The key challenge that economists have when describing an economy is distinguishing between where the economy lies in the current economic cycle from the structural or secular trends that shape its medium and long-term performance.

Above-trend growth in the mature phases of a long economic recovery

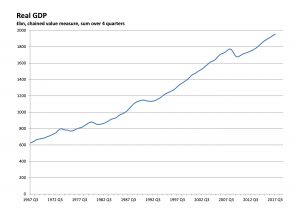

In 2018 the UK economy is likely to exhibit growth above its trend rate of economic growth and is in the mature phase of an economic expansion that started in 2009 following the Great Recession. Output is 16.5 per cent above the level of economic activity at the trough of the recession in 2009 and is now 10 per cent above the previous peak in 2007. In 2017 output increased by 1.8 per cent following growth of 1.9 per cent in 2016. The trend rate of growth that the UK economy can realistically sustain is probably somewhere between 1.5 and 1.9 per cent a year. So the UK has probably been growing at or slightly faster than its trend rate of growth over the last few years. Something reflected in the scale of its balance of payments current account deficit.

Long shadow of a banking crisis

By any normal or realistic criterion this is a solid economic performance given the constraints that the UK economy operates within as a mature advanced economy, with an aging population and following a banking crisis. The experience of economic history is clear that banking crises cast a long shadow over the economic performance of countries that experience them.

Product and labour markets that can adjust to change

One of the striking features of the last eight years has been that the UK economy has recovered relatively well from the adverse economic shock generated by the financial crisis. This resilience is in many respects even more impressive given that the UK has a large financial sector and the Great Recession exposed the fragility of the UK public finances in the first decade of the 21 century. In practice a deflationary monetary shock was amplified by the necessity of a fiscal structural adjustment that would take about half a generation to complete.

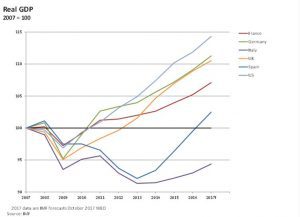

An economy that has performed relatively well in recovering from the Great Recession

The UK is among advanced economies that have exhibited the strongest recoveries. The best performing economy has been the USA, followed by Germany and the UK. The contrast with France and other members of the euro-zone such as Italy and Spain is instructive.

The UK is among advanced economies that have exhibited the strongest recoveries. The best performing economy has been the USA, followed by Germany and the UK. The contrast with France and other members of the euro-zone such as Italy and Spain is instructive.

UK economic growth will be around 1.7 per cent this year, in line with its trend rate of growth and the risks are skewed to the upside. There will continue to be a powerful external monetary stimulus arising from the lower exchange rate, the world economy is growing swiftly at over 3 per cent and there is something of a coincident international economic cycle with US, euro-zone, Japan and the emerging economies all performing strongly. Domestic inflation will fall in coming months generating positive real balance effects

Current differences in the phases of the UK and Euro-zone economic cycles

The UK and euro-zone are at different stages in their respective economic cycles following the Great Recession. The UK has enjoyed a long period of recovery and exhibited a pace of economic expansion at or slightly faster than its trend rate of growth and is now in the mature phase of a lengthy period of growth. In contrast the euro-zone, as a whole, is now enjoying a period of expansion after a lengthy period of stagnation following the Great Recession. The euro-zone will grow at around 1.7 per cent or more but this is significantly faster than estimates of its trend rate of growth that are around 1 per cent (e.g. OECD).

The significant above trend growth in the euro-zone is being driven by a powerful and internal monetary stimulus that could expose the fundamental asymmetric challenge of its monetary authority. In short what over any protracted period is appropriate for Germany, Austria and the Netherlands may not be the appropriate monetary policy for Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain and vice versa.

A strong and flexible labour market that is approaching full employment

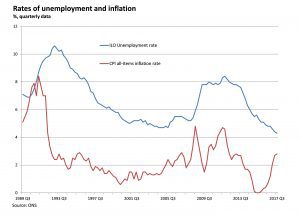

The UK economy has shown that it can perform in the way expected of an advanced mature economy. It weathered the Great recession reasonably well. It has flexible product and labour markets that adjust efficiently to changing circumstances and a labour market that has performed exceptionally well both during the period of falling output and in the subsequent recovery. Moreover the extent of its capacity to absorb change has been illustrated by the way in which a significant contraction in public sector employment has been more than offset by an expansion of private sector jobs. Unemployment has fallen and employment has expanded steadily, to such an extent it is not clear how much further employment can increase i.e. we are approaching full employment. Moreover there will be effects on employment arising from the implementation of the National Living Wage that are likely to constrain employment growth in relation to those with low levels of skills.

