It is welcome news that UK Government has dismissed reports that it was considering a scrappage scheme for petrol and diesel cars as a short-term economic stimulus measure. In a typical scrappage scheme, the government would pay car owners to scrap their current vehicle in return for credit against a new one, thereby stimulating the manufacturing sector. However, scrappage schemes are generally not a desirable policy, because they tend to be an inefficient use of public funds, work against the grain of transport decarbonisation, and send mixed price signals alongside Electric Vehicle subsidies.

Despite this, other countries continue to introduce and expand scrappage schemes as economic stimulus measures, and although (we argue) they should be avoided, some schemes are better than others. To make the best of a poor policy, scrappage schemes need to be well-targeted at polluting vehicles and accompanied by complementary policies to tackle the wider market failures facing present-day Electric Vehicles (EV) markets.

The problem with scrappage schemes

A scrappage scheme, if introduced, would not be new to the UK. After the 2008 financial crash, Gordon Brown’s Labour Government introduced a scrappage scheme which involved a subsidy of £2,000 and scrapped 400,000 vehicles in total. Indeed, there were more recent proposals for a new scheme in the 2019 Labour Manifesto. The story behind this scheme is similar to that of Gordon Brown’s scheme: a short-term economic slump threatens the domestic vehicle manufacturing, and a scrappage scheme can act as a short-term stimulus to encourage new vehicle purchases.

In general, scrappage schemes interfere with the market and should be avoided, but in the current crisis Government is reported to be considering one as an economic stimulus. The domestic automobile industry has seen a fall of 89% in new car registrations in May 2020 when compared to May 2019, and could use stimulus measures to keep it afloat. UK car production has been relatively stagnant over the last decade, but remains an important source of employment, with 168,000 people directly employed in domestic vehicle manufacturing, and of exports, with 81% of vehicles produced here exported in 2019.

Despite this, the Government confirming ruling out a scrappage scheme is still good news, due to raise three issues that a scrappage scheme would raise, with the severity of each dependent on the any scheme’s design.

First, the subsidising of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles right now would send highly mixed signals from Government as to the future of transport policy. At present, the UK incentivises Electric Vehicle (EV) purchases through different grants, such as the Plug-in Car Grant, to bring down the higher upfront costs of EVs relative to other vehicles. By subsidising the upfront costs of conventional cars through a scrappage scheme as well as EVs, Government would create mixed and contradictory price signals, potentially deferring investment in EV production.

Second, scrappage schemes are not fiscally efficient. For instance, there is the issue of additionality: many new car purchases bought under a scrappage scheme may have happened anyway, especially if it is only old cars that are eligible which are at the end of their asset life anyway. Whilst this means a scheme could be a good stimulus measure because it creates a short burst of economic activity, it generally does little to generate novel demand in the economy, and could actually dampen longer-term demand for vehicles. That is why scrappage scheme should generally be transparently defined as a short-term stimulus measure, not a long-term subsidy for ICE vehicle manufacturing.

Third, the Government currently has no clear pathway to bringing forward the phase-out date for new ICE vehicle sales to 2035 or earlier. A scrappage scheme introduced to keep domestic ICE vehicle manufacturers afloat, when their current models have an intended shelf life of at most 15 years, is a short-termist view of spending public money if unaccompanied by other, complementary policies.

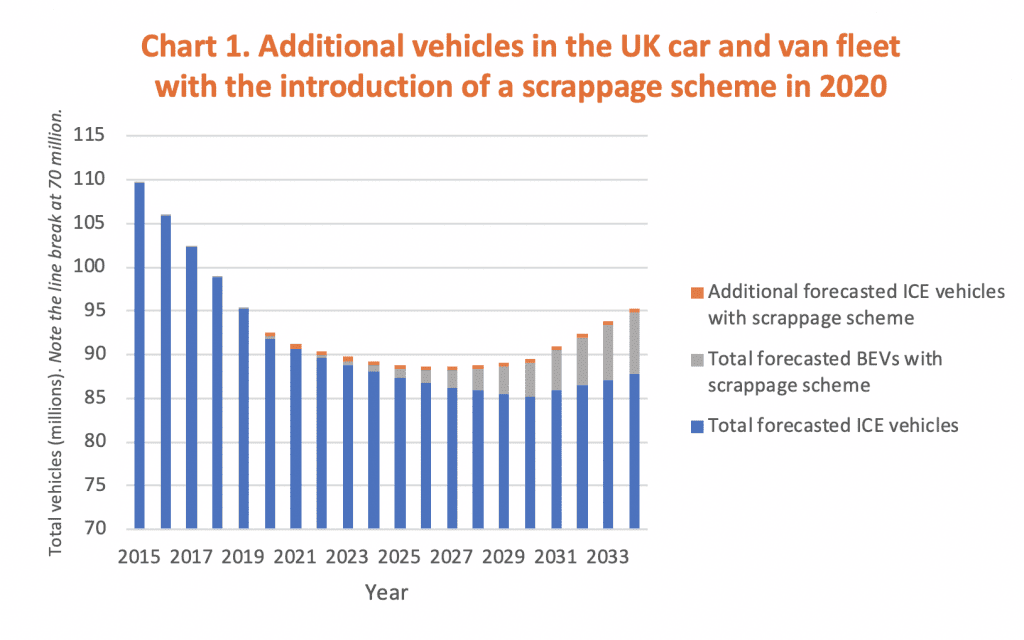

Indeed, if the Government did introduce a scrappage scheme now, it put add additional ICE vehicles on the road, as Chart 1 below indicates. When the industry trade body proposed a scrappage scheme to Government last month, it said a scrappage scheme could add 600,000 vehicles to the road. Assuming 50% of these would be additional vehicles to the regular churn in the fleet, as Transport for London has assumed previously, then 300,000 extra ICE vehicles would be on the road until 2034, with an average life span of roughly 14 years.

