Authors

Content

Foreword

Rt Hon Dame Andrea Leadsom

Former Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Industrial Strategy

Small and medium-sized businesses are the backbone of our economy. Growing up, my parents ran a small furniture business in Kent, which instilled in me strong convictions about the importance of private enterprise and the essential role Government can have in supporting it. These were convictions that I carried into Parliament, and which I championed as Business Secretary.

I’m proud of the many steps taken by Conservatives in government to make the UK the best place in the world to start and grow a business. In particular, I would highlight the Business Finance Council, which looks to make sure that SMEs have access to the capital they need to grow and thrive, and the British Business Bank that supports where commercial banks fail to do so. We have worked hard to cut red tape – which has an outsize impact on small and medium-sized companies in particular – and to enable businesses across the economy the share in the potential of new green industries. There is, however, much more to be done.

As this excellent new report from Policy Exchange makes clear, there is a key area that Government must now address, which is the urgent need to provide our highly motivated SME leaders with the skills that they need to grow their businesses. As the author recognises, the demand for upskilling is particularly acute amongst medium-sized companies – businesses with between 50 and 249 employees that may have corporate structures similar to larger firms but lack the management acumen necessary to expand and improve their operations. These companies, as the report notes, have huge growth potential, but face a unique set of challenges which often go overlooked in the conversation about government support for business.

The Help to Grow: Management Scheme is exactly the sort of programme that could have a transformative impact on these members of the business community. Early feedback and data analysis suggest that those taking part are gaining valuable skills and knowledge which they are immediately passing on to others in their companies. The only shortcoming of the scheme? We are just not rolling it out and delivering it to as many businesses as we ought to be.

So I welcome this paper and the gauntlet that it throws down to the Government. It is our small and medium sized businesses that will deliver the economic growth that this country is calling out for. Let’s equip them with the skills and expertise to do just that.

Next chapterExecutive Summary

The UK is one of the best places to start a business and to run a small business. Business set up and entry is easier here than in the United States. The UK raises a disproportionate amount of early-stage capital. Small businesses have dedicated champions in the form of the Federation of Small Businesses and the Institute of Directors. The UK conversation about small and medium-sized business is robust.

But it is a conversation far more focused on the S in the SME acronym than it is on the M. Small businesses (0-49 employees) make up an overwhelming majority of businesses in the UK and contribute an even greater proportion of businesses in the SME category.

Small businesses evoke connotations, such as a thriving high-street or businesses deeply embedded in their communities, or of a plucky tech start-up. They often function as key drivers of employment growth.1Anyadike-Danes et al. Measuring Business Growth: High-growth firms and their contribution to employment in the UK. October 2009. Link.

According to one analysis, small businesses enjoyed 60 times more mentions than mid-sized businesses in 2021-2022, and when medium-sized businesses were mentioned, 91% mentioned them with smaller firms. An analysis of Hansard over the last five years shows that small businesses were referenced four times more than medium-sized businesses.

Yet medium-sized firms – that is firms with 50-249 employees, – are a distinct and important part of the market. Medium-sized businesses provide 30% of employment and nearly 40% of total SME turnover, despite being only 2.5% (35,940 businesses as of 2022) of SME businesses. Their growth prospects are also immense. According to Beauhurst data, nearly a fifth of firms with turnover of £10-50 million and 50-249 employees had compound growth rates in either employment or turnover of more than 20% in the last two years. They are more likely to be in industries such as manufacturing, and are disproportionately concentrated in the North, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. They are much more likely to export than smaller businesses, are less likely to be family owned, and are overwhelmingly likely to have a company structure, rather than owner-manager or partnership. They also, compared to their smaller peers, spend nearly twice as much employee time each month on regulation and are much more likely to find that staff recruitment and development present their biggest challenges.2Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Business Perceptions Survey, 2020.

According to OECD data, labour productivity at medium sized firms is still more than £7,800 lower per capita than larger UK peers.3OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators, 2023. Link.

In short, medium-sized firms have distinct interests and challenges that are not reflected in the current conversation in the United Kingdom. It is essential that these businesses are supported and are able to grow and scale. They would benefit from distinct Government consideration, and from particular interventions that recognise their unique place in the market. The issue of growth and scaling up has already been addressed partly by Unleashing Capital, which pointed out significant funding gaps in terms of patient and long-term capital in the United Kingdom. That work examined the supply problem for businesses, around capital investment and business support. This paper examines key interventions on the demand-side: looking at the ways businesses access support, capital and investment, and ensuring that they deploy these things effectively.

A key part of the Government’s upskilling strategy is the Help to Grow: Management scheme. Designed for small businesses of 5-249 employees, this programme has helped businesses across the UK develop a higher growth trajectory. It is not delivered directly by Government, but through the Small Business Charter (SBC) and the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS). A key intervention, it brings together the state and the university sector to develop a strong offering for businesses. Help to Grow has strengthened peer networks, developed strong business-to-business connections and delivered vital management training for businesses of many sizes.

Indeed, data released this month shows just how impactful the Help to Grow scheme has been since its launch. Between June 2021 and February 2023, 5395 individuals participated in the scheme. In statistics released by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy for the period between October 2021 and March 2022, 91% of participants said they would recommend the programme to other business leaders. 89% said they had shared knowledge gained on the programme to others in their own business within six weeks of completion.4Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Evaluation of Help to Grow: Management, 2023.

These are encouraging results.

Uptake from mid-sized businesses has been promising too – some 14% of participants came from companies with between 50-249 employees. Yet at a maximum, the number of mid-sized businesses that participated in the programme represent just 2% of such firms. Given the growth potential of this particular cohort of businesses the Government should not limits its ambitions for the Help to Grow scheme. In this paper, we set out a number of recommendations to get even more mid-sized businesses participating in and benefiting from this programme, including:

Key recommendations include:

- Set a new target that 20% of mid-sized companies with high growth potential participate in Help to Grow by 2025. The Government should leverage HMRC data to identify precisely which companies to target when publicising the scheme and directly encourage them to apply to the programme under a targeted outreach campaign.

- Expanding Help to Grow for businesses of 50-99 employees to 3 members of management staff, and for businesses with 100 or more staff allow 5 members of staff on the programme. Better leverage data and business school expertise to design outreach for the scheme. This could include HMRC communications and leveraging business relationships with professional services firms to sell the programme.

- Create a stronger pipeline between Help to Grow and private and public programmes and initiatives such as BGF, Innovate UK EDGE, the Cranfield Business Growth Programme, and Envestors. Some businesses will want and need further support. Government data should be utilised for this purpose.

