On the 24th June 2016 as the referendum result sank in many analysts scrambled to slash growth forecasts for the UK – both in the immediate and more distant future. A few predicted an immediate plunge into recession as shattered economic confidence took its toll. We have now had fairly complete GDP data for the year following the referendum (to the end of June 2017). Over that period the economy grew by 1.7% which is likely to be close to its trend rate (that is the fastest the economy can grow without generating inflationary pressures). In the year to June 2016 GDP growth was also 1.7%. On this basis one could argue that the referendum made no difference to UK growth prospects whatsoever!

Consumption has slowed as inflation picked up

But of course things did change as sterling immediately fell by around 15% against other major currencies. We are now seeing the effects of this in the real economy – an effect which in many respects is to be welcomed as it represents a rebalancing of the economy. Sterling’s fall has pushed up import prices and contributed to a modest spike in consumer price inflation to 2.6% in July from just 0.6% a year ago. This has squeezed real incomes and brought about a slowdown in consumer spending. In the second half of 2016 consumer spending increased at an annualised rate of 3%, but in the first half of 2017 this has slowed to around 1%. Consumption may continue to go through a soft patch while inflation exceeds wage growth, but a consumer-led recession is highly unlikely.

But inflation will fall back…….

Inflation will fall back after the one-off jump in import prices has dropped out of the annual inflation numbers. It’s a one-off price level adjustment and not the start of a sustained rise in inflation. There are no signs of incipient inflationary pressures – wage growth is modest, commodity prices are moderating and even house price inflation has slowed. Hence inflation will almost certainly fall back over the course of 2018 allowing a return to modest growth in real incomes. This will underpin a modest revival in consumption.

…..and strong employment growth will support consumption

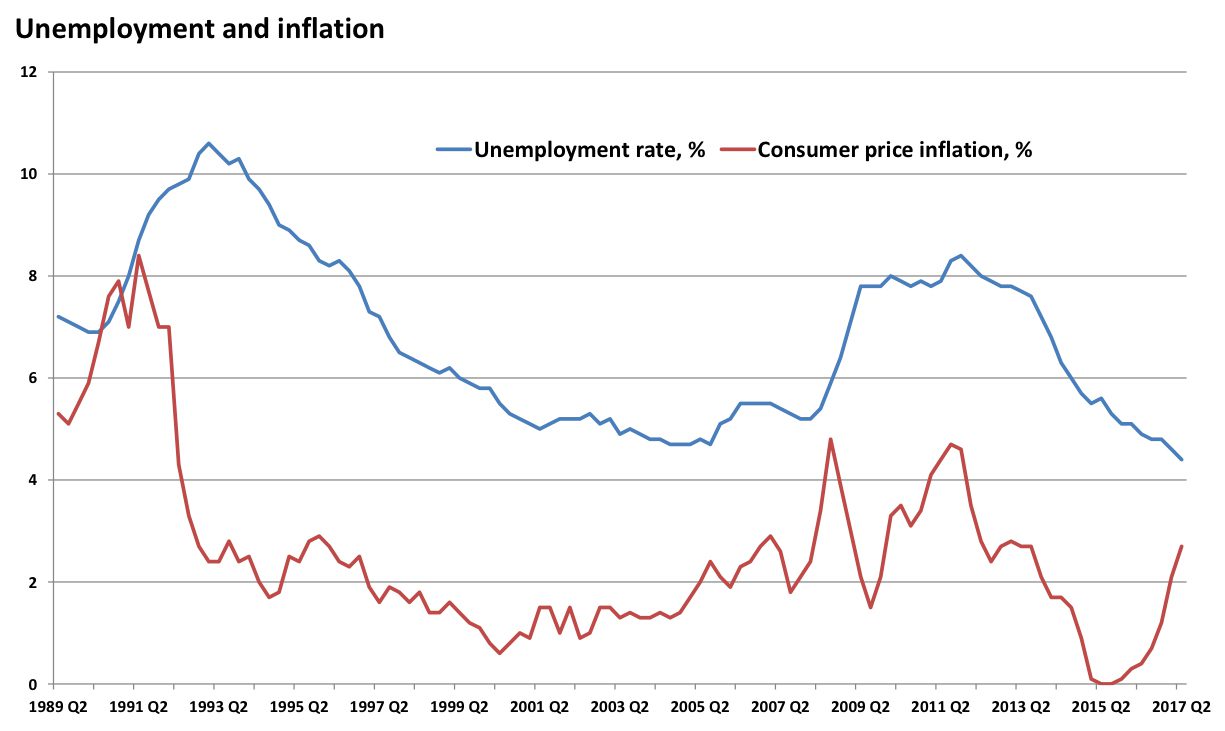

Overall incomes are being supported by employment growth. Over the last year the number of people employed has risen by over 300,000 to a record 32.1 million. Thus while wages are up on average by close to 2% over the last year the measure of labour incomes in the GDP figures is stronger at 3.3%. Employment creation has been almost exclusively in full-time jobs in the private sector. The unemployment rate is now at a 42-year low of just 4.4%. What is even more remarkable is that this level of unemployment co-exists with such moderate growth in wages. The chart below illustrates that the current combination of inflation and unemployment – the so-called misery index – is very low by historical standards.

Sterling’s fall yet to reduce trade deficit

But the positive aspect of a weaker currency and the other leg to rebalancing – an improving trade balance has yet to materialize. Indeed the deficit on goods and services is larger in the second quarter of 2017 than in the same period in 2016. Time lags between changes in the exchange rate and the trade balance are inevitable so it is not surprising that we have yet to see a reduction in the trade deficit. Latest data do show rising goods exports but this is offset by a contraction in services exports. Conditions for a strong export growth are the best for many years, especially to the euro area. Sterling is close to an eight year low against the Euro while at the same time the euro-zone economy is growing strongly, boosted by domestic demand.

The slowdown in consumption and the failure so far of exports to fully respond to weaker sterling has meant GDP growth in the first half of this year at an annualised rate of just 1%. Prospects are for slightly faster growth in the second half of the year as both consumption and exports improve.

Government borrowing under control

The public finances are now in good shape too after seven years of austerity. For the fiscal year 2016-17 public sector borrowing is now just 2.3% of GDP compared with almost 10% of GDP at the peak reached during the Great Recession. So far in 2017-18 the public finances have remained ion track and the latest release showed the first July surplus in 15 years. Buoyant income tax receipts contributed to the £0.2 billion surplus. Slower economic growth may yet prevent a further material decline in the deficit this year but there is no doubt that the public finances are now in a position where they need not be a constraint on macroeconomic policy.

The economy has exceeded many commentators’ expectations in the year since the vote to leave the EU. Potential difficulties will increase as the March 2019 departure date approaches. Certainly the sooner clarity can be established about future trading arrangements with the EU the better. But the economy is going into this period in relatively good shape, albeit more by luck than judgement.