In August financial markets and economic journalists concentrate on what central bankers say at the Jackson Hole gathering hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas. After Jackson Hole attention will then shift to the Federal Reserve Board’s Open Market Committee Meeting in September. Yet creeping up on the markets is a separate albeit related revival of anxiety about the public debt of the United States of America.

Since Alexander Hamilton transmitted his First Report on Public Credit to Congress at its request the management of government debt has been at the heart of the business of the federal government in the US. As Treasury Secretary Hamilton explained that countries that honour their debts prosper in the same way that people who pay their debts do, bonds issued by the US Treasury Department carrying the full faith and credit of the United States have been among the world’s principal financial benchmarks.

The Full Faith and Credit of the United States and the risk free benchmark

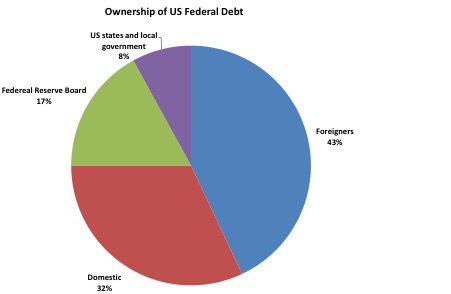

In much financial market analysis and economic theory the Treasury yield curve is the ‘risk free’ bench mark. One of the persistent features of the last thirty-five years has been the status of the dollar as a reserve currency and the willingness of foreign investors to lend to the US Federal Government. It is the willingness of foreign investors to lend the US Treasury money at very low rates of interest that is at the heart of why America is able to finance high and rising levels of public debt and can sustain a persistent structural balance of payments deficit. Confidence in ‘the full faith and credit of the United States of America’ is critical to the dollar’s role as the world’s principal reserve currency.

Debt and War Finance

In the 1980s this facilitated President Reagan’s tax cuts and financing of the rearming of America. President Reagan out spent the USSR in the arms race at the end of the cold war. The episode is analogous to the financial history of the Netherlands and the United Kingdom in the 16th and 18th centuries and their military and political competition with France. Smaller economies were able to mobilise much greater material resources because they had access to debt. The Dutch Republic and Great Britain after the Glorious Revolution in 1688 could borrow because lenders knew they would get their money back. The Bank of England was set up in1694, modelled on Dutch arrangements to manage issues of debt funded by Parliament’s willingness to levy taxes to service the principal and interest payments on that debt. The political contrast with the French Ancien Regime that could not reliably collect tax revenue and pay its debts could not have been greater.

The Risks of Central Bank Monetization of Government Debt

In the First and Second World Wars the same capacity to mobilise financial resources through taxation and debt was present in America and Britain. At the start of the First World War the German Imperial Treasury tried to finance the war through borrowing. The German states collected buoyant sources of revenue from income taxes and the central government had a much less elastic tax base. The Imperial German government expected a short war and had planned for some years to finance such a war through temporary borrowing on the expectation that the cost could be recouped by reparations. That was how Prussia had paid for its war with France in 1870. Little attempt was made to finance the war through higher taxation in contrast to the Allied governments that used taxation and borrowing. Britain had a long record of using income tax as part of war finance form the time of William Pitt. France introduced a progressive income tax in 1914 which was applied for the first time in 1916. The US amended its constitution and introduced an income tax in 1913. Buoyant sources of revenue enabled the Allies to borrow heavily. The contrast with Imperial Germany could not have been greater. Reichsbank was successful in persuading the German public to buy government bonds. After 1916 the public would no longer buy the bonds and the war had to be financed by the central bank directly. The result was the hyperinflation that took place in the Weimar Republic in the early 1920s.

What determines whether a government will pay its way or not?

Whether a government can service its debt turns on two things. The first is the financial and economic capacity that gives it the tax base that can in principle be taxed to pay the debt. In the recent debt crisis Greece plainly did not have an economic base capable of paying is debts. In the 1930s Newfoundland an independent Dominion did not have the taxable capacity to pay its bills and was effectively bankrupted, subject to external commissioners and eventually lost its sovereignty and became a province of Canada in 1949. After 1916 it was not clear to American private bankers that Britain and France would be able to repay debts incurred in the First World War much beyond the debts they had accumulated in the private markets up to the war. And Britain continues to have unpaid debts that it owes the US Government from the First World War.

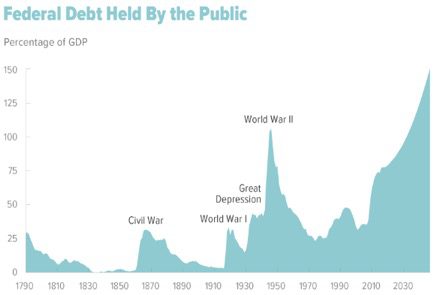

The second is that extent that a state has the political institutions that in practice enable it to tax the economic base that it possesses to meet its debt. In the 18th century France had the economic base to meet its debts but the Ancien Regime did not have the political capacity to tax it effectively. Today it is clear that the US federal government has a rising public debt that it will have to service. It has the economic base that gives it the means to service those debts. The process may involve awkward and uncomfortable decisions about public spending and taxation, but there is little question that it has the economic base and the taxable capacity to pay the bill. Yet there is now a genuine question about the extent that the US federal political system can arrange its affairs to service its debts in a reliable manner without fail.

Over the last thirty years Congress has progressively used the Debt Ceiling as an instrument in partisan politics. Usually a Congress controlled by one party tries to thwart the policies of an administration led by the opposing party. That was the pattern in the 1980s and 1990s and the nub of the rows between the Republican Congress and President Obama. Relations between President Trump and the Republican Congress are so strained that there is a genuine anxiety about whether the Debt Ceiling will be lifted in an orderly manner to allow the federal government to continue to borrow, service debt and carry out government programmes. This will need to be done at some stage before October.

Economic capacity to service debt is one thing, the political will to do so is something else

In 2011 the failure to raise the Debt Ceiling resulted in default on federal debt becoming a potential practicality. It was a very close run thing. The US lost its S&P AAA credit rating much to the irritation of the US Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. Many economists and establishment investors, such as Warren Buffet criticised the S&P rating decision, but it illustrated an important feature of the dysfunctionality of the present federal political institutions. The former director of the Congressional Budget Office Dr Douglas Holtz-Eakin and the former Treasury Secretary, Lawrence Summers, were clear that a default on federal debt even of a technical and temporary character could have devastating consequences for future confidence in US debt and result in higher debt service charges. The General Accountability Office analysis of the episode suggested that it cost the US taxpayer $1.3 billion in 2011 and implied that in future that cost could be over $18 billion. The importance of maintaining investor confidence is especially important now that over 40 per cent of federal debt is held by foreigners (see chart).

The fact that the US government cannot be relied on to agree to raise the $19.8 trillion debt ceiling when both branches of federal government are controlled by the same party illustrates the concern that the S&P credit analysts expressed about the lack of predictability in US institutions and economic policy.