- Help to Grow should be used to trial or develop business interventions to ensure better take up and response in the future. This could include a new skills tax credit for SMEs.Work across Government to develop a clear, standard, definition for medium-sized businesses to inform policy making. Government should also create a Medium Business Champion to embed a policy voice for this group across Government.

Initial evidence shows that Help to Grow has been successful, with highly positive feedback from business. There is clear potential to expand the scheme – and the most economically impactful area to focus on is increasing participation amongst medium-sized businesses with high growth potential. Given that the Government’s own review into the programme showed that the biggest challenge to delivering the course was the recruitment of participants, a more targeted marketing and promotion campaign would be a prudent way to improve uptake.

Together, these recommendations would enhance the current Help to Grow offering, help address the specific challenges faced by medium-sized businesses, and foster a greater public policy focus on a key part of the UK’s business market. To solve the UK’s growth challenges, medium-sized businesses are a key part of the puzzle. Policy Exchange’s proposals for Help to Grow will give the ‘British Mittelstand’ the tools it needs to drive our economy forward.

Next chapterIntroduction

Medium-sized businesses are the forgotten middle of the UK private sector. Government definitions are hazy. Evidence suggests that medium-sized businesses are less productive than their European counterparts, and certainly less productive than large businesses in the United Kingdom.

Yet medium-sized businesses punch above their weight in the British economy. They account for nearly 30% of SME employment, and generate nearly 40% of SME turnover. They are disproportionately likely to be fast growing firms, and to be found in the North and Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. They are also disproportionately likely to be scaling businesses. According to Beauhurst data, 23% of businesses with 50-249 employees, with £10-£50 million in revenue, have compound annual growth rates of more than 20% either in employment growth or turnover.

This is why schemes like Help to Grow: Management are so important. Launched in 2021, the programme was designed to upskill leaders in the SME sector and support the development of their businesses. Uptake to-date in general has been encouraging. Some 5395 people participated in the scheme between June 2021 and February 2023. But participation by individuals from mid-sized businesses has been especially encouraging. Despite making up just 2.5% of SMEs, 14% of participants in the Help to Grow scheme have come from companies with between 50 and 249 employees.5Department for Business and Trade, Help To Grow: Management Course Enrolments and Participant Completions, 2023.

Table 7: Participants enrolled on the HtG:M programme, by business size. 1 June 2021 – 28 February 2023

| Business size (number of employees) | Participants enrolled (count) |

Participants enrolled (%) |

| 5-9 | 2,140 | 40% |

| 10-49 | 2,510 | 47% |

| 50-99 | 430 | 8% |

| 100-249 | 300 | 6% |

| Unknown [Note 10] | 15 | 0% |

| Total | 5,395 | 100% |

Department for Business and Trade, Help to Grow: Management Course Enrolments and Participant Completions

We can afford to be far more ambitious, however. Given the outsized role that mid-sized firms play in the economy – and the fact that more than one in five such companies have compound growth rates in employment or turnover in excess of 20% per annum – the Government should employ the Help to Grow scheme as a mechanism for providing these business leaders with the skills they need to expand and improve their companies.

This paper sets out how to achieve this, and will proceed in four parts. It first examines what a medium-sized business actually is, and identifies how the definition has become, unfortunately, incoherent. Secondly, it shows how and why small and medium-sized businesses are overlapping but distinct categories. Thirdly, it examines Help to Grow: Management and suggests ways Government’s interaction with the programme can be improved, and what steps might be taken in particular to improve the offering for medium-sized businesses. Finally, it sets out some ideas for how Government could improve the visibility and policy-making coherence for medium-sized firms.

Integral to this project has been the participation of a wide variety of stakeholders, from the private sector, civil society, and the university sector. In particular, this paper benefitted from their insight regarding Government relations with business and the implementation of the Help to Grow programme. Part of this engagement took place over two roundtables, but it also included a variety of bilateral discussions. The author would like to thank, again, all those participants for their frank discussions.

Next chapterWhat Is a Medium-Sized Business?

One of the complications of making policy for medium-sized businesses is that individual definitions can vary considerably even amongst official sources, and in the public’s mind, they can mean various things in different contexts.

One excellent example of this is the distinction between mid-sized businesses and medium-sized businesses. In the Government’s Growth Review, published in 2012. A medium-sized business is a business with turnover up to £25 million, with fewer than 250 employees and gross assets of less than £12.5 million. According to the Government, A mid-sized business is a business of turnover of more than £25-£500 million, but the Government also estimates that of these companies, more than half have fewer than 250 employees. One study by the British Business Bank found that of mid-sized businesses between £10 million and £500 million in turnover, 81% fell within the employment definition of an SME.

Yet another major study on this subject in the United Kingdom, the RSA Group’s The Mighty Middle Market, uses the term mid-sized business to refer to any business with 50-250 employees. The Government’s Help to Grow scheme, in its current iteration, specifies that the business must be small or medium-sized, but the only criteria used to determine if this category is met is an employment threshold of 5 to 249 people.

The UK Government also uses a different definition for regulatory purposes. From 3 October 2022, regulatory exemptions are now granted to businesses of up to 500 employees.

Meanwhile, Companies House provides account guidance for various company sizes. Small companies must not have annual turnover more than £10.2 million, the balance sheet must be no more than £5.1 million, and the average number of employees may be no more than 50. Medium-sized companies may not have turnover of more than £36 million, the balance sheet must be no more than £18 million, and the average number of employees may be no more than 250; this may not include a public company (regardless of size), any company carrying out insurance market activities or certain financial services activities, and any entity whose shares are traded on a regulated market.

This lack of a straightforward definition is present in the private sector itself too. Energy companies, for example, will use energy usage as one criterion by which small and medium businesses are identified.

This problem is not unique to the United Kingdom either. In fact, the definition varies between and within countries. Grant Thornton, a major accounting firm which publishes a mid-market review biannually, uses different criteria to define the term based on location. In the United States, ‘mid-market’ means firms of revenue of $100 million to $4 billion, while in Europe it refers to businesses of 50 to 500 employees.

Within countries and private sectors, there is also confusion. In one study undertaken by the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, it found that there was a wide range of definitions in use. For example, in the United States, turnover is between £15m and £800m is often used as the criterion, and a large British firm defines the sector as being between £50 and £350 million.

