Authors

Content

Foreword

Hon Alexander Downer AC

Former Minister for Foreign Affairs and Australian High Commissioner to the UK; author of the recent Independent Review of UK Border Force.

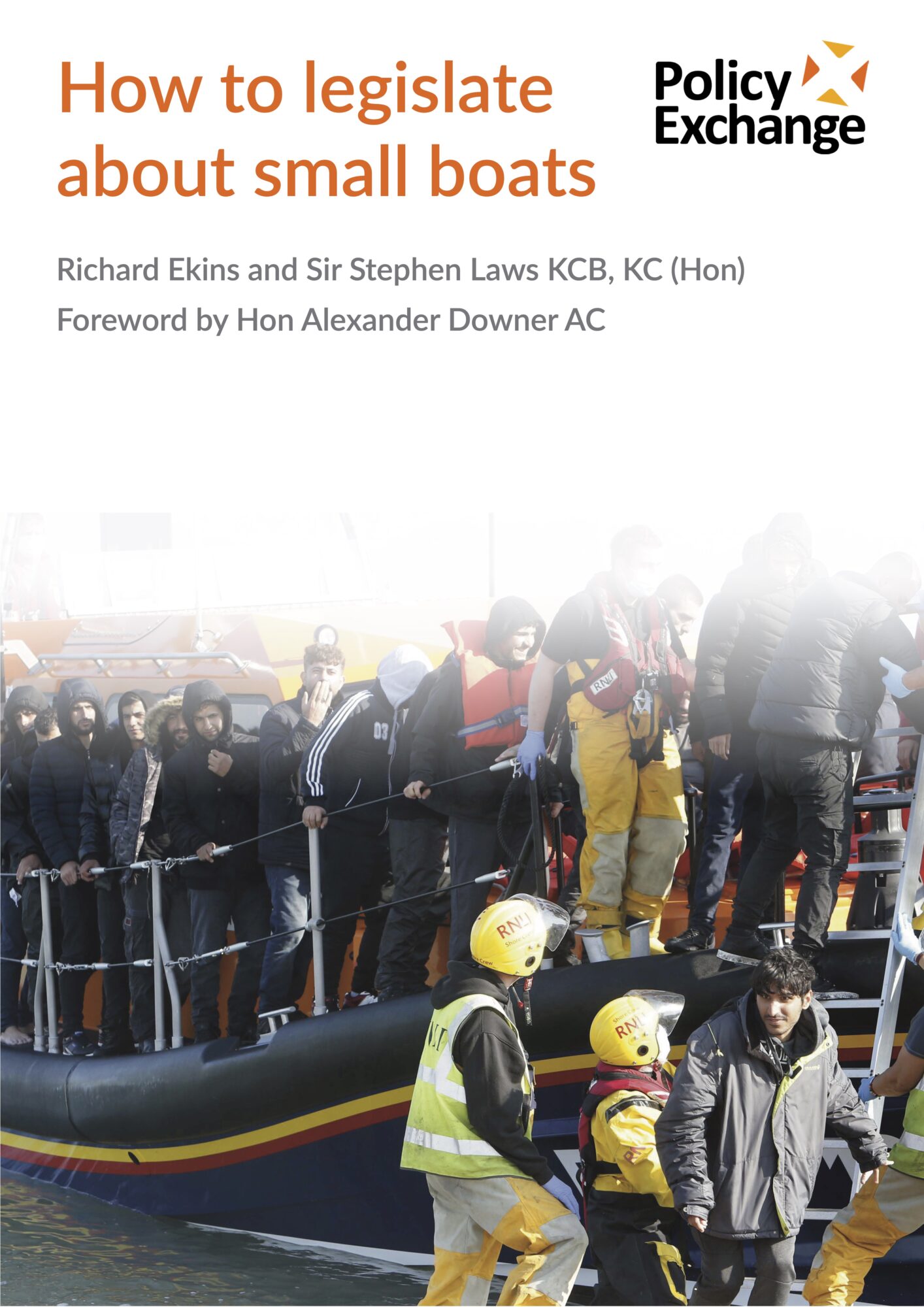

Britain’s borders are out of control. Immigration policy is now set by people smugglers rather than by the Government, as the unchecked movement of migrants across the Channel confirms.

This must change. The nation must be free to control its own borders, confident that its immigration law will be upheld, not defied. Australia faced a similar crisis and solved it – and as a one-time Foreign Minister I know that what is required is to break the people smuggling business model. But I also know, not least having carried out an independent review of Border Force last year, that successive British governments have to date found this impossible to achieve.

Policy Exchange’s new report sets out the solution to the problem. It proposes legislation that will transform the status quo, requiring the Government to take action that will make it impossible for the Channel to be a viable route for small boats to enter and remain in Britain. The report’s analysis of the failing legal framework is compelling and its outline of what must change is clear. I am proud to serve as the Chairman of Trustees of a think tank that publishes superb work of this kind — which is both intellectually authoritative and so practically minded.

