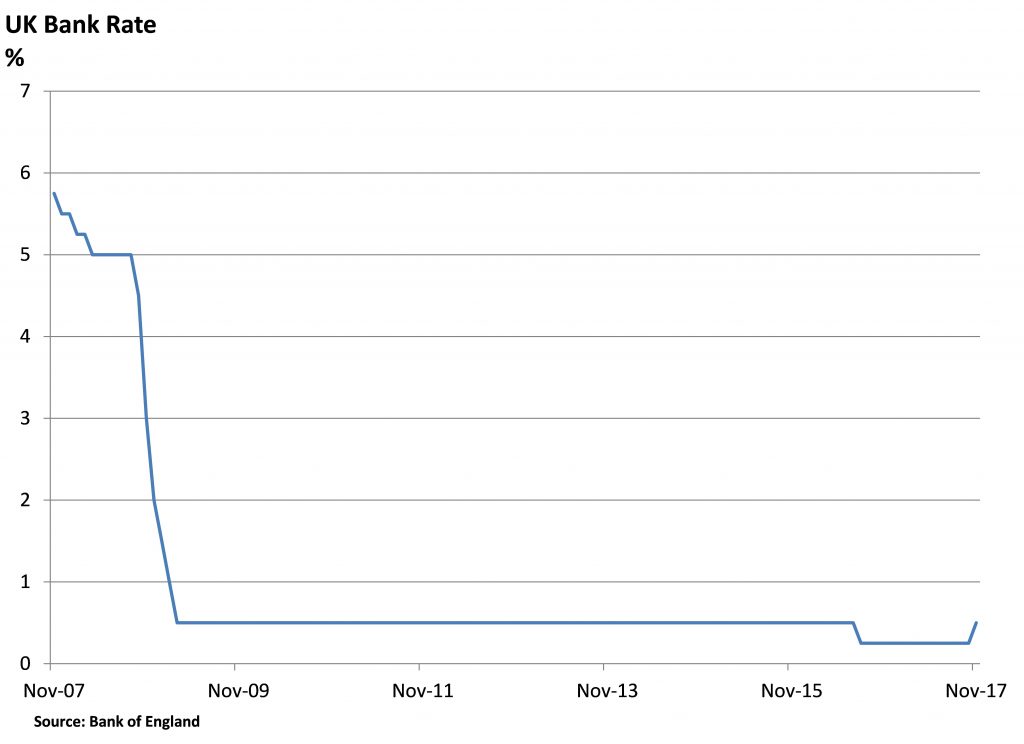

Today’s quarter point rise in interest rates by the Monetary Policy of the Bank of England is notable as the first increase in ten years. But at 0.5% Bank Rate is still at extremely low levels. Indeed today’s move merely reverses last August’s quarter point cut, which was an easing of policy designed to help offset the anticipated slowdown in growth following the EU referendum result. Given that by the end of last year it was clear that the economy was actually in fairly good shape it would have been prudent to have reversed this last rate reduction several months ago. But it is better late than never.

So interest rates are now back at the level they were for the seven years between 2009 and 2016 as the economy gradually recovered from the great recession of 2008/09. This period also included a total of £375bn of asset purchases – or quantitative easing – by the Bank – an amount increased by a further £60bn last August.

Monetary policy remains very loose and supportive of the economy. In particular, bank lending is growing at an annual rate of 6%, suggesting banks are in good shape and willing to meet demand for loans. Inflation is the ultimate target of monetary policy and at present it is above target at 3% in September, having been pushed up by the effect of the sharp fall in sterling on import prices. But as this one-off effect wears off inflation will soon fall back towards the Bank’s 2% target. There are few signs of incipient inflationary pressures, especially in the labour market where wages growth is extremely modest despite an exceptionally low unemployment rate. Meanwhile, there are 17 months to go before the UK is due to leave the European Union and the outlook for GDP growth over this period is extremely difficult to call. Last week’s second quarter growth estimate was encouraging at 0.4% quarter on quarter and the economy is on course for around 1.5% GDP growth this year. (Compare this with Chancellor Osborne’s pre-referendum prediction of a severe slowdown if the UK were to vote to leave the EU.) Falling inflation will soon support real household incomes and boost consumer spending. But heightened uncertainty about the final Brexit situation, especially in relation to trade, may yet result in a slowdown in private sector investment spending as companies await a definitive outcome.

The rise in interest rates today potentially has a strong signalling role – to remind households especially that interest rates can and do go up sometimes. It is estimated that there are around two million mortgage holders for whom this will be the first time that they will have seen an increase in interest rates. The actual increase in mortgage interest payments will be modest and from a relatively low level. Bank officials, including Governor Carney, have repeatedly said that increases in interest rates would be “gradual and limited”. Financial markets are pricing in just two more quarter point rate rises over the next three years. Today the Bank did not repeat previous comments that markets were underestimating the likely extent of future rate rises. This explains why, despite a rate rise, sterling has weakened since the announcement. So while it is not likely to be another 10 years before interest rates rise again, it may be well into the second half of next year before such a move looks likely. Rates steady for now but at a modestly higher level would be our preferred policy stance.

The next major macroeconomic event is the Budget on 22nd November. The MPC will not have anticipated any Budget measures when making its decision today but will incorporate any fiscal policy announcements into its judgement at its next meeting on 14th December.