Even Germany, probably the greatest international exponent of the mid-sized businesses through their highly competitive Mittelstand, has difficulty in defining the term. While strictly a term denoting small and medium sized businesses, a recent study found a remarkable effect where medium and larger businesses were much more likely to identify themselves as Mittelstand than many smaller businesses who formally met the definition.

Share of self-defined Mittelstand vs objective definition

What is clear though is that the German Mittelstand has a clear definition for those who use the label and in the popular imagination. Studies suggest that, while the Mittelstand may not be a coherent category per se, it is evident that medium-sized and larger firms feel that they belong to this category, and as such understand themselves in the popular discourse and in policy terms in this way.

Compare that to the United Kingdom. In the UK medium-sized and small businesses are classed as one heading (SMEs), and this means that medium sized businesses are often subsumed into a wider discussion about a much larger group of firms. The result is a policy conversation that has failed to carve out a specific place for medium-sized businesses.

According to analysis from the RSA, small businesses enjoyed 60 times more mentions online and in the media than mid-sized businesses (607,261 vs 9,978) in 2021-2022, and of those mentions of mid-sized firms, 91% referenced medium-sized companies alongside small firms.

In parliament, there appears to be a similar dearth of references too. A quick search of Hansard keywords shows that there have been 3,001 references to medium-sized businesses since the beginning of 2018, compared to 7,151 references to large businesses and 12,245 references to small businesses. This does not appear to simply be a problem in popular culture, but in our political culture too.

This is despite the fact that while only being 2.5% – 35,940 businesses – of SME employers, medium-sized businesses provide nearly 30% of SME employment and nearly 40% of total SME employer turnover. They are a vital part of the UK economy.

SME Employers, Proportion of Total Businesses, Employment and Turnover by Size

The fact is that medium-sized businesses in the UK context are underdiscussed in the wider conversation, and lack a voice at the table. As we were collecting evidence, one participant summed up the problem nicely:

when I hear about chambers of commerce, I think the small, when I hear the CBI, I think the large” – there is relatively little institutional heft behind medium-sized businesses in the UK, and they lack both a cultural and a political presence.

For the purposes of this report, and to ensure that there is some definitional consistency, medium-sized businesses are defined as far as possible as simply businesses with 50-249 employees. Where appropriate, ‘mid-sized’ businesses refer to businesses with turnover greater than £50 million but smaller than £250 million. Some international sources, as shown above use slightly different definitions, and those clarifications are included in the text.

Of course, the socio-economic conditions that fostered the development of Germany’s renowned Mittelstand are highly specific to that national context. The UK is certainly a different case, with its own unique challenges (and indeed advantages). Nevertheless, there remains much that the UK can learn from Germany as it pertains to the prestige we accord to our medium-sized businesses, and the weight we give them in policy discussions.

Next chapterSmall and Medium Businesses – Why Make a Distinction?

It is important to make the distinction between medium and small businesses because there are definite trends that distinguish these two groups. Obviously, firms in these two categories will share many characteristics, but a micro business of 3 employees is fundamentally different from a medium-sized firm of 200. The SME definition currently encompasses both.

One of the most obvious examples of both difference and similarity between small and medium sized businesses is found in terms of ownership and organisational structure. Private businesses between 1-49 employees are much more likely to be sole proprietorships and ordinary partnerships than businesses between 50-249 people, 97% of which are structured as companies. Yet, despite differences in organisational structure, both small and medium-sized firms are overwhelmingly likely to be privately held. A British Business Bank study found that 84% of mid-sized businesses were private limited companies.

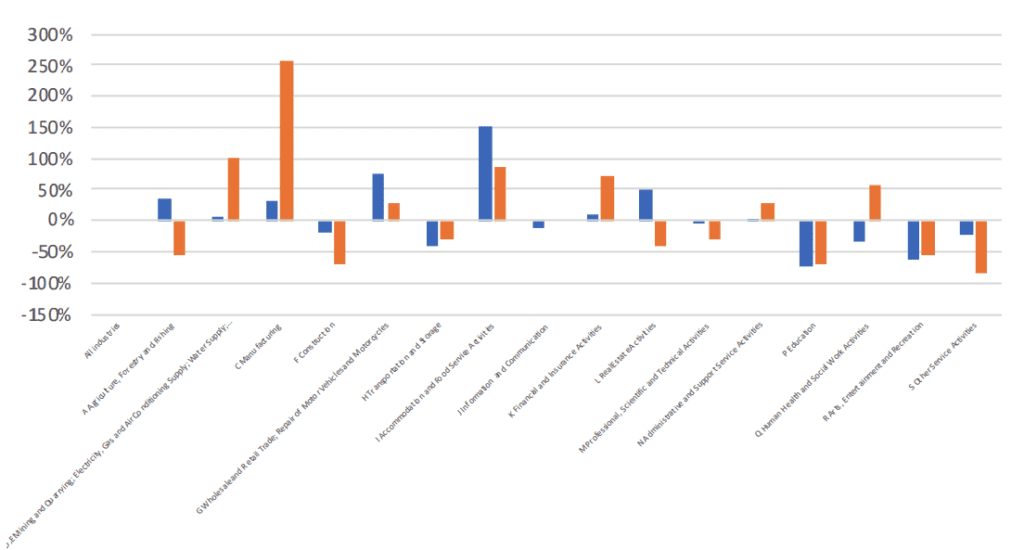

There are also dissimilarities in the industries and sectors than these different sized firms preponderate in. Medium-sized businesses are significantly overrepresented in manufacturing, mining and accommodation, while small businesses tend to be overrepresented most significantly in accommodation, wholesale and retail and to a certain extent in real estate activities.

Proportion of Firms in Each Sector Relative to Overall Proportion of Total Number of Firms

Medium-sized businesses are also faced with specific leadership and management challenges. According to the latest business perceptions survey, medium-sized businesses (42%) were far more likely to say that staff recruitment and retention was the greatest challenge to their business, compared to either the sample as a whole (16%) and micro and small businesses (21% and 30%) respectively.

Medium-sized businesses also report a significantly larger regulatory burden, with 48% of medium sized businesses indicating that they spend more than 10 days a month or more on complying with regulation, compared to 25% of businesses employing 10-49 people. Medium-sized businesses spend on average 22.4 days a month, compared to 11.6 days in small businesses.

The 250-employee threshold can also cause very particular problems for businesses operating near that frontier. According to one testimonial, when their company passed above the 250-person threshold:

We were just slightly over, and that’s an interesting dynamic, when you find yourself in that position, where you’re hitting a lot more compliance criteria.