What new legislation must do is to require the Home Secretary to remove from the UK any person who arrives in the UK on a small boat from a safe country, such as France. Importantly, this has to apply without exception, including to unaccompanied children, to discourage further Channel crossings and to prevent removals being challenged in the courts. Removal from the UK does not mean return to persecution and putting the people smugglers out of business does not require breach of the Refugee Convention 1951. Policy Exchange’s recommendations are tough but fair, denying settlement in the UK without compromising protection elsewhere.

But this new regime for speedy removal from the UK will not work if each and every step in its implementation is challenged in the courts. As the report makes clear, new legislation needs to specify very limited grounds on which removal might be questioned, narrowly confining the role of the courts in order to avoid derailing the policy. Relatedly, the legislation must disapply the Human Rights Act 1998 and must require removals to go ahead, regardless of what the European Court of Human Rights may say. How to change the law is a question for Parliament and it would be madness to make implementation of new legislation wait on the goodwill of human rights lawyers.

The Channel crisis is an existential crisis for government. Repeated failures to stop the crossings are eroding public trust. Bold action is needed and this report shows what must be done.

Next chapterIntroduction

In 2022, 45,756 persons crossed the Channel, entering the UK unlawfully on small boats. The previous year, 28,526 entered in this way, compared with 8,466 in 2020, 1,842 in 2019 and 299 in 2018. The direction of travel is clear. The Government is unable to secure the UK’s borders and to stop the boats. Yes, the UK is working with France to disrupt people smuggling gangs and to intercept small boats before they depart, and yes, without this French cooperation the numbers would likely be much higher. But the problem is obviously bad and getting worse.

The Prime Minister has made tackling the problem one of the five priorities of the government he leads and is reportedly set to announce new legislative proposals to address the problem. New legislation is required, because the existing legal framework is not capable of providing the basis for adequate and effective action. More specifically, the Home Secretary’s actions under the existing legal framework are at risk of being frustrated by litigation and by an apparent – and possibly related – reluctance by civil servants and Home Office contractors whole-heartedly to facilitate and implement an effective policy. Policy Exchange has been stressing these risks, and recommending Parliament act to address them, since at least November 2021. In February 2022, we were part of a Policy Exchange team that published a detailed analysis of options and a resulting plan of action, central to which was the enactment of new legislation that would mandate removals to a British Overseas Territory and then, after processing, to safe third countries.1Stopping the Small Boats: A “Plan B” (Policy Exchange, 16 February 2022)

This short paper spells out what legislation is now required. In brief, the Government should propose, and Parliament should enact, legislation that will require the Home Secretary to remove from the UK persons who have entered it unlawfully on a small boat. The legislation should mandate removal to a country where the person is not at risk of persecution, within the meaning of the Refugee Convention 1951. The legislation should also provide that no person who enters the UK unlawfully on a small boat from a safe state will ever be permitted to settle in the UK and, save in the most exceptional of circumstances, will never be permitted leave to enter the UK. The legislation should rule out domestic legal challenge against removal. Speedy and predictable removal is essential if the policy aim is to be achieved – the aim of making clear that crossing the Channel on a small boat without entry clearance is not a viable route for entering the UK with any expectation of remaining here. So, the legislation should also address the serious risk that the European Court of Human Rights will intervene in order to frustrate removals.

The Prime Minister is reportedly open to withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights if new legislation “is found to be lawful by our courts, but is still being held up in Strasbourg”, that is, if the Strasbourg Court were to “rule that the new plans are unlawful”.2Tim Shipman, “Rishi Sunak’s threat to pull UK out of the ECHR”, Sunday Times, 5 February 2023 The implication, if the reports are true, is that the Government expects its new legislation may well never be implemented and is instead preparing the ground for the political implications of what they expect to be the failure of their legislation. This would be a failure of responsible politics.

It would be a bad mistake for the Government to propose, and for Parliament to enact, legislation that, while appearing to address the problem, would in the end fail to tackle adequately the shortcomings in the existing law, and would end up stymied by litigation. Unless the Government effectively addresses the crisis in the Channel, further loss of life is likely and public trust, which has been undermined by repeated failures to honour past commitments on this matter, will continue to decline. There are, of course, practical limits to what legislation can secure, and solving the Channel crisis will require careful diplomacy and intelligent, prompt deployment of sufficient resources, as well as legal change. But the crisis will not be solved without reform to the legal framework, reform which requires legislation. This paper makes clear what new legislation must accomplish – and suggests the form it needs to take – if it is to be part of a workable solution.

Next chapterThe policy aim and the legal framework

The crisis will not end until it is clear to all concerned that choosing to cross the Channel on a small boat is not a viable means of entering and remaining in the UK. What the UK, working with other countries, needs to do is to break the people smugglers’ business model, so that no person safely in France (or any other coastal European state) will any longer be willing to engage the services of people smugglers to cross the Channel in a small boat.

