At the heart of the Government’s recent Industrial Strategy Green Paper was economic productivity. While in the past, industrial policy has tended to focus on imbalances between sectors or regions, the Green Paper took on a much broader agenda of weaknesses in the supply side of the economy.

This probably explains some of the slightly tepid response the Green Paper has received in some parts of the press -—almost nobody disagrees with the overall goal of raising productivity, but there is much less agreement on which of a long list of worthwhile sounding initiatives should be the priority. The Green Paper, perhaps understandably, erred on the side of being comprehensive, rather than leaving anything out. In the future, however — given limited political and financial capital — it will be important to be more specific about what the UK’s chief barriers are. Where should we focus our attention?

There are a few different ways to answer this question.

The first is to look at the ‘productivity gap’ between the UK and its peers, and assess where we are particularly weak.

Economists are mostly agreed on the high-level factors that contribute to productivity and growth, with the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) giving as good a list as any: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication and innovation. The GCI judges the UK to be a strong performer in all these areas — in the world top 20 if not better — with the notable exception of the macroeconomic environment (85th), where high levels of Government debt and deficits drag us down. They also warn about the potential impact of Brexit on reducing trade, so the Prime Minister’s drive to turn Britain into a world champion of free trade will be essential to offset other risks. Other organisations, such as the OECD, have pointed to Britain’s poor performance with adult skills and technical education.

The second method of looking at the barriers to higher productivity is decomposing who is doing well and less well in the UK. This, to my mind, is probably the more important question — with the most significant implications relating to the ‘productivity puzzle’ that has increasingly spread across advanced economies.

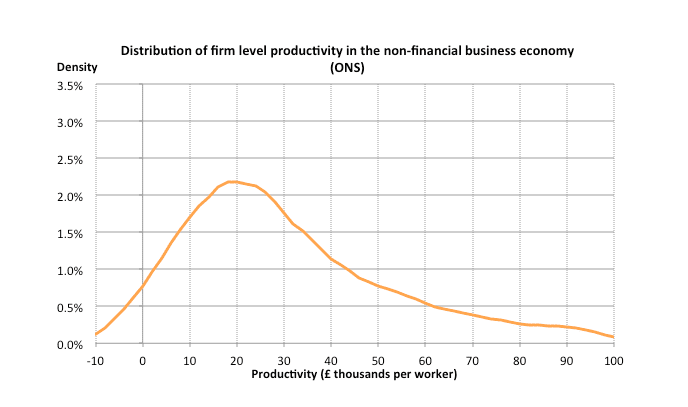

As many have stressed over the last year — including Andy Haldane, Sir Charlie Mayfield’s Productivity report, and our own Industrial Strategy paper — in many areas, our economy is world beating, but its performance is dragged down by a long tail of underperforming companies and regions. This is not just a matter of a few star sectors (ie finance and North Sea Oil), but instead a dynamic we see right across industries: a few ‘frontier’ flagship companies, and then a long tail of everyone else.

Even more interestingly, while this dynamic is particularly notable in Britain, we are far from alone, with a similar frontier and long-tail dynamic playing out across the OECD in the 2000s. In fact, labour productivity — or what you might just think of as innovation — doesn’t seem to have slowed down much if it at all in frontier firms. This is part of the answer to the puzzle that many commentators have many questioned the last few years: how can overall productivity be slowing when we continue to see rapid technological innovation in our day-to-day life, and the radical disruption of industries from cars and hotels to TV and healthcare? Innovation seems likely to be continuing as fast as ever in individual technologies or industries, but an ever larger share of the workforce is getting dragged into industries and companies which that technology hasn’t touched.

So, why is this technological diffusion not happening? Why are only a few companies seemingly able to harvest significant economic value from technological advances like the internet or the smartphone?

I can think of six plausible hypotheses:

- A broken financial system misallocated capital in the run up to the crisis, and today is acting to maintain zombie firms and preventing reallocation from low to high productivity firms.

This almost certainly explains some of the sharp productivity slowdown seen since the financial crisis. In 2014, the Bank of England estimated that it might contribute between 6 to 9 percentage points of the 16 per cent shortfall in productivity. However, the longer it goes on and the more global the productivity slowdown becomes, the more it is questioning credibility that it can be entirely explained by a broken financial system. If you look to the obvious comparator, the 1930s Great Depression, we know that despite the troubles with the financial sector in America that on some estimates this decade actually saw the most rapid growth of the twentieth century.

