A new Chancellor of the Exchequer and a new Governor of the Bank of England offer the opportunity of taking a fresh look at not just monetary policy, but macro-economic policy as a whole and the role of fiscal policy within it. A decade after the Great Recession, there are profound questions that policy makers should be exploring.

The Bank of England recently hosted a private conference on inflation targeting and published an interesting speech by the Governor, Mark Carney, examining the issues. The outgoing Governor made a point he has made before: that periodic reviews of a central bank’s target, objectives and procedures are beneficial, and that the UK should follow the example of the US, which regularly carries out such reviews.

This exercise would have to be led by HM Treasury, given that it is the Treasury that sets the central bank’s target. The appointment of a new Governor, Andrew Bailey, and a Government with a fresh mandate and a promise to revisit its fiscal framework means it is a good time for a fresh start. It offers an opportune occasion to look again at the work of the central banks, the conduct of monetary policy and the wider coherence of monetary and fiscal policy within macro-economic demand management.

Bringing US-style periodic monetary reviews to the Bank of England

Ten years after economic output started to recover from the Great Recession, central banks have to frame policy in very different circumstances from the previous 40 years. Prices appear to be stable and may be exhibiting a modicum of deflation; interest rates are at their lowest in modern history; previous economic relations that once appeared to hold, such as those relating to employment and wages, no longer prevail. The rates of productivity, capital accumulation and trend economic growth have all slowed. A review of the work of a central bank and the role of monetary policy would have to recognise that monetary policy will not by itself have traction over all of these.

Moreover, the traction that monetary policy would normally have in stimulating economic activity in the short term is much weaker. Monetary policy can no longer be relied on to stimulate the economy in the event of an adverse economic shock. However, a tightening in monetary conditions still bites in slowing economic activity down – that was demonstrated when the Federal Reserve tightened policy in 2018. It has therefore not been an accident that central banks, including the Federal Reserve, have had to row back from that tightening and central bank balance sheets are again expanding. There is an asymmetry in the effect of monetary policy – it cannot stimulate a sluggish economy in a reliable manner, but it can slow down economic activity and avert an inflation spiral. Unfortunately, rising and unstable prices are not our present concern, while having a reliable source of short-term stimulus is.

Mr Carney’s speech recognised the benefits of low and stable inflation. Many monetary policy practitioners have suggested that central banks should be set higher inflation targets to prevent deflation. It is not clear, however, that monetary instruments would be able to deliver such a revised target. Central banks have found it difficult to meet their present targets, while the complex secular influences that have created the present economic environment are unlikely to be easily modified by a monetary approach, however ambitious and adventurous. It would be better to accept the limitations of monetary policy and consider the options for supplementing its role within macro-economic policy with an enhanced active fiscal policy.

Since the Great Recession, Monetary and Fiscal Policy Have Been Fused

An active fiscal policy as part of demand management will be a matter for the Treasury. It would turn on decisions taken about taxes, spending and borrowing – all responsibilities of the finance ministry. Any active fiscal policy should be co-ordinated with the monetary policy that the central bank operates. Policy makers would want to avoid circumstances where monetary policy was in effect vitiating an expansionary fiscal policy. Until 2008, for more than 20 years, economists had thought that fiscal and monetary policy could be neatly separated. Yet during the Great Recession, they effectively became fused. The expansion of central bank balance sheets and the bond purchases at the heart of the unconventional monetary policies were only made possible by taxpayers underwriting the ultimate risks involved. The decisions were inherently political. The combination of very low interest rates and asset purchases had significant distributional implications arising from the significant inflation of asset prices and the collapse in returns for savers.

A monetary policy that coheres with an expansionary fiscal policy would be even more political – it would, in effect, mean the Government taking responsibility for macroeconomic management with the central bank. It would involve new accountability mechanisms to scrutinise policy.

Monetary policy: no more ammunition?

The need for this review of macro-economic management arises from the fact that monetary policy as a reliable source of stimulus has run out of road. This is something which commands a broad consensus amongst economists. As Mr Carney puts it central banks appear to have run out of ammunition. The Bank for International Settlements has shown how the scope for monetary policy has narrowed. Central bank balance sheets have expanded, public debt and debt with negative interest rates has increased and nominal rates have fallen.

