Gabriel Elefteriu

Director of Strategy and Space Policy

The world was shocked this week by a barbaric and unprovoked full-scale attack on a sovereign, European and most importantly, peaceful member of the community of nations. Ukraine had already been a victim of Russia’s aggression since 2014. Now the Kremlin wants to finish the job, although its leadership might have severely underestimated the type and strength of the resistance it would meet.

No one knows how this war will end, but as the valiant Ukrainians fight for their lives and homeland against Putin’s invading forces – with Kiev itself under assault at the time of writing – the monumental implications of these events are starting to sink in.

World order

Firstly, the foundations of the post-1945 world order have been all but destroyed. The key purpose of the international system put in place both after the First and the Second World War, through the League of Nations and then the United Nations, was to avoid another major state-on-state conflict – primarily in Europe. As the Cold War showed, wars could be fought elsewhere outside Europe without systemic effects on the international security architecture. There was an additional psychological element to banishing state war from Europe, given the European heritage of the architects themselves as well as the incomparable scars left by the 1914 and 1939 conflicts.

Rightly or wrongly, then, for almost 80 years the question of war in Europe has been the benchmark for the state of international affairs. Now it has been reopened in the most brutal fashion. Cynics will point to the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo conflict as previous instances of contemporary “war” on the old continent, but neither involved a clear-cut all-out invasion of a sovereign country by another for no reason and in the face of quasi-total condemnation from the free world.

Tragically, Russia’s strike on Ukraine this week also tracks closely with the historical pattern that ended with the crumbling of the League of Nations. As with the first step on that 20th century journey – Japan’s 1931 invasion of Manchuria – it was Putin’s original invasion of Ukraine in 2014 that punctured world order below the waterline. Nothing truly significant was done in either case to repair the damage and stop the system from decaying further. Eight years later, in 1939 and 2022, after the free democracies’ failures in Ethiopia and Spain, or Syria and Afghanistan in our days, and after the exact same failure of sanctions to prevent aggression, a tyrant made his ultimate move.

Power and deterrence

In other words, deterrence seems to have failed, and when the West’s adversaries cannot be deterred anymore, it means the system has stopped working. Thanks to the existence of NATO and nuclear weapons, Putin is not likely to expand his war westwards into Europe beyond Ukraine – although Moldova remains now highly exposed, given that it has had Russian troops on its sovereign territory in the breakaway “republic” of Transnistria since the 1990s.

But the point is that whereas in the past an attack on NATO had been unthinkable first of all in political terms – in the sense of international conduct – Putin has now turned it purely into a calculation of power. By placing himself and Russia outside the civilised community of nations, effectively turning it into a rogue state and seemingly accepting any risk of sanctions, Putin has also ensured he has nothing left to lose diplomatically or politically.

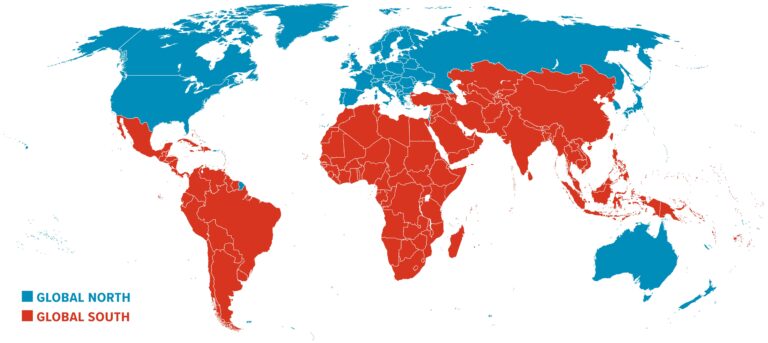

Everything is now nakedly about power – not rights, laws or rules. When Iran or North Korea do that, it is important but not foundational; when a vast, strong military state, with the second largest nuclear arsenal does it – it becomes a vital issue.

Others will take notice – especially China. There are no favourable scenarios ahead for the West in trying – as we must – to see what can be salvaged from the wreck of the “rules-based” system. One – perhaps final – test for it will be the anti-Russia sanctions regime being assembled right now. The main question is not whether the sanctions will “work” in changing Russia’s behaviour or simply crushing its economy; the sanctions rhetoric in 2014/15 is a cautionary tale in that regard. Rather, the critical issue is whether – or to what extent – the sanctions might backfire, both in terms of hurting the West, and therefore, ultimately, our defence capacity; and in terms of pushing China and Russia to finally establish a parallel economic ecosystem, as some have speculated.

The deeper question is how to restore deterrence and hold the line against the autocrats. The balance of power may not have been structurally altered – Russia will be weaker, not stronger, after this campaign – but the balance of threat and therefore the West’s strategic position has changed, requiring costly adjustments.

For example, irrespective of how the war in Ukraine ends, the allied reinforcements brought into Eastern Europe in recent weeks will have to be maintained indefinitely, and indeed significantly increased. This is happening just when China’s increasing power and aggression requires a shift of allied resources to the Pacific – with everything playing against a background of crippling self-imposed Net Zero costs, an energy crisis and in the aftermath of a pandemic.

The long game with Russia

Despite the darkening strategic picture, we should not lose sight of the problems on the other side, particularly in Putin’s corner. His regime also has vulnerabilities, which this war will bring to light – which is what wars do. The Russian Armed Forces’ performance may well fall well short of the expected mark, just as the botched Salisbury poisonings revealed a less compelling picture of GRU competence.

It is no coincidence that the UK Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, travelled to Finland in January: he will be deeply conscious of Finnish military history. In particular, he will remember how the overpowered Finns inflicted such losses on the invading Red Army in the Winter War of 1939-40 that the Soviet Union’s nominal battlefield “victory” was in fact a tactical defeat. The Finns lost territory but won a moral political victory that preserved their independence. The lesson will not be lost either on the defenders of Ukraine or on the Russian attackers.

Many ordinary Russians will be horrified to see Ukraine attacked in their name, while the Russian establishment – especially the upper elite – will face a shock in their turn when they realise that their status on the world stage is somewhere similar to that of the Taliban. The former chess grandmaster Gary Kasparov was onto something very significant in Russian psychology when he called for Russia to be expelled from all international organisations and fora, from the UNSC to the World Bank. Isolation will certainly hurt, but it is not clear whether it is possible or sufficient.

What is certainly clear already from the tragic war on Ukraine is that Russia now presents an urgent security problem with far reaching consequences, and one that requires a long-term concerted Western effort to resolve, one way or another. The world will not be the same again.

Gabriel Elefteriu FRAeS is Director of Research at Policy Exchange