Far and away the best means to this end, Plan A (as we have called it), would be a new agreement with France to accept the immediate return of persons who cross the Channel in that way. In the absence of such an agreement, Plan B (which we proposed in February 2022) should be for the immediate removal of such persons to a British Overseas Territory where their claims to asylum would be processed: some would be repatriated to their home countries, and others – those with a genuine claim to asylum – would be transferred to safe third countries. This scheme would not put any person in danger. On the contrary, the scheme would be designed to secure that no persons subject to a genuine risk of persecution were returned to their persecutors. But it would also ensure that no person who left a safe country and entered the UK unlawfully on a small boat would be able to remain, or settle, in the UK. That is the only practical means to resolve the crisis. (The proposal sometimes made for safe routes into the UK for everyone who wishes to claim asylum here can be disregarded.3See further N Biggar, R Ekins and J Finnis, From the Channel to Rwanda: Three essays on the morality of asylum (Policy Exchange, 7 December 2022) Whatever other useful contribution it would make to improving the system, it is not a serious proposal, on its own, for resolving the main problem: there is no upper limit on numbers of those who would wish to claim asylum in that way, and those who assessed their chances of success as higher using the unsafe route or whose use of the safe route was unsuccessful would still have the option of crossing the Channel.)

The Government did not take up our Plan B proposal to detain persons crossing the Channel, to remove them to a British Overseas Territory (possibly Ascension Island4Since the Plan B paper was published, the long delayed restoration of the runway at Wideawake Military Airfield on Ascension Island has been almost completed: Island Council Minutes 8 December 2022 (completion expected February/March 2023).), and to provide for British officials to process their claims there, with those with no genuine claim to asylum being repatriated and provision being made for the protection of others in safe third countries. The Government instead concluded an agreement with Rwanda, under which some persons attempting unlawfully to enter the UK could be removed to Rwanda, where their asylum claims would be processed by Rwandan officials, rather than by British officials, but with the UK, of course, helping to meet the costs for Rwanda. The Rwanda scheme involves a different means of achieving the policy aim that Plan B was also intended to realise; but it “outsources” responsibility for processing claims, rather than “offshoring” them. The Government secured the enactment of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which made some important changes to the law of immigration and asylum for implementing the Rwanda scheme; but, crucially, it did not adopt Policy Exchange’s proposal for legislation anticipating and disarming any grounds of legal challenge to removal and making removal a legal requirement, rather than merely enabling it. Nothing short of a directive by Parliament, requiring removal of unlawful Channel crossers in all but carefully specified exceptional cases, will overcome legal challenges to removal. No policy will succeed unless it guarantees that in the vast majority of cases the attempt to enter the UK by small boat will promptly and visibly end up, not in the UK, but somewhere overseas with no prospect of reaching or returning to the UK.

The Government’s attempt to remove a small number of persons to Rwanda was challenged in the High Court on various public law grounds and by reference to Convention rights. The High Court, and the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court on appeal, declined to grant interim relief blocking removal to Rwanda, partly on the grounds that if the challenge were in the end to succeed, the Home Secretary could return the claimants from Rwanda to the UK. However, the claimants also applied to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg; and on 14 June 2022, one anonymous judge of the Strasbourg Court indicated interim measures under Rule 39 of the Rules of the Court, indicating that the claimants were not to be removed from the UK until three months after the resolution of the domestic litigation, including any appeal.5For comment, see R Ekins et al, “The Strasbourg Court’s disgraceful Rwanda intervention”, Law Society Gazette, 15 June 2022 The Government did not press ahead with the flights and has shown no inclination to do so. In December 2022, the High Court ruled in the Government’s favour on the question of the Rwanda scheme’s compatibility with Convention rights, and on various public law challenges, but also ruled that the Home Secretary had failed adequately to consider the circumstances of the particular claimants.6AAA v Secretary of State for the Home Department (Rwanda) [2022] EWHC 3230 (Admin) Removal, the Court ruled, was in principle lawful but had not been demonstrated to be so in this specific set of cases; it was left open to the Home Secretary to consider each of them in more detail and to make new decisions to remove these claimants to Rwanda. The claimants have appealed and the litigation will continue.

If the Government ultimately prevails in the Supreme Court, the disappointed claimants will, inevitably, apply to the Strasbourg Court, alleging that removal to Rwanda would breach their Convention rights and requesting Rule 39 measures preventing removal until the Court considers and decides the substance of their claim. On past form, it seems likely that the Government will then consider itself obliged not to press ahead with removals to Rwanda until the European litigation has run its course, which may take some considerable time – months or years. This paper does not consider in detail the Strasbourg Court’s Rule 39 jurisprudence, save to say that the Court has invented a jurisdiction which the European Convention on Human Rights clearly does not establish. Properly understood, the UK is not under an obligation in international law to comply with “interim measures”, made by the Court under questionable authority and, as in June last year, by one anonymous judge and without hearing argument from the relevant convention state. Nor is there any obligation in UK domestic law for the Home Secretary, or a UK court, to comply with the Strasbourg Court’s interim measures. The Human Rights Act gives domestic legal effect to Convention rights but not to Article 34 of the Convention, which is the article on which the Strasbourg Court attempts to ground an obligation on member states to comply with interim measures.

