All the hard decisions announced in next week’s Spending Review are theoretically in the service of a greater aim: finally balancing the budget in 2019-20, for the first time in 19 years.

Over the past few months, the Government’s new fiscal target has received plenty of criticism. It is argued that it is too strict, reducing debt faster than necessary, and leading to unnecessary cuts to public services and insufficient levels of public investment. Many say it ties the Government’s hands too much, and will stop the Chancellor responding in the event of a recession. Conversely, others argue all fiscal rules are legislative gimmicks, inevitably abandoned as soon as the economy runs into trouble.

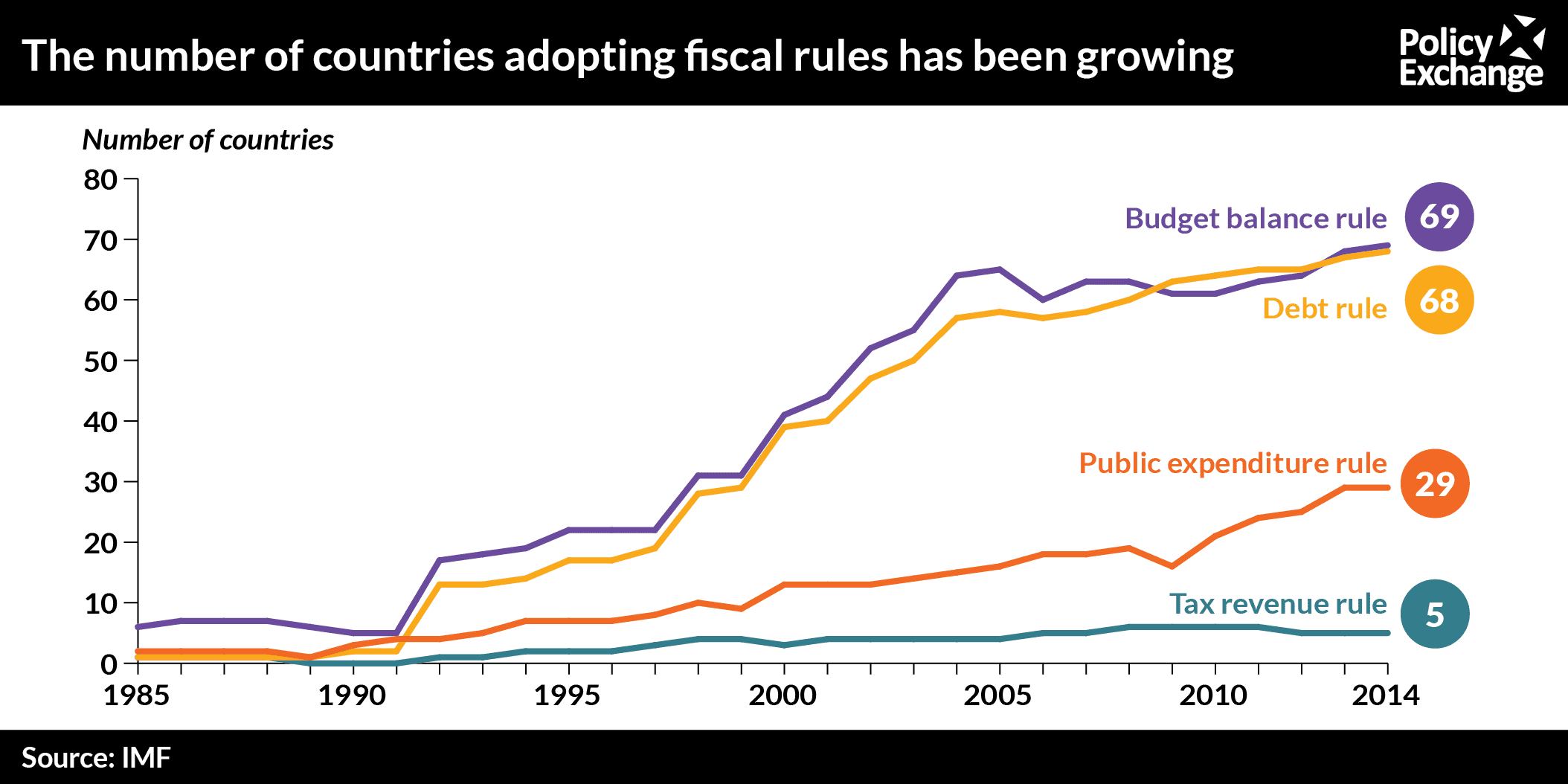

No fiscal rule is perfect. There are inevitable trade-offs to be made between preserving flexibility and credibility, theoretical optimality and how easy the rule is to measure. Nevertheless, there is a reason that over the last thirty years an increased number of countries have chosen to adopt their own rules rather than leave decisions completely to the day to day discretion of the current Government. As you would expect, stricter fiscal rules are associated with smaller deficits. While rarely perfectly adhered to, they set a framework for the Government’s long term goals, and help embed a culture of fiscal discipline.