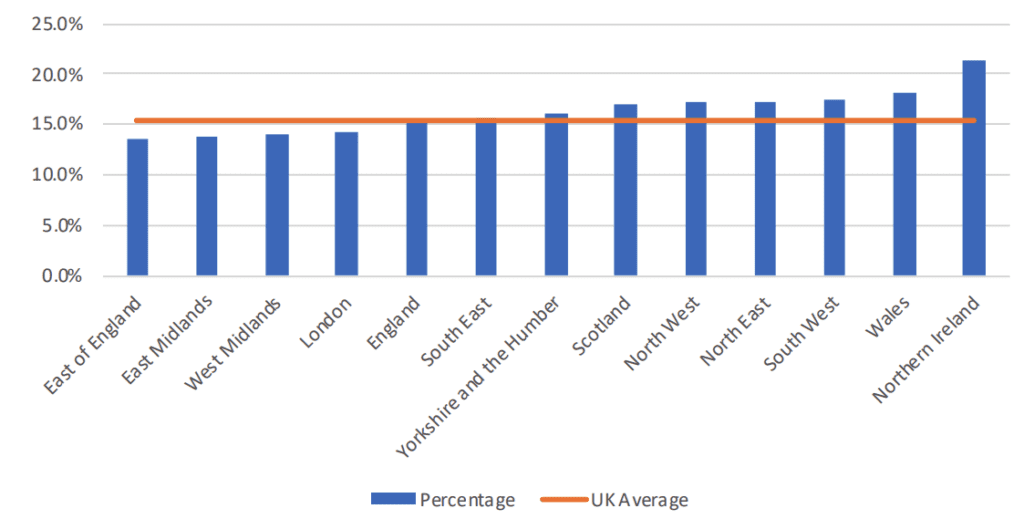

From a regional perspective, medium-sized businesses contribute disproportionately to economies in the North and Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. In fact, medium-sized businesses provide more than 20% of total employment (not including businesses with 0 employees) in Northern Ireland.

Medium-Sized Firms as a Proportion of Total Firm Employment, by Region

Medium-sized businesses face particular challenges when it comes to financing too. A UKFinance data suggests that changes in the bank rate has a greater impact on medium-sized businesses, since 75% existing loans to this group are variable rate, compared to 35% of loans to small businesses.

Indeed, ACCA reported that medium-sized companies faced the “missing middle” issue, where medium-sized businesses lacked both access to the sorts of programmes open to small and micro businesses and to equity markets to encourage growth. The result was reliance on other, more expensive forms of liquidity like bridging loans, invoice discounting and credit cards.

As one participant in our roundtables noted, it is easier to characterise micro-small businesses, which are overwhelmingly owner-manager in structure.

Medium-sized businesses are also more similar to large businesses than smaller businesses when it comes to their international exposure. Only 10.2% of businesses with fewer than 50 employees, compared to 34.9% of businesses with 50 to 249 employees, export. This is only slightly lower than the 50.2% of large firms which export. Medium-sized businesses are also much more prolific importers as well, with 41% of them importing, compared to only 9.5% of businesses with fewer than 50 employees.6ONS. Annual Business Survey Exporters and Importers. 24 August 2022. Link

“It’s easier to characterise a small business: it’s owner-manager [in structure]” – Roundtable Participant

Proportion of Businesses Exporting and Importing, By Size

Medium-sized businesses are also less likely to be family owned than other small businesses, though family businesses are still a majority of firms. According to the Institute of Family Business (IFB), 51.4% of firms are family businesses, essentially split down the middle. ONS data also suggests that family-owned businesses tend to do relatively worse on management scores than non-family firms, suggesting that medium-sized businesses may, in this respect, have similarities to smaller firms which are overwhelmingly family-owned.

However, like smaller firms, medium-sized business owners can tend to prioritise non-economic considerations as well, in ways that are reminiscent of both family businesses and of smaller businesses more generally (which tend to have owner-manager structures). In one US study, middle-market business owners tend to worry about ensuring family legacy, maintaining culture and developing an effective advisory team as they transition to a new role. Moreover, businesses of this size are dealing with new regulatory, recruitment and growth challenges, and thus business expansion in particular drives transitions. According to one study from the United States, 90% of companies that underwent a transition in the middle market experienced revenue growth in the aftermath.7Farren, Doug. Change Fuels Growth: The US Middle Market Remains As Dynamic as Ever. 15 July 2022. Link.

Considering these various traits, then, it is clear that medium-sized businesses form a distinct, but overlapping, group to the broader small business category, whose needs are not always met. There is a further challenge here too about how medium-sized businesses are able to access Government support and advice that differentiates them from smaller businesses, since they are a separate category with different needs. One example of this is support for COVID-19, where medium size businesses overwhelmingly used the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (which provided loans of up to £5 million) relative to their use of the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (which provided loans up to £50,000).8British Business Bank. Evaluation of the Bounce Back Loan Scheme, Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme, the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme. June 2022. Link.

A final point that was made to us was that at larger turnovers, businesses tend to see their growth dilemmas diverge. That is to say, a business with a larger turnover is more likely to have sector-specific challenges given the degree of differentiation and embeddedness of those businesses. This is particularly the case for businesses with turnovers above £50 million, which is one differentiation between SMEs and other businesses.9National Center for the Middle Market. Owner Transitions in the Middle Market. 2020. Link.

In fact, most of the support provided by Government is through the wider SME umbrella or directed at start-ups. Programmes like the SEIS, Start Up Loans, the Enterprise Zones, Gigabit Broadband Vouchers, Enterprise Zones, and the Small Business Commissioner are all targeted at the lower end of the SME market. The Enterprise Investment Scheme is one programme that may help the upper end of the market, but even here it is designed primarily for new businesses, and the majority of companies with greater than 50 employees were founded at least 10 years ago.10ONS. UK Business: Activity, Size and Location – 2021. 2022. Link.

One scheme that has the potential to help medium-sized businesses develop and improve is Help to Grow, a key intervention to give business leaders the skills to grow their businesses and institute better management practices. This paper focuses on Help to Grow in detail, and suggests ways that, in the framework of what is clearly a successful programme, sharpen the offer for medium-sized businesses.