The Government’s unwillingness to challenge the Strasbourg Court’s assertion of this new jurisdiction is part of the problem with the existing legal framework. Even more substantial, however, is the problem that, under the existing legislation, the Government has, at best, a liberty and authority (legal power) to remove relevant unlawful migrants from the UK, but no statutory duty to do so. The consequences of this failure to legislatively mandate removal in all but very specific exceptional circumstances are many. If or when the Strasbourg Court intervenes, the Government remains legally free, as a matter of domestic law, to stop the flights and comply with that Court’s intervention. In addition, it seems likely that civil servants and contractors (airlines) misunderstand the relationship between the Strasbourg Court and domestic law and wrongly assume that it would be unlawful for ministers or for them individually to carry out the Government’s policy of removal to Rwanda. Civil servants may also wrongly take themselves to be entitled – or, by virtue of the Civil Service Code (taken together with the Ministerial Code), to be constitutionally obliged – to defy ministerial directions that would (even if only arguably) place the UK in breach of its international legal obligations. Again, there is a good argument in international law that the UK itself is not obliged to comply with Rule 39 measures. In ratifying the European Convention on Human Rights, the UK accepted an obligation to comply with a final judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in a case to which it was a party. That is sharply different from complying with interim measures, which the Convention does not otherwise recognise. But in any case, it is not within the capacity of those responsible for producing the Civil Service Code or the Ministerial Code to turn the UK into a “monist” rather than a “dualist state”, so that the UK’s international obligations, especially those that arise from treaty, are to be treated as if they had domestic legal effect in circumstances where Parliament has not chosen to enact legislation to give them such effect. The relevant question for civil servants should be and is confined to the domestic lawfulness of government policy;7We mean the relevant question in deciding whether they are entitled to refuse to carry out the policy; civil servants should certainly alert ministers to any risk that an international tribunal may consider the policy to be incompatible with the UK’s international obligations. but nothing short of Parliamentary enactment will suffice to make it clear that that is the only relevant question.

Next chapterThe key features of any new legislation

New legislation should specify that no one without entry clearance, not even a person who is a refugee within the meaning of the Refugee Convention 1951, who has chosen to arrive or attempt to arrive unlawfully in the UK by small boat from a safe country like France will ever be granted a right to settle in the UK. This legislation would extend to maritime arrivals, including persons rescued at sea attempting to arrive in the UK unlawfully or persons intercepted making such an attempt and conveyed to shore in official vessels. (We refer throughout this paper to arrival by “small boat”, but legislation might refer more generally to maritime arrivals, perhaps — as the crisis centres on irregular entry – excluding any official ferry route. Nothing needs to turn on the definition of “small boat” and it would be unhelpful if it did.) The new Act of Parliament should specify further that the Home Secretary has a duty, under the Act, to remove from the UK every person who has arrived, or attempted to arrive, unlawfully in the UK in this way and is under a duty to refuse each such a person leave to enter the UK on that and, save in very exceptional cases, every future occasion. Legislation should make provision for detention pending required removal.

This new, legislatively specified duty to remove a person from the UK should make it clear that the Home Secretary both has authority and is legally required to remove the relevant person to a third country or territory (including a British Overseas Territory). The duty should be qualified only by (a) the person’s fitness to fly (which would be for the Home Secretary conclusively to determine, by reference to an assessment by an approved medical practitioner), and (b) a statutory prohibition on “refoulement” (return to a country in which the person is at risk of persecution within the meaning of the 1951 Convention). Even these two qualifications on automatic and universal removal would not permanently and unconditionally prevent a person’s removal, for removal would be lawful (and required) as soon as that person’s health permitted flight or their removal would not constitute refoulement.

The duty to remove should otherwise be exceptionless, although the legislation will have to make provision for a situation in which the Home Secretary would for the time being be unable to remove a person because at that time no British Overseas Territory had capacity to receive and process further asylum-seekers or because no third country was as yet willing to accept the person in question. In such a situation, the Home Secretary should remain under a continuing duty to remove the person from the UK, either repatriating him or her as soon as that can be done without refoulement or arranging for him or her to receive protection in some third country. Pursuant to this duty, the Home Secretary would be under an obligation to report to Parliament each month specifying (without names) all persons due for removal whom she has been unable to remove during the preceding month, the reason for this inability, and the steps being taken to carry out her duty.

This legislation should not apply to all persons who enter the UK unlawfully. It should apply only to persons who arrive from a safe country by small boat (in the sense explained above). It would be a mistake to enact new legislation that extended this regime of mandatory removal to any person whose entry into the UK, or continuing presence in the UK, is unlawful. There are significant differences between arrival by small boat and other types of case. Legislating to mandate removal is an intelligent response to the crisis in the Channel and is justified by the shared features of that crisis (including the risk to life the crossings involve) and the need to break the people smugglers’ business model and to do so publicly and clearly. Extending this legislation to other types of case would weaken the rationale that can be made for a strict regime. It would sweep in other cases that are not nearly so urgent or obvious and that require more painstaking, individualised attention. The prospect of such cases arising after legislation is enacted would be likely to weaken parliamentary and public support for the new legal framework and would make judicial efforts to nuance the regime more likely, and so undermine its effectiveness in relation to crossings on small boats.