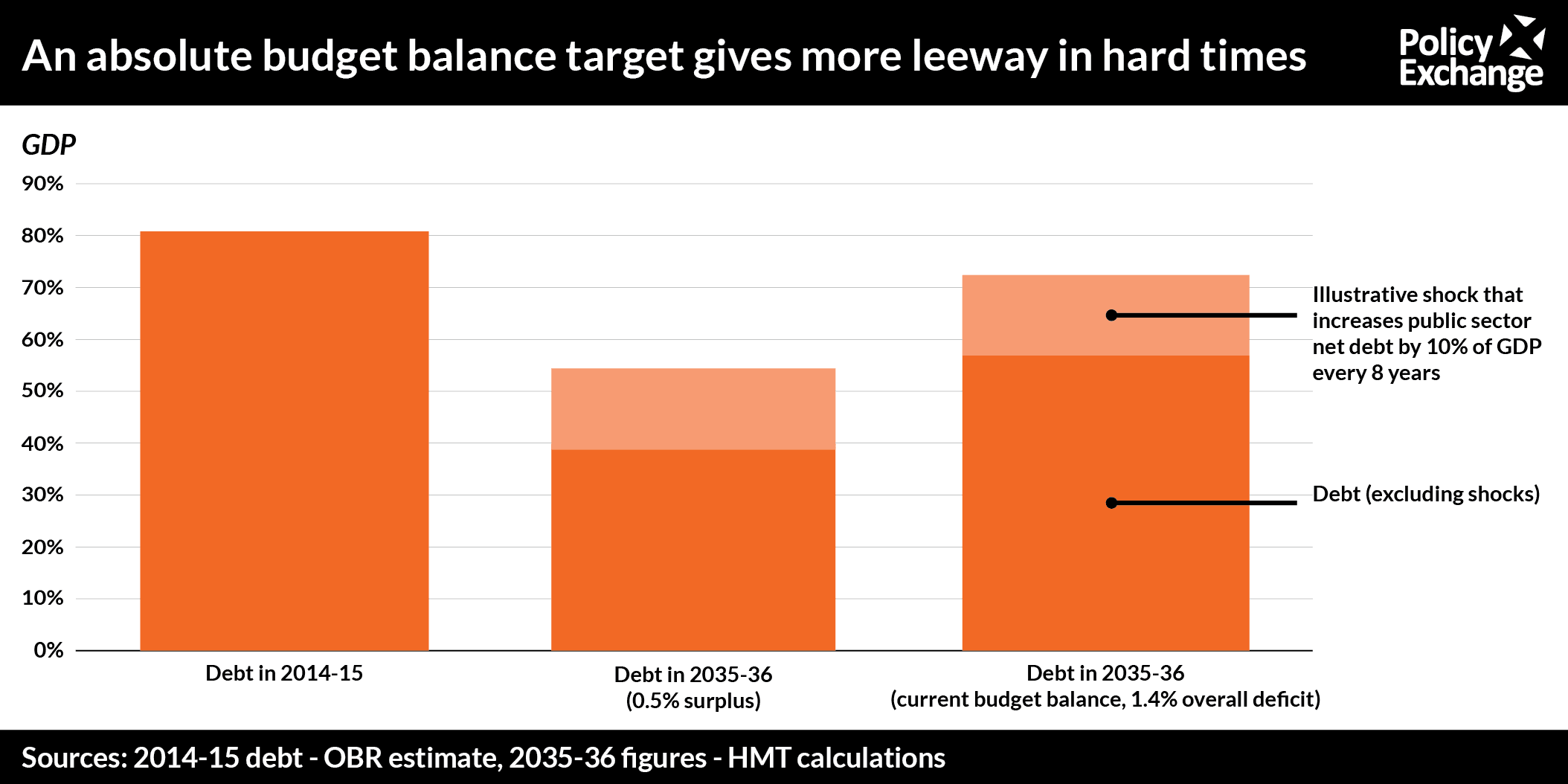

Once you have accepted the case for some of fiscal rule, the next question is what you should target. Under both New Labour and the Coalition, the Government’s theoretical target was some form of current balance, while still allowing borrowing for investment. The Conservatives have now chosen to go further than this, insisting that tax revenues should be equal to or greater than public spending full stop. Given where we are, this is not unreasonable. Post financial crisis, public sector net debt is now substantially higher at 80% of GDP, and already at the level where some studies have found an impact on growth. In a perfect world, a country can keep running a modest deficit, and still see its debt shrink as a proportion of the economy. If however, recessions continue to happen and the economy occasionally runs into shocks that increase debt, seeking to balance only the current budget can see debt fall only very slowly if at all – especially in our new world of low inflation.

Equally, given that government adherence and forecasts are inevitably imperfect, an absolute budget balance target gives much more room for error for when things go wrong. Projections of the deficit five years ahead of time were over optimistic on average by 2% of GDP between November 1998 and April 2003.

Protecting and providing enough investment is important, but you don’t necessarily have to do this through the Government’s main fiscal target. A simpler measure would be to just ringfence investment as a share of the economy, while our planning laws are a bigger barrier to investment in our economy as a whole than low government spending. Neither is protecting investment the same as ensuring generational fairness, as some sometimes imply. Making sure that we aren’t just pushing costs back a few decades, or running down our assets, is obviously worthwhile, but this is better viewed through the more comprehensive lens of a set of generational accounts, or even just the OBR’s Fiscal Sustainability Report.