Next chapterHelp to Grow Management: An Opportunity for Medium-Sized Businesses

Help to Grow was originally divided into two elements. Help to Grow: Digital and Help to Grow: Management. Help to Grow Digital provides free online support on using digital technology to enhance business performance and provide up to £5,000 vouchers to cover 50% of the cost of pre-approved software. Despite a marketing campaign, fewer than 1,000 vouchers were redeemed, or less than 1% of the 100,000 targeted businesses.11BEIS. Final opportunity for businesses to access Help to Grow: Digital scheme. 15 December 2022. Link. The digital element has stopped taking applications. One challenge raised in our discussions with various stakeholders was that this element of the scheme was highly centralised, did not use local actors, and ultimately could not generate enough interest to ensure widespread uptake.

Help to Grow: Management, by contrast, is delivered by business schools which are members of the Small Business Charter from across the UK, as an in-depth twelve-week course on leadership and management training. There are 88 Help to Grow cohorts currently being offered, delivered by over 50 institutions across the United Kingdom. Businesses may send 1 (or 2 if they employ more than 10 people) senior leaders from their business on the programme, and the course is 90% subsidised by the UK Government. The cost to businesses is £750 for participating businesses, leaving an additional £6,850 for Government per participant.

Help to Grow Management has no other eligibility criteria for participants other than they belong to a small business which has between 5 and 249 employees; these can include social enterprises, but not charities. As such, it caters to a wide variety of businesses across sectors. Its curriculum is also broad based and standardised, with 12 set modules covering, amongst others, strategy, innovation, digitalisation, marketing, finance and financial management, branding, employee and organisational management and growth planning.

Help to Grow is modelled on Goldman Sachs’ 10,000 Small Businesses initiative. Catering to businesses with between 5 and 50 employees who have a minimum of £250,000 in turnover,12Goldman Sachs. About the programme – United Kingdom. Link. 10,000 Small Businesses operates an intensive 100 hour training regimen, including residential sessions, and the programme aims to find a balance between ”formal learning, mentoring, and peer-to-peer support”.13Ibid.

10,000 Small Businesses has also had remarkable success at improving growth rates, and points to the success that Help to Grow ought to have if the programme proves successful. According to studies of businesses who have participated in 10,000 Small Businesses, 74% increase the training opportunities provided by staff, 62% launch a new product or service within a year of being in the programme, and 71% seek external financing.14ScaleUp Institute. Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses. Annual Review 2020. Link. The latest progress report found that participants increased growth by between 10% and 25% relative to what their growth would have been without the programme.15Goldman Sachs. Empowering Entrepreneurs, Acclererating Growth. November 2014. Link.

In discussing Goldman Sachs’ programme with providers, one of the key takeaways was that there was huge value in peer-to-peer learning facilitated by management programmes. In that context, one of the remarkable elements that has been replicated by Help to Grow: Management is the fact that it allows for a high degree of practice sharing across business. In our conversations with providers and with those who have been involved in the design of the course, one of the points that came across was that this participant diversity sparked a high degree of cross collaboration and peer to peer learning amongst course participants. One quote that stood out in the context of assessing Help to Grow was from an academic who provided the course:

learning with delegates from a wide range of business sectors can help people reflect on what might be taken for granted in a business or sector and then apply those lessons in ways that are relevant, and potentially innovative…”.16Small Business Charter. Grow Your Own Way: Stories from a year of Help to Grow. 2022. Link.

Data for the scheme from the period between October 2021 and March 2022 suggests that this dissemination of knowledge and expertise is taking place when participants return to their businesses; 89% report that they had shared insights with others within their company within six weeks of completing the course.17Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Evaluation of Help to Grow: Management, 2023.

Help to Grow’s aim of improving leadership and management skills is a worthwhile one in the context of the UK’s productivity problems, and the need to encourage greater growth across the economy. Evidence suggests that one of the most important measures for increasing productivity is to ensure that management is capable. One study found that strategic management practices, training and management capability in particular had a positive impact on labour productivity.18Barrett et al. Productivity of the UK’s small and medium sized enterprises: insights from the Longitudinal Small Business Survey. ERC Research Paper 67. June 2018. Link. The Chartered Management Institute has noted that poor management is responsible for 56% of SME insolvencies and are much less likely than larger businesses to offer management training.19CMI. Growing Your Small Business: The Role of Business Schools and Professional Bodies. September 2015. Link.

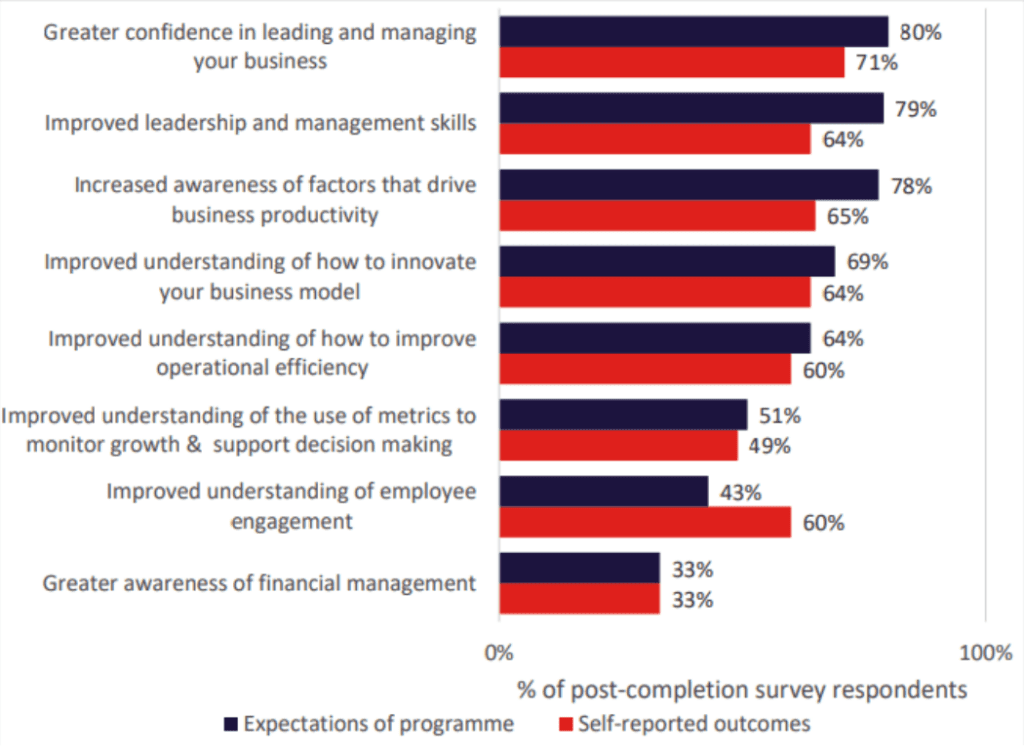

In that context, recently published data on the Help to Grow programme is very encouraging. For participants in the programme during the period between October 2021 and March 2022, over half who completed the post-completion survey form said that they had made proactive changes to their company’s operations, 71% felt more confident in leading their respective business, and 65% believed they had a greater awareness about how to boost productivity.20Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Evaluation of Help to Grow: Management, 2023.