The legislation should not apply to all persons who have entered the UK on a small boat since 2018. That would compound the logistical challenge that the policy already involves. It would slow the pace of removals and make the policy less likely to be effective. While no person has ever been entitled to enter the UK in this way – all such persons lack entry clearance and thus arrive and remain in the UK unlawfully – application of the new legislation back to the first crossings by small boat would have at least the appearance of unfairness and possibly retrospection. More importantly, it is also unnecessary for legislation to have this sweeping temporal application. It would be much better for the legislation to apply to those whose unlawful presence in the UK derives from a small boat crossing occurring after the announcement of the policy or some later day (depending on the practicalities of removal): perhaps the day on which the legislation is introduced into Parliament. Some element of backdating is necessary because, if the legislation were to apply only to those crossing the Channel on or after the date of royal assent, that would be very likely to encourage a “closing-down sale”, encouraging many to attempt a crossing before the new rules come into force.

Some of those who cross the Channel are children travelling with their parents. Others are unaccompanied children, which usually means teenage boys. Many persons claim to be children and some of these claims are false. There have been significant failures to make age determinations in a timely and efficient manner. The new legislation should apply to families with children and to unaccompanied children, requiring their removal from the UK to a safe third country, or to their country of origin if this can be achieved without refoulement. Legislation should specify that in carrying out her duty to remove persons who arrive unlawfully on small boats the Home Secretary may not separate family groups who arrive together.

The reason not to suspend the duty to remove in relation to families or children is to avoid undermining the legislative scheme, imposing on the Home Secretary a clear legislative mandate to remove that is not at risk of being undercut by litigation questioning the application of the scheme to persons intercepted at sea or on the beach. This is not to prioritise form over substance or, worse, administrative convenience over humanity. The UK should ensure that all persons who are intercepted and detained at the border are treated humanely and in particular that no one is returned to their persecutors. The obligation to act humanely applies to all persons but obviously has particular force in relation to children. However, the Home Secretary’s duty would be to remove persons, including children, to a safe place outside the UK, whether a British Overseas Territory (which would require facilities suitable for housing and educating children during their time there) or to a third country or territory with whom arrangements have been made to process claims and protect the vulnerable. Further, the point of extending the legislation to all who arrive by small boats, including unaccompanied children, would be to discourage unaccompanied children from making this dangerous journey and placing themselves in the hands of people smugglers. If new legislation does not apply to unaccompanied children it is entirely predictable that they and those claiming to be unaccompanied children will continue to arrive, very likely in even greater numbers.

It is clear that many of those who arrive in the UK by small boat, especially those who have made prior arrangements to work unlawfully or who have criminal connections, disappear into the UK population shortly after arrival, making their subsequent removal impossible. So, there is good reason for the Home Secretary to have a power to detain such persons pending their removal. Policy Exchange’s Plan B proposed detention pending removal to a British Overseas Territory within 48 hours of arrival in the UK or interception at sea. Longer periods of detention are clearly harder to justify, especially if they involve vulnerable persons or children, and add significantly to the cost of the policy. New legislation should authorise detention pending any removal which the Home Secretary has a duty to secure, but should not require detention in all cases, let alone detention until removal is carried out.

Where the Home Secretary is actively seeking to achieve removal, as she will be under a duty to do in all cases, and where there are grounds for believing there is a risk that the person in question may seek to abscond, continuing detention should be made clearly lawful. The strong case for legislation mandating removal, of the kind this paper proposes, does not necessitate ruling out judicial supervision of decisions about detention. Those arriving on small boats are to be swiftly removed from the UK, and detention to this end is clearly reasonable. But there may well be instances where removal from the UK is not in fact realised swiftly, and in such cases continuing detention may well be unreasonable, and legislation should not be framed to require it.

The legislation should mandate the steps that the Home Secretary must take to remove a person from the UK. It would be a mistake to leave important features of the legislation to elaboration by way of secondary legislation, which would be an immediate target of litigation. The delay in concluding such litigation would itself undermine the scheme, as would any eventual judicial conclusion that secondary legislation was ultra vires or had otherwise been made improperly. The point of mandating the scheme for removals in primary legislation is to rule out any argument that the scheme is somehow conditional and that its implementation must wait on the outcome of judicial challenge. Importantly, civil servants and especially contractors need reassurance that, in carrying out a policy that will be very controversial, they will not themselves be exposed to legal liability. The new legislation should provide that conduct in good faith to implement the legislation cannot give rise to personal or corporate liability.

