Air Marshal Edward Stringer (Ret’d) CB CBE

Senior Fellow

Emmanuel Macron’s recent comment that France would not, if Russia uses nuclear weapons, retaliate with its own has caused a diplomatic kerfuffle in the Atlantic Alliance. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has claimed Macron “revealed his hand”, thereby weakening the ambiguity that Western strategists have employed to counter Putin’s nuclear threats. Yet they follow the equally significant comment President Biden made on 6 October at a Democratic fundraiser, that there is a chance of “nuclear armageddon” unless the Ukraine War is resolved. A bold statement by Josep Borrell of the EU that Russia’s armed forces face annihilation by Western forces in the case of nuclear use raised eyebrows as it appears to go beyond the EU’s capacities or remit.

Meanwhile, Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg refused to specify NATO responses to Russian nuclear use. Former President Francois Hollande, on FranceInfo Radio, argued that deterrence credibility requires ambiguity. Western leaders, he argued must “say as little as possible and be prepared to do as much as possible”.

Biden, Macron and Borrell’s comments demonstrate growing nuclear unease within NATO. Statements like these could play into Russia’s hands. A dispassionate, rational look at Russia’s military position, and its use of nuclear threats within its typical diplomatic approach, demonstrate the need for sober, coordinated and resolute statesmanship in response.

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who spoke at Policy Exchange in June when accepting the Grotius Prize, has warned of Russia’s standard, three-pronged negotiating tactic: submit a maximalist demand where you have no justifiable claim; maintain threats and ultimatums throughout; and do not give an inch in negotiation. As Gromyko admitted, this tactic is predicated on the revealed preference of western diplomats to seek off-ramps, and politicians to appease scared electorates. Usually, the west will compromise first, and Russia will get a significant percentage of an outrageous demand.

This is not, however, crude brinksmanship. Central to Russian strategy is Reflexive Control, a sophisticated theory of psychological manipulation within a long Soviet/Russian tradition of ‘Active Measures’. Reflexive Control plays to the fear, greed and self-regard of the target, tailoring threats, offers and blandishments to an adversary’s psychological-emotional-intellectual pressure points. Fear of nukes, greed for cheap gas, and an accompanying plausible, and clever rationale that seduces Western polities to reflexively go along with its own atavistic, instinctive leanings. And all the better if some credible Western voices can parrot the Kremlin’s lines.

Russia must employ Reflexive Control to win informationally because it is losing on the battlefield. Putin’s war has gone badly wrong. Diagnoses of strategic stalemate, so popular in the summer, have fallen flat. Ukraine’s Kharkiv and Kherson offensives retook thousands of square-miles from Russia, retaking Kherson itself is now a probability. Ukraine has severely damaged the Kerch Bridge, at once the crucial logistical link for Russian forces in southern Ukraine and a symbol of Putin’s imperial power. Mobilisation will not help: all the evidence indicates that Russia’s new soldiers are poorly trained and equipped, have low morale, and in many cases have little stomach to fight the committed Ukrainians. Putin is losing the war on the ground.

Years of informational preparation undergird Putin’s nuclear threats. The Russian military integrates nuclear use into its major exercises – indeed, three separate nuclear related events accompanied February’s invasion to remind the West of Russia’s nuclear menace and to keep out of it. Ever since, Russian military theorists and Western defence analysts have emphasised Moscow’s willingness to use low-yield ‘battlefied’ nuclear weapons in a range of circumstances. “Escalate-to-deescalate” has entered the popular lexicon.

Russia’s recent bombardment of Ukrainian cities is aimed at two audiences: Ukraine’s population, and its Western backers. A reminder of the nuclear menace comes with the choice of missiles – they could carry atomic warheads. The aim is to spread fear, fear of a terrorised population that it cannot escape endless Russian bombardment, and fear in the West that Russia remains the superpower of its nightmares that has reserves we shouldn’t provoke. In both cases the psychological effect desired is to reflexively persuade both towards seeking a negotiated settlement whereby Ukraine’s gives up voluntarily what Russia’s army cannot win on the battlefield.

Speculation over Putin’s reportedly unstable domestic position further adds to uncertainty and fear. The Russian dictator has reshuffled his military’s command structure… Evgeny Prigozhin and Ramzan Kadyrov seem to be competing openly… This image of irrationality and instability cultivates fear in the West. As the oft repeated tale taken from Putins own memoirs states – a cornered rat will do anything to survive.

And to help us get to this conclusion, petrochemical supplies are weaponised in several ways (MBS reducing OPEC production quotas) in support to provide a greed related supporting argument: after all, wouldn’t it be better for all to get back to a normalised trading relationship, and so cheaper energy.

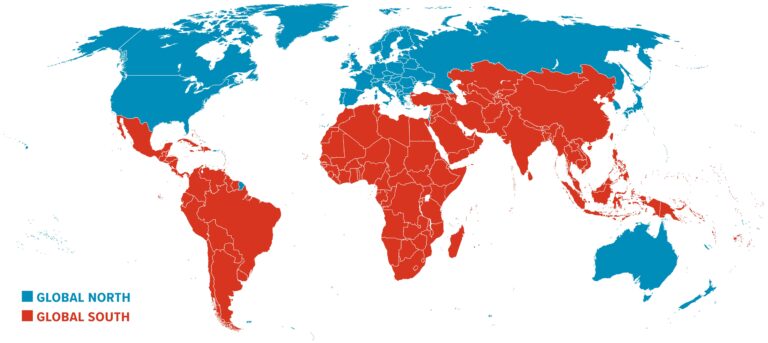

But what is really behind all this theorising on intent? As Kevin Rudd opined today: China, Russia’s closest international partner, would be horrified at the prospect of Russian nuclear use. It would trigger Taiwanese, Japanese, South Korean, and possibly Australian nuclear programmes that would severely complicate its Indo-Pacific ambitions. Following similar logic, India, an avowed nuclear power, would be horrified too. Modi was openly critical of Putin’s war in Samarkand. The West, even without employing nuclear weapons, could dismantle the Russian military machine in Ukraine in days – though that could lead to nuclear escalation. All logic speaks to Russia not using nuclear weapons.

So Macron, Biden and Borrell’s thinking is not wrong per se. But they appear to have spoken those thoughts without clearing lines with allies, thereby maintaining a united and carefully thought through position. This confusion only adds to fear and could be exploited as described. The nuclear question is live, and the stakes are undeniably high. Avoiding it or pretending it is irrelevant is irresponsible and foolish. Yet in the decades since the Cold War, Western leaders have lost sight of the discipline and care needed to manage a nuclear confrontation. We confront now a desperate adversary that preys on fear and uncertainty and seeks to promote division in the West. The statesman’s task is to put fear aside, speak with care, and act collectively with determination and prudence.