Help to Grow Post- Completion Survey: March 2022

Individual Level Outcomes (Expectations vs Self-Reported Outcomes

The scheme could be improved further for medium-sized businesses, however. Medium-sized businesses will often be private companies and while an owner may be actively involved, there will be greater layers of management than smaller firms. For example, one of the points underlined to us by a major business school was that medium-sized businesses will tend to have many processes already in place, but may lack the organisational acumen to have mapped them properly. The businesses may be in a position where structures, IT infrastructure and payment processes are formalised, but have not undertaken steps to think about, plan or implement improvements.

Another point that was raised at the roundtables was that there were many businesses who wished to send more members of their management teams on the course, particularly those businesses with headcounts of more than 50. The view was that larger businesses would benefit from being able to send a significant cohort of their management team to Help to Grow, if applicable.

This could impose additional costs on the programme as more individuals are accepted on the course – potentially expanding the number of relevant people required to be subsidised. However, larger businesses are more likely to have the financial resources to bear some of the costs of the programme. In that context, businesses of over 50 staff should be able to send 3 people on the Help to Grow Management course, and businesses with over 100 staff should be able to send 5. This would allow medium-sized businesses to develop skills across the c-suite.

To prevent any particular business playing too large a part in any given cohort, which it has been suggested would negatively impact the peer-to-peer learning aspect of the programme, businesses should be able to send more people on the programme, but the programme should ensure no more than 2 people from any given business can be part of the same cohort.

Recommendation 1: For businesses of 50 or more employees, 3 members of management should be able to enrol in the course. For businesses of more than 100 employees, 5 members of staff should be allowed on the course, though no more than 2 on any given cohort. For additional members of management, over and above the 2 currently subsidised at 90%, the subsidy should be set at 50%, or £3,250 per participant. This additional cost should be re-invested in Help to Grow to deliver targeted marketing and outreach to medium-sized businesses.

Next chapterBetter Outreach

One current challenge faced by Help to Grow is in relation to outreach and uptake from businesses. The programme is due to run until 2025, and so improvements before then are certainly not out of the question. However, initial signs are that the programme has not been communicated as effectively as it might have been.

One survey from the Institute of Directors – a major organisation representing small and medium sized businesses – found that 62% of businesses were unaware of the programme, and that only 2% of businesses had applied. Medium-sized businesses were slightly more likely to have heard about the programme (57%) but were also more likely to say they were going to attend the programme (4%).21Institute of Directors: Results from Policy Voice Survey. February 2022. In our conversations with stakeholders, there was a strong view that a weakness of the current programme is that it has not had the requisite marketing, even as the programme itself has had positive feedback from those who have undertaken it. Data on the scheme’s performance substantiates this impression: though participating business schools had formed 200 cohorts for the Help to Grow: Management scheme by April 2022, some 122 cohorts had to be cancelled due to insufficient demand. A large part of the explanation for this is inadequacies with outreach.22Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Evaluation of Help to Grow: Management, 2023

One element that was highlighted in roundtable discussions was that the business schools, despite engaging in substantial local outreach themselves, have not been directly involved in marketing, which was handled first by BEIS and then by the Cabinet Office. This was identified by participants in our roundtable as one of the chief reasons that business schools have not necessarily seen the uptake they would wish to see in their Help to Grow programmes, even if cohorts are now sizeable. In the future, business schools should be included in the development of marketing capacity, and it should not be centralised in Government departments. Business schools know their cohorts and local areas better that almost any other stakeholder. In our conversations with providers, it was clear that there was deep commitment to local engagement, but that the campaign itself would benefit from a national, segmented campaign.

Further to this, we heard from roundtable participants that more could be done to target the programme via other avenues. One point raised was that small and medium-sized businesses tend to use accountants, banks and other high-street firms to seek professional advice. A key recommendation was that these organisations, particularly professional service firms, could be engaged more directly in advertising the programme. Some participants noted that banks, with their own support programmes, may have a conflict of interest given their private sector offerings. This is a fair point, and suggests that professional service firms may offer a more intimate and effective form of advertising for businesses. This extends beyond the firms themselves. Government should also consider whether accounting and business software businesses such as Quickbooks and Zero could be enlisted to advertise Help to Grow. These firms are used by the overwhelming majority of SMEs and therefore would be an excellent conduit for raising the profile of the programme.

Additionally, one further element that should be considered is in relation to how Government uses data and different arms of Government to reach out to business owners. The ScaleUp Institute has noted that HMRC has in particular been a useful contact for growing businesses. They found that businesses took note of HMRC communications, and in particular it prompted further action. HMRC had sent out a letter detailing potential opportunities for scaleup and suggesting they contact the Berkshire Business Growth Hub. The business in question, Insight Technologies, contacted the Growth Hub the day after receiving the letter, and within four months had secured £300,000 of investment.23ScaleUp Institute. ScaleUp Annual Review 2020.

Beyond HMRC, there are ample private sector datasets, like Beauhurst, which provide data on businesses that are growing. Government should target this group, and consider how to encourage more growing businesses to get involved with Help to Grow. Beauhurst could form the basis of a more general direct mail campaign, or the Government could leverage HMRC data to pinpoint those mid-sized firms with the greatest growth potential. Regardless, the Government ought to ensure that its outreach work campaign for Help to Grow hones in on that part of the business population where it might have the most significant economic impact.

Indeed, thinking about ways to segment the Help to Grow marketing offer is probably key to further success. Business schools are already undertaking this element in their local communities, but it was clear from points made at the roundtable that further segmentation at the national level, and a more concerted effort to target specific business segments such as scale ups or established medium-sized businesses that may be looking to start a growth trajectory, would be beneficial.

The point here is that Government databases provide some of best indications of which businesses might benefit from Help to Grow management, and Government communications for key organisations like HMRC can prompt businesses more effectively than other sources of communication to consider their options.