Next chapterThe provision that should be made in relation to domestic legal challenge

Legislating to enable the swift removal of persons arriving in the UK on small boats requires that Parliament makes careful provision to minimise the extent to which removal may be obstructed or unduly or indefinitely delayed by litigation. If each removal is capable of being challenged, the policy will fail, even if the Home Secretary ultimately prevails in every case. It is necessary for the legislation to anticipate the likely grounds of litigation and to disarm them and the remedies to which litigation may give rise: to pre-empt all the ways in which litigation might be used unreasonably to delay or frustrate the implementation of the policy.

Legislation should specify that the Modern Slavery Act 2015 does not apply in the context of removals of persons arriving in the UK on small boats. The importance of combating modern slavery does not involve the UK being unable to secure its maritime border against unlawful entry. Removal from the UK and return to an individual’s country of origin (if this does not constitute refoulement) or to a safe third country would not constitute a failure to protect – to free – a person from modern slavery. Modern slavery legislation should not be a collateral mode of applying for de facto settlement by delaying the process of removal and perhaps taking advantage of any delay in order to abscond. Still, it is clear that across the past year claims under the modern-slavery legislation, claims meant to be made by persons otherwise living in the UK – as opposed to persons presenting themselves at the border or attempting to cross the border surreptitiously – have in fact been used to frustrate speedy removal. Legislation may reasonably specify that nothing in the Modern Slavery Act limits the Home Secretary’s duty – or her power – to remove from the UK persons who have arrived here unlawfully on small boats.

The domestic litigation that has taken place in relation to the Rwanda scheme has, predictably, deployed Convention rights that have force by way of the Human Rights Act 1998. New legislation should expressly disapply the operative provisions of the 1998 Act, specifying that section 3 (interpretation of legislation), section 4 (declaration of incompatibility), section 6 (acts of public authorities) and section 10 (power to take remedial action) have no application in relation to the new legislative scheme for removal from the UK of persons arriving unlawfully on small boats. Without legislative provision to this effect, it is inevitable that claimants will challenge the Home Secretary’s understanding of the legislation, inviting the courts either to interpret the legislation to read down her duty to remove persons from the UK (or reading in new procedural requirements) or to declare the legislation incompatible with Convention rights and thus authorising ministers to change it by executive order and ensuring that political pressure would be brought to bear to that end. If the Home Secretary were at risk of having to respond to litigation brought to secure a finding that she had acted incompatibly with Convention rights, that would fatally frustrate swift implementation of the policy Parliament had otherwise approved and put in motion.

Legislation should exclude amendment of the Act not only under section 10 of the Human Rights Act but also under any other power conferred by or under any Act. It should be for Parliament and primary legislation alone to decide whether to change the scheme and how, not for a minister to be able to initiate a change with an executive order under a power the use of which would inevitably be capable of being challenged in litigation. On the other hand, if accountability to the courts via the Human Rights Act is excluded, parliamentary accountability should (as we have suggested above) be correspondingly strengthened by legislation requiring the Home Secretary to report regularly to Parliament on the operation of the scheme in the context of Convention rights and the involvement of any relevant committee in considering the report. Any report ought also to include (though without names) a report on every case in which a person eligible to be removed under the legislation was not removed within the specified, target period for removal after their interception entering or attempting to enter the UK.

Legislation excluding the operative provisions of the Human Rights Act 1998 is not legislation that itself infringes the Convention rights as that term is defined and understood in UK law. The Home Secretary introducing such legislation could still – and should – provide a statement that the Bill is compatible with Convention rights. Some parliamentarians might argue that the Bill was incompatible with Article 13 of the Convention (which requires the UK to provide an effective remedy for breaches of Convention rights). But Article 13 is not a Convention right within the meaning of the 1998 Act. So, section 19 of the Act (which is what requires ministers to make a statement of compatibility or a statement declaring that they are unable to do so) would not require the latter sort of statement. Expressly disapplying the operative provisions of the Human Rights Act would not amount to a concession that Convention rights are to be infringed. It would be a reasonable and rational precaution to prevent the operation of the new legislation, and its policy objectives, being frustrated by litigation – litigation which the Government might legitimately expect to win in the end, but the time taken over which would effectively nevertheless defeat the policy endorsed by Parliament.

Litigation challenging implementation of the new legislation would also be likely to deploy various other traditional grounds of public law. The answer to this risk is first and foremost to draft the legislation with care, making clear that the new legislation is to form a code, and that the duties in question have been exhaustively specified. For this purpose they need expressly to limit the availability of remedial relief. Legislation should make clear, as outlined above, that removal from the UK is required (and therefore lawful) whenever a person, after the designated date, has entered the UK unlawfully on a small boat. The only qualifications on this duty should be unfitness to fly and the duty of non-refoulement, a duty which does not block removal altogether but only removal to a country or territory in which the person faces persecution. Judicial review proceedings would be available challenging the Home Secretary’s designation of a person as one who had arrived in the UK on a small boat unlawfully, if, for example, the person had been confused with another, or did in fact have entry clearance. The Home Secretary’s conclusive assessment of a person’s fitness to fly by reference to independent medical certification would in principle be open to challenge but only in the most extreme cases. Most importantly of all, perhaps, the Home Secretary’s decision to remove might be challenged as refoulement. It would be wrong for legislation to prevent challenge altogether in these circumstances. But legislation might provide that a domestic court cannot restrain removal, whether by interim relief or otherwise, unless the Home Secretary’s assessment that removal would not constitute refoulement is manifestly unfounded. Legislation might provide further that no court will have remedial jurisdiction to order the Home Secretary to return persons who have been removed to the UK, even though the Home Secretary is to continue to be required to make provision for their protection somewhere other than where they face a risk of persecution, and to be capable of being ordered to do so.

