The Great Recession was the biggest setback that market economies have experienced since the Great Depression and it inevitably continues to have complex economic, social and political consequences. In the first instance policy makers had to stabilise output and wider economic activity as the international economy slumped. In the UK and the US that was broadly accomplished by 2010. It is now 2017, and the challenges are different.

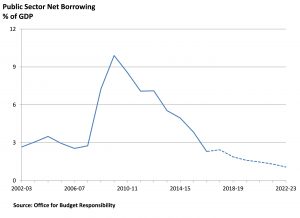

Policy-makers have had to start addressing the consequences of the Great Recession and other structural problems that such a significant shock exposed. In the UK this meant that the high budget deficit and unsustainable structural budget deficit had to be brought down. Among advanced economies the UK was not alone in facing the challenge of deficits and a stock of public debt to GDP that was accumulating too fast and likely to remain uncomfortably high. It soon became clear that this necessary repair of the public finances would take half a generation. In this latest Budget, borrowing continues to fall and for the first time the stock of debt looks as though it is realistically set to peak, stabilise and gradually fall back.

The effect of the Great Recession was to make political life difficult for parties that were blamed for it. Initially it did not stimulate a broader intellectual or political challenge to market economies and the broad consensus on how to manage them that was settled in the 1990s. That began to change with the Occupy movement from 2011 onwards. In the UK since the 2015 election and the emergence of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party a more direct socialistic anti-capitalism has emerged. The UK General Election in 2017 demonstrated that it is a challenge that has to be answered if the case for a market economy is not to be lost by default. Framing that answer is difficult for centre-right politicians because they have not had to mount a cogent defence of a modern economy based on markets, the price mechanism and property rights for over a generation. It is also more challenging because market economies have been through one of their periodic bouts of instability and the combination of technology, trade and increased competition has significantly disrupted labour markets, creating an increased polarisation of employment, income and opportunity.

The effect of the Great Recession was to make political life difficult for parties that were blamed for it. Initially it did not stimulate a broader intellectual or political challenge to market economies and the broad consensus on how to manage them that was settled in the 1990s. That began to change with the Occupy movement from 2011 onwards. In the UK since the 2015 election and the emergence of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party a more direct socialistic anti-capitalism has emerged. The UK General Election in 2017 demonstrated that it is a challenge that has to be answered if the case for a market economy is not to be lost by default. Framing that answer is difficult for centre-right politicians because they have not had to mount a cogent defence of a modern economy based on markets, the price mechanism and property rights for over a generation. It is also more challenging because market economies have been through one of their periodic bouts of instability and the combination of technology, trade and increased competition has significantly disrupted labour markets, creating an increased polarisation of employment, income and opportunity.

The Chancellor’s Triple Challenge

The Chancellor in effect faced a triple challenge in his budget statement. This was to demonstrate further consistent progress in stabilising the public finances and carrying out the fiscal repair job started in 2010; to present a realistic assessment of the economy’s trend rate of growth and evolution of living standards that takes a proper account of the post Great Recession “new normal” world; and to set out a realistic, sober and attractive economic agenda that answers the socialistic critique and remedies of higher spending, taxing and borrowing.

Against that context the Chancellor did well. He spoke with confidence and authority in his statement and set out an attractive, optimistic and robust agenda that placed realism about the public finances at its heart along with an appreciation that future economic opportunity will be a function of technology, innovation and a willingness to adjust to change. It was an agenda that recognises that trade and effective competition policy will play a central role in improving future economic welfare.

Realistic forecasts with scope for a benign surprise

The economic forecast provided by the OBR illustrated the long term character of the post recession fiscal repair. Largely as a result of adjusting for the modest rate of productivity growth the UK economy has exhibited since 2010, the projected trend rate of growth has been cut from around 2 per cent or more to something closer to 1.5 per cent. This is an overdue downward adjustment that better reflects the UK economy’s potential for sustainable expansion. This caution is welcome – indeed it is possible that this projection is now on the pessimistic as opposed to the definitely optimistic side. Given the recovery in the Eurozone, the strength of the US and the OECD as a whole along with the stimulus arising from the lower exchange rate, the actual growth in GDP that takes place may be higher over the coming two years than the forecasts projected in the Red Book.

Slower productivity and forecast economic growth lower projected tax revenue in the medium term. This means that the point when the UK could realistically balance its budget remains further away than implied by the previous official forecast. The important thing is that the UK will continue to make further progress in cutting borrowing and will start to reduce the stock of debt as a ratio of national income. An interesting feature of this financial year’s budget arithmetic is that tax receipts (taking account of some temporary factors) are rising when projected GDP is coming in lower. This suggests that either the relationship between recorded economic activity and tax receipts is less straightforward than it once was, or that GDP is being under-recorded.

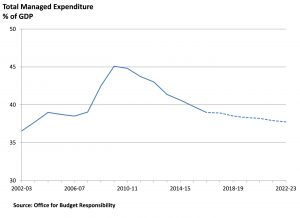

Budgets are inherently political events and the Chancellor astutely judged his rhetoric and his measures. The housing package, assistance for the NHS, easing of the rules surrounding Universal Credit and the further increase in transport and infrastructure funding were the practical response of a finance minister having to operate within a tough budget constraint that will not go away. A slight loosening of 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, some £10 billion in the context of Total Managed Expenditure of over £800 billion and money national income of over £2,000 billion is not profligacy. The important thing is that total managed expenditure as a ratio to GDP is falling to a sustainable and closer approximation of an optimal level.

Budgets are inherently political events and the Chancellor astutely judged his rhetoric and his measures. The housing package, assistance for the NHS, easing of the rules surrounding Universal Credit and the further increase in transport and infrastructure funding were the practical response of a finance minister having to operate within a tough budget constraint that will not go away. A slight loosening of 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, some £10 billion in the context of Total Managed Expenditure of over £800 billion and money national income of over £2,000 billion is not profligacy. The important thing is that total managed expenditure as a ratio to GDP is falling to a sustainable and closer approximation of an optimal level.

The tight fiscal environment meant that the Chancellor had little room for manoeuvre, accepting the aim of reducing the deficit. Within this context, more money was found for certain key policy areas, including housing and productivity. Two other announcements that received less coverage, however, were also very important and deserve highlighting.

Firstly, £3 billion was announced to prepare for leaving the European Union. This is welcome news. A serious and robust approach to scenario planning is what a responsible government should be doing and this will also be useful when negotiating the terms of the UK’s departure from the European Union. Policy Exchange recommended such an approach in its paper, Clean Brexit.

Secondly, the much smaller announcement of an extra £2.8 million per year for Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is important for the performance of the UK economy and enhancing the reputation of capitalism. The CMA will be able to take on more cases against companies that are acting unfairly, and will allow the regulator to use more of the fines it collects to meet the legal costs of defending its decisions. Anti-competitive practices reduce overall economic performance and it is welcome the Government is acting against this.