Recommendation 2: Government should set a new target that 20% of mid-sized companies with high growth potential participate in Help to Grow by 2025. The Government should leverage HMRC data to identify precisely which companies to target when publicising the scheme and directly encourage them to apply to the programme under a targeted outreach campaign.Recommendation 3: Government data should be used to better market and target the Help to Grow programme, and to continue Help to Grow alumni’s growth at the conclusion of the programme. HMRC should contact growing businesses to provide details of the scheme and encourage businesses with a record of growth to apply for the scheme. This has been proven to work in other contexts. Help to Grow also provides a rich mine of information on businesses, their needs, and their future plans. This data should be leveraged across Government to maintain and improve relationships.

Next chapterBetter Follow-Up

Alongside better engagement and marketing, Help to Grow would also benefit from a more concerted approach to engagement with the private sector after the programme concludes. While there are indications that some Help to Grow providers already do this, this is by no means universal.

Government has the data, via the Department for Business and Trade (DBT), HMRC, Innovate UK, the British Business Bank, and others, to connect private sector programmes at the conclusion of the Help to Grow course.

One of the challenges with any Government intervention in the private sector is to prevent against dead weight loss. In terms of Help to Grow, it is important that any scheme avoids crowding out initiatives that the private sector is already conducting.

To its credit, one of the key benefits highlighted by Help to Grow, as mentioned in the previous section, is that it attempts to capture a wide variety of businesses and encourages networking across sectors and business sizes. There are relatively few, if any, programmes that can achieve a similar cohort effect. One equivalent, as stated earlier, may be the 10,000 Small Businesses programme.

However, this strength could be leveraged further by using Help to Grow as a convening instrument for a variety of programmes. Help to Grow should operate like a pipeline to further private sector and regional interventions, like Growth Hubs, venture capital firms, the Innovate UK EDGE programme, angel investors. These initiatives are often far more specific than Help to Grow, and as such Help to Grow can play a unique role in stimulating demand for these programmes and, using the significant amount of data available from Help to Grow, to connect on to further programmes.

In our conversations, it was raised that at times Help to Grow could seem too closed off, or distant from private sector initiatives. There should be more follow-up across the programme, and more engagement with private sector initiatives that could further encourage business growth.

In particular, this route could be used to identify high-growth businesses, which, in terms of the scaleup population, are disproportionately likely to meet at least the turnover requirement to be identified as a medium sized business. The ScaleUp institute has identified scale ups as businesses with increases in turnover or headcount of more than 20% in two consecutive years or more. Of these, those that have a turnover of over £10.2 million and/or assets of £5.1 million make up 25% of the population, compared to around 2.5% of the total SME employer population. 24ScaleUp Institute. The Scaleup Index 2022. 2022. Link. These businesses are then disproportionately more likely to seek equity and other Government programmes, but may find themselves no longer of interest to Government policy, which has a tendency to focus on smaller businesses. A Help to Grow focus on building this pipeline would help address this gap.

Obviously, any pipeline would have to ensure that businesses are able to select from a set of high quality programmes. In that endeavour, there was universal agreement amongst roundtable participants that the ScaleUp Institutes list of endorsed programmes presents an ideal starting point in identifying strong private sector initiatives. The ScaleUp Institute regularly updates its list, and the latest Annual Review included 67 programmes of various kinds.25ScaleUp Institute. Find support for your business. 2022. Link.. Government should also look to industry organisations who might be able to assist and develop specific aspects of the Help to Grow pipeline, from the course to the alumni network. One way to encourage data sharing is to ensure that businesses taking part in Help to Grow are able to have their data shared with third parties. Government should ensure that GDPR permissions reflect a desire for greater follow-up.

A final point that was raised to us by industry organisations is that they played a relatively small part in the development in the delivery of Help to Grow, even though they often understand the needs of businesses and their members quite intimately. In terms of developing further management and investment pipelines once businesses complete the Help to Grow programme, there is a strong case to be made that Government should mobilise key organisations in doing so, like the Institute of Directors, the Federation of Small Business, DBT, business schools, and other key peak bodies in developing a strong post-Help to Grow offer.

Recommendation 4: Help to Grow should aim to leverage private sector programmes to deliver pipeline development and relationship management after the conclusion of the Help to Grow course. Government and Government entities like the British Business Bank, Innovate UK, the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) and private and non-profit sector organisations like the ScaleUp Institute, institute of Directors, and business school providers, should be employed to connect Help to Grow alumni with other Government and private sector growth programmes and development initiatives. Government should aim to use Help to Grow data to maintain key relationships with growing businesses over time. Organisations like the ScaleUp Institute have already provided due diligence on programmes across the UK that Help to Grow participants can access at the conclusion of the programme.

Next chapterUsing Help to Grow to Develop Government Support

Alongside improved data sharing and the use of Help to Grow as a pipeline for further private sector initiatives, Help to Grow would also offer an excellent opportunity to assess new interventions for business, and presents an excellent, data-rich cohort in which to trial new policies.

In the past, one of the most vexing elements of business policy has been the challenge of designing interventions that are both additive and receive strong take-up.. In particular, it is very difficult to get the balance right between ensuring additivity and due diligence while also widening access for SMEs. One of the most obvious examples of this challenge were Growth Vouchers. Growth Vouchers were introduced in 2014 to match fund up to £2,000 to support strategic business advice.

Evidence suggested that the programme did deliver additive benefits. Compared to the randomised group, businesses who used the programme were significantly more likely to see an increase in skills, increases in sales and increased the likelihood of looking for further advice in the future.26BIS. Growth Vouchers Programme Evaluation. Cohort 1: Impact at 6 Months. February 2016. Link. While there was some deadweight loss (1 in 6 participants would have used advice anyway), overall the programme does seem to have delivered for those businesses in the cohort.

However, the challenge was identifying the cohort to begin with. There was a view that the programme was not well enough targeted, and it was “too vague and complex” according to the Federation of Small Businesses.27Inman, Philip. Government growth voucher scheme branded a failure. The Guardian. 16 August 2015. Link. Ultimately, only 7,000 of the targeted 20,000 small businesses took part in the scheme, and the Growth Voucher programme was closed early – for take-up reasons remarkably similar to Help to Grow Digital.

Indeed, throughout our panel discussions and interviews conducted for this paper, we discerned a remarkable scepticism towards the ability of Government to communicate effectively with business, and a cynicism about business trust in Government. This extended beyond medium-sized companies and was felt across business sizes, except perhaps the very largest.