Policy Exchange’s Plan B avoided the risk of removal from the UK constituting refoulement by proposing legislation to mandate removal to a British Overseas Territory, where a person’s claims would be processed before he or she (if his or her claim to refugee status was found to be well made) would be transferred to a safe third country. The Government’s Rwanda scheme envisages speedy removal directly to Rwanda, where the person’s asylum claim will be processed by Rwandan officials. It is possible that many who arrive in the UK on small boats may allege that, if they are removed, they face a risk of persecution in Rwanda. These claims are likely to be mostly false, because few of those entering the UK in this way are from Rwanda or have any connection to the country that would expose them to danger. And in any case, the UK’s position, in line with the position taken in practice by the UNHCR, is that Rwanda is not a country that is engaged in the persecution of minorities. But it is theoretically possible that a person’s removal to Rwanda (or another country added to those to which removal is to be possible) could still constitute refoulement. The Home Secretary should of course consider that before removing the person there. A solution to the problems to which this would give rise would be to have multiple destination countries, so that a risk of persecution in one place could be answered by removal to another country, or to a British overseas territory. Legislation might make provision for such a process in relation to removal, and that would sharply discourage false claims.

It would be a mistake for legislation simply to push legal challenges to removals offshore, that is enabling persons removed to conduct and continue litigation in the UK courts (perhaps on human rights grounds, arguing that removal breaches Articles 2, 3 or 8 of the Convention), the conclusion of which might be an order of the court requiring the Home Secretary to return the person to the UK. That would generate enough meritless litigation to risk making the scheme unworkable. It has to be clear that any person who arrives unlawfully on a small boat will be removed and will not be returned to the UK. Again, legislation should prevent a court from ordering the Home Secretary to return claimants to the UK, and such orders should be prohibited even if the claim litigated from abroad has succeeded and the Home Secretary is to continue to be under a duty to take steps to protect them elsewhere, and to be subject to the jurisdiction of domestic courts in respect of that duty.

Next chapterThe likely actions of the European Court of Human Rights and their relevance

If Parliament enacts new legislation and if the Home Secretary begins the process of removing from the UK those who arrived unlawfully on small boats, claims will be made to the European Court of Human Rights. The substantive claims will allege breach of various articles in the Convention, including Articles 2, 3, 6, 8, 13 and 14. But more significant still will be the applications that are bound to be made for Rule 39 interim measures, purporting to restrain the UK from removing the applicant from the UK until the substantive claim has been heard and decided. It seems inevitable that very many Rule 39 applications will be made. Claimants have nothing to lose and everything to gain. It may be that many of these applications will be unsuccessful. However, in view of how these applications are “heard” and decided, it seems likely that many will succeed. Judges of the European Court of Human Rights will be able – anonymously and without necessarily hearing argument from the UK – to make rulings purporting to block removal of persons from the UK, with any delay to removal necessarily proving fatal to a policy and scheme that depends for its success (and its financial sustainability) on actually and visibly effecting prompt removal (and evidently permanent non-return to the UK) of almost all small-boat illegal entrants.

It might be thought by some that, if the Government prevails in the domestic litigation, the Strasbourg Court will be reluctant to block implementation of the relevant policy. Maybe. But it is more likely that the judges of the Court who hear the series of applications – possibly a great many applications – will realise that they are free, not least if acting anonymously, to scupper the Government’s plan. The Court may wish to avoid a confrontation with the UK, but then the Court will be deciding by way of a series of anonymous individual decisions and the judges will have noticed that a Rule 39 measure can bring the UK’s policy to a crashing halt. There is a risk that the Court may be tempted to exploit domestic political controversy about the policy, which should be irrelevant to its adjudicative function, by intervening to delay the implementation of the legislation calculating that that might be just as likely to produce a policy change, as an undesirable stand-off with democratic decision-makers in the UK. So, there are strong reasons to expect the Strasbourg Court to be assertive in issuing Rule 39 measures. Or to put the point at its lowest, it would be rash to make implementation of the policy that Parliament has approved dependent on an assumption of forbearance from the Strasbourg Court.