- Low productivity is a result of prolonged shortfalls in aggregate demand causing labour hoarding, weak investment, and a structural shift towards self-employment.

Again, this is probably partly true — and certainly was in the early years of the crisis — but the longer the productivity slowdown goes on, and the closer employment gets to what you would roughly think of as ‘full employment’, the harder this gets to put too much confidence in. Neither the UK nor the US economy look like they are particularly struggling for aggregate demand right now.

- We just need patience.

The IT-driven acceleration in productivity of the late-1990s took a lot longer finally to appear in the data than most expected, leading to a decade of ultimately futile angst by economists asking why ‘you see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics’. Given that, historically, General Purpose Technologies, like the steam engine, electricity, or personal computers, often only reach their full economic potential after at least a decade or two, we may just have to wait as new business models are invented and scaled up to take advantage of new technologies.

- Digital economy business models are dominated by increasing returns to scale and network effects, leading to increased winner-take-all effects and power law distributions.

The archetypal example of this is a Google, Amazon or Facebook. If you happen to be the winner in a particular digital market, you capture enormous economic benefits, and probably also, the tech optimists would not unreasonably argue, create significant levels of consumer surplus that traditional economic statistics struggle to measure. Once the world economy has one Google, it has much less need of a second company to do the same thing — and the Internet’s ability to near frictionlessly scale globally means that national firms don’t have the chance to embed with local competitors. In other words, Amazon has spread much faster and further than American supermarkets ever did.

Such power law dynamics match well with the distribution of overall firm productivity we see — and similar ‘superstar’ trends that have been seen in labour markets or entertainment. Another recent paper by David Autor et al finds tentative evidence of such a ‘superstar firm’ effect, with increased in a particular industry correlated with increased concentration.

How politicians should or could respond to this is much less clear.

- A lack of competitive pressure and poor management practice is reducing pressure for non-global firms to adapt best practice.

Competition is one of the most powerful tools we know for increasing productivity, responsible for at least 50-80% of overall UK productivity growth. While politicians and business growths often understandably like to focus on the friendlier topic of what individual firms can do to improve their internal productivity, the Darwinian reality is that as much and probably more productivity growth comes from bad firms leaving the market, and new firms entering. It is competition that ultimately forces firms to improve their working practices and adopt the latest technology.

This, of course, only pushes the puzzle back another step. Is there a reason to believe that the level of effective competition would have grown decisively worse over the last decade or so?

One possibility is that the West is just suffering from kind of slow traction or logjam effect, as the slow attrition of ever more regulation or planning law protects incumbents from new entrants.

Another possibility is that, as above, the kind of economic value we increasingly see in the modern economy with its inherent natural monopoly, is allowing the winners to suck in more economic rents. An intriguing report by the Council of Economic Advisors in the US last August suggested that ‘several indicators suggest that competition may be decreasing in many economic sectors, including the decades-long decline in new business formation and increases in industry-specific measures of concentration… returns may have risen for the most profitable firms’.

There is less evidence of this dynamic taking place in the UK, where some data suggests that competition has been fairly robust over the last decade. On the other hand, if the cause of lower competition is technology-induced natural monopolies, that may not necessarily be a good thing — but instead a sign that we are not building the industries of the future.

- Some other institutional, cultural, or sociological problem is standing in the way of the diffusion of best practice.

Or maybe it is something else entirely.

While some on the left would argue that the slowdown is the result of the ‘neoliberal revolution’ of the 1970s — and why productivity has slowed since then — it is hard to see the exact mechanism of how this would work.

In Britain, you could perhaps argue that too much economic activity is focused in London, which has simply run out of space — but it is hard to see how this could explain a global slowdown.

But perhaps there is another, more cultural reason for why mobility, meritocracy, and the spreading out of best practice has slowed down.

In the years to come, figuring out which of these hypotheses is really holding back diffusion is going to be really important — and arguably the key to higher productivity growth, the Government’s new Industrial Strategy, and ultimately, securing shared and inclusive growth.