Source: Committee on Climate Change (2016), Fifth Carbon Budget Data Set; Policy Exchange analysis.

Chart 1 is indicative only, as there are many factors at play here, such as how much of this additional demand for vehicles from consumers would be ICE vehicles over EVs, and how many scrapped vehicles are truly additional to cars that would have been scrapped anyway.

But the point stands that a scrappage scheme would increase the number of ICE vehicles on the road, making the phase-out of ICE vehicles in time for 2050 – when pretty much all vehicles on the road should be zero emission – harder. It is therefore positive to see Government not taking this route.

Indeed, a UK scrappage scheme would have made achieving the Government’s closer target of a 2035 phase-out date of new ICE vehicles even trickier, because the replacement of 600,000 vehicles now is likely to hamper demand for EVs later. Consumers that would have bought EVs in five years, but chose to scrap their ICE car now, are better off buying a similarly polluting ICE vehicle in 2020 as they are current cheaper than EVs. EVs are projected when to be more competitive later in the 2020s, but cannot compete on purchase price with ICE vehicles in the current market. As such, bringing forward demand for vehicles now would reduce future demand for EVs, as people would be unlikely to buy EVs as replacements and increase emissions from transport in the short term, although by how much is unclear.

All of these issues also only touch on demand-side concerns. The supply chain for EVs, which is currently in its infancy, needs to be matured, and a scrappage scheme would have done nothing to do this by making the phase-out ICE vehicles more difficult in the future.

But scrappage schemes are still popular in other places

Despite the UK Government’s decision not to back a scrappage scheme to boost the economy in the short term, other countries are. France, for instance, has expanded its existing income-based scrappage scheme to allow higher income earners to be eligible. Although scrappage schemes are generally not a good policy tool, there is merit in distinguishing what makes some schemes better than others.

Fundamentally, any scrappage scheme needs to take the most polluting cars off the road, whilst putting cleaner cars on the road. Otherwise, governments that introduce them will have to unpick the effects of current policy in order to meet future decarbonisation targets.

First and foremost, only the most polluting vehicles should be eligible to be scrapped and receive subsidies for doing so, as Policy Exchange has previously recommended. One way to do this is to copy the UK’s 2009 scrappage scheme and only allow vehicles over 10 years old to be scrapped. This would maximise the reduction of negative externalities (emissions and air pollution) for every pound spent, though it also erodes the additionality of the policy (i.e. the cars would have been scrapped soon anyway).

At the same time, vehicles that can be bought as replacements must be at the very least cleaner than those being scrapped. This is to ensure that the vehicles replacing those being scrapped are not more polluting. Ideally, the scrappage scheme would not just require a cleaner replacement to be bought, but the cleanest available. For instance, The Committee on Climate Change has raised the idea that any scrappage scheme should only allow Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) to be bought as replacements for scrapped ICE vehicles.

Notably, this would be hard to introduce within the timeframe of a short-term economic stimulus (around 6-18 months), since the EV supply chain is in its infancy. The current average waiting list for a BEV in the UK is around 12 weeks. On the demand side, consumers would be unlikely to participate in a scheme where they have to forego their mobility for 3 months.

Reducing emissions from transport has already proved a stubborn task, and subsidising people to trade in clunkers for more gas guzzlers would be nonsensical in the context of wider decarbonisation policy.

Any governments seeking to introduce scrappage schemes would also need complementary policies to overcome broader EV market teething problems that a scrappage scheme does not address. An ‘EV Retooling Fund’, for example, would be a good lever to pull in order to support manufacturers (and their parts and maintenance networks) to retrain staff and invest in capital for EV production, particularly to capitalise on the opening up of EV markets in the mid-2020s. Indeed, such a fund could be part of any ‘green recovery’ package without a scrappage scheme, as should be done in the UK to aid industry in the run-up to the 2035 new ICE vehicle sale phase-out date.

But the supply chain is just one challenge that needs addressing if the UK is to maximise the economic benefits of the projected growth in EV markets. The underdevelopment of the charging network, which reduces the convenience of EVs, and the associated range anxiety that undermines confidence among buyers, also need to be addressed by new policies.

It is therefore welcome that the Government is not going to introduce a scrappage scheme, as this would work against existing decarbonisation of transport policy. But foreign Governments still support scrappage schemes of various design, and future UK Governments might be tempted to support one in the future. If schemes are to be made policy, they need to be well targeted with complementary policies to develop the market for EVs. Indeed, policies to do the latter are needed anyway. But without such complementary policies, scrappage schemes effectively prop up domestic industries with an expiry date in an electric future, whilst reducing demand for EVs longer term.