The UK economy has shown that it can perform in the way expected of an advanced mature economy. It weathered the Great recession reasonably well. It has flexible product and labour markets that adjust efficiently to changing circumstances and a labour market that has performed exceptionally well both during the period of falling output and in the subsequent recovery. Moreover the extent of its capacity to absorb change has been illustrated by the way in which a significant contraction in public sector employment has been more than offset by an expansion of private sector jobs. Unemployment has fallen and employment has expanded steadily, to such an extent it is not clear how much further employment can increase i.e. we are approaching full employment. Moreover there will be effects on employment arising from the implementation of the National Living Wage that are likely to constrain employment growth in relation to those with low levels of skills.

Realism about the UK’s trend rate of growth

For most of the last twenty years official judgements about the UK’s trend rate of growth have been unrealistic and too optimistic. In 2010 the March Budget Red Book was based on the assumption of a trend rate of growth of 2.75 per cent. The Great Recession both exposed the fact that the UK had a lower trend rate of growth and more structural supply performance challenges than previously thought. The consequences of the banking crisis for credit availability and the micro-economic consequences of the measures taken to stabilise the economy further reduced the potential path of growth. Today potential growth is likely to be in the range 1.5 to 1.9 per cent a year. The Office for Budget responsibility’s budget documents in November 2017 finally recognised the position and may now be slightly pessimistic about the rate of sustainable growth. The UK economy is not the only economy where estimates of the tend rate of growth have been lowered. Economists at the Congressional Budget Office and the Federal Reserve Board now estimate that the US trend rate of growth is something closer to around 2 per cent rather than 2.5 to 3 per cent.

Outlook for Prices and Consumers

In 2017, consumers’ finances were squeezed by rapidly rising prices. Inflation is likely to fall from its current 3.1 per cent towards 2 per cent through 2018 easing pressure on consumers. The rise in inflation over the last 18 months has been caused largely although not exclusively by the sharp fall in sterling after the EU referendum. As this effect falls out of the 12-monthly calculation of the price indices its rate will fall back towards 2 per cent. The pass through from the exchange rate to domestic prices was mitigated by relatively benign international commodity prices and increased competition in the retail sectors. The labour market remains buoyant, employment levels may be little changed and the price of houses will continue to rise modestly by zero n to 3 per cent.

UK Monetary Policy

We expect Bank Rate to be increased by 25bps to 0.75 per cent in 2018 as part of the MPC’s declared intention of a gradual and modest tightening. But in our view interest rates should be significantly higher, say 2.5 per cent. Our judgement is that the trend rate of growth has fallen; probably to between 1.5 and 2 per cent a year as productivity growth has slowed and the tax system has become more complex and exhibited increases instances of high marginal tax rates on highly productive workers. Given the scale of the balance of payments current account deficit and the limited spare capacity the central bank should be prepared to tighten domestic monetary policy more aggressively, particularly if any signs of incipient inflationary pressures are presented in the data.

International context to UK Monetary Conditions

The actions of all central banks will be coloured by significant changes in US monetary policy. First there is a new team. Mr Jay Powell takes over from Dr Janet Yellen in February. Unlike recent Fed chairs he is not an economist and represents a reversion to a more traditional Federal Reserve appointment where policy makers have been drawn from experienced lawyers, bankers and financial market practitioners. Mr Powell is likely to maintain Dr Yellen’s cautious approach to returning American interest rates and monetary conditions to a more normal level. Second the new team at the Fed will be continuing the complex task of unwinding the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet during a period when the US Treasury will be increasing its pace of borrowing. Third the US administration will want to make further progress on liberalising banking and security market regulation, which could have unexpected consequences for monetary conditions. These factors have the potential to either tighten monetary conditions sharply and at the same time to potentially loosen them unexpectedly. There is a tension between the potential conflicting evolution of US policy that could have wider implications for international liquidity

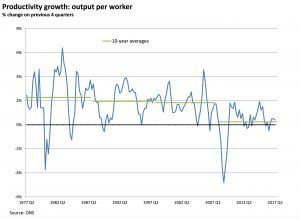

Productivity

The causes of the current weakness in productivity growth are unclear but seem unlikely to be resolved in the short term. But a modest cyclical pick up is possible in 2018: “full employment” may prompt companies to increase investment in order to boost output for an unchanged level of employment. But this cyclical improvement should not be confused with an improvement in the underlying trend.

The causes of the current weakness in productivity growth are unclear but seem unlikely to be resolved in the short term. But a modest cyclical pick up is possible in 2018: “full employment” may prompt companies to increase investment in order to boost output for an unchanged level of employment. But this cyclical improvement should not be confused with an improvement in the underlying trend.

Productivity growth in the UK has been disappointing for more than twenty years. It fell sharply after the Great Recession with that fall in output both exposing the UK’s supply constraints and resulting in direct damage principally as a result of the micro-economic consequences of very low interest rates and quantitative easing. Part of the weakness in the UK’s productivity performance has been the creation of a flexible labour market that maximises employment and a competitive jobs market where employment is used in place of capital.

