic drag on Russia’s economy will pull it down before the factors already mentioned force Ukraine to sue sounds like banking on a damn close run thing. No wonder the Poles, and recently even some Germans, have started to sound the alarm.

Whatever his personal views, CDS has to maintain the party line in public. He certainly can’t say anything that questions NATO partners’ commitment, and we trust he is working diligently and quietly behind the scenes on these matters. But in the other areas mentioned he could still have taken a glass half-full position for public consumption while suggesting that there remains more to do in demonstrating we have learned the necessary lessons from current conflicts. More on establishing ‘prototype warfare’ at speed, and less justification of legacy acquisition. More on a revived and sustainable defence-industrial base. More on standardising and simplifying warstocks and shared wartime logistics across NATO and the Joint Expeditionary Force.

Finally, it would have been pleasing to hear CDS sketch out in a little more detail how today’s security challenges represent an organised push against democracy itself. And that it has, as Ken McCallum of MI5 outlined earlier this year, both a home and away dimension. Perhaps then we will be able to sell to NATO’s electorates the complexity of the strategic landscape, and that hoping to get away with dealing only with the immediate, local concerns will not be enough ‘statecraft’ if they wish to sustain the way of life to which they have become accustomed.