Room for monetary policy keeps narrowing

The need to look again at fiscal policy’s role within macro-economic management

There now needs to be a debate about how fiscal policy will be used when economic activity slows and threatens a sustained slump in output. Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, speaking at the annual conference of the American Economic Association this year , called for policymakers to make greater use of fiscal policy in the future. There may be a case for considering whether there is a role for a permanent use of fiscal policy to ensure demand is maintained even the absence of a pronounced shock. Ensuring that monetary policy supports rather than vitiates a necessary stimulus will be important, particularly if an expansionary fiscal policy carried implications for monetary conditions through the exchange rate.

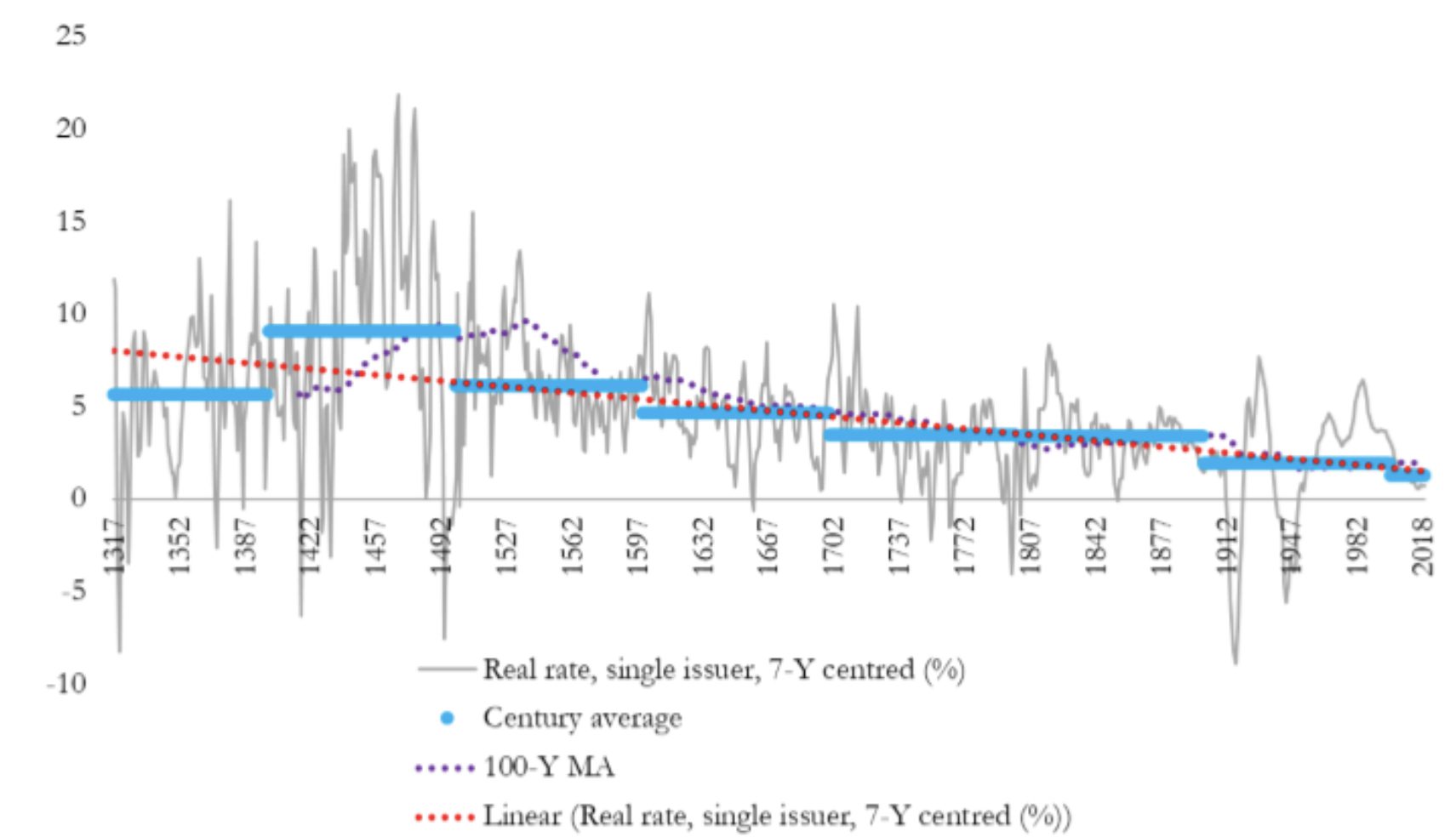

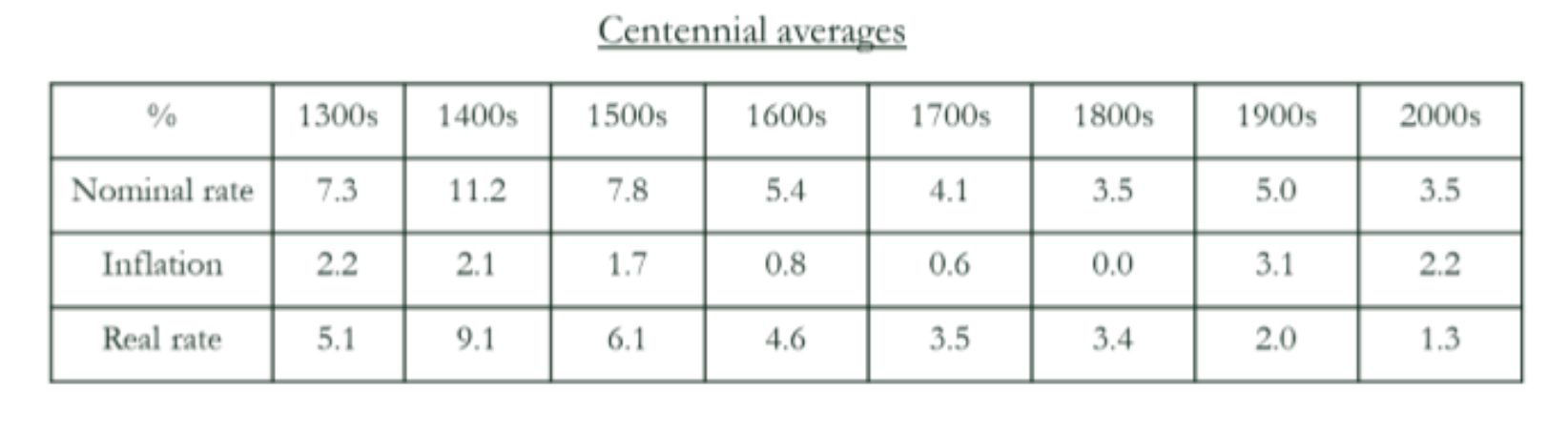

The role of the central bank balance sheet should be considered in relation to the affordability of long-term debt. There are two costs to debt as a policy instrument: firstly, its effect on interest rates and debt service costs, and secondly, the dangers that debt and monetisation of debt present in relation to inflation. In a world of anchored prices, very low nominal interest rates and negative real interest rates, these constraints are much less significant. The extraordinary interest rate position is highlighted in a Bank of England Working paper Eight centuries of global real interest rates, R-G, and the ‘suprasecular’ decline, 1311-2018.

Real long-term safe asset rates and composition by century, 1311-2018

There is now scope to use fiscal policy and public debt as a source of demand stimulus, to finance public investment and to finance current spending of the sort that enhances capital spending and the performance of the economy. Spending on research, training and the services that support the use of new public capital should not be neglected for fear that it may involve borrowing for current spending. In the same way, the state should not refrain from using borrowing, in the present circumstances, to finance reforms to the structure of the tax system to improve incentives and the working of the tax system. The time has come to review not just monetary, but macro-economic policy as a whole and to revaluate the role of fiscal policy within it.

Warwick Lightfoot

February 2020