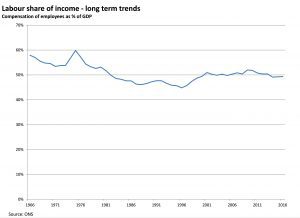

Wages and the Distribution of National income

An interesting feature of the UK economy over the last twenty years has been the way that the share of labour within national income has risen and been maintained. This is in marked contrast to other economies as the IMF illustrated in its Economic Outlook in April 2017. It is worth noting that if anything the national accounts data probably under estimates the income attributed to labour given the changes in the tax structure that have encouraged employees to incorporate with result that a significant proportion of employee ‘labour’ income is recorded as company profits. Part of the reason for the high ratio of income attributed to labour within UK national accounts arises from the high levels of employment and the success that the UK has had in creating jobs, especially for those with few skills and little in the way of training and education.

An interesting feature of the UK economy over the last twenty years has been the way that the share of labour within national income has risen and been maintained. This is in marked contrast to other economies as the IMF illustrated in its Economic Outlook in April 2017. It is worth noting that if anything the national accounts data probably under estimates the income attributed to labour given the changes in the tax structure that have encouraged employees to incorporate with result that a significant proportion of employee ‘labour’ income is recorded as company profits. Part of the reason for the high ratio of income attributed to labour within UK national accounts arises from the high levels of employment and the success that the UK has had in creating jobs, especially for those with few skills and little in the way of training and education.

The UK is a market economy that inevitably exhibits a wide dispersion of market incomes. In a modern social market economy there is a need to strike a balance between efficiency and equity. Forty years ago that balance was not properly struck and the need an efficient competitive economy that could provide the tax base to support the social services expected in a modern welfare state and to enable private consumption and living standards to increase. Indeed the British economy experienced something close to a crisis of profitability in the mid-1970s. After a sustained programme of structural economic reform that comprehensively reformed labour and product markets and better focused spending through the welfare state the UK now strikes a realistic balance between equity and efficiency.

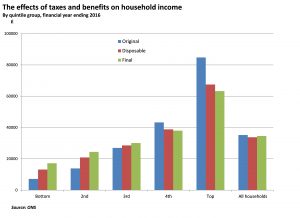

Taxes, Benefits and a Comprehensive Welfare State significantly redistribute income

In many respects this is best illustrated by the way that taxes and benefits modify market incomes. The ONS shows that in the financial year ending 2016, the average income of the richest fifth of households before taxes and benefits was £84,700 per year, 12 times greater than that of the poorest fifth (£7,200 per year). The ratio between the average income of the top and bottom fifth of households (£63,300 and £17,200 respectively) is reduced to less than 4 to 1 after accounting for benefits (both cash and in kind) and taxes (both direct and indirect). The UK has a comprehensive welfare state that is very effective at extracting tax revenue from very high income households while broadly maintaining the incentives that are necessary for a properly functioning market economy.

In many respects this is best illustrated by the way that taxes and benefits modify market incomes. The ONS shows that in the financial year ending 2016, the average income of the richest fifth of households before taxes and benefits was £84,700 per year, 12 times greater than that of the poorest fifth (£7,200 per year). The ratio between the average income of the top and bottom fifth of households (£63,300 and £17,200 respectively) is reduced to less than 4 to 1 after accounting for benefits (both cash and in kind) and taxes (both direct and indirect). The UK has a comprehensive welfare state that is very effective at extracting tax revenue from very high income households while broadly maintaining the incentives that are necessary for a properly functioning market economy.

Market economies exhibit unstable economic cycles but deliver powerful compounded growth in economic welfare over time

Market economies can be unstable and there can be protracted losses in output, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s and the recent Great Recession. Yet a market economy yields over time a steady incremental amelioration in living standards and an improvement in economic welfare that is not fully captured by changes in national income because no monetary numeraire can properly exemplify the full benefits of technical progress. Over the last ten years UK GDP has increased in real terms by 12 per cent, over the last twenty years by 49 per cent and over the last forty years by 141 per cent.

Market economies can be unstable and there can be protracted losses in output, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s and the recent Great Recession. Yet a market economy yields over time a steady incremental amelioration in living standards and an improvement in economic welfare that is not fully captured by changes in national income because no monetary numeraire can properly exemplify the full benefits of technical progress. Over the last ten years UK GDP has increased in real terms by 12 per cent, over the last twenty years by 49 per cent and over the last forty years by 141 per cent.

Looking ahead the UK faces further challenges in creating a stable monetary framework that balances the need for reliable functioning credit markets while constraining unrealistic monetary expansion. There remains a huge challenge to improve the links between schools and younger people outside the university sector with the labour market and work and training opportunities to maximise both their employability and productivity. There is huge scope for the UK’s science base and the diffusion of technology reflected in the scale and range of its new tech sectors. And the UK has made steady progress in repairing its public finances and in lowering the ratio of public spending to national income a necessary adjustment that has been needed to ensure that policy is both financially sustainable and improves the supply performance of the economy in the medium term.