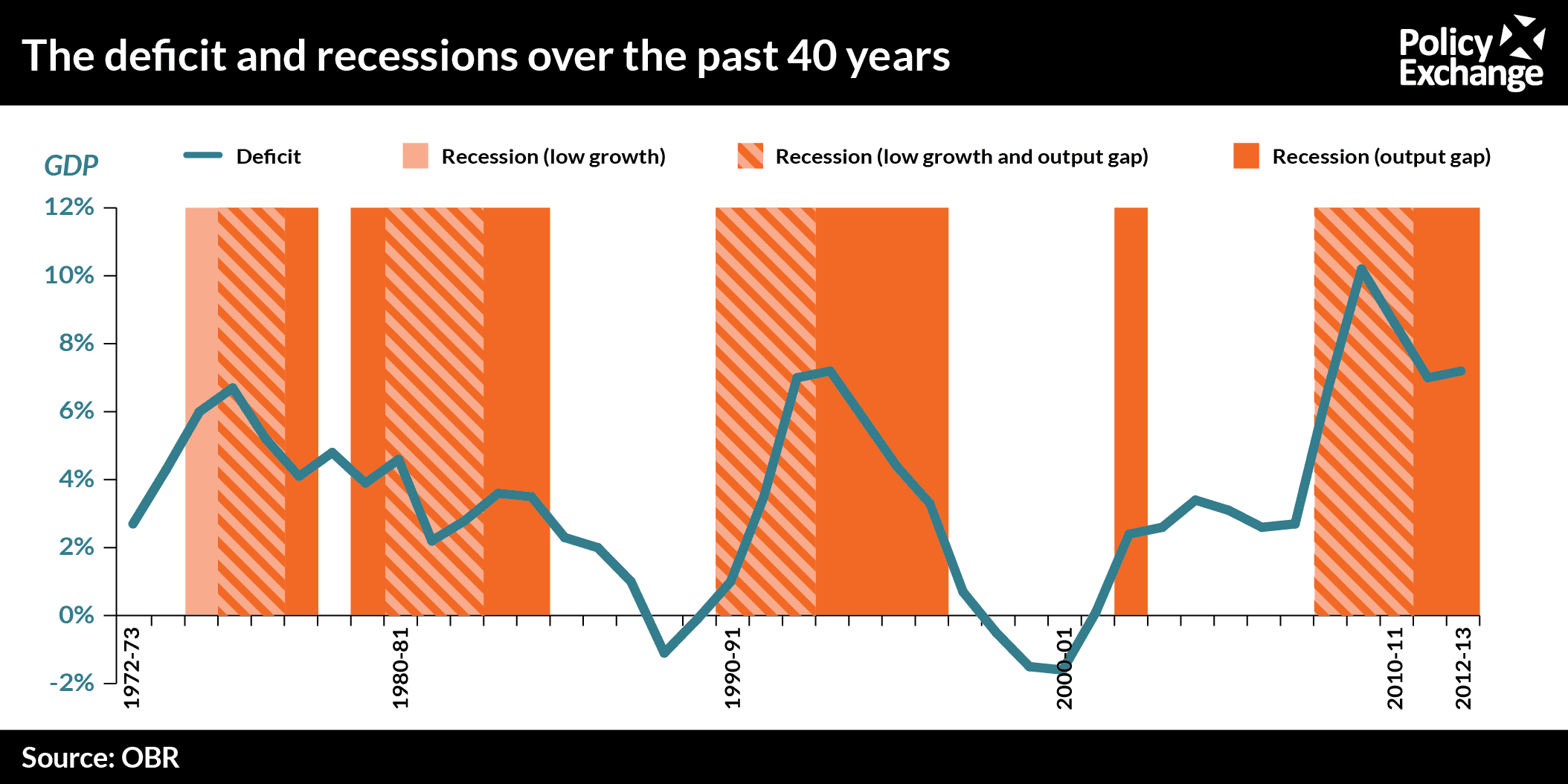

Once you know your average target, how much flexibility should you leave to respond to the ups and downs of the business cycle? In the past, Policy Exchange has argued for that it would be better to aim to target the structural deficit adjusting the target up and down for the level of spare capacity in the economy. Many people, however, have argued against structural targets, believing that trying to work out any sort of output gap is inevitably guesswork – and there is an obvious advantage in simplicity and transparency in just targeting the deficit itself. More to the point, the Chancellor’s rule includes a knockout clause where the target simply doesn’t apply if growth is forecast to dip below 1% at some point in the next five years. In practice, this would have given the Chancellor complete freedom to respond to the four major recessions of the past thirty years – or for that matter, the slowdown caused by the Euro crisis in 2011. The situation in which the rule is most likely to struggle is one in which growth is sluggish, but not low enough to trigger the exemption clause. This is a relatively rare occurrence, however: in the postwar period where growth has stayed higher than 1%, but lower than average for more than two years in a row.

In short, the rule does a reasonable job of doing what the Chancellor has always said is his goal – ensuring a fast paying down of debt during the good times.

Its biggest weakness is that it gives no guidance about what to do when we are not enjoying good times. While there is argument for leaving some discretion to treat each recession as its own special case – in practice, past experience suggests a Chancellor will stick to his judgement whatever the rules say – the danger is that this could leave the current fiscal framework completely redundant half the time or more.

The best way to compensate this would be to supplement the short term deficit rule with a longer term target for debt. The Government should be open about how large as a percentage of GDP debt should be at some date a few decades from now – say, 2050. This would allow enough flexibility to respond to the short term fluctuation of the business cycle, while ensuring no slippage in the long term.

It would also increase democratic transparency. If other political parties don’t think we need to pay debt down so fast, or believe the Government is being overly cautious in allowing for future recessions, then that is their judgement to make – but it would be better for democratic debate if everyone was more open about what exactly their assumptions were.