Some will argue that the Government had no option save to comply with the June 2022 Rule 39 measure and would have no option in the future if or when another such measure was indicated. Relatedly, Parliament cannot legislate in a way that prevents a repeat of such action on the Strasbourg Court’s part. Parliament is sovereign in domestic law but not in international law. What this means is that, in framing new legislation and thinking about its policy, the Government must expect Rule 39 measures to be initiated, purporting to restrain removal. If the Home Secretary is free to decide whether to remove those who arrive on small boats, then it is likely that she will not carry out removals or that civil servants and contractors will not cooperate with implementing them. But if, as we argue, legislation mandates removals, the default shifts and the Home Secretary, and civil servants and contractors, must secure the discharge of that legal duty in UK law, regardless of any contrary interim measures. This is part of the reason why new legislation is required, to mandate removal and to avoid the policy being sabotaged by judicial intervention. Writing in February 2022, Policy Exchange foresaw that litigation would attack each and every step of Plan B or any equivalent. We did not foresee – no one did – that the Strasbourg Court would intervene, in the middle of the domestic litigation no less. That said, the course of action we recommended, enacting legislation that mandated removal, would have required the Home Secretary to press ahead regardless of any eleventh-hour intervention by the Strasbourg court.

The new legislation this paper proposes would place the Home Secretary under a duty to remove those who arrive on small boats and would limit the risk that domestic courts would obstruct removals. Rule 39 measures should have no effect in domestic law and should not relieve the Home Secretary of her duty to remove those to whom the legislation applies. However, there is a real risk that domestic courts may wrongly take a Rule 39 measure to require them to provide interim relief restraining removal, or that civil servants and contractors may wrongly understand removal to be contrary to international law and for that to entitle or require them to refuse to implement the Home Secretary’s decisions in relation to removal. Clause 24 of the Bill of Rights Bill is relevant here, because it provides that in determining the rights and obligations under domestic law no account is to be taken of the Strasbourg Court’s interim measures. However, it is unclear whether, or in what final form, this provision will be enacted or whether it will be enacted in time for the commencement of the legislation that is being proposed. The new legislation we propose should expressly state that removal should proceed regardless of any rule to the contrary (save as specified in this legislation) and in particular should proceed regardless of a Rule 39 measure or any judgment or other decision of the Strasbourg Court.

For the reasons given above, new legislation should disapply the Human Rights Act and in that way should not be exposed to human rights litigation in the domestic courts, litigation that may either delay removals or may distort the legislation and frustrate its intended operation. The lawfulness of the Government’s policy should be settled authoritatively by a new Act of Parliament that mandates removal. The Government should not proceed on the premise that lawfulness would somehow remain to be determined at a later date by British courts or the European Court of Human Rights. If the Government chooses to propose legislation that does not disapply the Human Rights Act (and, in particular, does not also mandate removal notwithstanding a Rule 39 measure), then it is choosing to make its policy (even when ratified by Parliament), and its practical effectiveness, contingent on the views of British and European courts and their approval of its implementation over time on a case by case basis. Rather than raising the prospect of withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights if the courts conclude that the legislation is incompatible with Convention rights, it would be much better for the Government just to take responsibility for its policy in all its detail and to invite Parliament to mandate its implementation, and in that way to guarantee that the only way of changing what it does and how it works would be further primary legislation.

Next chapterChecklist for new legislation

In order to provide an effective response to the Channel crisis any new legislation will need to do the following.

- Impose a duty on the Home Secretary to remove persons from the UK if they are unlawfully in the UK following an arrival or attempted arrival by small boat from a safe country.

- Provide that no such person may ever be granted a right to settle in the UK.

- Provide for the Home Secretary’s duty to remove persons from the UK under the legislation to be qualified by reference only to the need (where the matter is in question) of a certificate of fitness to fly and to a prohibition on refoulment.

- Apply to all such persons (including unaccompanied children) only where their arrival or attempted arrival by small boat from a safe country was on or after a specified date before the passage of the legislation (possibly the date on which the legislation is presented to the House of Commons).

- Provide that in removing persons from the UK, family groups who arrived in the UK together should not be separated.

- Empower detention pending removal where there is a risk that persons will abscond, but not require detention in all cases.

- Provide that conduct in good faith to implement the legislation (by officials and contractors) cannot give rise to personal or corporate liability.

- Provide that modern slavery legislation cannot prevent the removal from the UK of a person to whom the new legislation applies.

- Disapply the operative provisions of the Human Rights Act in relation to the new legislation and provide that the legislation may not be amended by any power under that or any other Act.

- Confine the availability of judicial review for challenging the Home Secretary’s decision on a removal to cases where her decision is manifestly unfounded as to the identity of the claimant, as to the unlawfulness of their presence in the UK or their means and date of arrival, as to any assessment of fitness to fly or as to whether removal to the chosen destination would constitute refoulement.

- Provide that no court may order the Home Secretary to secure that a person removed under the legislation is returned to the UK, while ensuring that the court is able to require the Home Secretary to take other steps to discharge her duty to protect that person outside the UK.

- Provide expressly that removal should proceed notwithstanding any obligation arising otherwise than by virtue of requirements imposed by the new legislation itself and, in particular, should proceed regardless of any Rule 39 “interim measure” or any judgment or other decision of the Strasbourg Court.