In that context, it would be highly useful for Government to be able to communicate directly to a cohort of businesses and develop strategies to communicate to the wider small and medium-sized business cohort in the future.

One particularly compelling intervention from the point of view of medium-sized businesses would be a skills tax credit, to encourage medium-sized businesses to invest in their work force. One difficulty often faced by smaller businesses is an awareness that they can at times invest in upskilling staff, only to see their staff move to a larger employer once key skills are acquired. Such firms worry, therefore, that they are not capturing the value of their training. In this context, a skills tax credit or voucher programme to encourage medium-sized businesses to invest in workforce improvement could have a significant impact. It is even more important given that investment per head in training has actually declined since 2005.28Evans, Stephen. Raising the Bar: Increasing employer investment in skills. Learning and Work Institute. May 2022. Link. The United Kingdom continues to lag other European countries in training investment, spending less than half of the European average.29HM Treasury. Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s Mais Lecture 2022. 24 February 2022. Link. The Prime Minister, when Chancellor, emphasised in particular that less than 10% of training spending goes to high quality training formal training through external providers.

This is exacerbated by the fact that the skills system in the UK is, as the LGA puts it, “a complex web of funding streams, qualification frameworks, and delivery arrangements”30LGA. Place-based adult skills training. 11 November 2022. Link.. Help to Grow: Management could assist businesses in navigating this landscape and be a rich source of qualitative data on how the skills system is interacting with SMEs. As in other areas, HtG provides an exceptional opportunity for Government to trial and connect with businesses of various shapes, sizes and interests across the country. It should be seized.

Recommendation 5: Government should introduce a skills tax credit for small and medium-sized businesses, piloted with Help to Grow alumni and participants. More broadly, HtG should be used to trial or develop such a scheme, and be used as a sounding board for the delivery of current skills frameworks and programmes.

Next chapterChanging the Broader Conversation

Alongside a far more targeted outreach and marketing campaign for the Help to Grow programme, there is also a need to sharpen the conversation around medium-sized firms in the United Kingdom. As stated previously, this category in the UK context lacks coherence in the public imagination and, perhaps as a result, lacks coherence in terms of Government policy.

The last significant intervention in this space from Government occurred in 2011, when the Government undertook studies of mid-sized businesses in the UK as part of the Government’s Growth Review.31BIS. Collection: Mid-sized businesses. 30 June 2012. Link.

Among other things, this study found that mid-sized businesses underperformed their counterparts in other jurisdictions, and tended to have lower revenue per head. In yet another sign of policy incoherence, the mid-sized business definition used by HMRC in a recent discussion about supporting this group was more than 20 employees and turnover of greater than £10 million.32HMRC. Supporting mid-sized business: maintaining and growing UK plc. 25 March 2021. Link.

Unfortunately, the Government has not used a consistent or coherent definition of this important group of companies for some time. While this may well be inevitable, in the context of a set of enterprises that share characteristics with both larger and smaller firms, it also means that Government is less capable of engaging with these businesses, and less willing to target specific interventions that may make a substantial difference. With this in mind, the Government should endeavour to develop a single definition across Government for this business group, for both policy and definitional purposes. Some key elements that should be used are:

- A consistent standard of employee headcount

- A consistent cut-off for turnover

- A consistent clarification of the difference (or lack thereof) between ‘mid-sized’ and ‘medium-sized’ business.

Alongside this honing in on the definitional term, Government could embed a cultural change by launching a review of the specific challenges facing these businesses, and identifying particular differences between this cohort and both smaller and larger businesses. It could drive this work forward by appointing a Medium Business Champion, similar to the many roles appointed to drive forward the conversation for smaller businesses.

Recommendation 6: Government should aim to align its definition of small and medium-sized businesses across departments and policy areas. The UK should appoint a Medium Business Champion to help institutionalise this change, and more broadly to imbed the interests of medium-sized businesses in policy making. Medium-sized businesses have been an unstable category in UK policy-making. This can and should be addressed by an effort across Whitehall to define this group with more clarity. Government should convene private sector partners to consider whether a medium-sized business advocacy body would assist in raising this sector’s profile.

Next chapterRecommendations

- Recommendation 1: For businesses of 50 or more employees, 3 members of management should be able to enrol in the course. For businesses of more than 100 employees, 5 members of staff should be allowed on the course. For additional members of management, over and above the 2 currently subsidised at 90%, the subsidy should be set at 50%, or £3,250 per participant. This additional cost should be re-invested in Help to Grow to deliver targeted marketing and outreach to medium-sized businesses.

- Recommendation 2: Government should set a new target that 20% of mid-sized companies with high growth potential participate in Help to Grow by 2025. The Government should leverage HMRC data to identify precisely which companies to target when publicising the scheme and directly encourage them to apply to the programme under a targeted outreach campaign.

- Recommendation 3: Help to Grow should aim to leverage private sector programmes to deliver pipeline development and relationship management after the conclusion of the Help to Grow course. Government and Government entities like the British Business Bank, Innovate UK, the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) and private and non-profit sector organisations like the ScaleUp Institute, institute of Directors, and business school providers, to connect Help to Grow alumni with other Government and private sector growth programmes and development initiatives. Government should aim to use Help to Grow data to maintain key relationships with growing businesses over time. Organisations like the ScaleUp Institute have already provided due diligence on programmes across the UK that Help to Grow participants can access at the conclusion of the programme.

- Recommendation 4: Government data should be used to better market and target the Help to Grow programme, and to continue Help to Grow alumni’s growth at the conclusion of the programme. HMRC should contact growing businesses to provide details of the scheme and encourage businesses with a record of growth to apply for the scheme. This has been proven to work in other contexts. Help to Grow also provides a rich mine of information on businesses, their needs, and their future plans. This data should be leveraged across Government to maintain and improve relationships.

- Recommendation 5: Government should introduce a skills tax credit for small and medium-sized businesses. More broadly, HTG should be used to trial or develop such a scheme, and be used as a sounding board for the delivery of current skills frameworks and programmes.

- Recommendation 6: Government should aim to align its definition of small and medium-sized businesses across departments and policy areas. The UK should appoint a Medium Business Champion to help institutionalise this change, and more broadly to embed the interests of medium-sized businesses in policy making. Medium-sized businesses have been an unstable category in UK policy-making. This can and should be addressed by an effort across Whitehall to define this group with more clarity. Government should convene private sector partners to consider whether a medium-sized business advocacy body would assist in raising this sector’s profile.